Over 20,000 precious art objects were seized in a raid at dawn — what can this tell us about beauty, theft, and the museum?

On July 4, 2018, Europol and the Italian Carabinieri’s Division for the Protection of Cultural Heritage announced the culmination of “Operation Demetra.” This criminal investigation, tracking a network of Sicilian archaeological looters and international traffickers, resulted in dawn raids on 40 houses in 4 countries and the arrest or detention of 23 people, and the seizure of some 20,000 plundered objects worth an estimated €40 million (approximately $46.6 million).

Art, photography, and unspoken messages

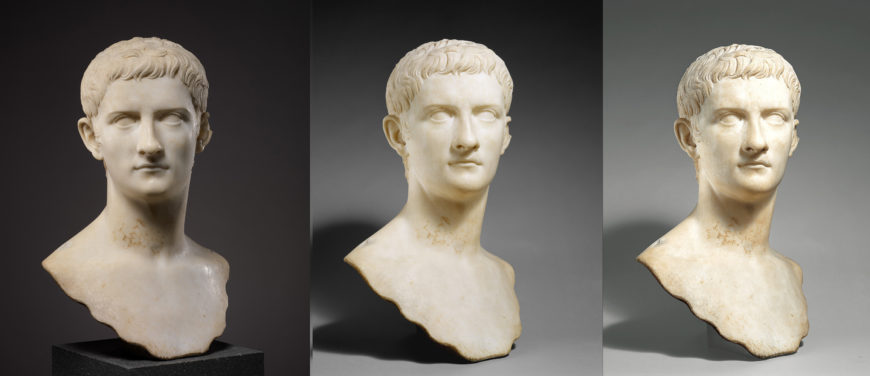

One of the looted works seized in Operation Demetra, probably a 1st century CE portrait of a member of the Roman imperial family, the Julio-Claudians (photo: Europol)

The Europol press release was accompanied by an uncaptioned photograph of a beautiful, naturalistic marble portrait head, presumably one of the works seized in the raids. The portrait depicts a young, beardless man wearing a veil over the back of his head. The figure has a protruding, dimpled chin, and very small ears, but there are few signs of individualization here.

On the basis of its similarity to other works, the portrait can be plausibly identified as a young man of the Roman imperial family from the early 1st century C.E. The sculptor was skilful at capturing in stone the appearance of soft, youthful skin as it stretches over cheekbones and puckers out at the corner of the mouth The nose and left cheek are damaged, but otherwise, the piece seems to be in extraordinarily fine condition. It would be a centerpiece in the ancient gallery of any museum in the world today.

Three museum photographs of a portrait of Caligula, said to have been found near Marino, Lago Albano. Purchased by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1914 from Alfredo Barsanti, Rome (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The head has much in common with other Roman imperial portraits, but the Europol photograph is unique. The depiction is not at all how we’ve become accustomed to seeing ancient sculpture presented. Museum and art market photography usually features pieces like this against a seamless muslin backdrop. The backdrop can be black or gray or, for a little spice, it can fade from black to gray or from dark gray to light. The neutral color, the absence of a horizon line and of any representational detail other than the single object itself, work together to situate the piece in an other-worldly realm, one far removed from any actual specific, physical location. The non-space of these official photographs complements the museum rhetoric of universality. This rhetoric is grounded in a philosophy of art that goes back to Immanuel Kant.

Museums and contexts

Bronze statue identified as Marcus Aurelius, likely one of a large number of bronzes that were looted from an archaeological site in southern Turkey called Bubon in the 1960s and sold to American collectors and museums in subsequent decades (Cleveland Museum of Art)

Implicitly in their architecture and explicitly in their labels, art museums frame their holdings as manifestations of creativity, genius, truth, and beauty — ostensibly universal and timeless human values. This makes the objects’ installation in a museum, often far removed from the particular culture and setting for which they were created and where they may still hold very different meanings, seem unproblematic and even natural.

Sometimes the rhetoric of universality takes on a more literal and pragmatic meaning, as when self-proclaimed “universal museums” claim the right to own — and retain — objects from every corner of the globe, regardless of the dubious circumstances by which they may have acquired them. The two concepts of universality are, of course, mutually reinforcing; and the gray vacuum photographs of record are part and parcel of this ideological apparatus.

Portrait of Drusus purchased by the Cleveland Museum of Art in 2012. It was sold with provenance documents indicating an ownership history going back to the 19th century. These documents turned out to be false; the piece had in fact been stolen from a small museum near Naples in 1944. It was returned to Italy in 2017 (photo: Daderot, CC0)

The Europol press release photo is the antithesis of the gray vacuum images. It is teeming with details that anchor the ancient portrait in a very particular and very mundane realm. The most startling of these details are the two slippers partially visible along the lower edge on either side of the head. These must be the slippered feet of the photographer himself, as he stood over the marble head and aimed his camera at the floor.

The head is lying on what looks like a nice Persian carpet, but our photographer was apparently untroubled by the disarray surrounding it: a pen, whose metal clip catches the light in the image’s upper left corner; two pieces of battered wooden furniture; what appears to be an ornate but broken gilded plaster picture frame; and a blue crocheted blanket. It would not have taken much to push all this detritus out of the frame of the photograph, but our cameraman did not bother. He also apparently couldn’t be bothered, before snapping the picture, to turn off his TV, the blue glow of which illuminates the portrait’s proper right side.

These details not only root the image in a specific earthly setting; they also introduce a concept art world insiders usually take pains to hide from the general public: the inevitably messy human agency behind the removal and relocation of artworks or cultural objects from their original context to their end destination in a gallery display. Europol didn’t release any information about the photograph itself, and it is possible that it was taken by one of the investigators. The slippered feet, however, suggest a different actor, someone in possession of the looted head in his own home.

Erasing stories, erasing the past

We know from other cases of looted antiquities that middlemen often photographed their wares after receiving them from the tombaroli (grave-robbers) who dug them out of the ground. The photographs were used to shop the pieces around to potential buyers. Perhaps this photograph was meant to serve as the basis for negotiations over price between the middleman and the dealer whose role in this network was to smuggle the pieces out of Italy to Munich, where, the investigators claim, they were supplied with false provenance papers and sold at auction. No doubt this laundering entailed new photography as well.

The Europol photograph is a stark reminder that many of those polished marble masterpieces on their spotlit museum pedestals were once merely raw goods on the floor of a crook’s cluttered living room. The alchemy is usually carefully hidden from view; museums do everything they can to keep our attention away from the men behind the curtain.

In its power to reveal more profound truths about museum objects, the Europol photograph recalls the famous image of those manspreading colonialists, the members of the British Punitive Expedition, seated atop their loot at Benin in 1897. That is the “before” image to be paired with the loot’s “after” images, both in photographs of record and in the beautiful modernist grid in the new Sainsbury African Galleries of the British Museum.

The fact that these “before” photographs still have the power to shock years, and even decades, after debates about “decolonizing the museum” have become widespread, and the looting of antiquities is widely recognized as a scourge, reveals how thoroughly we’ve been conditioned by museum rhetoric of beauty and universality. The truth is that the route to the gallery is often ugly, built on crime, brute force, and lies. When we catch a glimpse of that reality, we must not look away.

Gallery devoted to the material from Benin, in the Sainsbury wing of the British Museum (photo: Shadowgate, CC BY 2.0)

This essay first appeared in Hyperallergic (used by permission).

Additional resources:

Peter Watson and Cecilia Todeschini. The Medici Conspiracy: The Illicit Journey of Looted Antiquities – from Italy’s Tomb Raiders to the World’s Greatest Museums (New York: PublicAffairs, 2007).

Europol’s post about Operation Demetra

Read more about Operation Demetra at Artnet

More information about Operation Demetra from ARCA

Read about a campaign to return looted Benin bronzes to Nigeria at Artnet