![Solomon Nunes Carvalho, [View of a Cheyenne village at Big Timbers, in present-day Colorado, with four large teepees standing at the edge of a wooded area. Frame with pemmican or hides hanging at the right; two figures, facing camera, standing to the left of center], between 1853 and 1860, daguerreotype (Library of Congress)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/service-pnp-cph-3c10000-3c10000-3c10000-3c10045v-e1643402092706-870x692.jpeg)

Solomon Nunes Carvalho, [View of a Cheyenne village at Big Timbers, in present-day Colorado, with four large teepees standing at the edge of a wooded area. Frame with pemmican or hides hanging at the right; two figures, facing camera, standing to the left of center], between 1853 and 1860, daguerreotype (Library of Congress)

Incidents of Travel and Adventure in the Far West

Born in Charleston and of Jewish American descent, Carvalho mostly painted portraits and landscapes, but his fame chiefly rests on his work as a photographer. In fact he was the official photographer for an exploratory expedition (led by John C. Frémont) aimed to map a transcontinental railway route between the Mississippi River and the Pacific Coast. Frémont tapped Carvalho for the expedition because of the artist’s successful Daguerreian practice in several cities, among them Philadelphia, Baltimore, and New York. He invented a technical innovation that provided protective coating for daguerreotypes. Hauling cumbersome daguerreotype equipment and other gear, Carvalho traveled through Kansas, Utah, and Colorado, often working in unfavorable weather conditions. This photograph is the only one that survives from a fire in 1881.

Carvalho’s account of the expedition (Incidents of Travel and Adventure in the Far West, 1856), the only record of the trip, was reprinted four times before 1860. The volume discusses both the rigors and discoveries of the journey while also providing Carvalho’s personal reflections, among them his troubles maintaining Jewish dietary laws during the journey. He also described his emotional response to landscape as a connection with God:

After three hours’ hard toil we reached the summit and beheld a panorama of unspeakable sublimity spread out before us. . . . Standing as it were in this vestibule of God’s holy Temple, I forgot I was of this mundane sphere; the divine part of man elevated itself, undisturbed by the influences of the world. I looked from nature, up to nature’s God, more chastened and purified than I ever felt before. [1]

Solomon Nunes Carvalho, Grand River (Colorado River), undated, oil on canvas, 51 x 76 cm (The Oakland Museum Kahn Collection)

Inspired by the vast expanses of land he saw while on the expedition, Carvalho painted landscapes after his return to New York. Composed from sketches made during his travels, Grand River (Colorado River) shows a panoramic view of a river and large canyon capped by an ominous sky. This work was made in the vein of Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Cole. He also painted a dignified yet soulful portrait of Utah Chief Wakara of the Timpanogos tribe, a figure warmly described in Carvalho’s journal. Unfortunately, portraits of other chiefs who sat for Carvalho are lost.

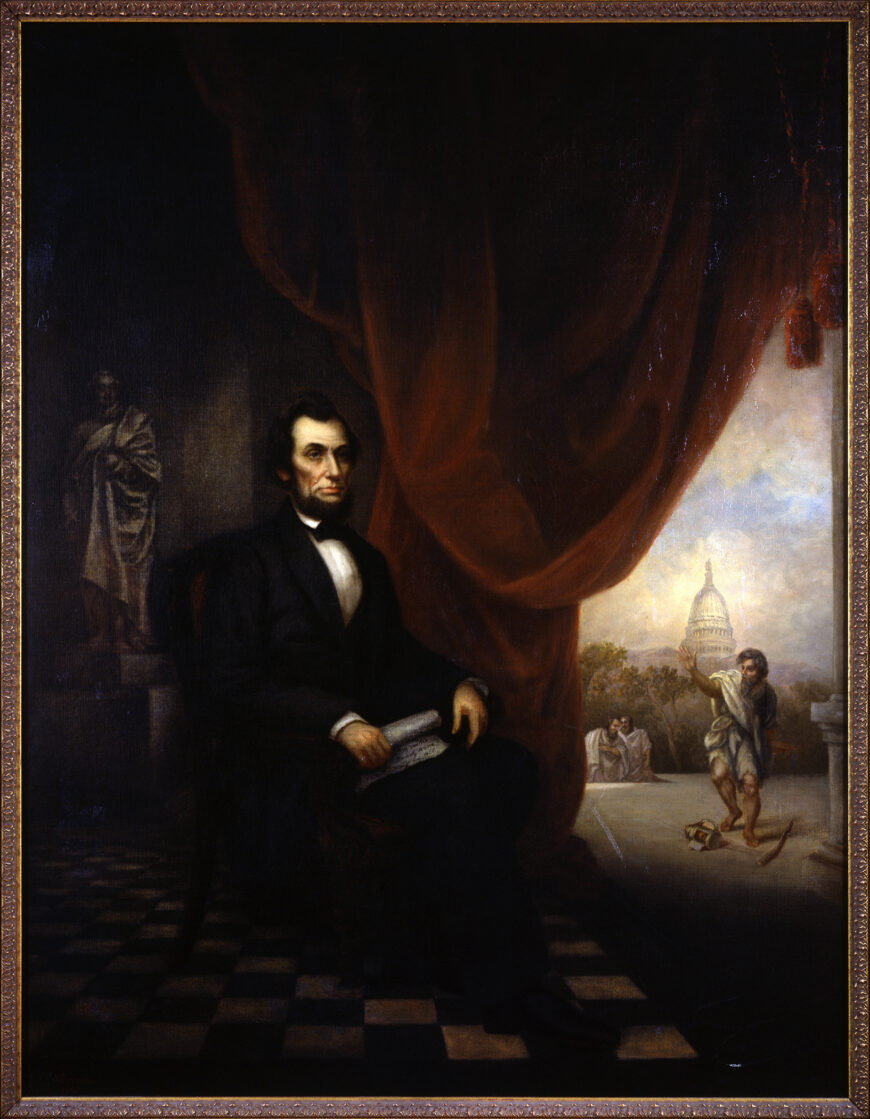

Solomon Nunes Carvalho, Abraham Lincoln and Diogenes, 1865, oil on canvas, 111.76 x 86.36 cm (Rose Art Museum)

Other works

Solomon Nunes Carvalho, Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim, interior, 1838, oil on canvas, 74.9 x 61.6 cm (Collection of Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim)

Still extant are his portraits of members of the Jewish community and some allegorical portraits, including one of Abraham Lincoln (1865). The canvas shows the sixteenth president sitting in front of an open curtain with a scroll in his hand bearing words from his second inaugural address: “With malice toward none, with charity for all.” Behind the curtain appears the Capitol building, a metaphor for the union, and the ancient philosopher Diogenes clad in a toga. Known for his quest through Greece with a lantern in hand to guide his search for an honest man, Diogenes gazes at Lincoln in amazement, lantern dropped at his feet, for he has finally encountered one.

Based on similarities in the artists’ painting style, technique, and subject matter, it has been surmised that the well-known portraitist Thomas Sully trained Carvalho. His earliest known work, a detailed interior of the Beth Elohim synagogue in his hometown of Charleston, was painted from memory because the original structure burned down earlier that year. The silent structure is bathed in sunlight streaming in from two stories of large windows. At twenty-five years old, Carvalho painted Child With Rabbits, a sentimental image of a chubby, angelic boy surrounded by a mother rabbit and her bunnies, which was reproduced on United States currency.

Later life

After the Civil War, Carvalho’s artistic production mostly ceased because of his failing eyesight. Instead, he dedicated his efforts to the betterment of the Jewish community, and business ventures. Indeed, Carvalho was a leader in Jewish affairs, particularly the promotion of Jewish education. In Philadelphia he served as an officer of the Hebrew Education Society, and in Baltimore he was a member of the Hebrew Young Men’s Literary Society. He ran his own business, Carvalho Super-Heating Company, for which he patented heating inventions.

Notes:

[1] Solomon Nunes Carvalho, Incidents of Travel and Adventure in the Far West with Colonel Fremont’s Last Expedition (1856; Reprint, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004), pp. 82–83.

Additional resources

The Art and Life of Solomon Nunes Carvalho from the Princeton University Art Museum.

Solomon Nunes Carvalho: Painter, Photographer, and Prophet in Nineteenth Century America (Baltimore: Jewish Historical Society of Maryland, 1989).

Michael Hoberman, “‘To prove the correctness and authenticity of my statements’: Solomon Nunes Carvalho’s Revision of the Western Travel Narrative,” American Jewish History 102.2 (2018): pp. 237–54.

Bertram Korn, “Some Additional Notes on the Life and Work of Solomon Nunes Carvalho,” The Jewish Quarterly 57 (1967): pp. 360–68.

Robert Shlaer, “An Expeditionary Daguerrotype by Solomon Carvalho,” Daguerrian Annual (1999): pp. 151–159.

Joan Sturhahn, Carvalho, Artist-Photographer-Adventurer-Patriot: Portrait of a Forgotten American (Merrick, NY: Richwood Publishing Company, 1976).