Intentionally buried as part of an elaborate ritual, this ornate object tells us so much, but also too little.

Standard of Ur, c. 2600–2400 B.C.E., 21.59 x 49.5 x 12 cm (British Museum). Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

The Standard of Ur, 2600–2400 B.C.E., shell, limestone, lapis lazuli, and bitumen, 21.59 x 49.53 x 12 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The violence and grandeur of Sumerian kingship

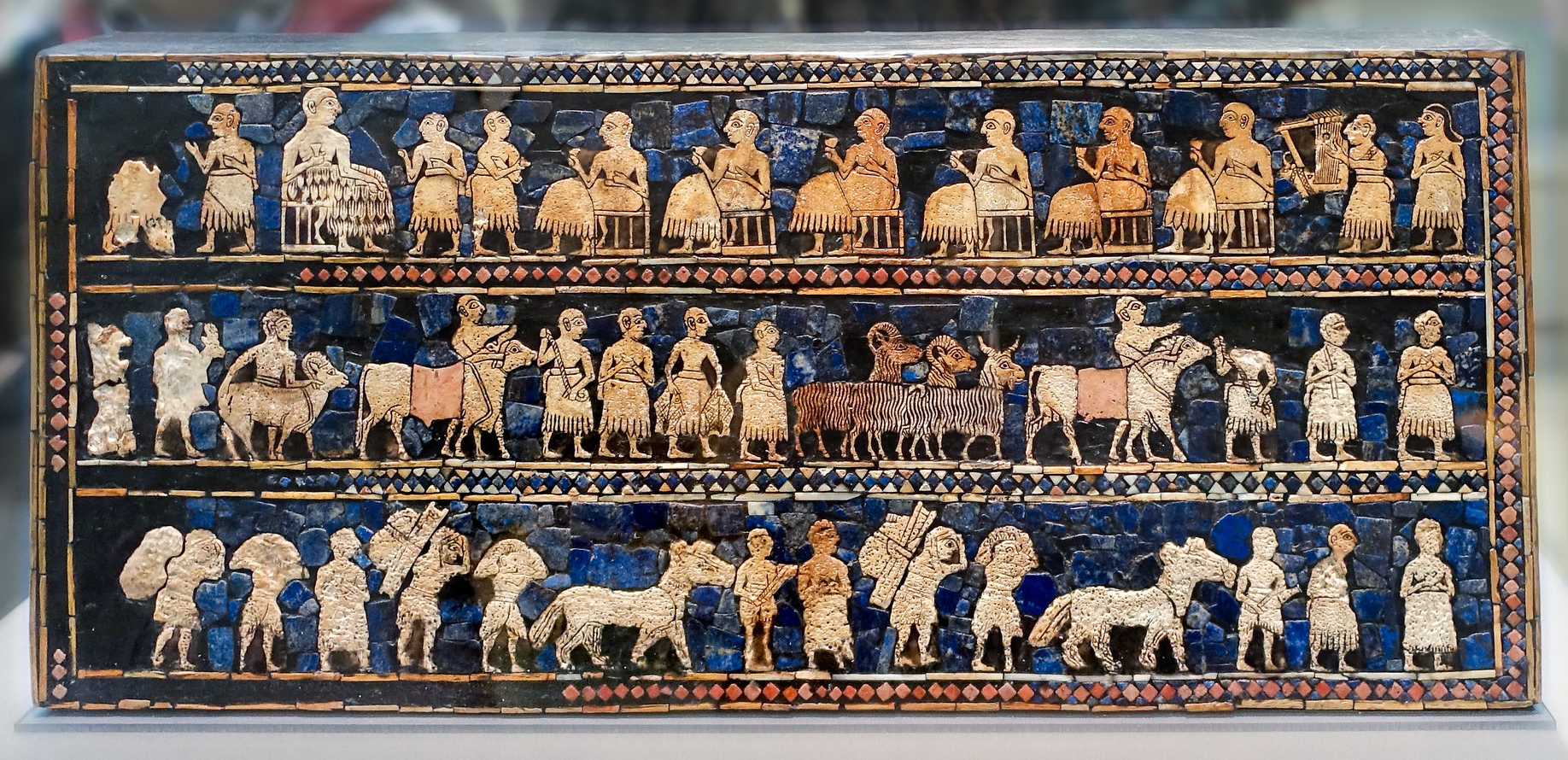

The Standard of Ur is a fascinating rectangular box-like object which, through intricate mosaic scenes, presents the violence and grandeur of Sumerian kingship. It is made up of two long flat panels of wood (and two short sides) and is covered with bitumen (a naturally occurring petroleum substance, essentially tar) in which small pieces of carved shell, red limestone, and lapis lazuli were set. It is thought to be a military standard, something common in battle for thousands of years: a readily visible object held high on a pole in the midst of the combat and paraded in victory to symbolize the army (or individual divisions of the army) of a war lord or general. Although we don’t know if this object ever saw the melee of battle, it certainly witnessed a grisly scene when it was deposited in one of the royal graves at the site of Ur in the mid-3rd millennium B.C.E.

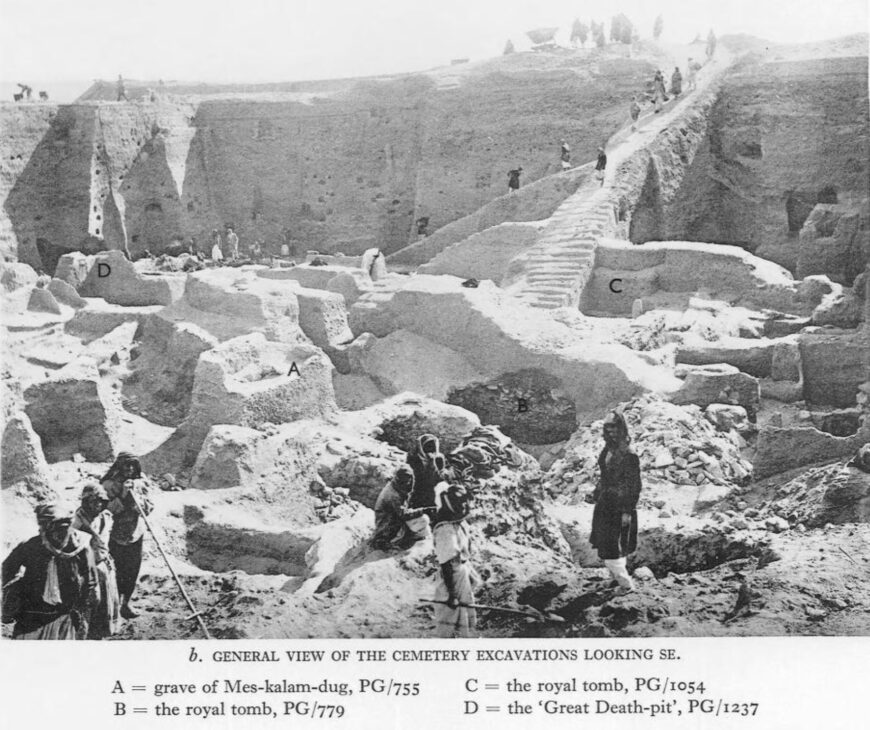

In the 1920s the British archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley worked extensively at Ur and in 1926 he uncovered a huge cemetery of nearly 2,000 burials spread over an area of 70 x 55 m (230 x 180 ft). Most graves were modest, however a group of sixteen were identified by Woolley as royal tombs because of their wealthier grave goods and treatment at interment.

Sir Leonard Woolley, Ur Excavations, volume II, The Royal Cemetery, Plates (British Museum, London and The University Museum, Philadelphia, 1934), plate 8 (available via the Internet Archive)

Each of these tombs contained a chamber of limestone rubble with a vaulted roof of mud bricks. The main burial of the tomb was placed in this chamber and surrounded by treasure (offerings of copper, gold, silver and jewelry of lapis lazuli, carnelian, agate, and shell). The main burial was also accompanied by several other bodies in the tomb, a mass grave outside the chamber, often called the Death Pit. We assume that all these individuals were sacrificed at the time of the main burial in a horrific scene of deference.

Queen’s Lyre (reconstruction), 2600 B.C.E., wooden parts, pegs and string are modern; lapis lazuli, shell and red limestone mosaic decoration, set in bitumen (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

One of the royal graves (PG779) had four chambers but no death pit. It had been plundered in antiquity but one room was largely untouched and had the remains of at least four individuals. In the corner of this room the remains of the Standard of Ur were found. One of its long sides was found lying face down in the soil with the other one face up, which lead Woolley to conclude that it was a hollow structure; additional inlay were found on either side of the short ends and appeared to fill a triangular shape and which lead to the Standard being reconstructed with its sloping sides. The remains of the Standard were found above the right shoulder of a man whom Woolley thought had carried it attached to a pole. The identification of this object as a military standard is by no means secure; the hollow shape could just as easily have been the sound box of a stringed instrument, such as the Queen’s Lyre found in an adjacent tomb.

War and peace

The two sides of the Standard appear to be the two poles of Sumerian kingship, war and peace. The war side was found face up and is divided into three registers (bands), read from the bottom up, left to right. The story begins at the bottom with war carts, each with a spearman and driver, drawn by donkeys trampling fallen enemies, distinguished by their nudity and wounds, which drip with blood. The middle band shows a group of soldiers wearing fur cloaks and carrying spears walking to the right while bound, naked enemies are executed and paraded to the top band where more are killed.

War (detail), The Standard of Ur, 2600–2400 B.C.E., shell, red limestone, lapis lazuli, and bitumen (original wood no longer exists), 21.59 x 49.53 x 12 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In the center of the top register, we find the king, holding a long spear, physically larger than everyone else, so much so, his head breaks the frame of the scene. Behind him are attendants carrying spears and battle axes and his royal war cart ready for him to jump in. There is a sense of a triumphal moment on the battlefield, when the enemy is vanquished and the victorious king is relishing his win. There is no reason to believe that this is a particular battle or king as there is nothing which identifies it as such; we think it is more of a generic image of a critically important aspect of Ancient Near Eastern kingship.

Peace (detail), The Standard of Ur, 2600–2400 B.C.E., shell, red limestone, lapis lazuli, and bitumen (original wood no longer exists), 21.59 x 49.53 x 12 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The opposite peace panel also illustrates a cumulative moment, that of the celebration of the king, this time for great agricultural abundance which is afforded by peace. Again, beginning at the bottom left, we see men carrying produce on their shoulders and in bags and leading donkeys. In the central band, men lead bulls, sheep and goats, and carry fish. In the top register a grand feast is taking place, complete with comfortable seating and musical accompaniment.

On the left, the largest figure, the king, is seated wearing a richly flounce fur skirt, again so large, even seated, he breaks the frame. Was it an epic tale of battle that the singer on the far right is performing for entertainment as he plays a bull’s head lyre, again, like the Queen’s Lyre? We will never know but certainly such powerful images of Sumerian kingship tell us that whomever ended his life with the Standard of Ur on his shoulder was willing to give his life in a ritual of kingly burial.

Additional resources

This work at the British Museum

Ur and its Treasures: The Royal Tombs (Penn Museum)

Dorota Ławecka, “Who were the Tribute-Bearing People on the ‘Standard of Ur’?,” Journal of Near Eastern Studies, volume 76, number 2 (2017).

Joan Aruz, editor, Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2003).

Sarah Collins, The Standard of Ur (London: British Museum Press, 2015).

Dominique Collon, Ancient Near Eastern Art (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995).

Harriet Crawford, Sumer and Sumerians (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2004).

Nicholas Postgate, Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the Dawn of History (London: Routledge, 1994).

Michael Roaf, The Cultural Atlas of Mesopotamia and the Ancient Near East (New York: Facts on File, 1990).

Leonard Woolley and P.R.S. Moorey, Ur of the Chaldees, revised edition (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1982).

Norman Yoffee, Myths of the Archaic State: Evolution of the Earliest Cities, States, and Civilization (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

Richard L. Zettler and Lee Horne, editors, Treasures from the Royal Tomb at Ur (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1998).

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”standard of ur,”]

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:04] On the back of a US dollar bill, there’s an emblem of an eagle. In its talons you have arrows, the symbol of war. But on the other side, you have an olive branch, a symbol of peace.

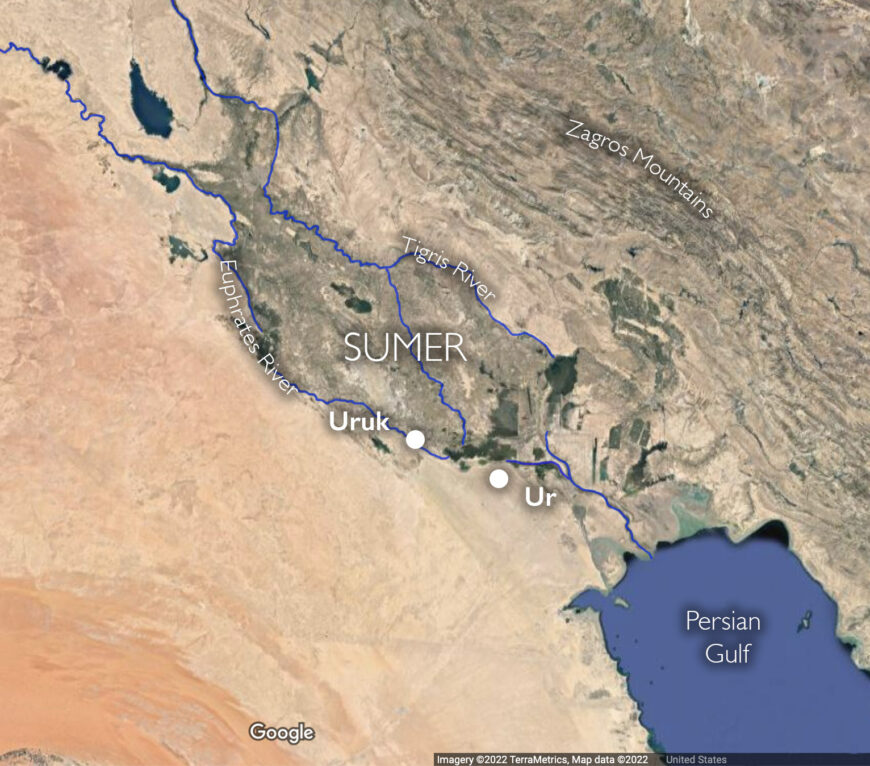

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:16] That’s not so different than this object that we’re looking at that’s nearly 4,500 years old, an object known as the “Standard of Ur,” which comes from the city-state of Ur, which is present-day Iraq.

Dr. Zucker: [0:27] Ur is one of the early cities in Mesopotamia, the birthplace of civilization. The word “standard” is a little misleading, because a standard is really a flag that’s often brought into battle, and the original excavator of this hypothesized that perhaps this was on a pole originally and was brought into battle, but in truth, we have no idea.

Dr. Harris: [0:46] Here, we’re looking at objects that were part of what seems to have been an elaborate burial ritual. These were excavated in the ’20s and the early ’30s by a man named Leonard Woolley, who discovered about 16 tombs that he called royal tombs.

Dr. Zucker: [1:02] Again, we don’t know, but what we do know is we see fabulously expensive objects.

Dr. Harris: [1:07] One of those valuable objects was the object we call today the Standard of Ur, which is small but elaborately decorated.

Dr. Zucker: [1:15] Historians have thought that perhaps this is a sound box for a musical instrument. Others have thought it might have contained something important, perhaps even the currency that was used to pay for warfare.

Dr. Harris: [1:24] One of the wonderful things about this object is that it tells us so much. And at the same time, it tells us so little.

Dr. Zucker: [1:31] This object is small enough so that it could easily be carried.

Dr. Harris: [1:34] One long side seems to represent a scene of peace and prosperity.

Dr. Zucker: [1:38] It’s divided into three registers, and it’s framed with beautiful pieces of shell. Now, this is important, because it really does show us the long-distance trade that this culture was involved with.

[1:47] You’ve got blue — lapis lazuli that came from mines in Afghanistan. You have a red stone that would have come from India. You’ve got shells, which would have come from the gulf just to the south of what is now Iraq. It reminds us that these first great cities were possible because agriculture had been successful.

[2:02] In the river valley between the Tigris and the Euphrates, it was possible to grow a surplus of food that allowed for an organization of society where not everybody had to be in the fields all the time. Once there was enough food, some people could devote their lives to being rulers, and some to becoming artists or artisans.

Dr. Harris: [2:20] And some to [becoming] priests. You had a whole organization of society with different people performing different roles that was suddenly possible.

Dr. Zucker: [2:27] You can see that organization represented in the three registers. The wealthiest, most powerful figures are towards the top. Then the common laborers down at the bottom.

Dr. Harris: [2:36] It’s typical for us to see scenes divided into registers.

Dr. Zucker: [2:40] Let’s start down at the bottom and move up. I see a human figure bearing a heavy bag.

Dr. Harris: [2:45] That’s what we have along the entire bottom register. We see animals, figures carrying things across their shoulders or on their backs.

Dr. Zucker: [2:53] Just above that, you can see a number of people leading more clearly identifiable animals. You can see somebody herding along what looks like a sheep or a ram. You see a bull in front of that, being led by two people. Then perhaps goats, perhaps sheep ahead of that and another bull. These are people that might be bringing these animals to sacrifice.

[3:11] They might be bringing them as taxation. People have hypothesized that this is showing a collection perhaps for the king, for the city. The register at the top shows one figure that’s more important than the rest. The king is larger. In fact, so large that his head breaks into the pictorial frame.

Dr. Harris: [3:28] He also wears different clothing that helps to identify him.

Dr. Zucker: [3:31] He’s seated on a chair that’s got three straight legs and one leg that seems to be the leg of an animal.

Dr. Harris: [3:38] Some of the objects that we see here are objects that were also found in the burials. But I don’t think they found a chair that resembles that.

Dr. Zucker: [3:46] One of the objects that has been found, however, are the cups that so many of the figures are holding. These figures are joining the king in some libation.

Dr. Harris: [3:55] There’s some kind of celebration going on, perhaps a religious ceremony.

Dr. Zucker: [3:59] The figures who are seated but are not the king are larger than the servants that surround them that are standing. Even within the register, you have a hierarchy that shows the relative importance of three levels of society.

Dr. Harris: [4:12] Then we have two figures at the far end who seem to be entertaining the seated figures who are drinking. One is playing a harp, and another figure on the far right [is] perhaps singing.

Dr. Zucker: [4:23] Let’s go to the other side. It’s a very different story.

Dr. Harris: [4:25] Again, we have a scene divided into three registers. But here we see scenes of violence.

Dr. Zucker: [4:31] We see a rendering of warfare. There are four chariots that are pulled by what seem to be four male donkeys. On the back of each chariot seem to be a driver as well as a warrior. The figure towards the rear is holding either a spear or an axe. Then, being trampled by the donkeys, are the enemy.

Dr. Harris: [4:51] There are more spears in the chariots.

Dr. Zucker: [4:53] Look at one of the men that has been felled under the donkey. You can see his wounds. You can see blood flowing. If you look closely, you can notice the mechanism of the wheels of the chariots. There’s a specific engineering that’s being rendered here.

Dr. Harris: [5:08] One of the most interesting things about the bottom panel is a kind of naturalism in the battle taking place.

Dr. Zucker: [5:14] You seem to move from a walk to a canter to a full gallop.

Dr. Harris: [5:17] On the other hand, some elements are symbolic, like the felled enemies. I don’t think we’re meant to assume that there were four people who died in this battle. That’s symbolic of many more.

Dr. Zucker: [5:28] The middle register shows a line of soldiers readied for battle. They are in full garb. They’re wearing helmets. These helmets have, again, been found in the so-called royal tombs.

Dr. Harris: [5:39] What’s wonderful about these soldiers is their regular placement gives you a sense of an army that’s marching along.

Dr. Zucker: [5:45] You get a sense of order. You get a sense of structure. You get a sense of real discipline. Towards the middle of that register, you see the battle taking place. You see these soldiers victorious, slaying their enemies. On the right side of that middle register, you see soldiers that are perhaps being captured.

Dr. Harris: [6:00] Our eye, in the top register, goes immediately to the large figure at the center, which is the king. His head again breaks the decorative border along the top; on the left, a chariot and soldiers, and on the right, other soldiers or attendants bringing to the king prisoners of war.

[6:19] We can tell that these are prisoners of war because they’re naked. They’ve been stripped. And they’re wounded and bleeding.

Dr. Zucker: [6:25] There’s a sense of their humiliation, their enslavement, and the victory of the king. It’s interesting to look closely at the stylistic conventions of the rendering of the figures.

[6:36] Just about everybody is seen in perfect profile. We see one eye, not so much looking forward as looking out in a way that is familiar from Egyptian art. We see the shoulders squared with the picture plane. We see feet pushing in one direction rather than being seen in perspective.

Dr. Harris: [6:53] We can use our visual detective work, but there’s still so much that’s a mystery.

Dr. Zucker: [6:58] What it does tell us is that the way that we tell a story over time, the way that we organize our society even now in the 21st century, has a lot in common with the third millennium B.C.E.

[7:09] [music]