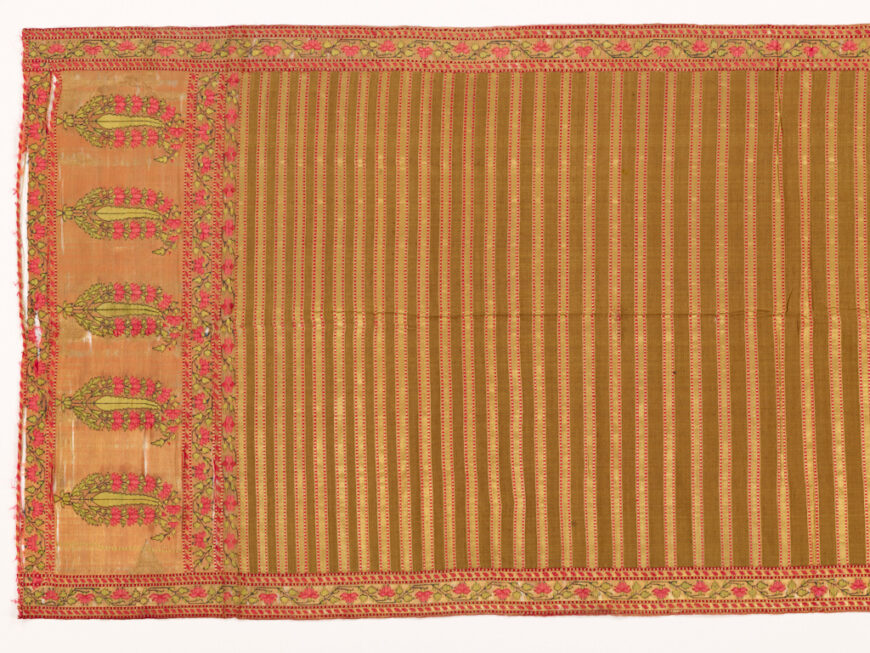

Floral and paisley designs (detail), Patka (man’s sash), 1750–1800 (Mughal empire, India), silk, metallic-wrapped thread, 322.6 cm long (Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence)

The community-based production of handcrafted textiles across the Indian subcontinent has fostered generations-long engagement with techniques and materials that are rooted in the ancient caste system, a hierarchical social order that accords communities with specific jatis or castes based on their traditional occupations. This system enforced strict demarcations, confining people to their designated social groups, professions, and status.

Over the years, the centuries-old caste-based division of labor has continued to underpin the formal arrangements of textile practices that emerged as a response to increasing commercial demands, overseas trade, and royal patronage. We see this most prominently in the 16th and 17th centuries when establishments such as karkhanas or imperial workshops and weavers’ associations reorganized prevailing systems of textile production, granting groups of artisans better access to raw materials, new technologies, and, ultimately, greater economic and social mobility. In this topic, we explore two examples that emerged simultaneously in different parts of the subcontinent.

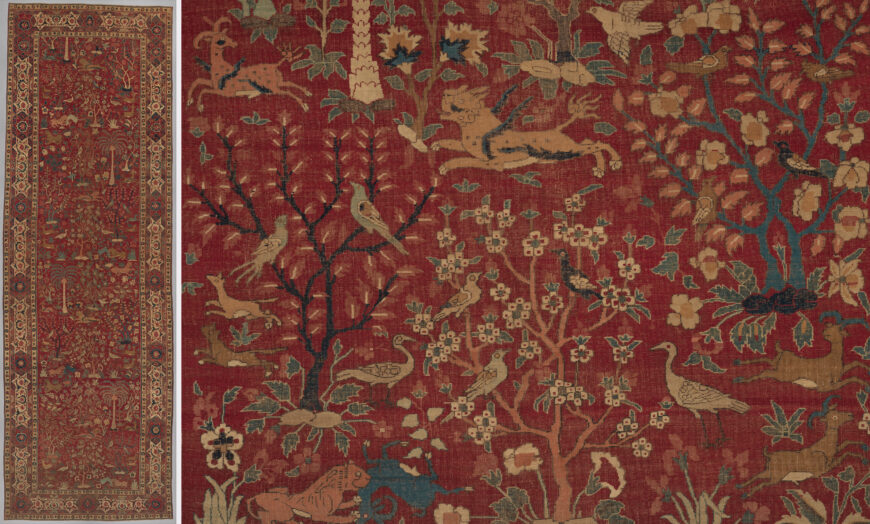

Full carpet (left) and hunting scenes (detail, right). Carpet with Palm Trees, Ibexes, and Birds, late 16th–early 17th century (Mughal empire, Lahore, present-day Pakistan), cotton, wool, 833.1 x 274.3 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Safavid carpet with similar hunting scenes. The Emperor’s Carpet, second half 16th century (attributed to Iran), Safavid empire, silk and wool, 759.5 x 339.1 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Mughal karkhanas: cross-cultural interactions

While karkhanas were operating in the Indian subcontinent since the 13th-century Tughlaq dynasty, textile production in these workshops became especially popular during the time of the Mughal emperor, Akbar, in the 16th century. Akbar set up karkhanas in Lahore, Agra, and Ahmedabad, which hosted entire communities of weavers, embroiderers, dyers, and printers who produced textiles exclusively for the needs of nobility as well as for trade. In these workshops, artisans were provided with the tools, equipment, raw materials, and capital to produce exquisite silks, Pashminas, and muslins, among other textiles. Master weavers were invited from other regions, especially Safavid Iran, to train these local artisans in specialized techniques such as brocade and carpet weaving. The karkhanas effectively served as spaces that encouraged the exchange of ideas and technical practices among artisans of diverse backgrounds. These interactions led to valuable innovations and prominent cross-cultural influences that reflected in the making and the appearance of the textiles. Brocade and carpet designs produced by the Mughals, for instance, were aesthetically similar to Safavid textiles depicting Persianate motifs, such as hunting scenes (shikargah), scrolling vines, and other floral designs. These textiles became so popular within and outside the subcontinent that textiles soon became the most valued commodities in the karkhana system—which also produced a range of craft items, manuscripts, and paintings—and one of the most important sources of revenue for Mughal rulers.

Left: Kailasanathar Temple, Kanchipuram, Tamil Nadu, India (photo: balaji shankar venkatachari, CC BY-NC 2.0); right: detail of sari with temple border motifs, late 20th–early 21st century (Chettinad, Tamil Nadu, India), cotton, 462 x 114 cm (Museum of Art and Photography, Bengaluru)

Weavers’ associations: hubs of urban development

Around the same time, southern India saw the emergence of a very different system of work for textile artisans. Here, the Vijayanagara, Chola, and Nayaka rulers encouraged several communities of weavers to migrate to the newly built towns in their kingdoms, offering them patronage and residential spaces to live and work. These migrant weaver communities settled around important temples, which eventually formed the locus of the town’s cultural and social life. As a result, the history of these South Indian towns is intricately linked to the emergence of weavers’ associations. These groups loosely resembled workers’ guilds, controlling the production and trade of certain crafts and representing the political, social, and economic interests of their members in courts and markets. Weavers’ associations functioned in similar ways, providing raw material, training, and financial assistance to weaving communities. In addition to producing textiles for their royal patrons, they were also commissioned by priests to weave for temple deities, a task that granted them upward social mobility.

Left: detail of sari with Rudraksh motif along borders, late 20th century–early 21st century (Kanchipuram, Tamil Nadu, India), silk, gilt metal (Museum of Art and Photography, Bengaluru); right: Yali motif (detail), textile fragment, 15th–16th century (India), silk, samite, 29.3 x 17.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Their proximity to the temples further inspired them to incorporate decorative elements from temple architecture into their textiles, including motifs such as Yali, Rudraksh, and temple borders. Furthermore, these associations facilitated networks of communication between master weavers and merchants, allowing textile artisans to participate directly in domestic and overseas trade. Over time, these associations contributed to the transformation of these towns from religious centers into hubs of commerce, trade, and urban life.

Man’s Morning Coat, 1700–50 (Mughal empire, India, for French market) cotton, gold leaf, 142 x 172 cm (The Cleveland Museum of Art)

Factors such as migration, patronage, and trade have influenced many forms of existing, caste-based textile practices across the Indian subcontinent. In addition to the literal reorganization of labor, these influences can also be evidenced by cross-cultural confluences in technology, technique, and design vocabulary. Contemporary systems of work in the subcontinent have evolved across generations, with aspects of their structures and pedagogical setups dating back centuries. While the intergenerational nature of such community-based textile production has encouraged distinct relationships between makers and their practices and has kept age-old traditions alive, its ties to the caste system have also resulted in the severe economic and social marginalization of certain textile communities that have been deemed “lower caste.”

Discrimination on the basis of caste was legally abolished in India in 1950, and newer generations of some textile communities have begun to move away from their inherited occupations in pursuit of better opportunities. Despite the legal measures taken to safeguard the rights of marginalized groups, however, the caste system continues to be prevalent in the subcontinent, impacting the economic and social lives of several communities. Regardless, textile artisans also remain preservers of ancient traditions and practices, with many taking pride in the inimitability, complexity, and uniqueness of their work.

Additional resources

Take a short course on Textiles from the Indian Subcontinent with The MAP Academy

R. Champakalakshmi, “Growth of Urban Centers in South India: Kudamukkupalaiyarai, The Twin City of the Cholas,” Proceeding of the Indian History Congress, volume 39 (1978), pp. 168–79.

Katie Currie, “The development of petty commodity production in Mughal India,” Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars, volume 14, number 1 (1982), pp. 16–24.

Boni Dutta, “An Insight into the different types of Mughal Karkhanas,” Journal of Emerging Technologies and Innovative Research, volume 5, number 7 (2018), pp. 1178–80.

Richard A. Frasca, “Weavers in Pre-Modern South India,” Economic and Political Weekly, volume 10, number 30 (1975), pp. 1119–23.

Irfan Habib, “Potentialities of Capitalistic Development in the Economy of Mughal India,” The Journal of Economic History, volume 29, number 1 (1969), pp. 32–78.

Vijaya Ramaswamy, “Silk and Weavers of Silk in Medieval Peninsular India,” The Medieval History Journal, volume 17, number 1 (2014), pp. 145–69.

Vijaya Ramaswamy, Textiles and Weavers in Medieval South India (Dehli: Oxford University Press, 2016).

Vijaya Ramaswamy, “Migration of the Weaver Communities in Medieval Peninsular India, Thirteenth to the Eighteenth Century,” Migration in Medieval and Early Colonial India (New York: Routledge, 2016).

Albert James Saunders, “The Saurashtra Community in Madurai, South India,” The American Journal of Sociology, volume 32, number 5 (1927), pp. 787–99.

Drawing from articles on The MAP Academy