Italian renaissance art: an introduction

Read Now >Chapter 48

Art in Sovereign States of the Italian Renaissance, c. 1400–1600

All that Glitters . . .

As Uncle Ben so succinctly put it to a young Peter Parker (AKA Spiderman), with great power comes great responsibility. Perhaps because no renaissance rulers enjoyed the superhuman talents awarded to Spiderman, they had to use other means to communicate their suitability for the job. The objects and buildings a prince and his family patronized were reflections of their taste and learning, their dignity and their magnificence. Visual art helped a prince self-fashion as an ideal and rightful ruler.

Francesco del Cossa, Cosme Tura, and Ercole de’ Roberti, detail of Duke Borso and court, 1469–70, Salone dei Mesi, Palazzo Schifanoia, Ferrara, Italy (photo: Sailko, CC BY-SA 3.0)

In 1472, Borso d’Este, Lord of Ferrara, was described by a courtier as:

lordly and resplendent with his imperial appearance ornamented by gold and gems. . . . [1]

Such glittering descriptors were common of renaissance rulers—they shined, they sparkled, they gleamed, they were even addressed in letters as illustrissimus (bright, shining, brilliant). Like the sun, the renaissance prince (a common term for a renaissance ruler) illuminated his territory with the glamor of his magnificence, his authority communicated by the brilliance of his person. This brilliance was both literal—princes donned luminous fabrics, gleaming swords, and lustrous gems—and metaphorical. Noble comportment, exemplary piety, and even the patronage of art and architecture reflected the brilliance of the prince, and confirmed his right to rule.

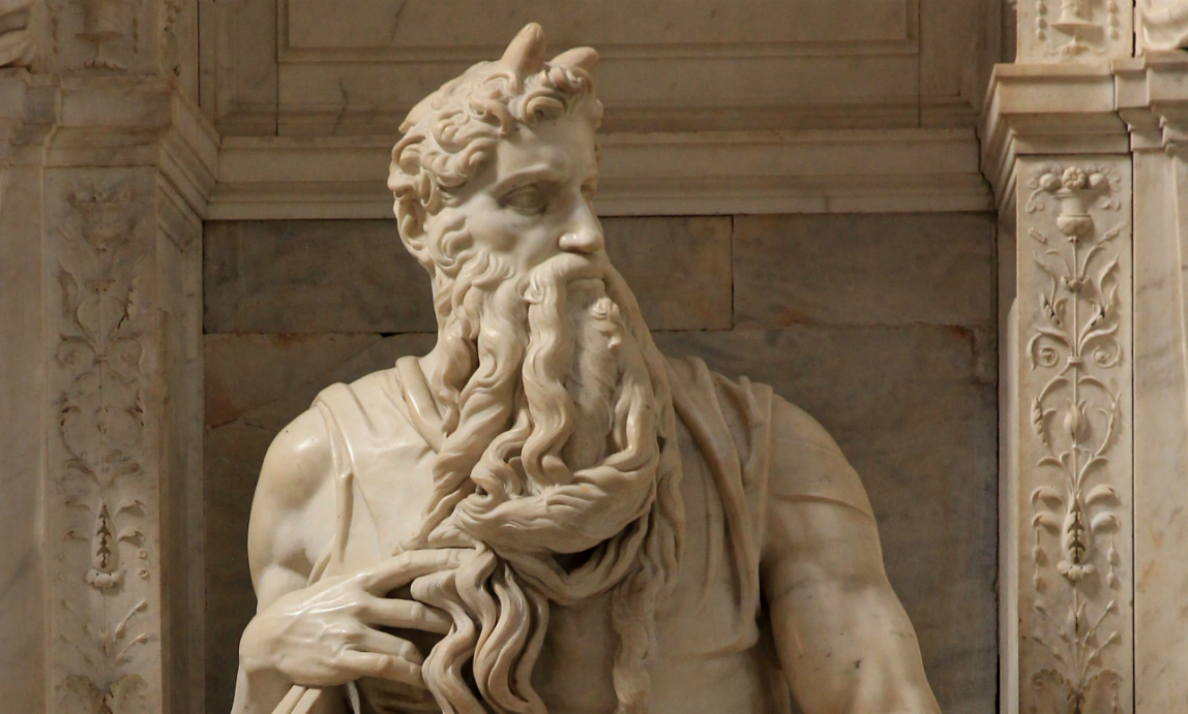

Michelangelo, Tomb of Pope Julius II, completed 1545, marble, in San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome (photo: Darren and Brad, CC BY-NC 2.0)

This chapter explores art and architecture created in the contexts of renaissance court life (art produced in the Italian republics may be explored in another chapter). The term “court” designates the ruler of a territory and his entourage of courtiers (those who serve him and his family) and administrators as well as the physical space—the palace or castle—they occupy. A ruler may be referred to as a Lord, a sovereign, a prince, or a monarch, but these terms all mean the same thing: this man (and very occasionally woman) was the absolute authority in his domain. As we shall see, the opportunities and challenges in navigating the unique social and political environments of states ruled by a sovereign provided rich contexts for the development of visual art.

Sovereign Rule

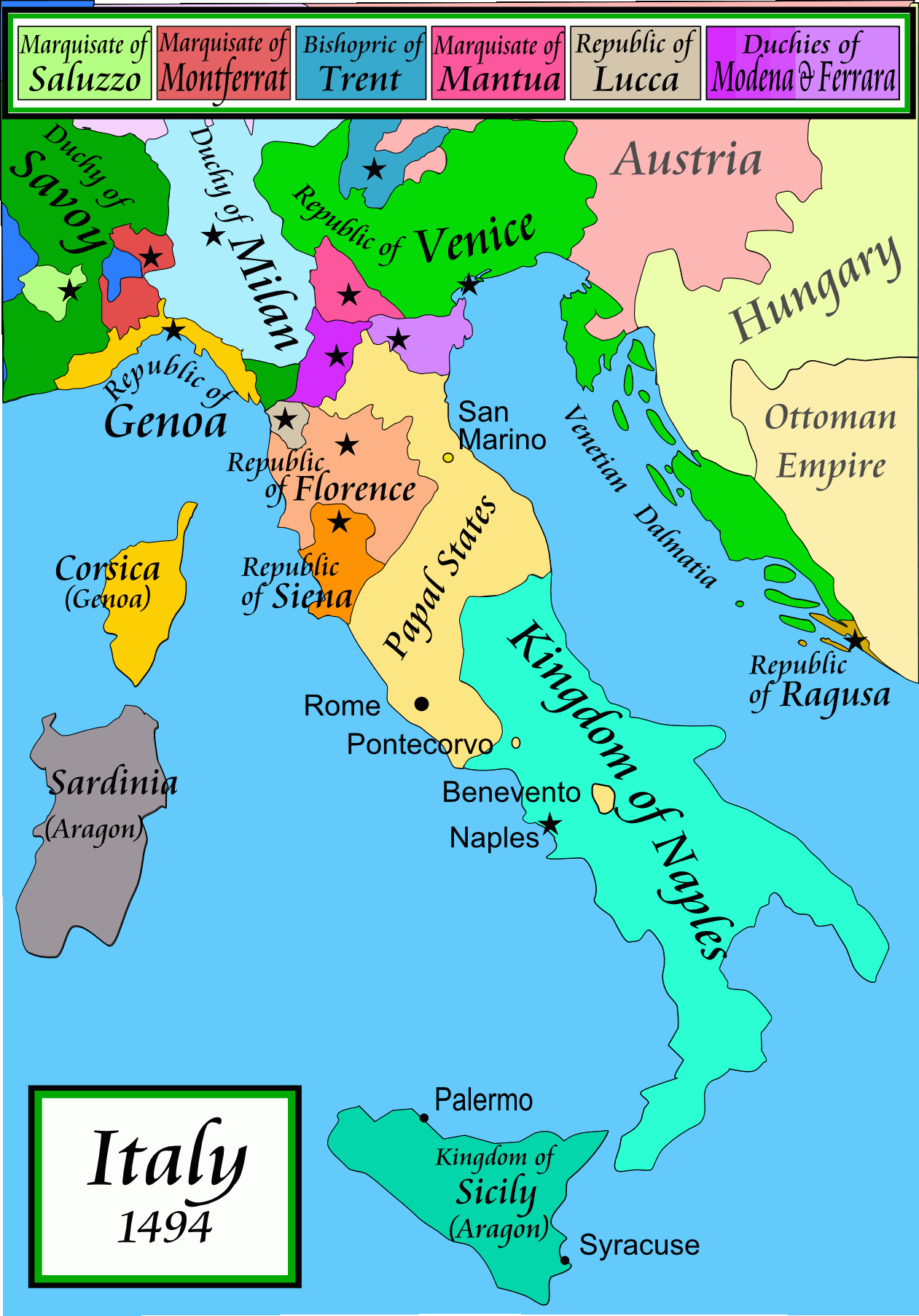

Map of Italy in 1494 showing republics and sovereign states.

The diversity of visual trends in the art of the Italian renaissance reflects the diversity of political regimes across the peninsula. While some Italian renaissance city-states functioned politically as republican oligarchies, others were governed by a sovereign—a hereditary ruler (and his family) who exerted almost absolute authority. The territories under sovereign rule may themselves be divided into three categories:

- the numerous small principalities of Northern Italy, including Ferrara, Mantua, Urbino, and Milan

- the Papal States, governed by the Church and headed by the Pope

- the Kingdom of Naples and Sicily, united as a single kingdom by the Spanish house of Aragón in the 15th century.

In most sovereign states, the prince and his court, were at the center of political and social life. Like the republican city-states, these territories were home to a rising merchant class who, alongside the hereditary nobility, were the primary patrons of art. At the renaissance court (papal or secular) it was the individual tastes of the prince or pope that determined regional style—not the collective aesthetic preferences of merchants and bankers as in the republics.

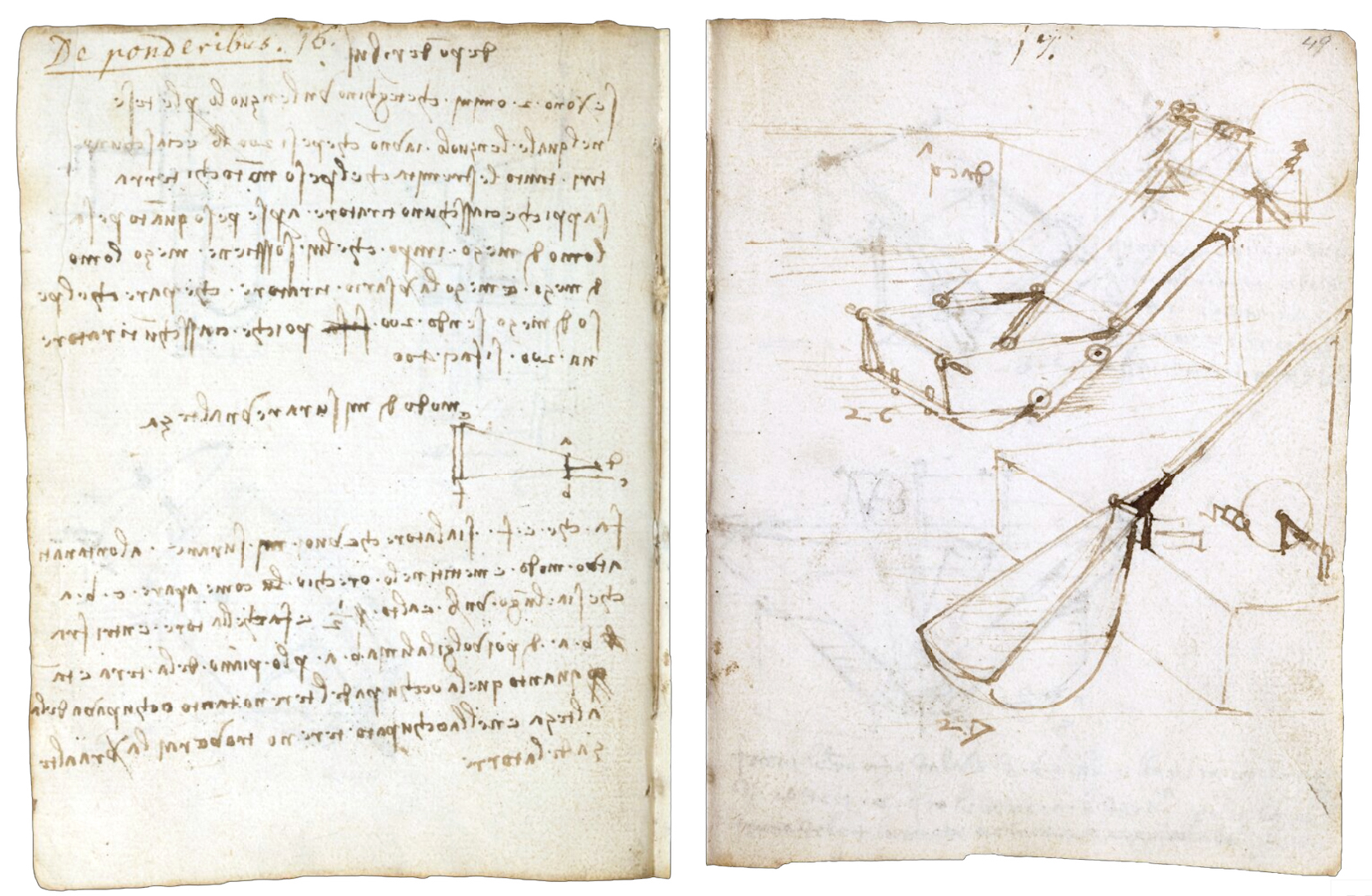

Leonardo da Vinci, Drawings of hydraulic and engineering machines, 1487–1505, Codex Forster I (National Art Library, Museum no. MSL/1876/Forster/141/I)

For visual artists, many of whom worked for clients both in republican and sovereign states, navigating the needs of a prince provided opportunities and challenges. Leonardo da Vinci found seventeen years (1482–99) of steady employment at the court of Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan. Like many court artists, Leonardo engaged in a variety of pursuits in Milan including designing weapons, buildings, and machinery and designing spectacular court festivals. At court, an artist had the prospect of steady employment and the chance to rise in the court social hierarchy (some renaissance court artists were even knighted!), often with a guaranteed salary as well as living and clothing allowances. There were challenges as well. Courts were places of social competition, resentment, and intrigue. And, when Ludovico Sforza was ousted from power in 1499, Leonardo was without a job.

Before moving forward with this chapter, let’s consider the broader context of renaissance Italy.

Introduction to art in Italy, c. 1400–1600

Italy did not exist during the period that we call the Renaissance (roughly 1400–1600 C.E.). The modern nation-state that we know today as Italy wasn’t born until the late 19th century. Nor were there such people as “Italians.” Instead we had Florentines, Venetians, Romans, Genoese, Sienese—a person’s identity was tied to the specific city-state or region in which they lived. Although interconnected through social, economic, and political networks as well as a shared ancient Roman past, the Italian city-states were largely independent from one another. Each had its own dialect as well as distinct political and social formations and cultural traditions.

So, if there is no such thing as “renaissance Italy,” there can’t be “Italian renaissance art,” right? Right! Well, technically anyway. While we often frame our considerations of art produced by people living on the Italian peninsula between 1400 and 1600 as “Italian renaissance art,” this generalization can be misleading. Florentines living in 1500 certainly did not see themselves (or their art) to be the same as their Venetian peers. Try asking a New Yorker how much they have in common with a Los Angelino and you’ll get some idea of what I mean. That said, there are shared qualities of form and content across the peninsula (artists traveled and so did styles and subjects) that allow us to recognize general “Italian” trends making “Italian renaissance art” a useful if imperfect designation.

There were three main types of political organization amongst the Italian city-states:

- territories that functioned as republics with governors elected from among the social and economic elite

- sovereign states, governed by a despot who had almost absolute authority; and

- the Papal States, regions under the direct governance of the Catholic Church and headed by the Pope.

These categories were not strictly fixed. The Republic of Florence, for example (founded in the twelfth century), ceased to exist in 1532 when the powerful Medici family came to rule the city-state as dukes, owing their allegiance to the Holy Roman Emperor.

Just like today, the political organization of a renaissance territory had a big impact on people’s lived experiences. It is one thing to be the subject of a king, it is very different to be an elected official in a republic. The same can be said about art. Imagery created within a republican context develops differently than that created in a monarchy. In this chapter, we will explore art and architecture created within the context of sovereign rule. Another chapter looks at art made in republics.

To help understand the art in sovereign states, you will consult a helpful primer to learn more about the people, places, and objects we consider when we study what we call Italian renaissance art.

Read a helpful primer about the Italian renaissance

/1 Completed

Papal States

Titian, Portrait of Pope Paul III, c. 1543, oil on canvas, 113.3 x 88.8 cm (Museo di Capodimonte, Naples; photo: FDRMRZUSA, public domain)

What if your overlord was not only divinely ordained to rule, but was—quite literally—God’s right hand man? Such was the case in the Papal States. These were territories in central Italy under the direct dominion of the Catholic Church (756–1870) and headed by the Pope. As Vicar of Christ and heir of Saint Peter (head of Christ’s Apostles and first Bishop of Rome), the position of Pope straddles the sacred and secular realms like none other. The Pope is an elected official chosen by the College of Cardinals. The men chosen as Pope during the renaissance often came from wealthy families and well-connected families, whose interests the pontiff would be expected to promote. Of course, the Pope is also understood to be God’s chosen representative on earth (who could ask for a better job recommendation?). In Christian territories, the Pope’s authority technically superseded that of all other temporal rulers, even if in practice the Pope rarely enjoyed such power. The Pope ruled over a court made up of ecclesiastic officials, including the College of Cardinals who advised the Pope, helped govern, and selected the pope’s successor.

Saint Peter’s Basilica (Basilica Sancti Petri), begun 1506, completed 1626, Vatican City

Adorning God’s Capital City

For renaissance Europeans, Rome was a place of sacred pilgrimage and fallen antique glory, where mortality was equally manifest in the tombs of Christian martyrs and the ruins of ancient Rome. Officially designated caput mundi, “capital of the world,” Rome was at the center of Christian secular and religious life. The diverse territories of the Italian peninsula shared an understanding of Rome as the capital city of their faith. As a Christian capital, however, renaissance Rome left much to be desired: the city was plagued by factionalism, poverty, crime, and disrepair. In fact, for almost seventy years (1309–76), the papacy had abandoned Rome altogether and seven consecutive popes ruled from the French city of Avignon. Power struggles, including those among competing Popes (known as the Western Schism of 1378–1420), left Rome bereft of consistent management. Restoring Rome to its former (ancient) glory—indeed surpassing the magnificence of the ancient Roman Empire—became a primary concern of renaissance popes.

Donato Bramante, Tempietto, c. 1502, San Pietro in Montorio, Rome

Reengineering the urban center by restoring aqueducts, improving roads and adorning the city and Vatican with art and architecture that conveyed appropriate magnificence prompted a renaissance—a true re-birth—in Rome. Successive popes sought to make their mark upon the city. So too did others who lived there or who hoped to make their presence felt in the Capital of Christianity from afar, such as the Catholic Monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabel of Spain who commissioned the exquisite Tempietto from Donato Bramante.

Read essays and watch videos about adorning God’s capital city

St. Peter’s Basilica, Rome: Tearing down the earlier building was a bold maneuver that gives us a sense of the enormous ambition of Pope Julius II, both for the papacy as well as for himself.

Read Now >

Donato Bramante, Tempietto, Rome: The Catholic Monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabel of Spain, commissioned the Tempietto to make their presence felt in the Capital of Christianity.

Read Now >

Perugino, Christ Giving the Keys of the Kingdom to St. Peter: This large scale fresco, commissioned for the Sistine Chapel, is part of the New Testament narrative cycle depicting events from the life of Christ on the north wall of the chapel.

Read Now >

Michelangelo, Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel: An ambitious ceiling commissioned by Pope Julius II.

Read Now >

Michelangelo, Studies for the Libyan Sibyl: The drawing showcases Michelangelo’s impeccable abilities as a draftsman as he prepared for what would become part of the most expansive fresco commission of his career.

Read Now >

Michelangelo, Last Judgment, Sistine Chapel: The Last Judgment was one of the first art works Paul III commissioned upon his election to the papacy in 1534.

Read Now >/7 Completed

Raphael, and Art in Private Spaces of the Papal Court and Its Courtiers

Like all other political leaders, the ruling Pope used art and architecture to help secure his position. Imagery was created that linked Papal authority to biblical precedents and celebrated the administrative skills of the Pope.

Raphael, School of Athens (left) and Disputà (right), fresco, 1509–11 (Stanza della Segnatura, Papal Palace, Vatican)

Perhaps no artist in history is understood to have better served the interests of his papal patrons than Raphael. In his short life, the artist skyrocketed to fame, moving to Rome in 1508 as an up-and-comer and swiftly becoming the most sought-after artist of the region. Until his untimely death in 1520 at the age of 37, Raphael moved among the highest social and intellectual circles and, with his large workshop, created imagery that magnified the splendor of the Papacy and the elite of Rome. Raphael’s Roman works presented in this section demonstrate how effectively the visual arts could serve Papal interests.

Watch videos and read essays about Raphael, and art in the private spaces of the papal court and its courtiers

Raphael, Portrait of Pope Julius II: An influential papal portrait that became a model for hundreds of years.

Read Now >

Raphael, Pope Leo X: From Raphael’s portrait, one would never guess that Leo’s policies were ripping Christendom apart and would directly lead to the Protestant Reformation.

Read Now >

Raphael, School of Athens: One fresco in a room was used by Julius II as a library and private office.

Read Now >

/4 Completed

Regions ruled by a sovereign

Northern Italian city-states, including Verona, Piacenza, Ferrara, and Rimini, where a single sovereign and his attendants governed, were called signorie, or Lordships. The ruler, or prince, of the territory and his court managed all affairs of state. The signorie may be further divided into two categories: those that were technically fiefs of the Holy Roman Empire and those owing allegiance to the Pope. These states were required to pay taxes or give military service to their papal or imperial overlords and answer to their superior authority. In practice though, these states were virtually independent and their rulers enjoyed largely unfettered authority. Italian courts were well connected with each other, as well as with foreign courts, especially those of Spain, Germany, Portugal and Burgundy. Marriage alliances offered concrete ways of forging bonds that transcended political interests.

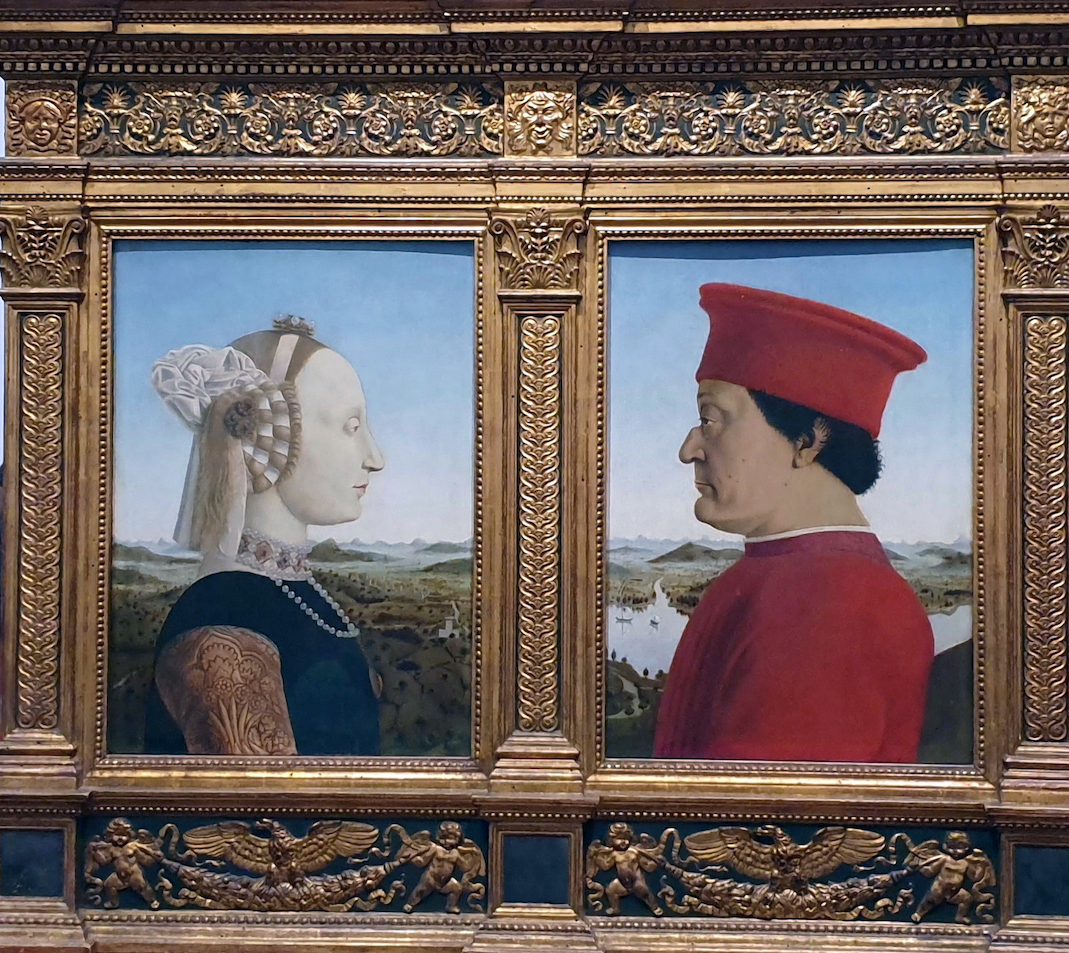

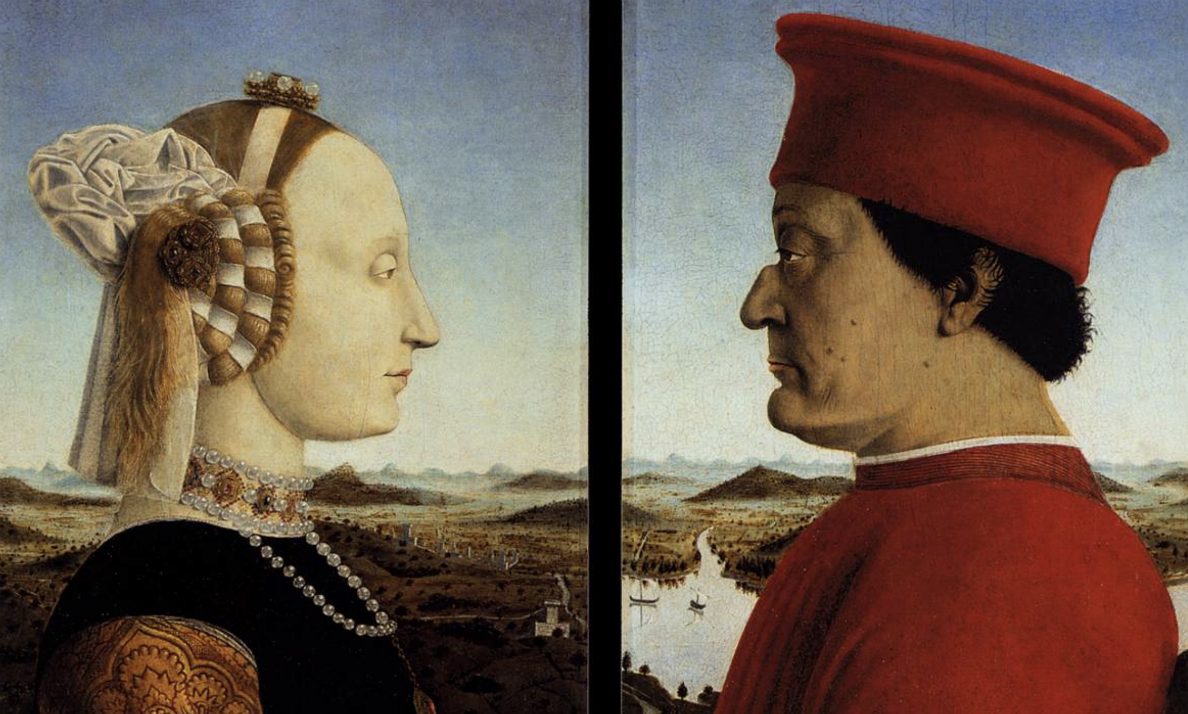

Piero della Francesca, Portraits of the Duke and Duchess of Urbino (Federico da Montefeltro and Battista Sforza), 1467–72, tempera on panel, 47 x 33 cm (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence)

The ruler was expected to display magnificence which meant many things. Ruled by the concept of decorum, magnificence meant embracing the right things, in the right way, at the right time. It meant emulating the splendor of the ancient Roman Empire while not succumbing to ostentation. It meant demonstrating material wealth but with dignified restraint. The magnificence of the ruler was expected to reflect the Glory of God and justify the ruler’s authority as God-given. How a prince dressed, walked, talked, danced, and prayed was all carefully calculated to convey magnificence. Nobility was also articulated through the magnificence of the objects and buildings one commissioned.

Defining the princely self in portraiture

Portraits were one way that a ruler could establish his authority and the preeminence of his family and display magnificence. Portraits were traditionally associated with the nobility and the earliest independent portraits of the Renaissance record the features of rulers. Looking at the portraits that survived of ancient leaders, particularly the ancient Roman Emperors, renaissance princes saw value in this mode of commemoration.

Gentile Bellini, Portrait of Sultan Mehmet II, 1480, oil on canvas, 69.9 x 52.1 cm (The National Gallery London. Layard Bequest, 1916. Currently on loan to the Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

A portrait prompted associations with imperial grandeur and allowed rulers to tailor their public image. Italian portraits idealized the sitter communicating his (or sometimes her) exemplary virtues. We might think of portraits of renaissance sovereigns as a form of princely branding, a way of associating the sitter with qualities that justified his position. For the prince’s female consort, portraiture might demonstrate her ideal femininity and celebrate her role in the continuation of the hereditary dynasty.

Watch videos and read essays about defining the princely self in portraiture

Piero della Francesca, Portraits of the Duke and Duchess of Urbino: Inside and outside, these panels are suffused with symbolism and the two stark profiles exude formality and power.

Read Now >

Gentile Bellini, Portrait of Sultan Mehmed II: Gentile Bellini’s portrait of Mehmed II has been re-interpreted and understood many times since it was produced nearly 550 years ago.

Read Now >

Bronzino, Portrait of Eleonora di Toledo with her son Giovanni: A portrait of the Dutchess of Florence, Eleonora di Toledo, with her little son Giovanni in luxurious clothing.

Read Now >/3 Completed

Reflecting the Prince in Public and Private

Art commissioned by the ruler and his family displayed in public spaces and within the princely household served to legitimize and stabilize the sovereign’s power. Works of visual art were also often given as gifts to courtiers and to rulers of foreign territories (recall that “foreign” often meant another Italian state) as strategic acts of diplomacy. In short, everything patronized by the prince and his family was a reflection of his authority.

![Giancristoforo Romano, Portrait medal of Isabella d’Este [obverse], 1495 – 1498, gold with diamonds and enamel, 7 cm diameter (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Medal.jpg)

Giancristoforo Romano, Portrait medal of Isabella d’Este [obverse], 1495–98, gold with diamonds and enamel, 7 cm diameter (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

In the Palace: Defining the Prince in the Private Sphere

The residence of a ruler was not a wholly private home, no more that the White House is the private dwelling of the U.S. President. The princely palace was the center of political and economic administration. Life at the palace was ever changing, ambassadors regularly came and went, and visiting foreign dignitaries paid court. The palace was also where the prince and his family resided. It is where they slept, ate, dressed and pursued private worship. It is where they collected art and works of literature, where they danced and feasted. The palace had to communicate the nobility of the ruler and his family to those who visited while also mirroring to the ruler his own virtue.

Watch videos and read essays about defining the prince in the private sphere

Andrea Mantegna, Camera Picta (Camera degli Sposi): A fantastically frescoed room in the Ducal Palace in Mantua.

Read Now >

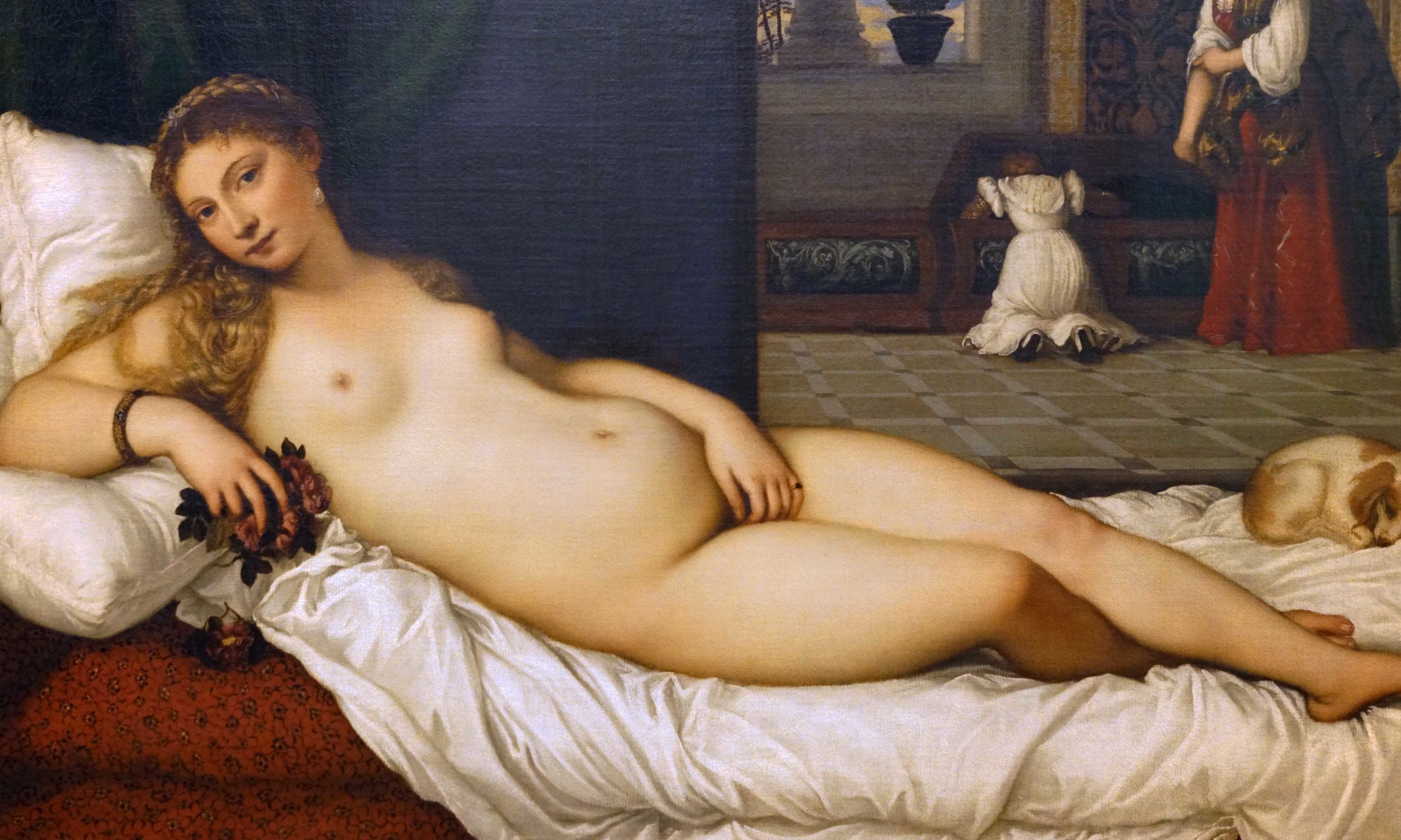

Titian, Venus of Urbino: The installation of the Venus of Urbino in the ducal guardaroba in Urbino meant it was intended for private viewing.

Read Now >

Nicola da Urbino, Plate with the Story of King Midas: A dinner service for Isabella d’Este.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Guido Mazzoni, Lamentation, 1480s, Ferrara, Italy (photo: Sailko, CC BY 3.0)

In the City: Princely sponsorship in public spaces

The renaissance ruler was both a political and devotional leader. While not holding ecclesiastic office, the ruler was expected to perform as a model Christian, caring for the physical and spiritual well-being of his people. Some renaissance rulers had direct roles as military captains, leading troops as a means of securing political power and wealth for their state. By sponsoring works of art and architecture in the public sphere, the prince could demonstrate his rightful guardianship.

Watch videos and read essays about princely sponsorship in public spaces

Guido Mazzoni, Lamentation, Ferrara: Clay becomes flesh in the remarkable terracotta sculptures of artist Guido Mazzoni that also include Duke Ercole d’Este and his wife, the Duchess Eleonora of Aragon.

Read Now >

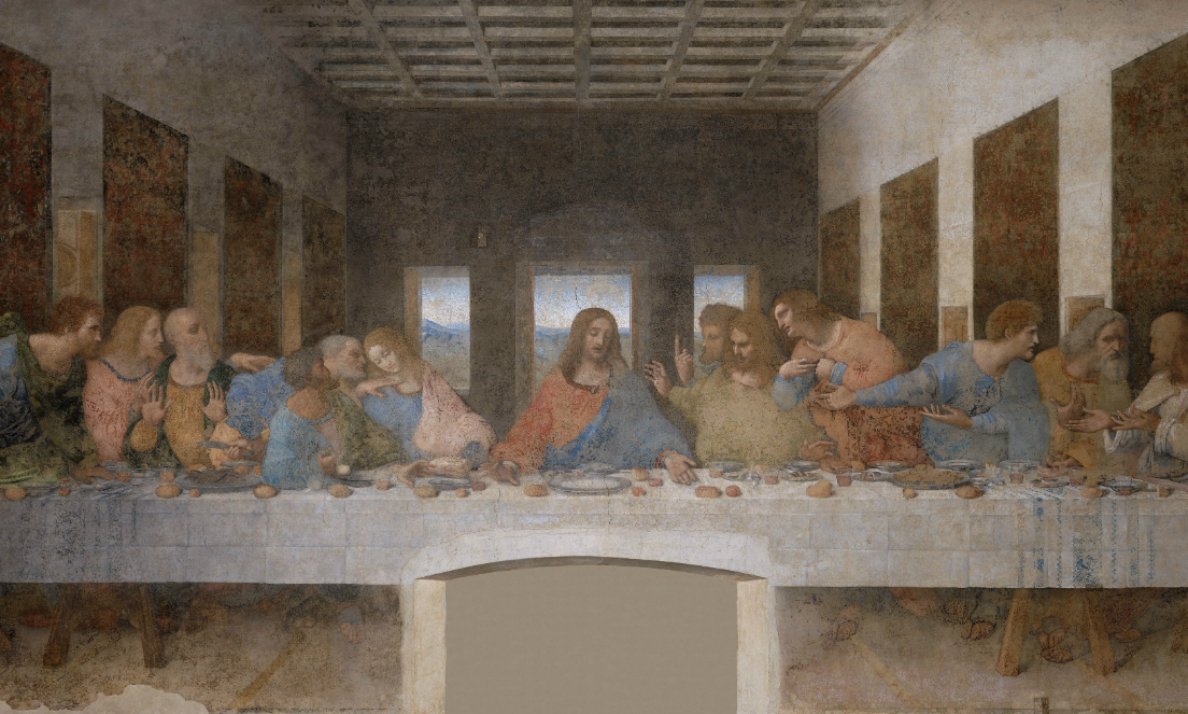

Leonardo, Last Supper: A fresco commissioned by Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan for the renovation of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan.

Read Now >

Benvenuto Cellini, Salt Cellar: Cellini’s salt cellar was prized as luxury tableware and was also an intellectual conversation starter, originally commissioned by Florentine Cardinal Ippolito d’Este.

Read Now >/3 Completed

In Italian renaissance states ruled by a sovereign, the individual triumphed over the collective. It was the interests of the ruler and his family that set the tone for artistic production, shaping style, choices of media, and even subject matter. A ruler’s policies and taste alike reflected his magnificence.

Notes:

[1] Francesco Ariosto, Dicta de la Fortunata e Felice Entrata in Roma de lo Illustrissimo Duca

Borso, quoted in Enrico Celani, “La venuta di Borso d’Este in Roma: L’anno 1471,” Archivio della R.

Società Romana di Storia Patria 13, nos.3–4 (1890): 361–450, 401: “il nostro divo, pio et excelso

signore succedea tutto lieto e giocondo e signorile e respiandente cum quel so cesareo aspecto ornado

d’oro e giemme, su quel magno dextriero tuto refulgente.”

Key questions to guide your reading

How did the taste of an individual renaissance ruler influence the development of visual art in his territory?

How did a sovereign communicate his magnificence? Why was this important?

What challenges faced renaissance popes in their capital city? How did popes use art and architecture to legitimize their position?

Jump down to Terms to KnowHow did the taste of an individual renaissance ruler influence the development of visual art in his territory?

How did a sovereign communicate his magnificence? Why was this important?

What challenges faced renaissance popes in their capital city? How did popes use art and architecture to legitimize their position?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

Apostle

Basilica

Bishop

Cardinal

Chivalry

College of Cardinals

Contrapposto

di sotto in sù

Fresco

Greek Cross

Humanism

New Testament

Old Testament

Pope

Saint Peter

Sovereign