Identity politics, from the margins to the mainstream: As the ideas and perspectives from non-white artists, queer artists, and those with other intersectional identities were given space in the museum throughout the 1990s, the terrain of art history began to shift as well.

Read Now >Chapter 57

Responding to the early modern European tradition

Contemporary responses to the European tradition

A quick internet search for “masterpiece” or “art history” turns up overwhelmingly European artworks. Like many other academic disciplines, art history as a scholarly specialty developed in an exclusionary elite European context. It is therefore unsurprising that many academic disciplines—with art history no exception—have supported the maintenance of class distinctions and hierarchies. Traditional art history survey courses have favored a relatively small group of European and U.S. artworks. [1] Artistic training too has emphasized European “masterpieces” as models for budding artists. Even while art history as a discipline and textbooks like this one work to correct course with a global and non-eurocentric approach, art history in the popular imagination looks very European—and very White. [2]

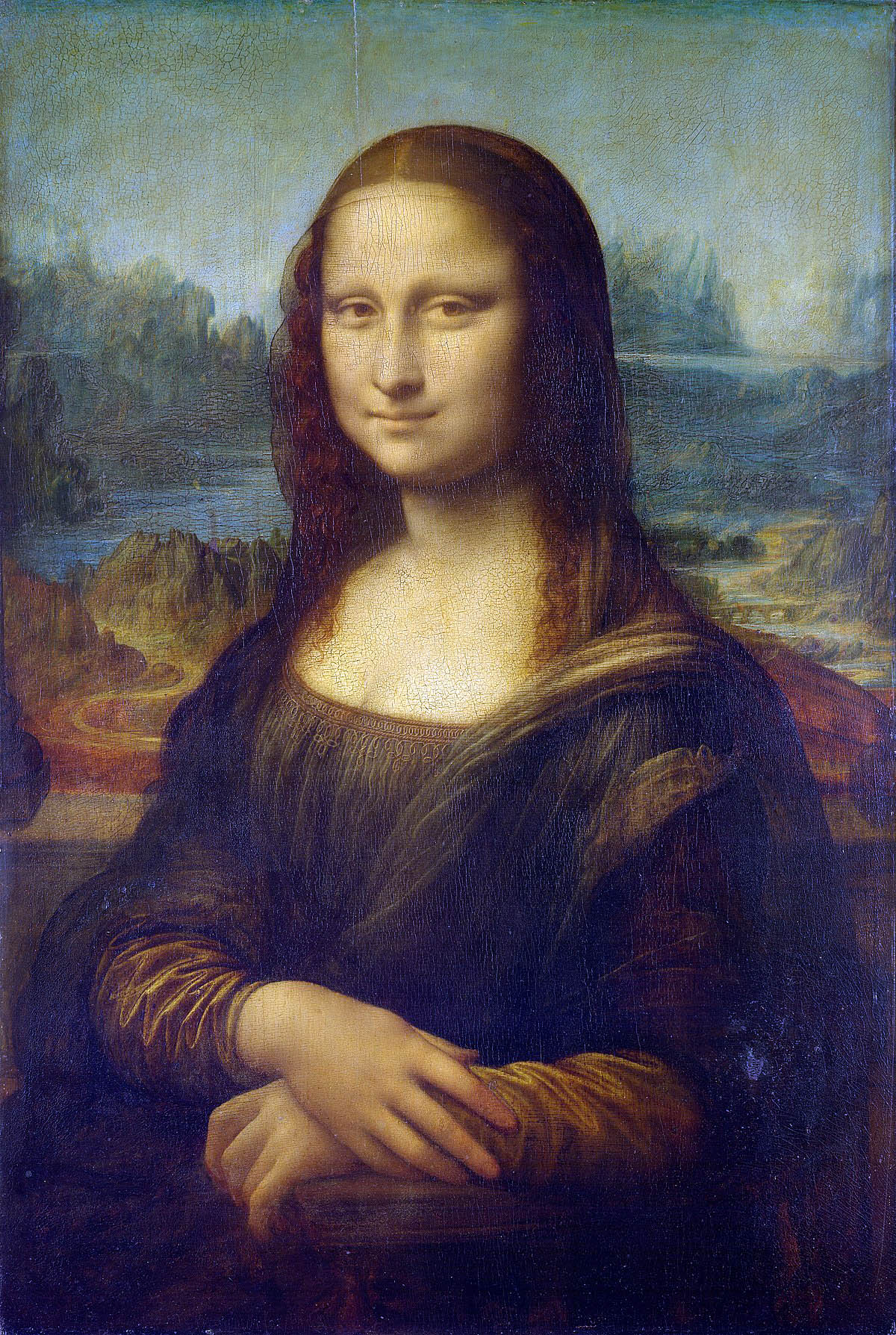

Leonardo da Vinci, Mona Lisa, c. 1503–05, oil on panel, 30-1/4″ x 21″ (Musée du Louvre)

Many famous European artworks did not explicitly promote racism or a racial ideology when first created, but over time have accrued new meanings and functions. Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa isn’t just a portrait of a sixteenth-century merchant’s wife anymore. The image hailed as a “masterpiece” adorns souvenir mugs at the Musée du Louvre in Paris where the artwork is housed. Its high cultural status helps to justify the museum’s position as a premiere cultural center. In turn, the Musée du Louvre’s status allows France to lucratively license the museum’s name to the Louvre Abu Dhabi museum in the United Arab Emirates. The idea of Whiteness was solidified a couple of centuries after the Mona Lisa was painted, as Europe created a unified racial identity to contrast themselves against other peoples. Not only could artwork project cultural and racial ideologies, some objects originally unconnected to that ideology could be pressed into service as representatives of cultural ideals. As a symbol of elevated art and culture, the Mona Lisa also carries with it the idea that all Europeans are unified in Whiteness.

This chapter addresses:

- reimagined protagonists

- post-colonialism (the era after colonialism)

- the iconography of reclining female figures

- transformed narratives

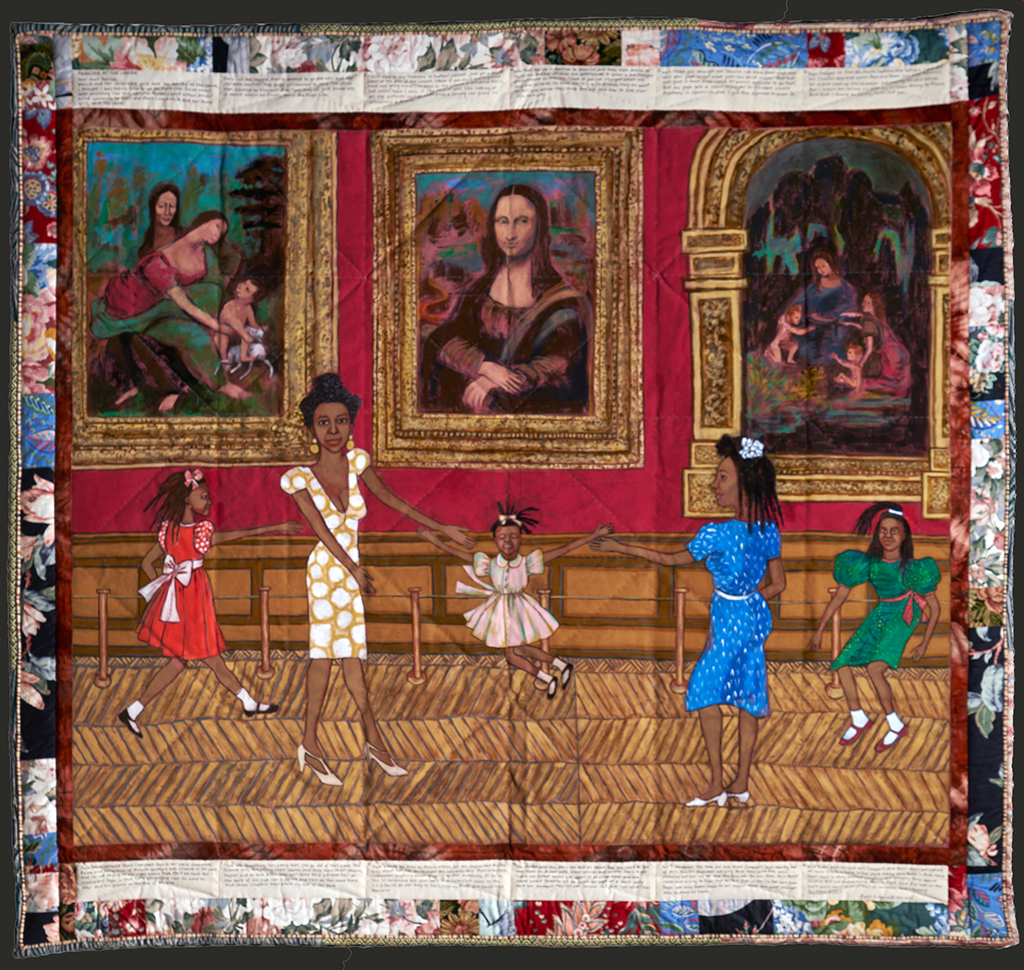

Faith Ringgold, Dancing at the Louvre, 1991, acrylic on canvas, tie-dyed, pieced fabric border, 73.5 x 80″, from the series, The French Collection, part 1; #1 (Gund Gallery, Kenyon College)

Contemporary artists, especially artists of color, engage with this tradition in ways that question the centering of Whiteness. Famous compositions and iconographic tropes have become sites of resistance to well-worn narratives/ideologies. By locating the conversation within famous artworks, artists stage canonical works of art history as a location to rework cultural values. These new works address the high status afforded specific European artworks and confront the value systems and ideologies that have turned a few select objects into exemplars and ambassadors of a system that upholds some cultures and makers over others.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries Europe adopted a developmental model of human history that imagined “civilization” as the desired end result of a progression from a primordial “state of nature” maturing through stages of “savagery” and “barbarism.” Unsurprisingly, European definitions of “civilization” described characteristics of European cultures.The hierarchy that imagines European cultures at the apex of civilization assigns high value to European art objects.

Reimagining famous European artworks in new guises or through a post-colonial gaze involves using the high status of iconic art objects to question the values that have upheld them as masterpieces. Much of this art challenges our understandings of established iconographies and conventions about art, people, and history. Seeing a person of color in the familiar form of a White woman reclining on a couch can surprise a viewer into reconsidering assumptions.

Sometimes reimagining canonical works takes the form of reconceptualized protagonists that upend who the heroes are in a work of art, and what an idealized body can be. Other times, artists reveal the conditions of colonialism and enslavement that supported the wealth and calm pictured in historical artworks. These artworks rely less on changing hierarchical structures than revealing them.

Interestingly, while contemporary works of art challenge, reimagine, and even poke fun at their European predecessors, they nevertheless reinforce the canonical status of the earlier artworks, thereby strengthening the cultural importance of the European canon. To understand the later artwork, one must understand the earlier artwork. It’s not a one way street, though: their critique irrevocably changes the way we look at the historic artwork.

After reading this chapter, you’ll gain a better understanding of why dismantling the eurocentrism of art history matters to many people and some of the ways eurocentrism is being challenged. This chapter demonstrates the enduring legacy—or haunting specter—of European art history. As we look towards the future, artists ask us all to consider what role we want European art (history) to play in our society when so many people can’t see themselves represented fairly within it.

Read and watch these introductory materials

Faith Ringgold, Dancing at the Louvre: Ringgold’s work appropriates recognizable imagery and alternative artistic practices to offer critical cultural commentary.

Read Now >/2 Completed

Reimagined Protagonists

Vittore Carpaccio, Miracle of the Relic of the Cross at the Rialto Bridge, c. 1496, tempera on canvas, 371 x 392 cm (Gallerie dell’Accademia di Venezia)

Unsurprisingly, historical European art most often portrayed protagonists, heroes, and moral figures as White, relegating people of color to minor roles and sometimes racist positions within a composition. Renaissance paintings like Vittore Carpaccio’s Miracle of the Relic of the Cross depict Black gondoliers participating in the cityscape, but not as major figures.

Filippino Lippi, Madonna and Child (detail), c. 1483–84, tempera, oil, and gold on wood, 81.3 x 59.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Other early modern paintings such as this Madonna and Child by Filippino Lippi attests to the ordinariness of enslaved Africans in European cities with the inclusion of scenes of everyday labors in the background. Exceptions exist. European art occasionally portrayed Black Africans positively as with the African magus, Balthazar or St. Maurice, a Catholic saint habitually portrayed as Black.

Lucas Cranach the Elder (and Workshop), Saint Maurice (detail), c. 1520–25, oil on linden panel, 137.2 x 39.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

On the whole, however, representations of people of color outside the borders of European Whiteness marginalized them or, worse, created stereotypes of uncivilized inferior peoples such as Theodore de Bry’s engravings of Native Americans.

Theodor de Bry, “Indians pour liquid gold into the mouth of a Spaniard,” 1594, engraving and text in letterpress, h 18 × w 20 cm, from: Collectiones peregrinationum in Indiam occidentalem, dl. 4: Girolamo Benzoni, Americae pars quarta. Sive, Insignis & admiranda historia de primera occidentali India à Christophoro Columbo, Frankfurt am Main: T. de Bry, 1594 (Rijksmuseum)

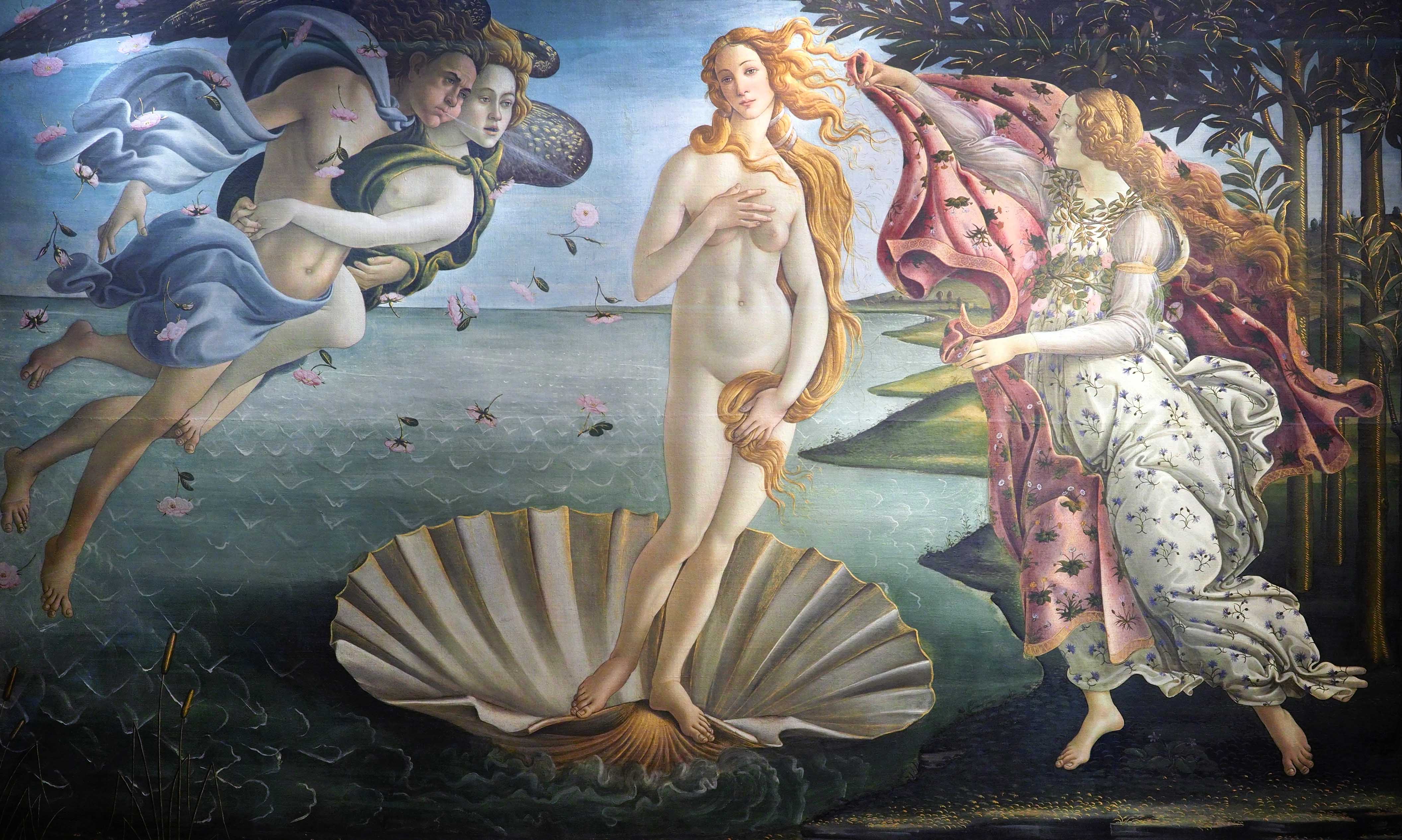

Contemporary artists who place figures of color into the role of protagonist, as heroes or representatives of an ideal, challenge preconceived notions of who can embody a hero. Artists like Harmonia Rosales and Kehinde Wiley have taken well-known European compositions like Sandro Botticelli’s Birth of Venus and Jacques-Louis David’s Napoleon Crossing the Alps and changed their environments and protagonists. Black protagonists take center stage in Rosales and Wiley’s paintings. These twenty-first century paintings assume the viewer’s familiarity with European art to reframe preexisting cultural knowledge by re-embodying its forms with new figures—people of color—whose bodies change the message.

Harmonia Rosales, Birth of Oshun, 2017, oil on linen (© Harmonia Rosales)

The familiar and unfamiliar mix in Harmonia Rosales’ Birth of Oshun from 2017. Botticelli’s famous composition of the beautiful nude woman at the center flanked by flying creatures and greeted ashore by a woman bearing billowing fabric is no longer embodied by the White figures of Greco-Roman mythology but by the orishas (deities) of Yoruba religion.

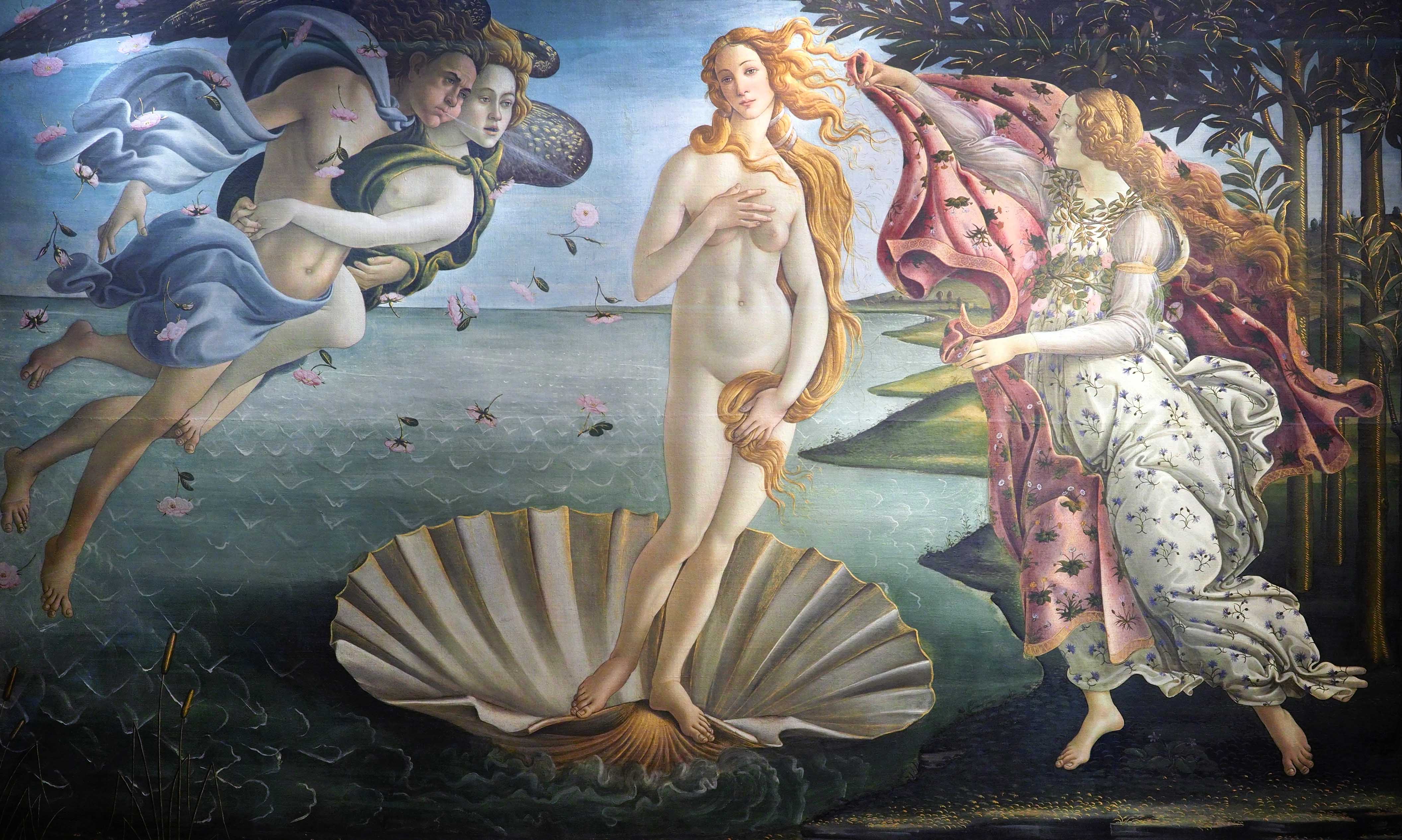

Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus, 1483-85, tempera on panel, 68 x 109 5/8″ (172.5 x 278.5 cm) (Galeria degli Uffizi, Florence)

Where the Roman mythological wind Zephyr and the nymph Chloris blow Venus to shore in the Botticelli painting, Oyá in red the goddess ruling over death and Obatalá, the Sky Father, the “sculptor of mankind,” attend Oshun, the central figure. Oshun, a Yoruba goddess of rivers and fresh water occupies the sea shell in skin shining with gold vitiligo. Offerings to Oshun are made with gold and are one way of demonstrating the central figure’s specialness. By changing Botticelli’s Venus, Rosales makes the point that there isn’t just one beauty ideal or only one way to picture a goddess. Rosales explains the alienation that can occur when ideals are embodied by only White figures:

Traditionally, we see Venus as this beautiful woman with flowy hair. My hair never flowed, so I’m wondering why this is supposed to be a painting of the most beautiful woman in the world? So I changed her up and I made her have vitiligo because imperfections are beautiful. Harmonia Rosales [3]

European artworks that featured White bodies may not have originally intended a racial message, but since their creation, they have come to embody racial meanings. Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, possibly first commissioned to celebrate a Medici family wedding and likely intended for a private space, has since come to represent ideal beauty and truth for a global audience. Post-Enlightenment cultural narratives turned these paintings into touchstones that define historic ideals of beauty as White. Because of how later eras interpreted and used certain artworks, they cannot be separated from histories of race.

Read and watch these materials about reimagined protagonists

Kehinde Wiley, Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps: Wiley strategically re-creates David’s painting from two hundred years earlier but with key differences.

Read Now >

Kehinde Wiley, Rumors of War: A monumental solution that rethinks the sculpture of Richmond.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Postcolonialism

The era of European colonialism that began at the end of the fifteenth century (with the voyages of Columbus and others) continued until the beginning of the First World War. Haiti, Mexico and Brazil gained sovereignty in the nineteenth century, but the majority of successful independence movements occurred in the twentieth century. For example, India broke from the United Kingdom in 1947 and Mozambique freed itself from Portugal in 1975. In the twenty-first century, the United Nations counts sixteen colonized territories including the US Virgin Islands, French Polynesia, and Gibraltar. [4] The term “post colonialism” therefore refers to the era after colonialism. The term most frequently describes the cultural and political situation that are a consequence of colonial occupation and twentieth-century independence movements.

An example of well-dressed gentry: Thomas Gainsborough, Mr. and Mrs. Andrews, c. 1750, oil on canvas, 69.8 x 119.4 cm (The National Gallery, London)

Contemporary artists, especially those with personal connections to colonized peoples, have sought to reveal the colonialism behind serene European compositions of well-dressed gentry, people of high social rank. European artworks dating from the Renaissance through the nineteenth century tend to picture colonizers rather than the colonized. With artworks that visualize the existence of the people who were colonized, contemporary artists draw attention to interconnected histories.

Left: Yinka Shonibare MBE, The Swing (After Fragonard), 2001 (Tate, London) © Yinka Shonibare; right: Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Swing, oil on canvas, 1767 (Wallace Collection, London; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Yinka Shonibare’s The Swing (After Fragonard) refigures Fragonard’s celebrated eighteenth-century Rococo painting by explicitly addressing class inequality and slavery in the metropole and colonies.

Trade goods can attest to interconnected histories. Some postcolonial works like Yinka Shonibare’s The Swing (After Fragonard) and Kara Walker’s Marvelous Sugar Baby draw attention to transcultural materials like “African” Dutch wax fabrics and sugar.

Kara Walker, A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby, 2014, sugar, water, resin, 35 x 75 feet (the former Domino Sugar factory in Williamsburg, Brooklyn)

Kara Walker’s monumental Marvelous Sugar Baby was made of sugar, a substance referring to the early modern transatlantic sugar trade. From the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries Europeans enslaved Africans and Caribbean islanders to produce sugarcane on large plantations that practiced chattel slavery. Walker’s Marvelous Sugar Baby takes the form of an ancient Egyptian sphinx, the most famous of which—the Great Sphinx of Giza—managed to defy colonial acquisition due to its size. Many other Egyptian artifacts were removed by French and British excavations under Napoleon at the end of the eighteenth century and the Egypt Exploration Fund in the nineteenth century and can still be seen on display at the Musée du Louvre in Paris and British Museum in London today.

Read and watch these materials about postcolonialism

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Swing: Playful and erotic scenes were popular among Fragonard’s elite clientele in 18th-century France.

Read Now >

Yinka Shonibare, The Swing (After Fragonard): Shonibare refigures Fragonard’s painting by explicitly addressing class inequality and slavery.

Read Now >

Kara Walker, A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby: A sphinx made of sugar to comment on the transatlantic slave trade—and much more.

Read Now >

Covered sugar bowl: A silver bowl tells a story about the triangle trade and the colonial table, sugar, tea, and slavery.

Read Now >/5 Completed

Re-envisioned iconography: Reclining Women

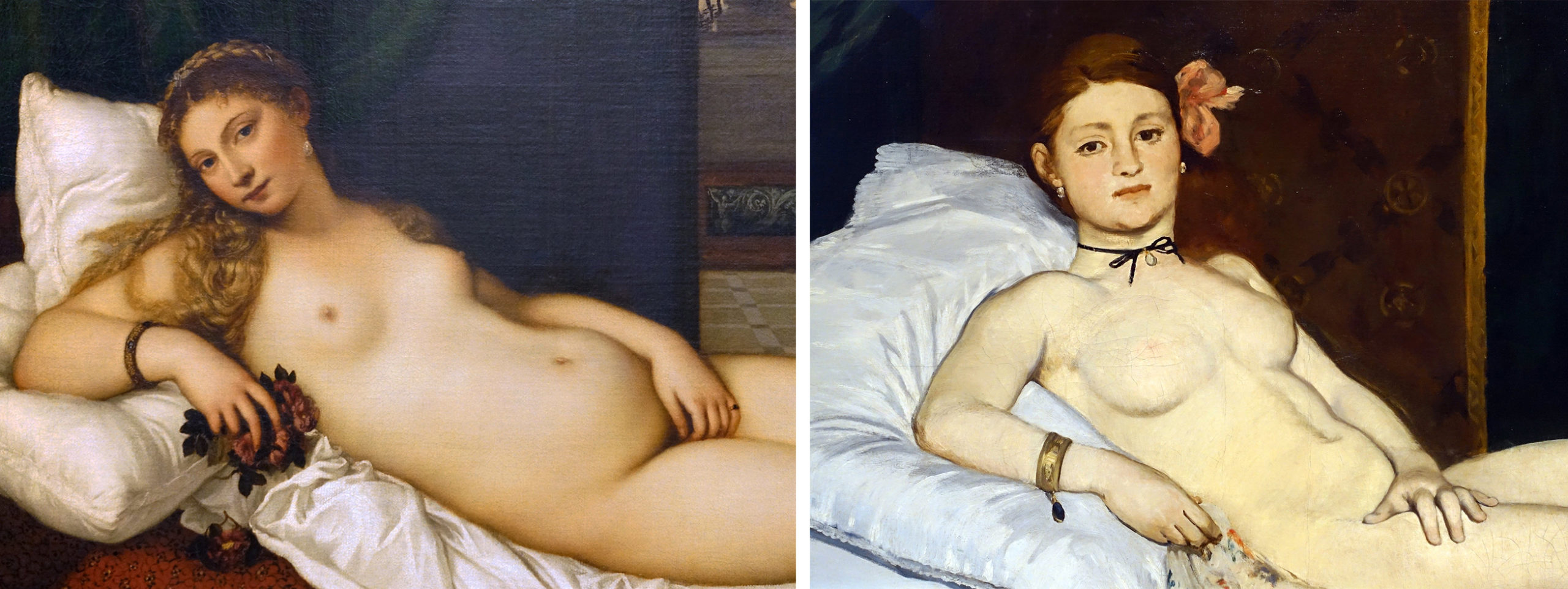

Left: Titian, Venus of Urbino, 1538, oil on canvas, 119.20 x 165.50 cm (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: Édouard Manet, Olympia, 1863, oil on canvas, 130 x 190 cm (Musée d’Orsay, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Since at least the founding of art academies in Italy and France in the early sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, artists have trained by copying the works of “old masters” that were selected as the finest representatives of a continuous tradition. Artists who embedded references to the artistic tradition won praise for their learning and skill. Raphael quoted ancient sculpture in his Renaissance frescoes. Nicolas Poussin quoted Raphael’s figures in his seventeenth-century easel paintings. Édouard Manet re-envisioned Titian’s soft nude Venus of Urbino resting in a peaceful domestic setting as a self-possessed Parisian sex worker beside her Black maid to address gender and sex politics in the mid-nineteenth century.

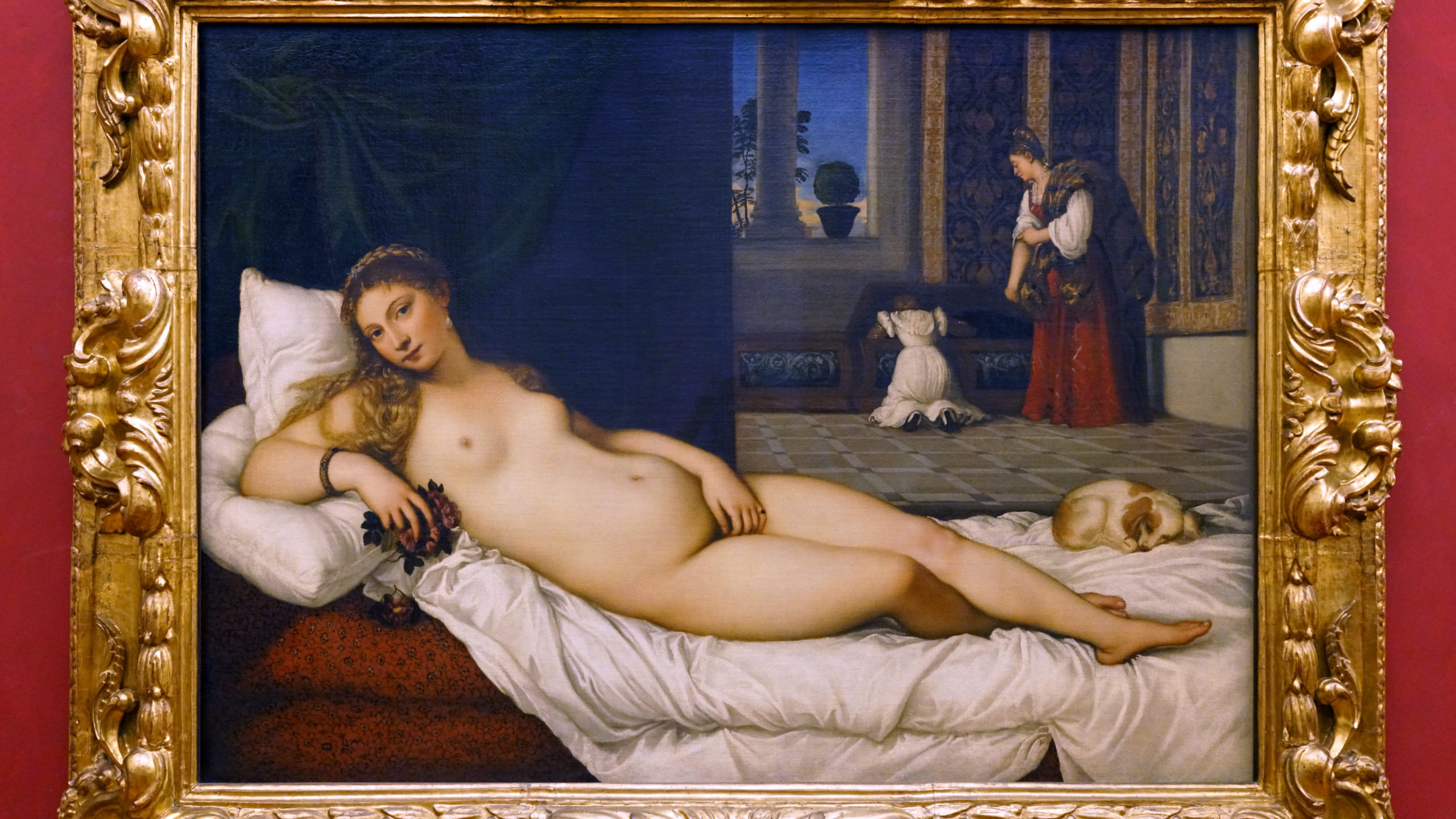

Titian, Venus of Urbino, 1538, oil on canvas, 119.20 x 165.50 cm (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence)

The contemporary works of art discussed in this chapter suggest new ways of thinking about the values embedded in the historic images by illuminating the ideologies that were once silently assumed as a given. Recumbent women, a recurring subject in European art history, often communicate objectification, sexualization, and a gendered gaze. The paintings, which eroticize female bodies as sexually available, not only assume a heterosexual male viewer, but also reinforce and perpetuate a patriarchal cultural structure that positions men as viewers and women as objects to be viewed.

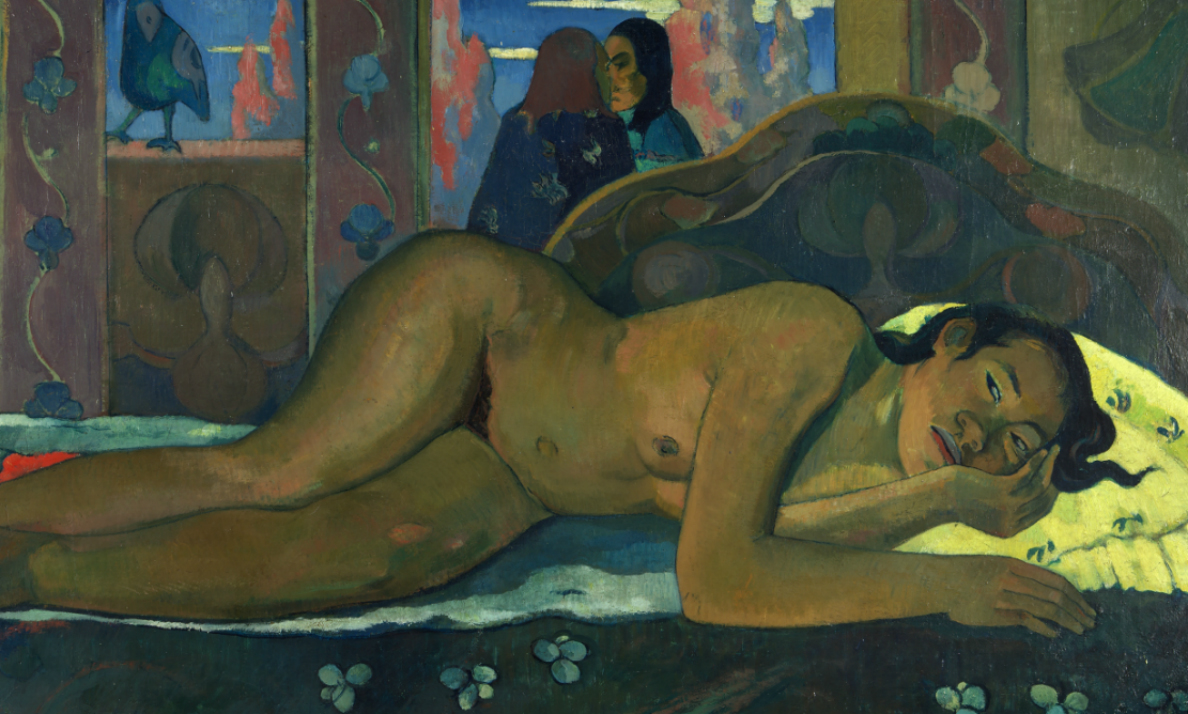

Paul Gauguin, Nevermore, 1897, oil on canvas (Courtauld Gallery, London)

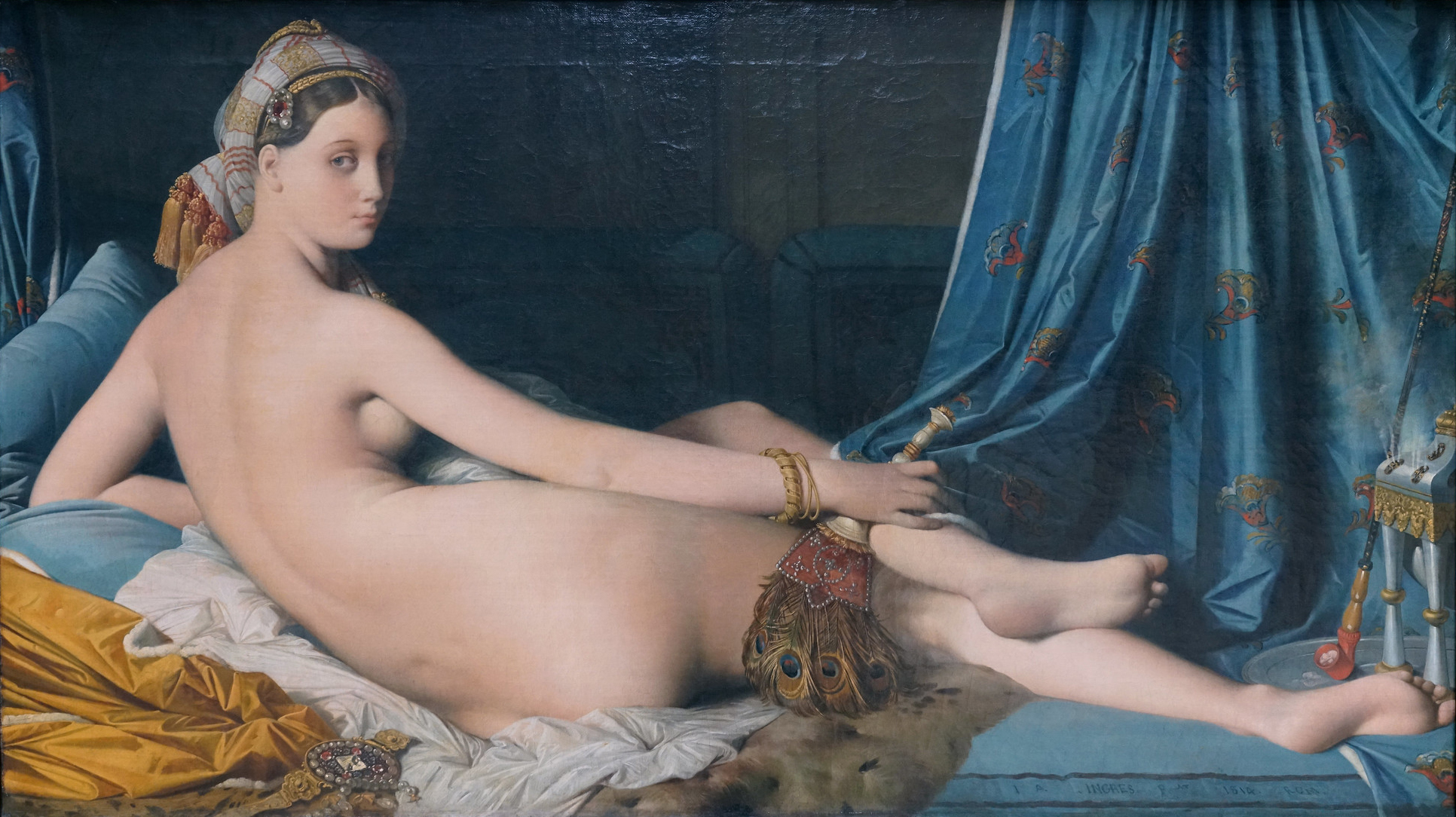

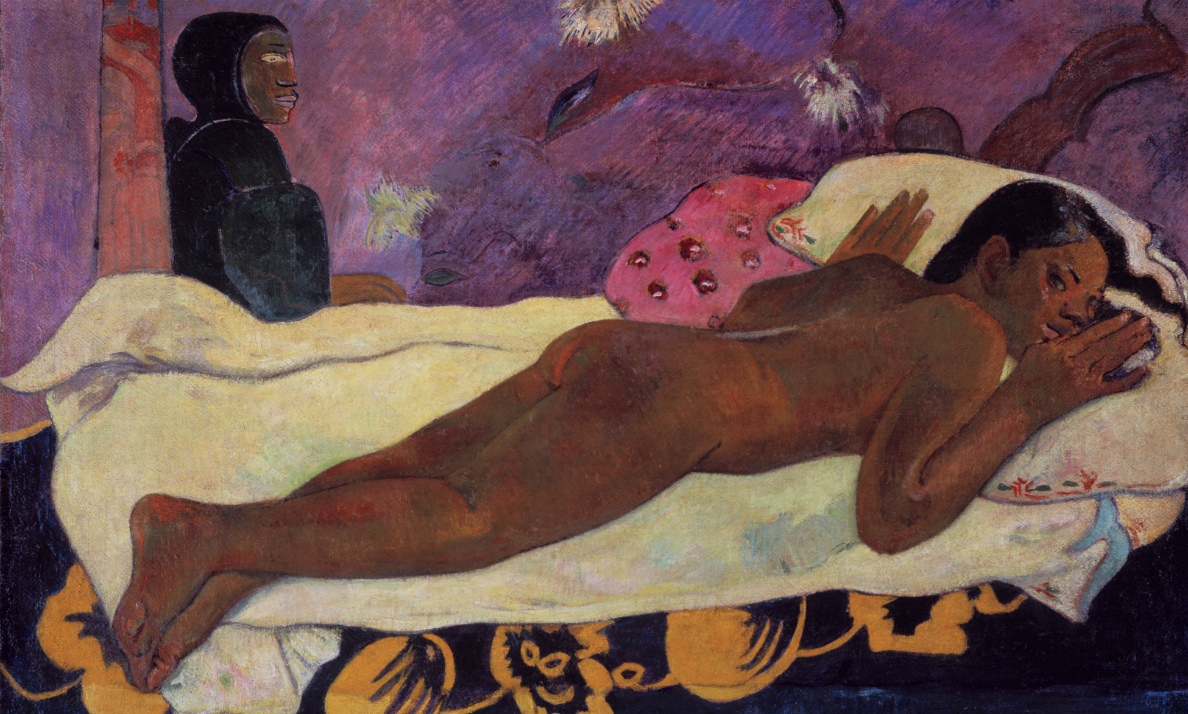

Additionally, the sexual availability of Renaissance Venuses such as Titian’s Venus of Urbino provided the foundation for Orientalist and Primitivist paintings that racialized and exoticized the preexisting iconography of the sexually available reclining woman. Ingres’s Grande Odalisque from 1814 and Gauguin’s Nevermore O Tahiti both rely on Renaissance precedents including the Venus of Urbino.

Morimura brings a queer perspective to his drag gender performance by embodying the female figures of Manet’s Olympia while also embodying his own Asianness, an underrepresented race in art history surveys that have prioritized White representations. Yasumasa Morimura, Portrait (Futago), 1988, chromogenic print with acrylic paint and gel medium, 210.19 cm x 299.72 cm (SFMoMA)

In the twenty-first century artists including Yasumasa Morimura, Mickalene Thomas, and Lalla Essaydi have re-envisioned the traditional subject of a reclining female figure, using the iconography as a site to explore sexuality, race, and gender. They approach the imagery from a position outside of European or White identity.

Mickalene Thomas, Little Taste Outside of Love, 2007, acrylic, enamel and rhinestones on wood panel, 274.3 x 365.8 cm (The Brooklyn Museum)

Morimura, a Japanese self-described “appropriation artist,” Thomas, an African-American painter, and Essaydi, a Moroccan photographer, place themselves in re-envisioned versions of famous compositions. In doing so, they exploit the genre as a site to explore sexuality, race, and gender, while disclosing the personal burden they experience as people with marginalized identities.

Lalla Essaydi, Les Femmes du Maroc: La Grande Odalisque, 2008, photograph

Read and watch these materials about re-envisioning the image of reclining female nude

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, La Grande Odalisque: The painting looks back to Italian renaissance paintings such as Titian’s Venus of Urbino, and artists like Essaydi engage with its legacy.

Read Now >

Édouard Manet, Olympia: Manet re-envisioned Titian’s earlier Venus of Urbino, placing his reclining nude in the contemporary world of Parisian prostitution.

Read Now >

Paul Gauguin, Spirit of the Dead Watching: The painting draws on the long history of the reclining female nude, including Manet’s Olympia.

Read Now >

Mickalene Thomas on her materials and artistic influences: In this video, Thomas discusses Portrait of Mnonja—as you watch, think through its precedents and how it responds to them, critiques them, changes them, and honors them.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Reimagined Narratives

Beginning in the Renaissance with writers such as Leon Battista Alberti, European art theory developed a hierarchy of subject matter that placed history painting at the top. Broadly conceived, history painting (also known as narrative painting or istoria) included classical history, mythology, and biblical stories. Later, seventeenth and eighteenth-century art academies formalized instruction in history painting and further elevated its position in European art culture. These narrative artworks depicted mostly male, White heroes. Contemporary artists ask us to imagine what other histories might look like.

Peter Frederick Rothermel, De Soto Raising the Cross on the Banks of the Mississippi, 1851, oil on canvas, 101.6 x 127 cm (Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts)

All history paintings present a particular version of history. By selecting certain figures to present as heroes or moral exemplars, history paintings shape values. For example, Peter Frederick Rothermel’s De Soto Raising the Cross on the Banks of the Mississippi romanticizes Spanish colonization of North America to provide a precedent for United States westward expansion in the nineteenth century.

History paintings often tell us more about the times they were painted than they do about the historic events they purport to be about.Dr. Anna O. Marley about Rothermel’s painting

History painting is a prime site to question inherited narratives and resist certain ideologies.

Kent Monkman (Metis, Fisher River Band), History is Painted by the Victors, acrylic paint on canvas, 182.88 x 287.65 cm (Denver Art Museum)

The title of Kent Monkman’s History is Painted by the Victors plays on a famous quotation by Winston Churchill (“History is written by the victors”). Monkman, an Indigenous North American Cree artist, places his alter ego painting Lt. Colonel George Custer’s troops within a broad landscape reminiscent of the work of Albert Bierstadt. While White artists such as George Catlin, Thomas Moran, Edward Curtis, and Albert Bierstadt painted romanticized or exoticized Native peoples and landscapes, Monkman depicts his own Indigenous point of view, demonstrating that how history is presented is often a matter of perspective.

Roger Shimomura, Shimomura Crossing the Delaware, 2010, acrylic on canvas, 3 canvas panels each: 182.9 x 121.9cm (National Portrait Gallery)

The tacit arguments history paintings make are also the subject of Roger Shimomura’s Shimomura Crossing the Delaware. As a Japanese-American who was incarcerated by his own government at a camp in Idaho during World War II, Shimomura intimately knew how narratives of race affected who the U.S. government treated as legitimately American or not. In Shimomura Crossing the Delaware, the artist reimagines Emanuel Leutze’s nineteenth-century Washington Crossing the Delaware painting of primarily White men as if it were a Japanese woodblock print featuring Shimomura himself making that American journey.

Read and watch these materials about reimagined narratives

Terms and Issues in Native American Art: This essay helps to frame Monkman’s painting History is Painted by the Victors.

Read Now >

Albert Bierstadt, Hetch Hetchy Valley, California: An example of the type of romanticized landscape that Monkman confronts in History is Painted by the Victors.

Read Now >

Emanuel Leutze, Washington Crossing the Delaware: This painting was the model for Shimomura’s reimagined narrative.

Read Now >/3 Completed

Rethinking the Canon

Contemporary artists who respond to the Eurocentric canon of art history suggest that constructing a new future will require reckoning with our past. Because of the pervasiveness of Eurocentric studio art education, art history, and exhibitions, canonical artworks can act as unifying common knowledge, but shared experience does not deny that people’s individual perspectives are shaped by their identities and experiences.

One of the strongest messages from contemporary art that rethinks the canon is that art, humans, and their history are more diverse than previously implied. Because art can serve as a site to question and reimagine inherited values and ways of thinking, where better to locate the conversation?

Notes:

[1] Compare with Keith Moxey, Practice of Theory, 1994

[2] As of 2022, some style guides capitalize “Black” when referring to race, but not “white.” Recognizing that inconsistent capitalization makes some races and ethnicities (e.g. Asian, Latino, Black) a marked category, while implying another race, lowercase “white,” is a default neutral category, this chapter capitalizes all racial designations.

[3] Sonaiya Kelley, “Words and Pictures: Viral artist Harmonia Rosales’ first collection of paintings reimagines classic works with black femininity,” Los Angeles Times September 21, 2017

[4] John Quintero, “Residual Colonialism in the 21st Century,” May 29, 2012

Key questions to guide your reading

How does historic European art frame race? How have famous European artworks been interpreted? Why would European art compositions and traditions appeal to artists of color seeking to challenge (some of) its underlying assumptions and values?

What is gained from contemporary engagement and interaction with historical forms?

How do contemporary artists help us understand the inherited European art tradition?

Jump down to Terms to KnowHow does historic European art frame race? How have famous European artworks been interpreted? Why would European art compositions and traditions appeal to artists of color seeking to challenge (some of) its underlying assumptions and values?

What is gained from contemporary engagement and interaction with historical forms?

How do contemporary artists help us understand the inherited European art tradition?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

Learn more

Carpaccio’s Miracle of the Relic of the Cross

Madonna and Child by Filippino Lippi

African magus, Balthazar or St. Maurice

Theodore de Bry’s engravings of Native Americans

Learn more about academic painting in France

Yasumasa Morimura’s Une moderne Olympia, Hyperallergic, 2018

Learn about Rothermel’s painting of De Soto Raising the Cross

George Catlin, The White Cloud, Head Chief of the Iowas

Thomas Moran, Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone

A teaching resource for Shimomura’s Shimomura Crossing the Delaware