Michelangelo, Last Judgment, Sistine Chapel, altar wall, fresco, 1534–1541 (Vatican City, Rome) (photo: Ramon Stoppelenburg CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Millions of visitors flock each year to admire Michelangelo’s ceiling paintings and the Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel—not unlike artists had, since the paintings were first unveiled in the 16th century. The muscled bodies of holy figures have been much studied and replicated over centuries, but they have also been the subject of scandal, especially the artist’s Last Judgment.

Christ, Mary, and Saints (detail), Michelangelo, Last Judgment, Sistine Chapel, altar wall, fresco, 1534-1541 (Vatican City, Rome)

Never had so much naked flesh appeared in a sacred Christian space on this scale. When the altar wall’s fresco was finished in 1541 it almost immediately caused a furor, with the author Pietro Aretino writing a scathing letter to the artist in 1545 that stated:

As a baptized Christian, I blush before the license . . . which you have used in expressing ideas connected with the highest aims and final ends to which our faith aspires. . . . Here there comes a Christian, who . . . deems it a royal spectacle to portray martyrs and virgins in improper attitudes, to show men dragged down by their shame, before which things houses of ill-fame would shut the eyes in order not to see them.Pietro Aretino [1]

Aretino, like many others, found the rampant nudity in Michelangelo’s altar wall shocking and problematic. Critics also took issue with the figures’ complex poses, the number of figures, and even the beardless Jesus (among other things).

Left to right: Saint Blaise, Saint Catherine, and Saint Sebastian. Daniele Volterra added loincloths and clothes to many of the figures in the Last Judgment, especially those in the upper half of the painting. Volterra added a purple loincloth to Saint Sebastian on the lower right, an entire outfit to Saint Catherine (wearing green), and actually chiseled out and repainted Saint Blaise (in red). Saint Blaise’s original position was more hunched over Saint Catherine’s, and critics found it too suggestive of a sexual act—especially because Catherine was completely nude. Michelangelo, Last Judgment (detail), Sistine Chapel, fresco, 1534–41 (Vatican City, Rome)

By 1565 (one year after Michelangelo’s death), the artist Daniele da Volterra was hired to paint over the most scandalous of the Last Judgment’s nude bodies, earning himself a nickname in the process—Il Braghettone (literally, the breeches-maker), a reference to his painting of loincloths and clothes onto figures. Interestingly, the nudes painted on the ceiling were not censored; the nudes on the altar wall created a problem because they challenged church authority despite the theological accuracy of the scene, which entailed people being resurrected into their idealized bodies as Christ judged them. The miracle of transubstantiation occurred at the altar below The Last Judgment—was it proper to have so much flesh, so many buttocks, and complicated poses in a scene that glorified miraculous resurrection and divine judgment, and in a space reserved for the leaders of the Church?

The years bracketing the controversy of Michelangelo’s Last Judgment (1541 and 1565) are important for understanding why the painting was met with such disdain. All those nude bodies seemed to ignore the increased calls for art that could be easy to read and educational, especially after the decrees that came out of the Council of Trent.

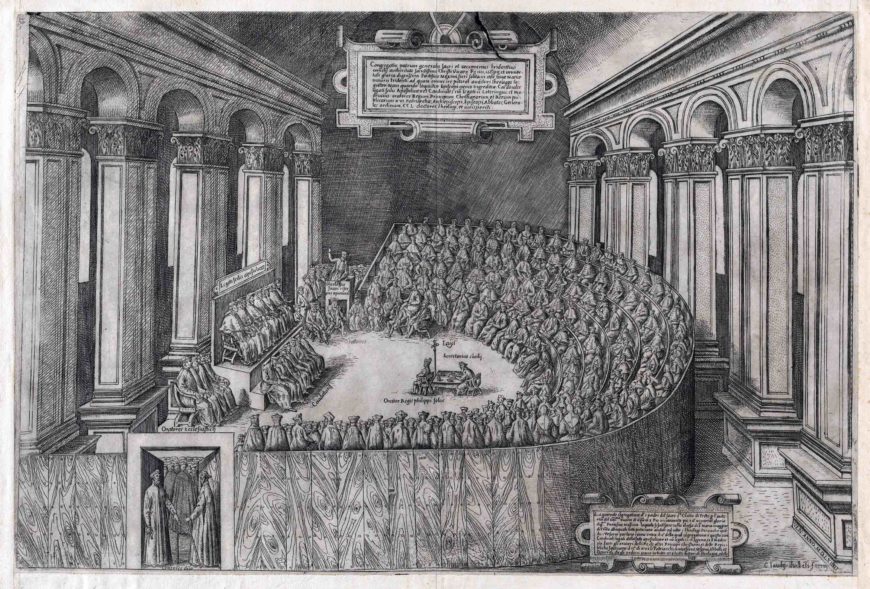

Council of Trent, 1565, in the Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae, etching and engraving, 33.5 x 49.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The anxiety of images

The Council of Trent was a synod of the Catholic Church that started to meet in 1545 to reform the Church after repeated attacks by Protestants began in 1517. While the Council discussed all matters of Catholic doctrine, images were a focus of only the twenty-fifth and final session in 1563. As many scholars have noted, the impact of Trent on Catholicism is indisputable, and similarly on a great deal of art made after it ended; this art is sometimes called post-Tridentine art, Counter Reformation art (or even Catholic Reformation), and also late renaissance art. The art made between 1560–1600 has often been overlooked in part because it has been considered unoriginal, stifled, or even formulaic, as if the Council had actually laid out specific guidelines (it did not). Scholarly discussions about the reform of art that occurred have also often situated Rome as the center where these transformations primarily occurred at the end of the 16th century and beginning of the 17th century; these earlier arguments suggested that artists then spread this reformist art to other parts of Italy, then Europe more broadly, and eventually to places like the Americas. More recently, scholars are highlighting how what actually happened is messier and more complex, and it is clear that Rome was not the sole epicenter for reformist art.

El Greco, Burial of the Count of Orgaz, 1586–88, oil on canvas, 480 x 360 cm (Santo Tomé, Toledo, Spain)

Too often late renaissance art has been described as stilted and unremarkable, as a reaction against mannerism, or as a prologue to Baroque art (what is sometimes called “proto-Baroque”). Pick up most art history textbooks and you will read an abbreviated narrative that claims that late sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century artists such as El Greco, Caravaggio, and the Carracci were among the first to innovatively respond to decrees made at the Council of Trent—leaving decades of art (c. 1560–1590) and artists overlooked.

This essay outlines Trent’s decrees on art; other essays and videos across Smarthistory consider some examples of how artists in different areas responded to the call for a reformed visual expression of Catholic ideas. Art made in this era demonstrates the wide variety of artistic responses to calls for reform. So what exactly were Trent’s decrees on art, and how did artists in different areas respond to the call for a reformed visual expression of Catholic ideas?

Countering the Protestant Reformation and the Catholic response

The Protestant Reformation began in 1517, after Martin Luther nailed his 95 theses to a door in Wittenberg (in what is today Germany). Luther and others criticized Church practices for many reasons, among them the doctrine of transubstantiation, the crucial role of saints, and the use of images. After decades of Protestant attacks, Pope Paul III convened a council meeting in the north Italian city of Trento—what we now call the Council of Trent. Visual images were certainly not the most important matter under discussion, yet the noticeable transformations that occurred in art after Trent suggest its significant impact.

Why the Council only turned to images in the final session is likely due to Protestant iconoclasts who were actively destroying religious images in parts of northern Europe. Most of the Church members in attendance at the Council were not from these areas; it seems the discussion about the usefulness of images became a topic of concern after French delegates attended the Council in 1562. The French delegation likely raised concern over the Huguenot destruction of images in France. The session was not specific about what art should look like, but it did express that it should be decorous, educational, and clear—as the Council noted in its decrees “all lasciviousness be avoided.” It also seems to suggest that art should move viewers—in other words, encourage emotional reactions to aid Christian devotees in their atonement for their role in Christ’s sacrifice.

The Tridentine decrees about images

Given the importance of the Council and its effect on visual culture more broadly, it is useful to summarize what the Tridentine decrees actually said about images and their use. The Council expressed concern over the proper use of images, and enjoined ecclesiastics and clergy in the church to “instruct the faithful” about how to use them.

The holy Synod enjoins on all bishops, and others who sustain the office and charge of teaching, that . . . they especially instruct the faithful diligently concerning the . . . the legitimate use of images. . . .

Given the Protestant claim that Catholics used images improperly, it was important for Catholics to ensure that images were employed correctly. Protestants had charged Catholics with worshipping images of Christ, Mary, or saints as if they were present in the images themselves, and so found images problematic overall; they also found Catholic practices such as touching, kissing, and talking to images inappropriate—and almost paganistic or idolatrous.

While God’s Second Commandment prohibited the worship of religious imagery (“Thou shalt not make unto thyself any graven image, nor the likeness of anything that is in heaven above or in the earth below,” Exodus 20:4), the Church in Rome had bypassed this concern early on by asserting that images played an important educational role and they were not to be worshipped, but venerated. For example, Pope Gregory II (r. 590–604) had defended the use of images within the Church from critics, supporting the central role that images played within Catholic religious practices.

Once again in the 16th century, members at the Council doubled down on the importance of images, and refused to eliminate them—affirming that they not only instruct the faithful, but also provide important models for how to live and act. In this regard, the Council simply supported the longstanding doctrine about images that had been adopted at the Second Council of Nicaea in 787. The Council of Trent noted that “images of Christ, of the Virgin Mother of God, and of the other saints, are to be had and retained particularly in temples, and that due honor and veneration are to be given them; not that any divinity, or virtue, is believed to be in them.” Images were not to be worshipped as idols, but to help channel a devotee’s thoughts to the individual represented.

It is important to note that the Council had, in other sessions, stressed the importance of venerating saints as an act of dulia rather than latria (adoration of the highest order that can be offered to God or the Holy Trinity; it also applies to the Eucharist). Venerating the image of a saint, for example, was an act of dulia because one was not confronted with the true God, such as was wholly present in the Eucharist. The faithful should only venerate, but never worship images, because they did not contain the saint but merely represented him or her—to do so would constitute idolatry.

The Tridentine decrees also support the idea that images needed to be educational—to instruct people in matters of the faith—not distract them with flourishes and artistic delights. As the Council emphasized, images were to help the faithful learn how to model themselves on the holy figures in artworks, and to “be excited to adore and love God, and to cultivate piety.” If anyone used images differently, the council decreed that they should be anathema. If images included false doctrine or unorthodox subject matter, this was dangerous because it could lead the uneducated—those who were believed not know any better—astray and lead them to false beliefs. Most people at this time were illiterate, so the educational role of images was of paramount importance for teaching the Catholic faithful—a role that was especially significant as the Church expanded its reach with conquests, colonialism, and evangelization beyond Europe.

Agnolo di Cosimo Bronzino, An Allegory with Venus and Cupid, c. 1545, oil on panel, 146.1 x 116.2cm (National Gallery, London)

One of the final points made in the Tridentine decrees (which, you will recall, were vague on what art should look like specifically) has been interpreted as an attack on mannerist art (which is itself almost impossible for scholars to define today because it encompasses such a broad range of forms and artists). The decree states that

every superstition shall be removed, all filthy lucre be abolished; finally, all lasciviousness be avoided; in such wise that figures shall not be painted or adorned with a beauty exciting to lust; nor the celebration of the saints, and the visitation of relics be by any perverted into revellings and drunkenness; as if festivals are celebrated to the honor of the saints by luxury and wantonness.

Put another way, art should not be erotic or frivolous, and it should not perplex viewers (a case could be made that paintings like Bronzino’s An Allegory of Venus and Cupid did just this with its focus on nudity and complex poses that make it challenging to understand visually). Art should not encourage people to sin—in other words, images should not cause one to drink too much nor to lust too much. Images must be decorous.

Bernardo Bitti was an Italian Jesuit who had immigrated to the viceroyalty of Peru in 1575, bringing with him the reformist attitude common among many artists after Trent. Bernardo Bitti, Coronation of the Virgin, 1575–80, Church of San Pedro, Lima, Peru, tempera (public domain)

The reach of Trent

Provided that art follows these decrees, the council emphasized that art played an important role in helping the faithful to learn, and to encourage pious reflection and contrition. The importance of the Tridentine decrees for the Catholic Church is indicated by the many times, and in many different places in the global Catholic landscape, that they were reaffirmed, such as in the Spanish viceroyalties in the Americas (which were established in the sixteenth century). Across the Atlantic, the Tridentine decrees, for example, impacted artists like Bernardo Bitti (in the viceroyalty of Peru) and Sebastián López de Arteaga (in the viceroyalty of New Spain), each of whom found creative ways to respond to the call for a reformed art, and attesting to the multiplicity of visual forms that post-Tridentine art could take. Post-Tridentine art has no single style. The important and long-lasting effect of the Tridentine decrees is indicated by eighteenth-century church councils that once again reaffirmed them.

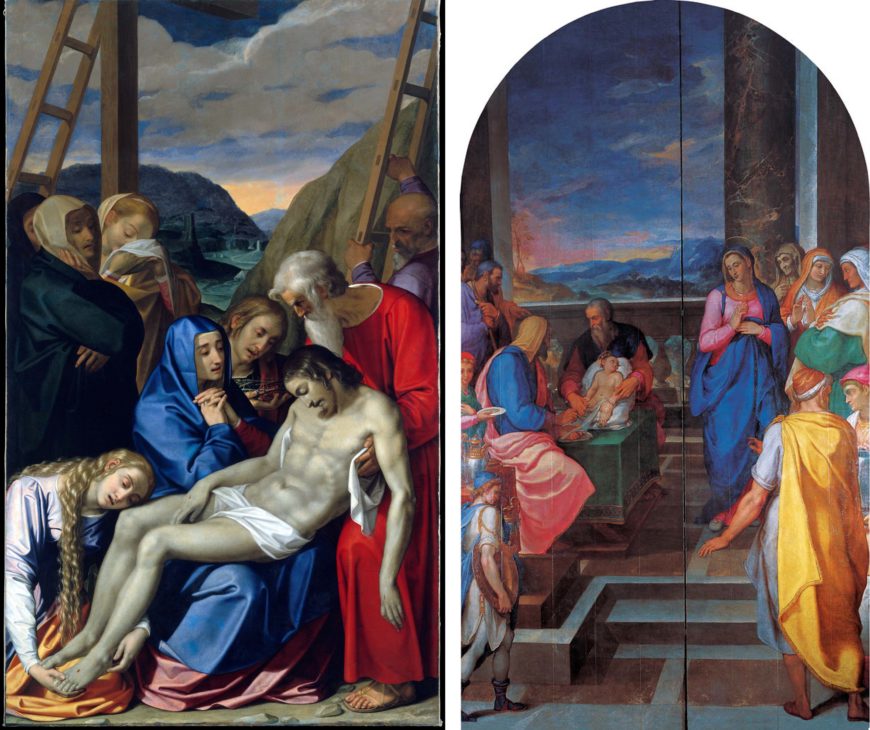

Most the art created in the 1580s and 90s for the Jesuit order’s main church, Il Gesù, has been removed from its original location in the space; some of it is has also been destroyed. Left: Scipione Pulzone, Lamentation, 1593, oil on canvas, originally for the chapel of the Passion of Christ in the church of the Gesù, Rome; 289.6 x 172.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art); right: Girolamo Muziano, Circumcision, 1587–89, originally the high altar of the church of the Gesù, Rome, but moved later

While the reformist approach to art was felt across Catholic Christendom, the form that it took could differ. Scipione Pulzone’s Lamentation (originally in the Passion chapel on the right of Il Gesù) is a simplified scene of mourners around Christ’s body after its removal from the cross, each figure painted clearly. Bright colors fill the scene, and the artist has removed extraneous details. Likewise, Girolamo Muziano’s massive Circumcision of Christ—the original high altarpiece for Il Gesù—has an easily readable composition and a rich color palette to draw viewers into the scene.

This painting of the Piedad is one of many that Luis de Morales produced in the 1570s and 80s—this was a popular subject among his patrons, as was the manner in which Morales painted it. Luis de Morales, Piedad, c. 1560–70, oil on panel (Louvre Museum)

In contrast, a stark, dramatic painting of a Spanish Piedad from later in the 16th century shows Mary cradling her dead son in her arms, his body tenderly held up. Blood streams down his arms into his hands. A few rocks, some grass, and the bottom of the cross rising behind the figures are the only motifs that the artist, Luis de Morales, has included to help us to identify the scene as the moment after Christ’s removal from the Cross. Morales has painted the moment in a straightforward way in keeping with Trent’s rulings, and it was one of many that Morales painted of this scene in the 1570s and 80s, attesting to the popularity of the way he painted this emotionally affecting scene.

Paolo Veronese, Feast in the House of Levi, 1573, oil on canvas, 18′ 3″ x 42′ (Accademia, Venice, Italy)

Other artists—including Titian and Michelangelo—would be criticized for creating images that did not seem to accord with the Tridentine decrees. A famous trial involving the Venetian painter Veronese resulted in the artist having to modify his painting of the Last Supper to a Feast in the House of Levi after it was determined that the painting was indecorous and difficult to follow. This is perhaps summed up best in a question asked of Veronese at his trial: “Do you think it is appropriate that the Last Supper of Our Lord includes jesters, drunks, Germans, people of short stature, and the like?”

Notes:

[1] Lilian H. Zirpolo, Michelangelo: A Reference Guide to His Life and Works (Rowman & Littlefield, 2020), p. 24.

Additional resources:

The Council of Trent, 25th session in its entirety

Andrew R. Casper, Art and the Religious Image in El Greco’s Italy (Penn State University Press, 2014)

Gauvin A. Bailey, Between Renaissance and Baroque: Jesuit Art in Rome, 1565–1610 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2003)

Gauvin Bailey, “‘Le style jésuite n’existe pas’: Jesuit Corporate Culture and the Visual Arts,” in The Jesuits: Cultures, Sciences, and the Arts, 1540–1773, ed. John W. O’Malley (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1992), pp. 39–44

Marcia B. Hall and Tracy E. Cooper, eds., The Sensuous in the Counter-Reformation Church (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013)

Lauren G. Kilroy-Ewbank, Holy Organ Or Unholy Idol? The Sacred Heart in the Art, Religion, and Politics of New Spain (Leiden: Brill, 2018)

Lauren G. Kilroy-Ewbank, “To Weep with Mary and Mourn for Christ: Luis de Morales and the Emotional Community of Badajoz, Spain” in Art, Emotions, and Religion in the Transatlantic World, 1500–1800, ed. Lauren G. Kilroy-Ewbank and Heather Graham, pp. 201–244 (Leiden: Brill, forthcoming 2021)

Jesse Locker, ed., Art and Reform in the Late Renaissance: After Trent (London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2019)

Rebecca J. Long, ed., El Greco: Ambition & Defiance (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2020)

John Marciari, “Girolamo Muziano, Scipione Pulzone, and the First Generation of Jesuit Art,” Journal of Jesuit Studies 6 (2019): pp. 196–212

John W. O’Malley, “The Jesuits and the Arts in the Tridentine Era,” Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review 104, no. 416 (2015): pp. 481–93

John W. O’Malley, Trent: What Happened at the Council (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2013)

Steven F. Ostrow, Art and spirituality in Counter-Reformation Rome : the Sistine and Pauline chapels in S. Maria Maggiore (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996)

Alain Saint-Saëns, Art and Faith in Tridentine Spain, 1545–1690 (Austria: P. Lang, 1995)

Ian Verstegen, Federico Barocci and the Oratorians: Corporate Patronage and Style in the Counter-Reformation, Early Modern Studies 14 (Kirksville, MO: Truman State University Press, 2015)