A hooded shirt, frayed jeans, and sneakers: these are the clothes that contemporary artist Kehinde Wiley uses to reimagine the famous ancient sculpture known as the Dying Gaul. The ancient sculpture shows a Celtic soldier succumbing to death. Wiley’s sculpture presents a modern Black man in the same pose to prompt viewers to reflect on empathy and violence in art. Following his critique, we should take a closer look at the ancient sculpture of the Dying Gaul. The original statue’s complicated politics have been forgotten during its long journey from antiquity to becoming a much-copied masterpiece in the modern world.

Dying Gaul, Roman marble copy (1st or 2nd century C.E.) of a Greek sculpture (c. 220 B.C.E), found in Rome in the early 1600s, 93 x 89 x 186.5 cm (Musei Capitolini, Rome; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Wiley is one of many artists who have studied the Dying Gaul. As early as 1683, Gérard Audran illustrated the statue in a book about human proportions, and Giovanni Panini even showed artists drawing the Dying Gaul in the foreground of his monumental painting Ancient Rome from 1757. Full-size plaster replicas of the sculpture are held by museums around the world and have been used to teach students appreciation for the classical art of the ancient Mediterranean. In art history textbooks, the Dying Gaul is often illustrated as an ideal example of ancient Greek and Roman art. These repeated references give the sculpture a central place in the art historical canon.

Yet, the Dying Gaul is based on an ancient ethnic stereotype that combines objects and physical features to portray Celts as both outsiders and uncivilized barbarians. This stereotype was developed by the Greeks who feared Celtic invasions even while hiring Celtic men as mercenaries and trading with Celtic communities across long-distance networks. The Romans later used the stereotype to commemorate their own victories over Celtic armies.

Left: Celtic sculpture of a warrior wearing a lobed headdress (known as the Glauberg warrior), 5th century B.C.E., stone, 1.86 m, 230 kg, excavated from an aristocratic tomb complex in 1994 (World of the Celts Museum, Glauberg); right: Celtic sculpture of a bearded man wearing a torc necklace (known as the Trémuson head), 1st century B.C.E., stone, 40 cm, excavated from an aristocratic villa complex in 2019 (Trémuson, France)

Celtic sculptures like the Glauberg warrior (above left) and Trémuson head (above right) reveal how Celts saw themselves. Such works have received far less attention than the Dying Gaul in part due to aesthetic biases that favor naturalism over more abstract representations. If you look closely at the sculpted arms, you will see that those on the Glauberg warrior resemble cylinders, while those on the Dying Gaul have defined musculature. High naturalism contributes to the Dying Gaul’s enduring fame, but does not necessarily make the work more important or more truthful.

In order to understand the Dying Gaul’s legacy for modern artists and viewers, its stereotyping of Celtic peoples needs to be explored and balanced with images made by the Celts themselves. Doing so reveals the limitations of the canon and the consequences of exclusion.

Dying Gaul (detail), Roman marble copy (1st or 2nd century C.E.) of a Greek sculpture (c. 220 B.C.E), found in Rome in the early 1600s, 93 x 89 x 186.5 cm (Musei Capitolini, Rome; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The stereotype: origins and legacy

Greeks in the eastern Mediterranean developed the stereotype for Celtic peoples in the fourth and third centuries B.C.E., when Celts were migrating from their homelands and successfully claiming new territory in northern Italy (ancient Gallia Cisalpina) and central Turkey (ancient Galatia). Later, as Rome’s empire simultaneously expanded, Roman leaders found the stereotype useful for their own monuments commemorating victories over Celts.

The sculpture of the Dying Gaul itself is thought to be a Roman marble copy of a Greek statue (now lost) from the eastern Mediterranean. [1] The Greek statue was created around 220 B.C.E. The Roman version dates to the first century B.C.E. By that time, nearly all Celtic territories had been annexed by Rome. Ireland and much of Scotland ultimately escaped Roman conquest, which is one reason why Celtic cultures persisted in those regions.

Seeing the stereotype

To see the stereotype, we need to look closely at the Dying Gaul’s belongings, body, and pose. [2]

Celtic sculpture of a man with mustache and torc, c. 200 B.C.E., stone, 23.4 cm high, found at Mšecké Žehrovice in 1943 (National Museum, Prague; photo: Zde, CC BY-SA 4.0)

A distinctive open necklace called a torc establishes the warrior’s Celtic identity. Similar artifacts appear in Celtic self-representations, such as the Trémuson head and the damaged warrior statues from Entremont.

Celtic torc and coins found at Tayac, c. 100 B.C.E., gold, part of a buried treasure found in 1893 (Musée d’Aquitaine, Bordeaux)

Torcs also survive in the Celtic lands of ancient Europe. The torc found at Tayac even has a twisting shape similar to the one worn by the Dying Gaul. Romans targeted these necklaces for looting during military campaigns: to have seized one from an opponent was considered a sign of valor. [3] Torcs even appeared on Roman coins to symbolize Celtic defeat. Greek and Roman men did not wear such prominent necklaces, so this jewelry was part of the “othering” of the Celtic soldier.

The mustache also distinguished the Dying Gaul as an outsider to Greek and Roman men who grew beards or were clean-shaven, but did not favor mustaches alone. In Celtic sculptures, men could appear fully bearded, fully clean-shaven, or with a mustache, so this feature may have had some basis in reality.

The hairstyle and face of the Dying Gaul are more difficult to judge for two reasons. First, we do not have the full ancient statue: earlier restorers replaced the missing nose and trimmed the broken tips of the hair to improve the appearance for display. Second, the ancient representation was filtered through Greek and Roman ideas about Celtic bodies and hairstyling. Diodorus Siculus, for example, recorded this impression of Celtic men:

They are tall in body, with rippling muscles and white skin, and their hair is blond, not only naturally so, but they are also accustomed to use artificial means to enhance its natural color. For they are always washing it in lime-water, and they pull it back from the forehead to the top of the head and back to the nape of the neck, so they look like Satyrs and Pans; since this treatment of their hair makes makes it so heavy and coarse that it differs not at all from horses’ manes.Diodorus Siculus, Historical Library, 5.28.1-2

Dying Gaul (detail), Roman marble copy (1st or 2nd century C.E.) of a Greek sculpture (c. 220 B.C.E), found in Rome in the early 1600s, 93 x 89 x 186.5 cm (Musei Capitolini, Rome; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Scholars have noted that the Dying Gaul’s face has parallels in Greek and Roman images of satyrs (who were half human, half animal). For example, the Barberini Faun shares with the Dying Gaul a furrowed brow and v-shaped face crowned with wavy hair. (The Barberini Faun also has a tail and pointed ears, which the Dying Gaul lacks.) The Celts’ own images reveal a range of hairstyles and faces, but none seems intended to liken men to animals. [4]

The Dying Gaul’s nudity and wound are more enigmatic and have no known parallels in Celtic art. In Greek and Roman art, the nudity of a perfectly toned male body could reveal heroism or eroticism. Greek and Roman sources also record that Celtic leaders sometimes went into battle naked as an intimidation tactic, so the Dying Gaul’s lack of clothing may have had an historical association. [5]

Dying Gaul (detail), Roman marble copy (1st or 2nd century C.E.) of a Greek sculpture (c. 220 B.C.E), found in Rome in the early 1600s, 93 x 89 x 186.5 cm (Musei Capitolini, Rome; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Issued by Julius Caesar, the coin depicts a trophy installation made of seized carnykes (Celtic trumpets with animal heads), shields, a torc, helmet, and armor. Beneath are a clothed woman and a nude, bearded man with bound hands, and the worn letters of Caesar’s name. Roman denarius, 46 B.C.E. silver, 1.78 cm diameter (American Numismatic Society, New York)

Nudity reveals the sword wound on the Dying Gaul’s chest. The dripping blood would have been even more vivid when the sculpture was painted. The wound’s location on the front of the body indicates that the Celt displayed the heroism of meeting his foe face-to-face rather than turning and running away. Yet the injury also makes clear that he was defeated by his opponent. Modern viewers often respond to his defeat with empathy, but we do not know what ancient viewers thought.

As the soldier succumbs to his wound, his pose is tensely balanced. One knee points upward, while the torso and head tilt downward to foreshadow his fall. This pose makes the nude, dying body vulnerable to our gaze, while also locking the man into a defeated fate. If we survey Greek and Roman representations of Celtic soldiers, we find that they are most often shown dying or captured, with their hands bound, beneath displays of their seized weapons. Movement is limited to running away, as Celtic soldiers are shown doing in a set of terracotta sculptures from Civitalba.

Celts naturally did not depict their own defeat. In fact they won major victories against Greek and Roman armies, and even sacked the city of Rome in 387 B.C.E. The stereotype obscures this much more complicated history.

Celtic patterned disk, 2nd century B.C.E., bronze, 20 cm diameter, excavated from a tomb at Roissy in 1999 (Musée d’Archéologie Nationale, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, photo: BastienM, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Celtic perspectives

Celtic points of view can be difficult to recover. Ancient Celts prioritized spoken transmission of their beliefs and histories, so they left few texts to consult. In addition, most Celtic peoples favored intricate patterns in their art, rather than realistic portrayals of people or events. A few communities, however, featured soldiers in their art, and these experiments help us understand heroism from a Celtic point of view.

Celtic coin with a head and the name Dubnocou (front) and a warrior and the name Dubnoreix (back), 50s B.C.E., silver, 1.4 cm diameter, minted by the Aeduan people of Bibracte, France (Bibliothèque Nationale, Cabinet des Médailles, Paris). The warrior (right) wears a helmet and armor and has a sword hanging from his right hip. In his right hand, he holds a military standard in the shape of a boar and an animal-headed trumpet called a carnyx. In his left hand, he holds the severed head of an enemy. The accompanying letters give an alternative spelling of Dumnorix, a well-known Aeduan leader mentioned in Julius Caesar, Gallic War, 1.3, 1.9, 1.18-20, 5.6-7.

Heroism on Celtic coins

Celtic coin with the name Viipotal and an image of a Celtic warrior on the back (shown here), 50s B.C.E., silver, 1.5 cm diameter, possibly minted by the Pictones people of Poitiers, France (Bibliothèque Nationale, Cabinet des Médailles, Paris). This coin dates to the era of the Roman invasion led by Julius Caesar

Celtic coins typically omitted words and featured images that were highly abstract. [6] In the first century B.C.E., however, the names of Celtic leaders appeared on a number of coins, sometimes accompanied by warrior imagery. At the time, the region’s peoples were negotiating political alliances among themselves and responding to repeated Roman invasions. The coins had a practical purpose of sealing alliances and paying soldiers.

One slightly worn coin depicts a Celtic soldier standing and facing the viewer. The warrior wears a helmet, armor, and a belt over a short tunic. His left hand holds a long oval shield. His right hand holds a sculpted boar (the wild pig’s snout faces down). Behind the soldier’s right wrist is an upright spear. Compared to the Dying Gaul, this warrior stands ready for battle, wears armor to protect his body from enemy weapons, and has his own weapon close at hand.

The boar sculpture is a military standard. Boars were important symbols of ferocity in the region’s culture, and bronze military standards like the one on the coin have been excavated in France. Whereas the coin’s soldier brandishes a well-crafted animal symbol as a sign of power, the Dying Gaul‘s soldier is made to resemble a half-wild creature himself (given that his hair resembles a satyr’s).

The name Viipotal curves around the upper right of the coin’s edge. [7] Viipotal is not known from any other textual sources, so we do not know who he was or why an image of a soldier appeared next to his name. Nonetheless, coins like Viipotal’s allow us to speak of particular Celts, rather than anonymous stereotypes like the Dying Gaul.

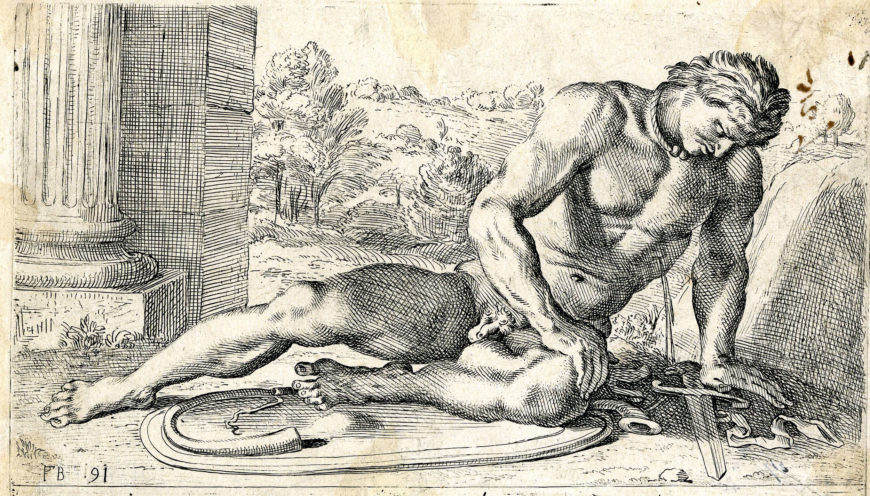

Perrier’s etching reimagines the statue as a human combatant with a bleeding chest wound. The pose is reversed in the print, but would have been correct on the original etching plate. François Perrier, from the series Segmenta nobilium signorum et statuarum, 1638, etching, 13.4 x 23.3 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Incompatible afterlives

Of all these images of Celtic soldiers, the Dying Gaul is by far the best known. Since the sculpture was rediscovered in the early 1600s, its fame has been spread worldwide by paintings, prints, photographs, and replicas. [8] The statue itself is so highly esteemed that it has been displayed abroad twice. In 1796, Napoleon had it seized and transported to Paris (it was returned in 1816). In 2013–14, Italy loaned the statue to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. in order to promote Italian culture.

The Celtic coins and statues are far less famous. They have been treated as historical evidence, rather than canonical works worthy of recreation and display abroad.

Dying Gaul exhibited at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Roman marble copy (1st or 2nd century C.E.) of a Greek sculpture (c. 220 B.C.E), found in Rome in the early 1600s, 93 x 89 x 186.5 cm (Musei Capitolini, Rome; photo: Rob Shelley)

Consequences for the canon

The Dying Gaul combines admiration (Celts meet death with courage), insult (Celts are animalistic), truth (Celts wear torcs), and fiction (Celts always lose). Today we more often see such “enemies of the moment” portrayed in films, but villains in spy movies vary in ethnicity from decade to decade and from nation to nation. The difficulty with the Dying Gaul is that it stereotypes a momentary enemy in a work that has achieved lasting global fame.

The Dying Gaul remains canonical because we continue to engage with it. Kehinde Wiley and other artists have good reasons for copying past creations, and art historians develop expertise so as to recognize and interpret their allusions. Yet repeated references can reinforce the importance of biased works while still marginalizing alternative points of view. The Celts deserve a place in this conversation.

Notes:

[1] The Dying Gaul is not the only version of this statue from antiquity. A fragmentary torso in the same pose is held by the Skulpturensammlung, Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen, Dresden (inventory number HM 154). A smaller version with a mirrored pose also survives and shows a nude soldier wearing a helmet, with a circular spear wound through the front and back of his torso (inventory number 6015, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples, Italy).

[2] After the statue was rediscovered in Rome in the early 1600s, restorations replaced missing areas, including the figure’s toes, left knee, right arm, and nose, as well as the sword on the ground. The head shows signs of multiple reattachments, and restorers also trimmed the fragmented ends of the hair. The shield and trumpet are original to the statue, and they match Celtic evidence in the archaeological record.

[3] The Roman military even created and distributed its own torcs as general awards for courage. These Roman military torcs were typically worn on the chest like a badge, as demonstrated by the funerary portrait of the Roman centurion Marcus Caelius (Xanten, Germany, 9 C.E.; C.I.L. 13, 1848; Rheinisches Landesmuseum, Bonn, Germany).

[4] One exception is the Celtic Euffeigneix Pillar (first century B.C.E.), which has a human head, a ponytail, a torc, an image of a boar on the torso, and animal eyes on the sides. Many Celtic communities revered boars for their ferocity, so this melding of human and animal elements would have been complimentary (Inventory number MAN 78243, Musée d’Archéologie Nationale, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France).

[5] Polybius (Histories, 2.28-29) mentions this strategy at the Battle of Telamon, Italy, fought by the Celts and the Romans in 225 B.C.E.

[6] Celtic communities began minting coins around 300 B.C.E. and took inspiration from the coins of the Greeks and Romans with whom they traded and for whom they worked as mercenaries.

[7] The name is spelled out in the Roman alphabet that the Celts sometimes used to record the sounds of their names even before their territories were claimed by the Roman Empire.

[8] In the 19th century, scholars recognized that the torc and shield could be matched with Celtic artifacts. Before then, the statue was called the “Dying Gladiator,” and many early illustrations still have this title.

Additional resources

Holger Baitinger and Bernhard Pinsker, eds., Das Rätsel der Kelten vom Glauberg Glaube-Mythos-Wirklichkeit (Stuttgart: Theiss, 2002).

Kimberly Cassibry, “The Tyranny of the Dying Gaul: Confronting an Ethnic Stereotype in Ancient Art,” Art Bulletin 99.2 (2017): pp. 6–40.

Filippo Coarelli, ed., La gloria dei vinti: Pergamo, Atene, Roma (Milan: Electa, 2014).

Julia Farley and Fraser Hunter, Celts: Art and Identity (London: British Museum Press, 2015).

Julia Genechesi and Lionel Pernet, eds., Les Celtes et la monnaie: Des Grecs aux surréalistes (Gollion: Infolio, 2017).

Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny, Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Classical Sculpture 1500–1900 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), pp. 224–27.

Benjamin Girard, ed., Au fil de l’épée: Armes et guerriers en pays celte Méditerranéen (Nîmes: Musée Archéologique, 2013).

John Marszal, “Ubiquitous Barbarians: Representations of the Gauls at Pergamon and Elsewhere,” in From Pergamon to Sperlonga: Sculpture and Context, edited by Nancy Thomson de Grummond and Brunilde Sismondo Ridgway (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), pp. 191–234 (figures 69–85).

Kehinde Wiley, An Archaeology of Silence (Paris: Galerie Templon, 2022).

Sabatino Moscati et al., eds., The Celts (New York: Rizzoli, 1991).

Felix Müller, Art of the Celts: 700 BC to AD 700 (Brussels: Mercatorfonds, 2009).

Robin Osborne, “How the Gauls Broke the Frame: The Political and Theological Impact of Taking Battle Scenes off Greek Temples,” in The Frame in Classical Art, edited by Verity Platt and Michael Squire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), pp. 425–56.

Lionel Pernet, “Les représentations d’armes celtiques sur les monuments de victoire aux époques hellénistique et romaine: de la statue de l’Étolie vainqueur à l’arc d’Orange. Origine et mutation d’un stéréotype,” in Contacts de cultures, constructions identitaires et stéréotypes dans l’espace méditerranéen antique, edited by Hélène Ménard and Rosa Plana-Mallart (Montpellier: Montpellier Presses Universitaires de la Méditerranée, 2013), pp. 21–35.

Michel Py, La sculpture gauloise méridionale (Paris: Errance, 2011).

Andrew Stewart, Art in the Hellenistic World: An Introduction (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014), pp. 75–83.