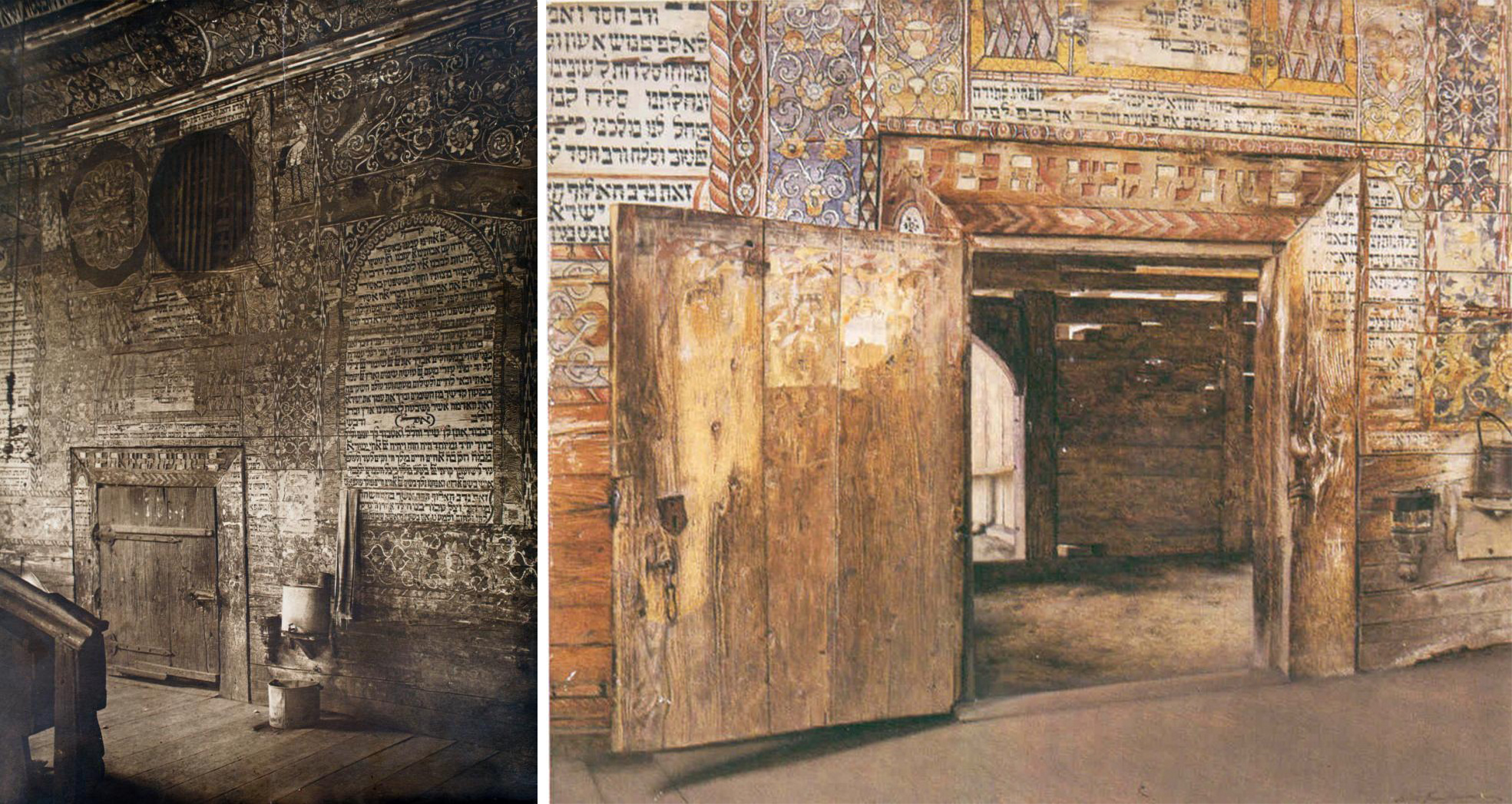

Left: Western wall and door, Gwoździec synagogue, mid-17th century, Ukraine. Photographer: Alois Breyer, 1910–13 (The Center for Jewish Art); right: Isidor Kaufmann, Portal of the Rabbi, 1898, oil on canvas (Magyar Nemzeti Galeria, Budapest)

In the late 1890s, Viennese Jewish painter, Isidor Kaufmann traveled throughout the territory of modern-day Ukraine to research and document wooden synagogues and their richly painted interiors. Among the many communities and synagogues that he visited, he lingered in the Gwoździec synagogue, which he later painted upon returning to his Vienna studio. During World War I, the Gwoździec synagogue was damaged, and, along with nearly all of the two-hundred (known) painted wooden synagogues across Eastern Europe, was ultimately destroyed by the Nazis during World War II. Isidor Kaufmann’s painting, and documentation produced before 1939 by architects, art historians, and ethnographers, constitute the only surviving testimonies of the synagogue’s remarkable architecture and the dense and colorful wall paintings that adorned its interior. With their devastating destruction, this documentation of the Gwoździec synagogue provides a glimpse of this unique tradition of painted synagogues popularized among 17th- and 18th-century Ashkenazi Jewish communities.

Gwoździec and the “golden age” of the shtetl

Today, the town of Gwoździec is located in southern Ukraine. However, in the 1640s, when the Jewish community built their synagogue, Gwoździec was part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (a federation of the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania). At that time, as one of the largest states in Europe, Jews were invited to help settle the region, bringing a successful trading and craft economy with them. In Gwoździec and in towns across the Commonwealth, from modern-day Ukraine-Jews built more than two hundred richly painted wooden synagogues, each a centerpiece in its community.

Gwoździec Synagogue, mid-17th century, Ukraine. Photographed by Alois Breyer, 1910–13. (The Center for Jewish Art)

Gwoździec is often described as a shtetl, which means “small town” in Yiddish. This term may conjure up images from the play and film Fiddler on the Roof. We imagine Tevye the milkman, his family, and his neighbors, living in poverty and suffering from persecution, pogroms, and displacement. While this is in fact an appropriate description of many 19th- and early 20th-century Eastern European Jewish communities, it obscures a more prosperous and relatively stable period of Jewish life in Eastern Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries. In the 1640s, when the Jewish community of Gwoździec built their synagogue, they were an affluent community, able to afford the highest standards of construction and craftsmanship. Despite the devastation of the Jewish community during the Chmielnicki massacres in 1648, by 1731, when the congregation remodeled their synagogue, they were once again a prosperous and thriving community. The synagogue’s architecture and the paintings on its walls and ceiling testify to this period of Jewish wealth and stability in the region.

Left: Manor house, Ożarów, Poland, 17th century (Morgoth, CCO 1.0); right: Church of St. Michael in Uzhok, Ukraine, 1745. Photograph, 1919 (Library of Congress)

Jewish architecture and painting in a regional style

Jewish law does not define a single style for synagogue architecture. As a result synagogues around the world have adopted local styles and adapted them to suit Jewish worship. The Gwoździec synagogue, and hundreds of other wooden synagogues across the region, reflect this adaptation of local Polish-Ukrainian architectural styles. Built with squat, stacked-log walls, surmounted by a mountainous multi-tiered roof, and ornamental decorative woodwork, the synagogue resembled local wooden architecture, including manor houses of the nobility and nearby churches. Despite these similarities, the Jewish community distinguished their synagogue from other town buildings through its massive tiered, sloping roof, which would have dominated the landscape of the town. Although local laws restricted Jews from building their synagogues higher than the steeple (tower) of the church, they did not delimit the height of the synagogue in relation to the church’s rooftop. As a result, wooden synagogues often towered over the rooftops of nearby churches and government buildings. In their massive scale and dramatic roofs, they created a sense of weightiness and immobility, marking the hope for a permanent dwelling for the Jewish community.

The architecture of the Gwoździec Synagogue

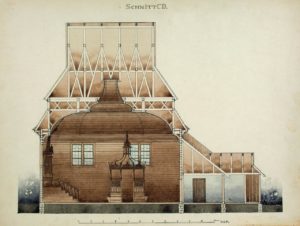

Longitudinal section drawing, Gwoździec Synagogue, mid-17th century, Ukraine (The Center for Jewish Art)

When the synagogue was first built in the 1640s, it was constructed as a single large hall with a barrel-vaulted ceiling. However, in the 1720s, the congregation modified the existing ceiling by cutting a hole in its center to introduce a complex, and undulating dome structure with both concave and convex forms, creating a towering cupola to crown their space of worship. This dramatic ceiling created an interior space reminiscent of contemporaneous tents, whose symbolic meaning will be discussed below, which was promptly imitated in synagogue constructions throughout the region.

On its interior, the synagogue featured two characteristic elements of Jewish religious architecture—a bema (a raised platform from which the Torah is read during services), and a Torah ark, which encloses and protects the Torah when it is not in use. In the Gwoździec sanctuary, as in other Ashkenazi congregations, the bema is centrally located. The highly ornamental Torah ark, an elaborate architectural element of massive size and ornamentation, dominated the eastern wall, indicating the direction of Jerusalem.

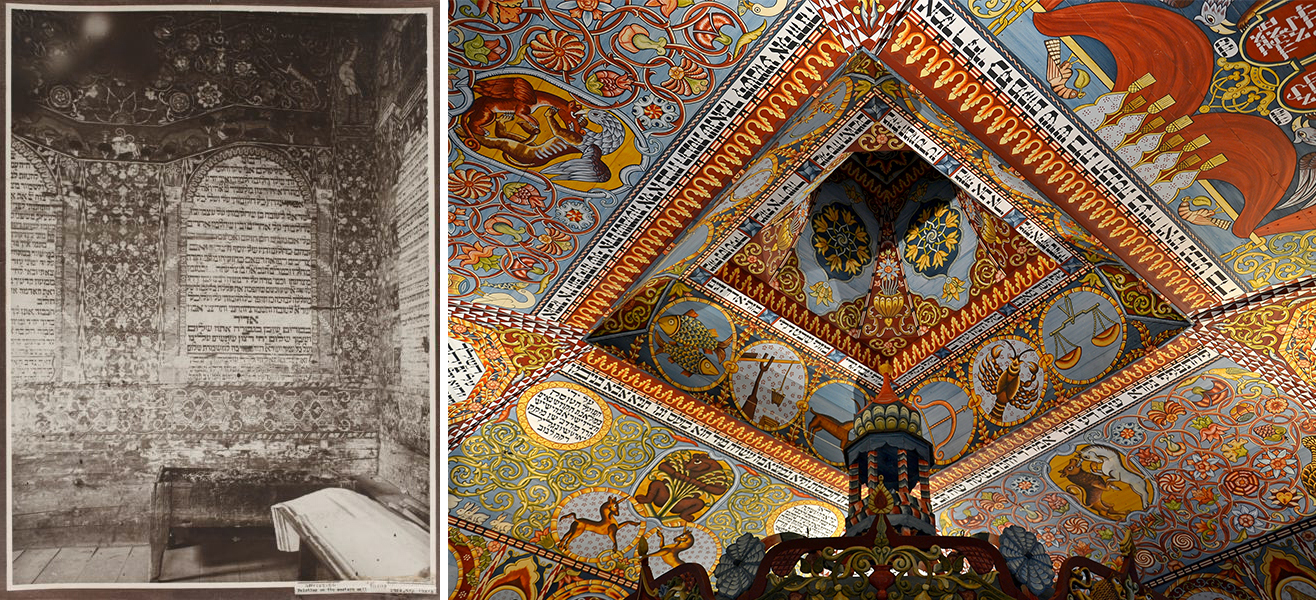

Left: Wall decoration with painted prayers, Gwoździec synagogue, mid-17th century, Ukraine. Photographed by Alois Breyer, 1910–13 (The Center for Jewish Art); right: reconstruction of Gwoździec synagogue ceiling, 2013, Handshouse Studio (Pudelek CC BY-SA 4.0)

Moreover, on its interior, the synagogue was covered from floor to ceiling in colorful imagery. The lower walls included texts of Hebrew prayers derived from the Jewish liturgy, including some of the most commonly recited prayers of the weekday and Shabbat worship services, bounded by floral and geometric patterns. In their large font and placement at eye-level, they provided a legible text to aid worshippers during prayer services and also functioned symbolically to envelop the synagogue and its congregation in perpetual prayer. In contrast, the upper portion of the walls and ceiling featured animal imagery, the twelve signs of the zodiac, and additional Hebrew texts, including the signatures of the artists—Isaac son of Rabbi Judah Leib ha-Cohen and Israel son of Mordechai from Yarychiv (a town in modern-day southern Ukraine)

Left: Israel Dov Rosenbaum, Mizrach, 1877, Pdkamen, Ukraine, paper cut (Jewish Museum); middle: Torah ark, Dubno synagogue, 1814, renovated 1878, western Ukraine (Yad Vashem Photo Collection); right: tombstone in Jewish cemetery, Sataniv, Ukraine (Roman Starchenko, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The abundant animal imagery in Gwoździec, and throughout the Eastern European painted synagogues, prompted renewed attention to a long-standing debate among rabbinic leaders about the presence of figural imagery within a Jewish house of worship. Animal figures appeared to challenge the second commandment prohibition against the creation and worship of “graven images.” Some rabbis expressed concern that the presence of such motifs could both be a distraction from devotion as well as be mistaken for idolatry (the worship of images).

The division of images within the synagogue, with animal imagery limited to the upper registers where congregants were less likely to be looking, may have partially circumvented this problem. However, the ubiquity of such images throughout all periods of Jewish artistic production, and in particular in 17th- and 18th-century Eastern European Jewish religious art—wall paintings, papercuts, Torah arks, tombstones, and ritual objects—suggests that animal, floral, and geometric motifs were ultimately deemed permissible.

Left: painted interior of the Church of St. George, Drohobych, Ukraine, 1659–60 (Bo&Ko, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: Polish folk motifs, wall paintings, parish church, Debno, Poland, 17th century (magro_kr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Worms Mahzor, Germany, 1272 (Jewish National and University Library, Jerusalem)

As with the synagogue’s architecture, the wall paintings likewise find counterparts in the painted interiors of nearby churches.

At the same time, many of the painted images—including animal and architectural motifs—draw upon a Jewish visual vocabulary already present in medieval Hebrew illuminated manuscripts from Germanic lands, such as the decoration of the Worms Mahzor, a 13th-century Hebrew manuscript completed in the German city of Würzburg.

Divine Mercy and the Tent of Heaven

The Jewish community interpreted the devastation of the 17th-century Chmielnicki massacre as a statement of divine punishment. Although the community recovered rapidly from this period of upheaval, their attitudes shifted and became more penitential, one heavily informed by Jewish mystical traditions, as they yearned for a messianic future, with the arrival of a Jewish messiah ushering in an era of global peace and harmony.

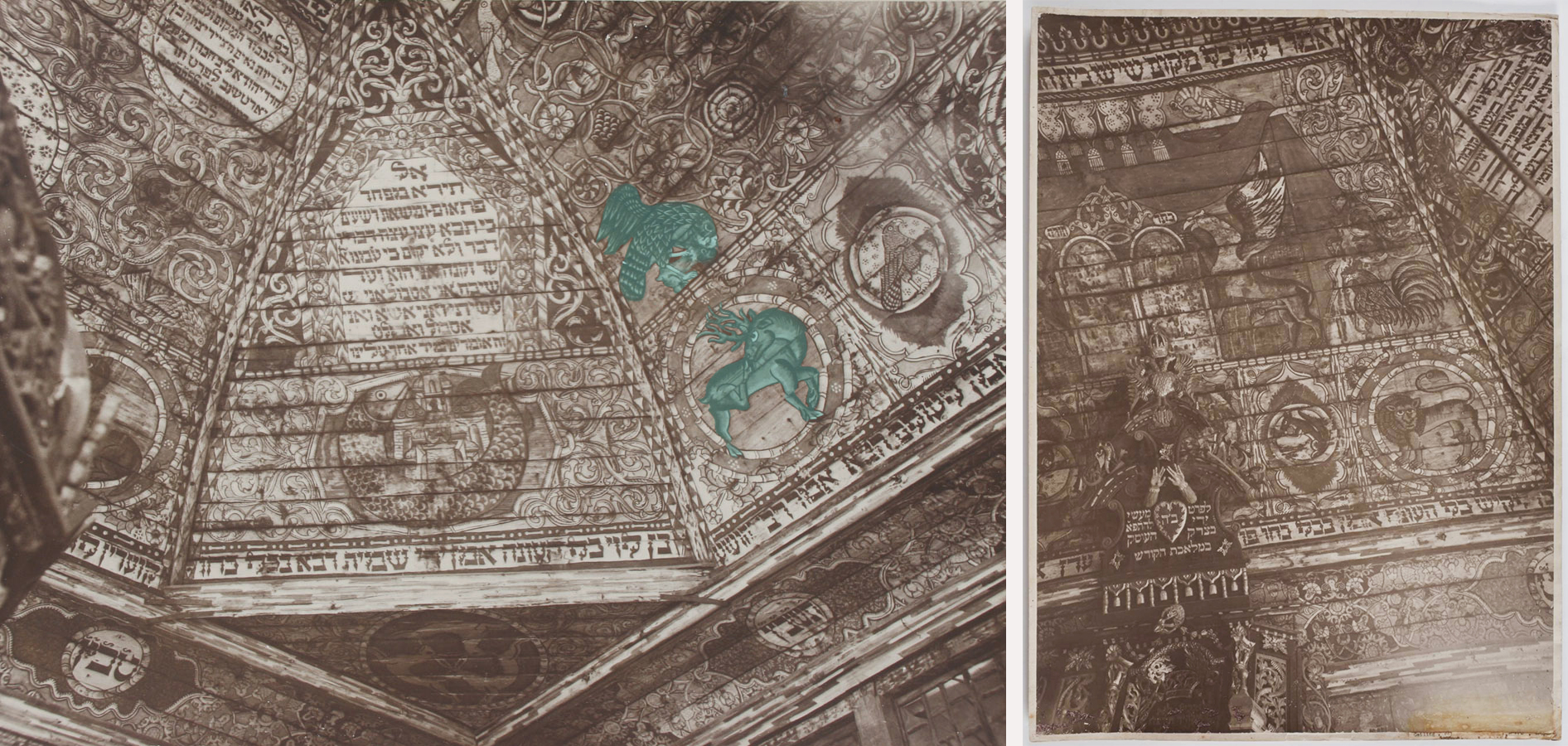

Left: Details of deer and eagle with a hare in its talons, Gwoździec synagogue ceiling, mid-17th century, Ukraine. Photographed by Alois Breyer, 1910–13 (The Center for Jewish Art); right: top of carved Torah ark on Eastern wall of Gwoździec synagogue ceiling, mid-17th century, Ukraine. Photographed by Alois Breyer, 1910–13 (The Center for Jewish Art)

This cultural and religious upheaval imbued the wall paintings with additional meaning. For example, the motif of the deer, appears in a medallion with its head turned, gazing backwards. In the Zohar, a Jewish mystical text, the deer is described as constantly running and looking back, just as God, driven away by the Israelites’ sins, looks back upon them with compassion and mercy. Such an image might have resonated with the community, hoping to be forgiven for their sins. Likewise, the image of an eagle as a predator with a small animal in its beak, appears throughout the synagogue’s painted decoration. In the aftermath of the Chmielnicki massacres, many Jewish chronicles refer to an eagle bearing exiles on its wings. It’s possible that the repetition of eagles throughout the ceiling paintings refers to the community’s collective memory of the massacre and their salvation under God. On the northern wall of the ceiling, for example, eagles with hares in their mouth flank a central image of a unicorn battling a lion. Perhaps the hares, and other prey, may also express the community’s desire for justice against their oppressors. In addition to this predatory imagery, crowned double-headed eagles also appear in two of the corners of the ceiling as well as surmounting the Torah ark. By using the form of the double-headed eagle, royal emblems of the Habsburg and Russian Empires, signifying the King’s absolute power, the artists transformed the motif into one symbolizing God’s absolute, heavenly rule, guided by both justice and mercy.

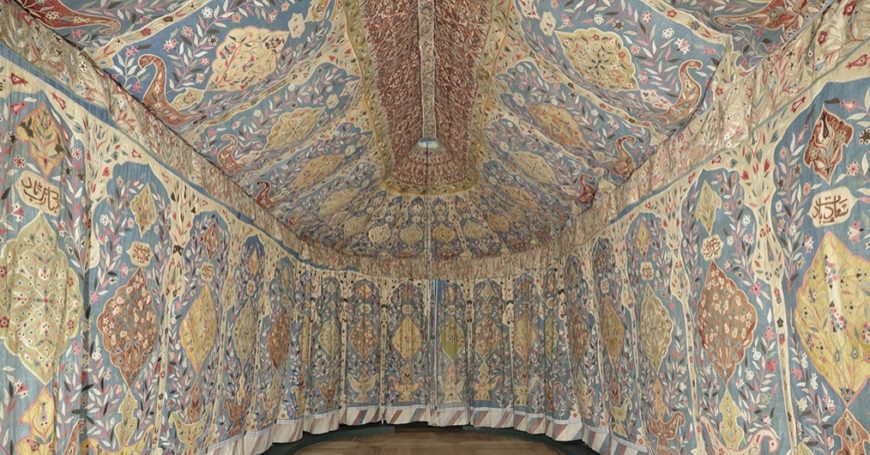

Ottoman tent, seized by King Jan III Sobieski after the siege of Vienna in 1683 (Wawel Royal Castle)

The Gwoździec synagogue’s remodeled ceiling closely resembled the form of the most recognizable tent for 18th-century Jews in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth—Ottoman royal tents. After Polish King Jan III Sobieski lent support against the 1683 Turkish siege of Vienna, he returned with Ottoman tents, which became a national symbol of Polish culture.

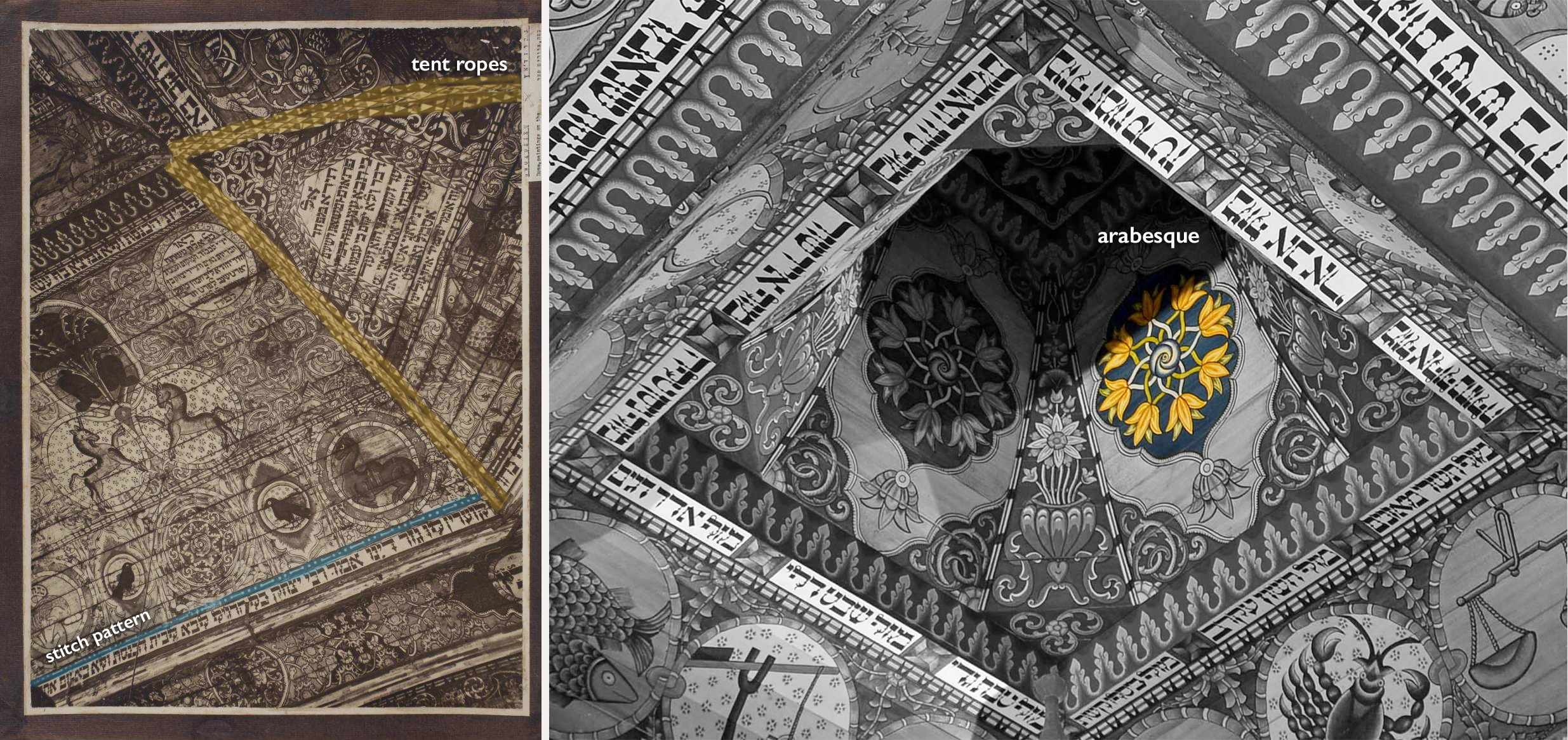

Left: Details of stitch and rope motif, Gwoździec synagogue ceiling, mid-17th century, Ukraine. Photographed by Alois Breyer, 1910–13 (The Center for Jewish Art); right: detail of arabesque motif, reconstruction of Gwoździec synagogue ceiling, 2013, Handshouse Studio (Pudelek CC BY-SA 4.0)

Looking to this familiar tent structure, the Jewish community not only imitated its form, but also its ornament, including stitch motifs painted on the ceiling where one might expect pieces of cloth to be sewn together, as well as patterns resembling ropes used to raise a tent, and arabesque motifs common in Ottoman carpets and tents circulating within the Commonwealth.

For its congregation, the painted dome of the Gwoździec synagogue symbolized the biblical tent of worship, part of the mishkan, or the ancient Jewish tabernacle, believed to have been the earthly dwelling place of God. By evoking the tabernacle, the Jewish community of Gwoździec visually transformed their synagogue into a divine space.

Destruction, memory, and preservation

German soldiers observe burning wooden synagogue in Lithuania during World War II, 1941 (Das Bundesarchiv)

Tragically, like the Gwoździec synagogue, almost all of the Eastern European painted wooden synagogues were destroyed by the Nazis in World War II. The vibrant tradition of Eastern European synagogue painting can thus only be glimpsed through late 19th- and early 20th-century documentation.

Fortunately, the Gwoździec synagogue and other painted wooden synagogues across the former territory of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth attracted the attention of several ethnographers and artists, including Isidor Kaufmann as previously mentioned, but also Alois Breyer and Szymon Zajcyzk, among others. Breyer, a Roman Catholic student of architecture, produced more than 200 photographs and architectural renderings of synagogues throughout the territories of modern-day Poland and Lithuania, which constitute the most comprehensive collection documenting eastern European synagogues to this day.

Breyer’s watercolor study of the northern section of the Gwoździec synagogue ceiling, along with Isidor Kaufmann’s painting, provide the only records of the ceiling’s original colors. In the interwar period (1919–39), Jewish photographer and art historian Zajcyzk oversaw a professional survey sponsored by the Polish state to document Eastern European wooden synagogues, producing thousands of plans, drawings, and photographs, including photographs and plans of Gwoździec. Zajcyzk himself was murdered by the Nazis in 1944, but thanks to his efforts to hide his archive during the war, many of the documents survived.

Installation of the reconstructed Gwoździec synagogue ceiling and bema in the POLIN Museum of the History of the Polish Jews, 2013, Handshouse Studio (Pudelek CC BY-SA 4.0)

Using the extensive pre-1939 documentation, in 2011–13, Handshouse Studio, a non-profit educational organization, constructed an almost full-scale recreation of the Gwoździec synagogue ceiling, roof, and bema using period materials, tools, and techniques. It is currently displayed as the centerpiece of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw, Poland. Not only does the installation preserve the memory of the lost synagogue and its 18th-century congregation, but in the process of its creation, involving over three hundred participants in educational and hands-on workshops across Poland, it created a new experience in the thousand-year history of Polish-Ukrainian Jewry.

Additional resources

Writing a History of Synagogue Architecture

Center for Jewish Art’s Catalogue of Wall Paintings in Central and East European Synagogues

Handshouse studio, Gwoździec Synagogue Reconstruction

Batsheva Goldman-Ida, “Early Modern Synagogues in Central and Eastern Europe,” Jewish Religious Architecture: From Biblical Israel to Modern Judaism, edited by Steven Fine (Leiden: Brill, 2019), pp. 184–207.

Thomas Hubka, Resplendent Synagogue: Architecture and Worship in an Eighteenth-Century Polish Community (New Hampshire: University Press of New England, 2003).

Maria Piechotka, Heaven’s Gates: Wooden Synagogues in the Territories of the Former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Kurpski i S-ka, 2004).