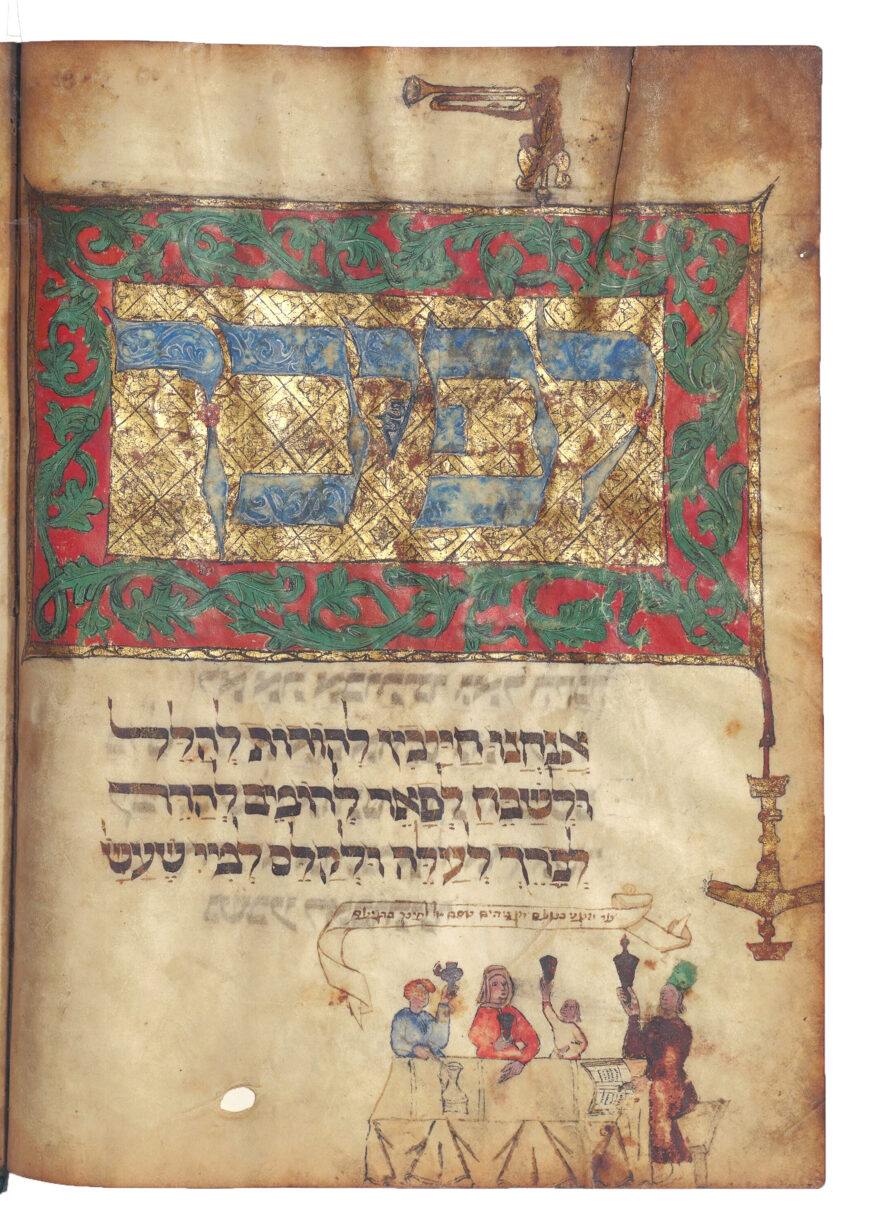

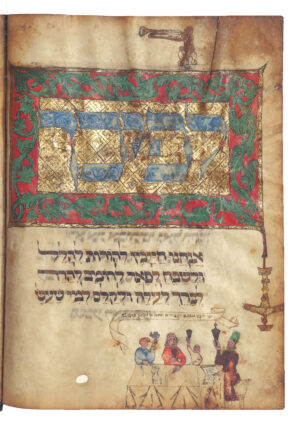

Jewish family celebrating the Passover seder, Hileq and Bileq Haggadah, fol. 20v, Abraham ben Moshe Landau, 15th century, southern Germany (Bibliotheque nationale de France)

Setting the table: Passover and the haggadah

Jewish family celebrating the Passover seder (detail), Hileq and Bileq Haggadah, fol. 20v, Abraham ben Moshe Landau, 15th century, southern Germany (Bibliotheque nationale de France)

At the bottom of this page in a fifteenth-century manuscript, we see a family—a father, mother, and two children—seated together at a table. Even without knowing anything about what is depicted, we can draw some basic conclusions. It was obviously important that they be shown as a family, and they are all holding up cups; the jug on the table further emphasizes that drinking is important in this scene. Also on the table, in front of the father, is an open book, and he may be pointing to a particular text (the words themselves are not actually written in legible letters, and the picture as a whole has suffered damage from moisture). Finally, to the right, we see a large golden lamp, which suggests that the action is taking place at night—why else would they need light? Who are these people, and what is the point of depicting them on this page, which contains Hebrew text and an opening word that is richly ornamented and set against a patterned gold background? The short answer is that they represent a Jewish family celebrating the Passover seder, although there is more going on here than first meets the eye.

The seder was the home ritual celebrated each year on the fifteenth day of the Hebrew month of Nissan (usually in April) to commemorate the Jewish people’s exodus from Egypt and miraculous delivery from slavery, which is recounted in the biblical book of Exodus in the Hebrew Bible. On the first night of the Passover festival, Jews were commanded to tell the story of God’s redemption of the children of Israel and to eat various ritual foods, including matzah (unleavened bread), four cups of wine, and maror (a bitter herb).

In the ancient world and the early Middle Ages, the Passover seder was conducted entirely through spoken word and performance. Beginning around 1300, Jews in Europe began to create or acquire decorated versions of the haggadah, a small book containing the texts used at the seder. The impetus for the creation of the written haggadah was part of a larger European trend in which literacy was increasing, and more people were using books for both religious and secular purposes. For European Jews, it was useful to collect the seder texts in a book, and those books could be decorated to enhance the entire seder experience. One example is this book, known as the Hileq and Bileq Haggadah, which was made in the second half of the fifteenth century somewhere in southern Germany. Unfortunately, there is not enough evidence to be more precise about the date and location of this particular work, but in many ways it is typical of decorated haggadahs in central Europe in the Middle Ages.

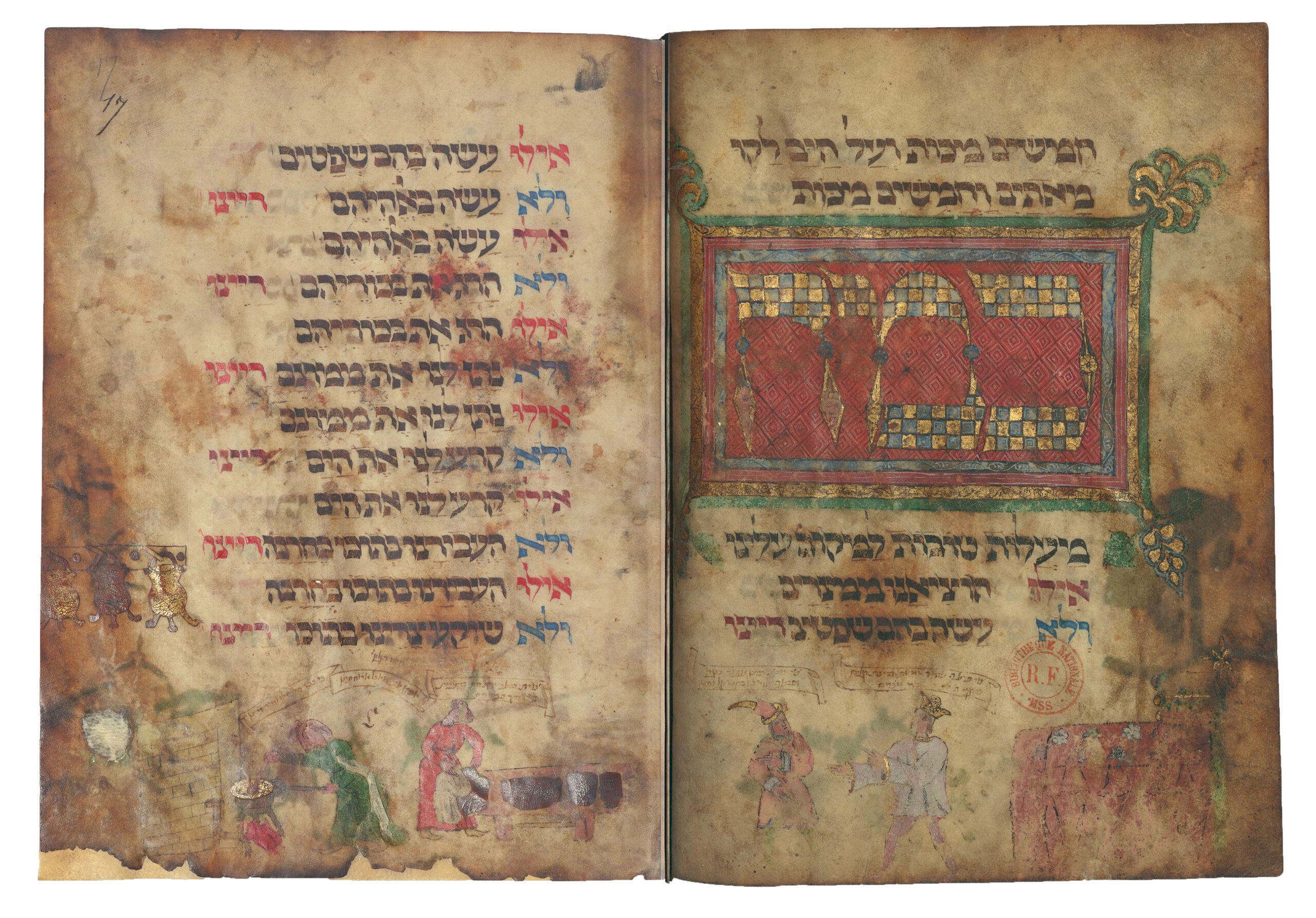

Right: plague of the firstborn; left: women cleaning and preparing the seder meal, Hileq and Bileq Haggadah, fols. 16v-17r, Abraham ben Moshe Landau, 15th century, southern Germany (Bibliotheque nationale de France)

Past and present in the haggadah

Medieval haggadahs, whether made in central Europe (Ashkenaz) or Iberia, regularly included two kinds of illustration: pictures that tell the biblical story of the exodus and depictions of the seder activities themselves. These two facing pages of the Hileq and Bileq Haggadah contain both kinds of illustration.

Hebrew is read from right to left, so the page on the right comes first. The image in the bottom margin shows us, according to the rhyming Hebrew captions, “Image of pharaoh, getting out of his bed in a hurry, because God smote [killed] all the firstborn of Egypt” and “Image of Moses our teacher standing opposite him, and pharaoh about to plead for his life.”

Plague of the firstborn, Hileq and Bileq Haggadah, fol. 16v, Abraham ben Moshe Landau, 15th century, southern Germany (Bibliotheque nationale de France)

The page thus brings to a conclusion a series of images that represent the dramatic ten plagues that God sent to punish the Egyptians for enslaving the Jews and to motivate them to release the Children of Israel from their bondage. Admittedly, the haggadah pictures themselves—a big bed, the crowned king of Egypt in his nightshirt, and Moses confronting him—are not particularly dramatic; compositional sophistication was not a value for this artist (although other examples, like the luxurious fifteenth-century Darmstadt Haggadah, demonstrate that some haggadah artists were quite sophisticated).

Women cleaning and preparing the seder meal, Hileq and Bileq Haggadah, fol. 17r, Abraham ben Moshe Landau, 15th century, southern Germany (Bibliotheque nationale de France)

On the facing page is something altogether different: two women engaged in domestic activities. According to the captions, one is an “Image of the girl wiping the dishes because this is what girls do”; the other caption reads, “Says the picture: I will prepare the food for our meal, because they have already started to say ‘dayenu.’”

Pictures of setting the table and cooking dinner are not illustrations of the dayenu text found on the page itself, which is a list of the great things God did for the Jewish people over the course of the exodus. Nor do they represent a commanded ritual, like eating the matzah, which is depicted elsewhere in the haggadah. They are, instead, candid reflections of the practical aspects of the seder, snapshots of contemporary fifteenth-century life. Expressing this in the mother’s voice makes the lived experience even more vivid: something like “Oh, we’ve reached the point of the dayenu prayer, which means it’s getting close to the meal, so I’d better get dinner ready.” (This is a moment that many contemporary participants in a seder will find familiar!) The picture shows how household labor was divided along gender lines, but what would have stood out to the fifteenth-century readers and viewers is the seamless transition from biblical history on one page to contemporary life on the next. This demonstrated that participating in the seder was an unbroken tradition that reached back to the Bible itself.

!["In every generation, a person is required to see [consider] himself as if he went out of Egypt," Hileq and Bileq Haggadah, fol. 20r, Abraham ben Moshe Landau, 15th century, southern Germany (Bibliotheque national de France)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/20r-detail-870x605.jpg)

“In every generation, a person is required to see [consider] himself as if he went out of Egypt,” Hileq and Bileq Haggadah, fol. 20r, Abraham ben Moshe Landau, 15th century, southern Germany (Bibliotheque nationale de France)

Making and using the haggadah: Abraham, Hileq, and Bileq

Jewish family celebrating Passover seder, Hileq and Bileq Haggadah, fol. 20v, Abraham ben Moshe Landau, 15th century, southern Germany (Bibliotheque nationale de France)

Who was responsible for the 67 marginal text illustrations with their rhymed, often witty, captions? An inscription at the end of the haggadah claims: “The scribe Abraham, the son of Moses Lando, wrote the humble poems, half asleep.” Abraham takes credit for the captions in a way that is superficially modest even as it reveals him to be a rather playful person. Although Abraham does not claim to be the artist, the close coordination between texts and images, and the artist’s apparent lack of professional training, make this likely. The pictures certainly display the kind of playful wit also seen in the captions, as we can see when we return to the picture of the family sitting at the seder.

At this point in the book, the main part of telling the story of the exodus has been completed. The page marks an important moment in the haggadah, because it is one of just six pages that have an enlarged decorated word highlighted with gold, a standard practice in medieval Hebrew manuscripts .

“THEREFORE, we are obligated to thank, praise, laud, glorify, exalt, lavish, bless, raise high, and acclaim He who made all these miracles for our ancestors and for us: He brought us out from slavery to freedom, from sorrow to joy, from mourning to [celebration of] a festival, from darkness to great light, and from servitude to redemption. And let us say a new song before Him, Hallelujah!”

This relatively long and repetitive text hammers home the need to sing thanks to God, which the picture and its caption communicate succinctly: “Image of those who make pleasant music, lifting their [wine] cups when they get to ‘Therefore.’” We have to imagine the original users of the book coming to this point in the haggadah, seeing the beautifully decorated opening word that cues them to begin their expressions of praise, and at the same time seeing an idealized picture of themselves—the family united in performing the required seder activity, led by the father who has, as was the norm, the only haggadah in the household.

Monkey in upper margin of the page, Hileq and Bileq Haggadah, fol. 20v, Abraham ben Moshe Landau, 15th century, southern Germany (Bibliotheque nationale de France)

But what is that at the top of the page? It seems to be a monkey playing a trumpet or trombone-like brass instrument. In thousands of late medieval manuscripts, the margins were a place to expand upon the otherwise serious matters on the page, and animals playing instruments were part of the standard repertoire of medieval marginalia. In this instance, the monkey blowing his horn at the top of the page “announces” the text but also becomes, humorously, a member of the group “who make pleasant music … when they get to ‘Therefore.’” The monkey may also be a visual reward for any member of the family paying close enough attention to spot this unexpected and delightful detail.

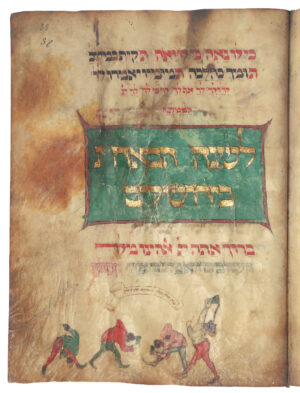

“Next year in Jerusalem,” Hileq and Bileq Haggadah, fol. 38r, Abraham ben Moshe Landau, 15th century, southern Germany (Bibliotheque nationale de France)

We do not know the names of the original owners. One clue might be in the book’s final illustration, near the very end of the haggadah under the customary closing proclamation: “Next Year in Jerusalem.”

Four men are seen in acrobatic poses, each holding a cup—an echo of the four cup-holding family members at the seder. According to the caption, this is “The image of Hileq and Bileq each drinking his share.” Were Hileq and Bileq real people—perhaps the original owners of the book? Are they being praised for drinking the required four cups of wine at the seder? Or are they, as their poses suggest, fanciful characters poking a little fun at what happens by the end of the night when so much wine is consumed? Whatever the answer, which perhaps further research will reveal, the drinking acrobats are a final decoration that must have delighted the fifteenth-century users of this Passover haggadah, much as it continues to do today.

Additional resources

Franziska Amirov, Jüdisch-christliche Buchmalerei im Spätmittelalter: aschkenasische Haggadah-Handschriften aus Süddeutschland und Norditalien (Berlin: Deutscher Verlag für Kunstgeschichte, 2018).

Adam S. Cohen, “The Multisensory Haggadah,” in Les cinq sens au Moyen Age, ed. Eric Palazzo (Paris: Editions du Cerf, 2016), pp. 305–31.

Adam S. Cohen, Signs and Wonders: 100 Haggada Masterpieces (New Milford: Toby Press, 2018).

Jill Caskey, Adam S. Cohen, and Linda Safran, “The golden Haggadah,” Art and Architecture of the Middle Ages: Exploring a Connected World, 2022.

Marc Michael Epstein, The Medieval Haggadah: Art, Narrative, and Religious Imagination (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011).

Joseph Gutmann, “Haggadah Art,” in Passover and Easter: The Symbolic Structuring of the Seasons, ed. Paul F. Bradshaw and Lawrence A. Hoffman (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1999), pp. 132–45.

Mendel Metzger, La Haggada Enluminée: Étude iconographique et stylistique des manuscrits enluminés et décorés de la haggadah du XIIIe au XVIe siècle (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1973).