Michelangelo at times complained that because of the haste the Pope imposed upon him, he was unable to finish it the way he would have liked; for his holiness was always asking importunately when it would be ready. One of these occasions Michelangelo retorted that the ceiling would be finished ‘when it satisfies me as an artist.’Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects (1550) [1]

Raphael, Portrait of Pope Julius II, 1511, oil on poplar, 108.7 x 81 cm (National Gallery, London)

Michelangelo’s pupil and great biographer of renaissance artists, Giorgio Vasari, wrote these words in his book to describe the battle of wills between Michelangelo, the iconic artist of the renaissance, and his belligerent patron, Pope Julius II. At issue was the completion of the Sistine Chapel ceiling. Michelangelo’s retort to the pope’s impatient inquiries, that the ceiling would be done when it satisfied him “as an artist,” would have been unimaginable a century earlier. Vasari has Michelangelo winning the battle, although he noted that Julius II did threaten to have Michelangelo thrown from the scaffolding that allowed him to paint the chapel’s ceiling.

This episode demonstrates the changing status of the artists at the turn of the sixteenth century. It was during this time that the status of the artists evolved from that of artisans to that of heroic geniuses, whose unique talent and singular vision have been credited with paving the way for the modern conceptions of artists as individuals breaking from society’s norms. This shift is partially rooted in a growing appreciation of the individual style of artists by their patrons in the renaissance. It also owes a great deal to the myth-making of authors—such as Vasari—who portrayed the lives and works of Michelangelo, Leonardo, and Raphael as divine callings.

Yet, throughout the renaissance and even into the seventeenth century, artists, like the majority of men and women born outside the privileged circles of merchants, bankers, and nobles, had to work for a living. They accepted commissions based on needs, adhered to the demands of patrons, and often received modest compensation for their artistic output. At this time, artists—painters, sculptors, and architects—shared the same status and outlook as craftsmen, such as carpenters, wool-workers, and blacksmiths. Most artists never reached the heights of fame or wealth that Michelangelo and Raphael achieved—though many made a solidly middle-class living from their work and died in relative obscurity.

Note how Cosimo I de’Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany, is shown at the center of this panel, dominating the space while surrounded by his artists and engineers. Giorgio Vasari, Cosimo I De’Medici and his Architects, Engineers, and Sculptors, finished in 1559, fresco ceiling painting (Sala dei Cinquecento, Palazzo Vecchio, Florence)

The daily life: the workshop and the guild

As with all craftsmen, artists kept shops (botteghe) that often served as their home. These shops, small and often cramped, were located on the bottom floor of larger buildings or could stand alone. They opened onto streets by means of heavy shutters and had counters (banchi) on which transactions with clients were made. Examples of these shops have survived on the Ponte Vecchio in Florence and Ponte Rialto in Venice, which now house expensive jewelry stores.

Andrea Pisano, Architecture, 1348–50, from the Florence Campanile, east side (Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Florence)

Far from our romantic conceptions of artistic studios as serene, isolated workspaces, workshops were loud boisterous places full of activity with the coming and going of apprentices, clients and their servants, and neighbors (who often stopped by for gossip and a bit of wine). To maintain a shop, an artist had to be a member of a guild (an association of craftsmen who worked in the same trade and have risen to the rank of master). Masters generally attracted several apprentices over the course of their working life. During their apprenticeship, young men (and occasionally young women), trained in their art and learned the style of their master. They usually began by acquiring basic skills such as drafting and mixing paints, and then gradually gained proficiency in painting, casting, sculpture, and building, depending on their trade. Workshops were often family affairs, with apprentices following the profession of their father, uncle, or father-in-law. Gentile Bellini, for example, followed his father, Jacopo, into the family business; as did Artemisia Gentileschi, who was trained by her father, Orazio.

![A busy artist's studio. Philip Galle after Jan van der Straet, Nova Reperta: Invention of Oil Painting (Color Olivi) [The distinguished master Eyckius found the olive color advantageous to painters], 1580–1605 (© Trustees of the British Museum)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/download-870x643.png)

A busy artist’s studio. Philip Galle after Jan van der Straet, Nova Reperta: Invention of Oil Painting (Color Olivi) [The distinguished master Eyckius found the olive color advantageous to painters], 1580–1605 (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Unless they enjoyed the special privilege of working for a ruler, renaissance artists’ work was regulated by guilds in ways that their modern counterparts would find confining. The guilds instituted rules that maintained the quality of artistic output and established the price of all commissioned works. Artists could not sell their works without guild membership. During his visit to Venice, the German artist, Albrecht Dürer, was fined several times for working in the city without joining the Venetian guild of painters. On the other hand, guilds gave artists a group identity through devotional and ceremonial practices and gave charity to down-on-their-luck members. Both Botticelli and Lorenzo Lotto had recourse to loans from their respective guilds.

Painted for German merchants for an altar for the Church of S. Bartolomeo near the Fondaco dei Tedeschi, the social and commercial center of the German colony in Venice and intended to declare the artist’s abilities to the Venetian public. Albrecht Dürer, Feast of the Rose Garlands, 1506 (National Gallery, Prague)

Working for a living: what artists made and what they made

Art in the renaissance was never executed without a commission from a patron who was generally a member of the princely or merchant elite or a corporate body, such as municipal government, church, or guild. These patrons dictated the theme, content, and, often, even the form of works. For example, humanists at the court of Pope Sixtus IV advised Botticelli in his painting of The Punishment of the Sons of Korah, an episode from the Old Testament. The fresco was official papal propaganda connecting the figure of the pope with the ancient prophets. Artists, like Botticelli, gladly took up these commissions not from a desire to express themselves, but in order to make a living.

Sandro Botticelli, The Punishment of Korah and the Stoning of Moses and Aaron, 1481–82, fresco (Sistine Chapel, Vatican)

Although some artists, such as Michelangelo and Leonardo, could command enormous sums for their work, most artists struggled to make ends meet and accepted modest commissions from men and women of humble backgrounds. In his account book, the painter, Lorenzo Lotto, recorded his numerous transactions with small-time merchants and fellow artisans. In October 1558, he recorded that he had painted three portraits for the Venetian dyer, Francesco di Canali, and received twelve scudi for each of them. Lotto had to travel up and down the eastern coast of the Italian peninsula, from Venice to Loreto, in search of work. It is no wonder that he had to borrow money from his guild to get by.

This sitter has been identified as Bartolomeo Carpan; a friend of Lotto’s tried by the Inquisition for heresy. The portraits of the dyer has not been found. Lorenzo Lotto, A Goldsmith in Three Views, c. 1525–35, oil on canvas, 52 x 79 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

Andrea del Castagno, David with the Head of Goliath, c. 1450–55, 115.5 x 76.5 cm, tempera on leather on wood (National Gallery of Art)

Scores of lesser-skilled artists created objects for everyday devotion, such as paintings of the last supper or statuettes of the Virgin Mary or the saints. Even artists that are well-known today accepted more mundane commissions.

The Florentine painter, Andrea del Castagno, was not above painting a depiction of David with the head of Goliath on a parade shield (used for display rather than physical protection) in addition to working on frescoes in monasteries and churches.

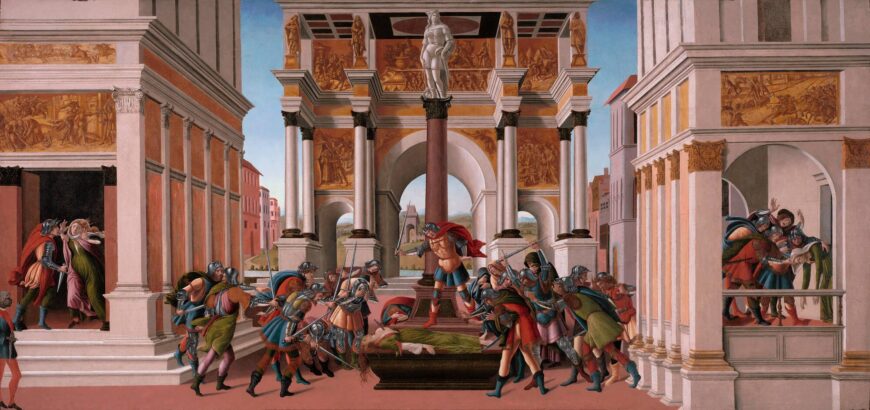

Similarly, Botticelli did not blink an eye when wealthy patrons asked him to paint mythological and narrative scenes on wedding chests (cassoni). Embarking on a career as an artist throughout much of the renaissance was a job, not a vocation, and the majority of artists, just like today, failed to attain the fame and wealth of the great luminaries of the age.

Painted for a wedding chest (cassoni), Sandro Botticelli, The Story of Lucretia, c. 1500, tempera and oil on panel , 83.8 x 176.8 cm (Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston)

Painting, sculpture, and building was viewed as mechanical work and an ignoble art. Artists were seen as craftsmen rather than inspired geniuses on the level of the poet or humanist scholar. Like all craftsmen, artists sold their works for profit, which was seen as an unseemly act for gentlemen and nobles who lived off their family patrimony and inheritances. The elite culture at the time regarded all manual labor as beneath the dignity of nobles, scholars, and patricians. Men and women from these classes were people of the mind, not the hands. Painters, sculptors, and other artists literally got their hands dirty with paint and dust.

Changing times: from artisan to artist

Artists chaffed at these attitudes. Donatello, known for his cavalier indifference to money, threw a bust into the street, shattering it, when the patron who commissioned it insulted the sculptor by suggesting he had been overcharged. Leonardo was particularly sensitive to those who had a low opinion of the artists’ trade. Although the status of the artist had improved by the early sixteenth century, Leonardo could still complain in his famous notebooks that

You have set painting among the mechanical arts. Truly were painters as you are to praise their own works in writing, I doubt it would endure the stigma of so base a name. If you call it mechanical because it is by manual work that the hands design what is in the imagination, your writers set down with the pen by manual work what originates in your mind. [2]

Leonardo raised painting to the level of poetry and other forms of writing because both drew on the fertile imagination of the mind. He concluded by arguing that painting was superior to writing since the painter could convey ideas in their totality while poets did so line by line.

Perugino, The Battle of Love and Chastity, c. 1500–25, tempera on canvas, 160 x 191 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

As Leonardo’s complaint reveals, artists increasingly saw themselves as important contributors in commissioned works. True, the patron still decided upon the theme and iconography, but artists began to assert themselves in completed works of art. Thanks to the rise of humanism and its educational system, many artists were well-versed in iconographic themes found in the Bible and in the mythologies and histories of classical antiquity. They began to voice strong opinions on how biblical and classical scenes were to be depicted.

For example, the painter Perugino earned the ire of the marquess Isabella d’Este when he painted the allegory of Love naked in the painting, The Battle between Love and Chastity, against her wishes. The marquess believed that Perugino portrayed Love nude to show off his skill, but surely he was also adhering to a long-standing iconographic tradition. Likewise, Veronese ran afoul of the Roman Inquisition in 1573 when he added buffoons, dwarfs, and German soldiers to a Last Supper commissioned by the friars of the Dominican monastery of Santi Giovanni e Paolo in Venice. When asked by inquisitors why he included such scandalous figures in in his painting, he claimed, “We painters take the same license as do poets and madmen.” [3]

Paolo Veronese, Feast in the House of Levi, 1573, oil on canvas, 560 x 1309 cm (Accademia, Venice)

Despite long-standing prejudice against painting and sculpture as mechanical arts, many patrons in the sixteenth century reconsidered the status of artists. This was in large part due to a greater appreciation of the skill and unique style of individual artists. Many patrons began to collect works of great artists, who were now acquiring a degree of fame for their art. Isabella d’Este, for example, sought to collect paintings from all the leading masters of her day, including Mantegna, Perugino, and Leonardo, which she kept in a room specifically designed to show off these works.

Titian proudly wears his symbol as a Knight of the Golden Spur (a gold chain) and holds a paint brush, symbol of his occupation, a nice juxtaposition of his profession and claims of gentility. Titian, Self-Portrait, c. 1562, oil on canvas, 86 x 65 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid)

As appreciation for their skill increased, so did the social status of many artists. Now, they were sought after by princes and popes at their courts and their works highly coveted in the personal collections of Italian and, later, European nobility. Leonardo worked in comfort as the court painter of Ludovico Sforza, the Duke of Milan. Later, he, Cellini and other Italian artists traveled to France to work at the court of King Francis I. Some artists were accorded special honors and even knighted. Charles V, King of Spain and Holy Roman Emperor, made the Venetian painter Titian a Knight of the Golden Spur for his work for the imperial court.

By the sixteenth century, the status of the artist had changed. Artists could make a claim for a higher status and many of them, such as Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Titian could make good on such claims. By the mid-sixteenth century, these changing attitudes were enshrined in Vasari’s Lives of the Artists, which praised artists from Giotto to Michelangelo as men inspired by an inner genius and divinely gifted with rare talent. In each of these lives the artists take on a heroic light that prefigured and shaped the modern views of art and the artist.

Notes:

[1] Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Artists, vol. 1, trans. George Bull (London: Penguin, 1965), p. 356.

[2] Leonardo da Vinci, Notebooks (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1952), p. 189.

[3] David Chambers and Brian Pullan, eds., Venice: A Documentary History, 1450–1630 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001), p. 234.

Additional resources

Leonardo’s letter to the Duke of Milan (Smarthistory essay).

Bruce Cole, The Renaissance Artist at Work: From Pisano to Titian (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1983).

Peter Burke, The Italian Renaissance: Culture and Society in Italy, 3rd edition (Princeton: Princeton University Press 2014).

Paul Oskar Kristeller, Renaissance Thought and the Arts (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980).

Andrew Landis and Carolyn Wood, eds., The Craft of Art: Originality and Industry in the Italian and Baroque Workshop (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2016).