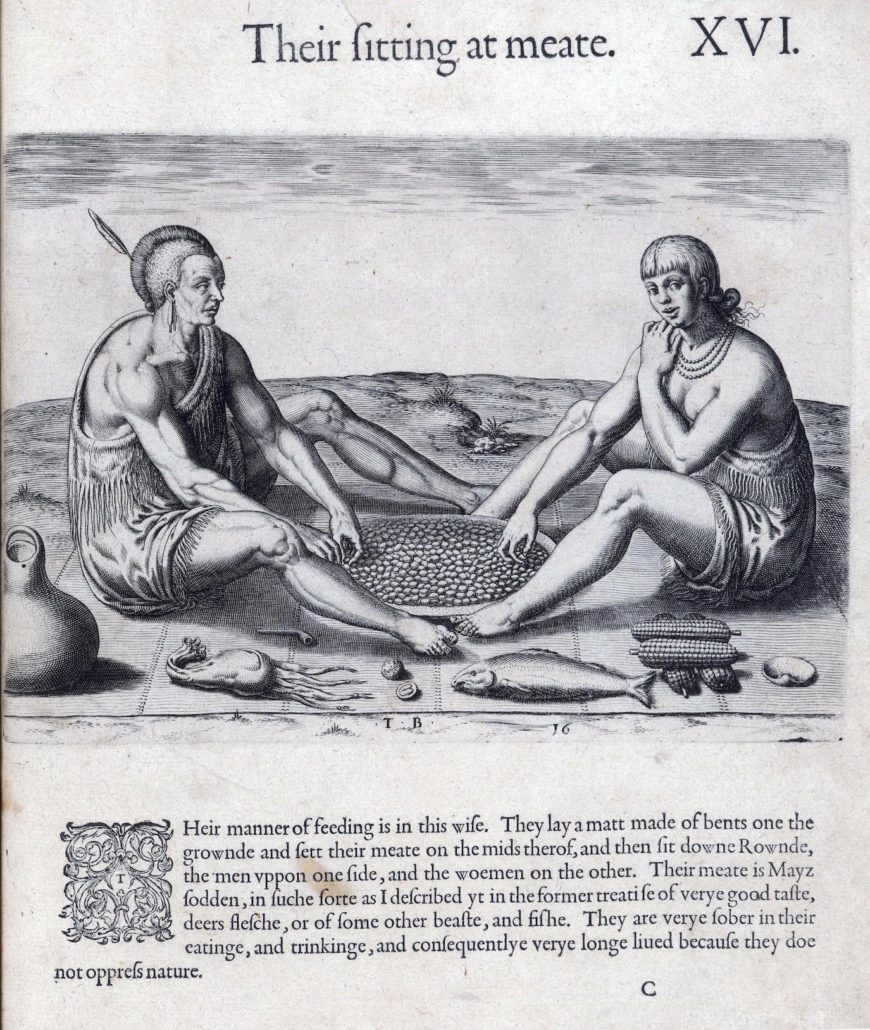

John White, “Their sitting at meate,” 1577–90, watercolor, 20.9 x 21.4 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

“Sitting at meate” means to sit at a meal and in the watercolor above by John White, an Algonquian man and woman do just that. The man and woman sit opposite each other on a reed mat, sharing a platter of what may be hulled corn (corn boiled to remove the hulls). The male has a mohawk-style haircut and wears a single feather, with a fringed tunic covering his torso. The female wears a beaded necklace and a three-quarter length fringed dress. Her breasts are exposed, but modestly covered by the hand she reaches towards her mouth. While the man looks at the woman, the woman seems to look past her companion.

John White, the artist who painted the watercolor, was also a failed governor of the English Roanoke colony in what is now North Carolina but was then referred to by the English as Virginia. He painted many scenes of the Algonquians who he had contact with while living there in 1585. While his watercolors are ethnographic in nature—that is, they are meant to document their customs, clothing, foods, and natural resources, they also served a propagandistic purpose: White made them not only to be informational to Europeans, but also to encourage colonization of North America.

Theodor de Bry, “Their sitting at meate,” engraving, 15.2 x 21.2 cm, in Thomas Hariot, A briefe and true report of the new found land of Virginia, of the commodities and of the nature and manners of the naturall inhabitants, 1590 (The John Carter Brown Library), after a watercolor of John White, 1577–90

White’s watercolors were made into prints and included in books. In the print version of “Their sitting at meate,” the Algonquians’ bodies become more muscular. Their legs extend farther toward each other, and like the more toned bodies, their faces are generalized and less round, conforming to European standards of beauty for both sexes in the sixteenth century. Significantly, more food and natural resources are added to the scene: a stack of corn, a fish, a walnut, and an oyster or mussel shell, in addition to a gourd for water, a pipe, and tobacco pouch. A landscape recedes behind the two figures.

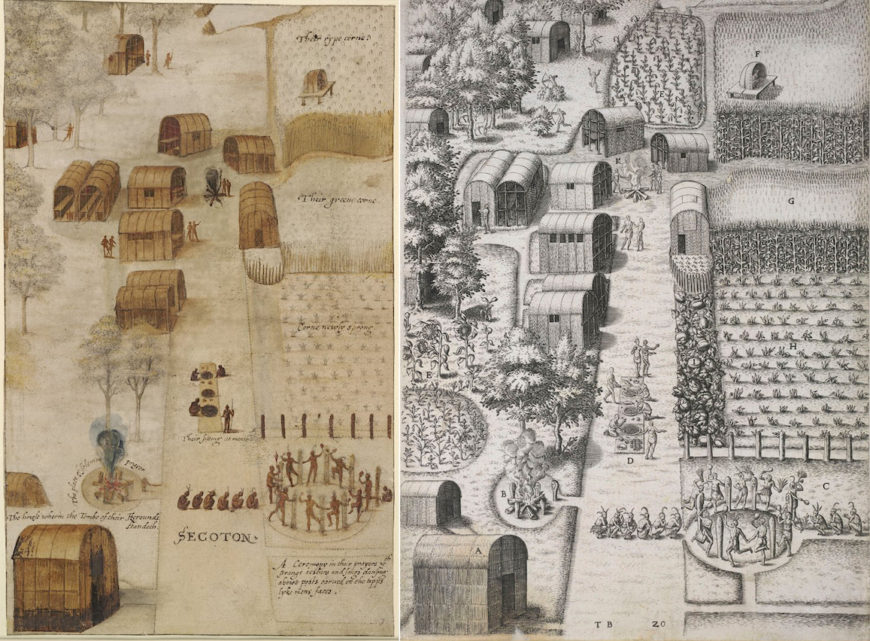

The town of Secoton (bird’s-eye view of town with houses, lake at the top, fire, fields and ceremony). Left: John White, 1585–93, watercolor over graphite, heightened with white (British Museum); Theodore de Bry, 1590, engraving (after the watercolor by John White) for volume 1 of Collected travels in the east Indies and west Indies which reprinted Thomas Hariot, A briefe and true report of the new found land of Virginia, of the commodities and of the nature and manners of the naturall inhabitants (British Library)

From watercolor to print

The De Bry brothers (Johann Theodor and Johann Israel) engraved many scenes of Algonquians after White’s watercolors and reprinted them in their series of the Grands Voyages. The De Brys most likely received John White’s watercolors from the English geographer Richard Hakluyt (who also sought to claim Virginia and encourage its colonization). The Grands Voyages included travel accounts by various European authors, and were published in English, Latin, German, and French. The De Bry engravings after White’s watercolors also accompanied Thomas Hariot’s Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia, first published in London in 1588.

Theodor de Bry, “Their sitting at meate,” engraving, 15.2 x 21.2 cm, from Thomas Hariot, A briefe and true report of the new found land of Virginia, of the commodities and of the nature and manners of the naturall inhabitants, 1590 (The John Carter Brown Library), after a watercolor of John White, 1577–90

Like most illustrated books published at the time, the De Brys’ Grands Voyages was a collaborative affair. Printer, publisher, author, artist, and engraver all had to come together for the common purpose of selling a product. While Hakluyt and White had English interests in mind, the famous printmakers could publish the images along with descriptions in their multivolume travel series and profit from their distribution and sale. Prints reached far greater audiences because of the numbers reproduced and their portability.

Visual propaganda

Theodor de Bry, detail of Algonquian woman, “Their sitting at meate,” engraving, 15.2 x 21.2 cm (The John Carter Brown Library), after a watercolor of John White, 1577–90, from A brief and true report of the new found land of Virginia, 1590

In Theodor de Bry’s “Sitting at meate,” he used the common European visual language of classicizing muscular and idealized bodies, probably to help European viewers understand the new ethnographic, zoological, and botanical information. This was common practice in travel accounts of the time. Moreover, the addition of food and commodities available in the new lands (such as pearls and tobacco) promoted the idea of Virginia (present-day North Carolina) as bountiful.

His print amplified the propagandistic aim of presenting the English colony as chock full of good things to eat and commodities to sell. In the print, the woman looks at the viewer, as if an invitation to feast, if not literally, then by looking. Certainly, the addition of these food stuffs and natural resources provided zoological and botanical information to European readers. The visual and textual descriptions of clothing continue to provide contemporary historians with information about sixteenth-century Algonquian dress.

As shown in both the print and the watercolor, men and women wore similar clothes. Usually made of deerskin, the covering might be a single apron-like garment, doubled over at the top and tied at or above the waist. Alternatively, some men and women wore the deerskin draped from one shoulder, as seen here. Both were typically fringed. The fringe or belt could indicate rank; pearls or animal tails signified a person’s status. Bodies and clothing also could be decorated with pearls, copper, and natural dyes. Pearls were a particularly enticing commodity from the Chesapeake area that the English wanted to exploit. Derived from river mussels or oysters, pearls were traded across the Americas and Europe and used in a variety of items, from special tableware to jewelry for the wealthy. Pearls featured frequently in various English accounts of the southeast coast of North America. English readers could consider how harvesting pearls there could bring wealth to investors, and undermine Spain’s hold on pearl fisheries on the east coast of South America.

Theodor de Bry’s addition of these elements to “Their sitting at meate” served multiple purposes: he was able to incorporate information provided by White in other watercolors, such as botanical and zoological information, but not create individual new plates for each plant or animal, which would have been an additional expense. He could combine the natural and ethnographic information in one plate, saving material and labor costs. The De Brys published only 23 engravings from 63 watercolors; many of the other 40 watercolors were botanical or zoological novelties. Adding in these natural resources to a scene with the Algonquians underscored the message of bounty and fertility of Virginia to investors and potential settlers, and may have also appealed to scientists interested in the flora and fauna of the land. The De Brys increased their audience, while not increasing the cost of production. The changes Theodor de Bry made in “Their sitting at meate”—and the changes all the Dr Brys made for the series of engravings—increased the images’ versatility and readability to a variety of audiences. They also show how profit was important for all parties involved, from nation and colonizer to publisher or potential investor.

Notes:

[1] Michael van Groesen, Representations of the Overseas World in the de Bry Collection of Voyages (1590–1634) (Leiden: Brill, 2008), p. 112.

Additional resources:

Encyclopedia Virginia, “Drawing on First Impressions: An interview with Joyce Chaplin.” December, 2014

Michael van Groesen, Representations of the Overseas World in the de Bry Collection of Voyages (1590–1634) (Leiden: Brill, 2008)

National Park Service, “Indian Dress and Ornaments in Eastern North Carolina”

Molly Warsh, American Baroque: Pearls and the Nature of Empire, 1492–1700 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018)