Francisco de Arruda, The Tower of Belém, 1514–19. Commissioned by King Dom João II and executed under his successor King Dom Manuel I. Lisbon, Portugal, view from Northeast (photo: Alvesgaspar, CC BY-SA 3.0)

A visit to Lisbon today is not complete without a day trip to the nearby suburban neighborhood of Belém (Bethlehem), which travelers can access by a 25-minute picturesque tram ride from the center of city. Among the main attractions? Possibly a bakery, Pastéis de Belém, known for specializing in the original pastéis de nata, a custard tart created at the nearby Mosteiro dos Jerónimos (Hieronymites Monastery), the next must-see attraction in Belém.

After visiting the monastery and moving towards the Tagus River, visitors gradually begin to see the Torre de Belém (Tower of Belém) rising on the horizon as if emerging from the water. Together with the monastery, the tower remains one of the main symbols of Portugal’s global expansion during the so-called Age of Exploration (beginning in the mid-to-late 15th century), when Europeans increasingly traveled to different parts of the world to expand their knowledge of and control over resources, people, and lands.

The Tower of Belém celebrates the expedition led by navigator Vasco da Gama, who established a maritime trade route from Portugal to India in 1497–98. The Tower is also known as the Tower of Saint Vincent, in honor of Lisbon’s patron saint.

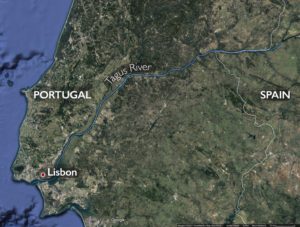

The Tower is located where the Tagus River (the longest river on the Iberian Peninsula) meets the Atlantic Ocean. Mariners arrived in or departed Lisbon from Belém’s beach (Praia do Restelo), which provided shelter from the strong Atlantic winds.

The Tower is located where the Tagus River (the longest river on the Iberian Peninsula) meets the Atlantic Ocean. Mariners arrived in or departed Lisbon from Belém’s beach (Praia do Restelo), which provided shelter from the strong Atlantic winds.

In the fifteenth century, Infante Dom Henrique, known today as Prince Henry the Navigator, built a small chapel at the beach dedicated to Santa Maria do Restelo (also known as Santa Maria de Belém), and it is believed that Vasco da Gama and some of his crew prayed there prior to departing on their voyage to India. As it became more popular, the chapel became a parish and was eventually incorporated by the Hieronymites Monastery (construction here began in 1501–02). Envisioned by Dom Manuel as a pantheon for his dynasty, the monastery housed monks whose roles included praying for the soul of the king as well as for seafarers leaving Lisbon. Funded mostly by income from Portuguese maritime trade with India, the monastery would come to symbolize the association between Portuguese expansion and Dom Manuel’s reign as well as the power of the monarch.

The Torre de Belém: bastion and tower

The Tower’s purpose was to protect the entrance to Lisbon’s port, joining a larger group of pre-existing defensive structures. These include the Fort of São Sebastião da Caparica and the Tower of Santo António at Cascais, which were also commissioned by Dom João II in the late fifteenth century. Positioned directly across from each other, the Tower of Belém and Fort of São Sebastião da Caparica allowed for gunfire from both banks of the Tagus, protecting the city from potential invaders. The Torre of Belém also served as a customs and health checkpoint for those arriving in Lisbon. Writing in the sixteenth century, Portuguese chronicler Damião de Góis claimed that the tower was designed in a way that “no ship could pass by without being seen.” [1]

Despite landfills and silting around the structure, the 98-foot tower has retained its original, two-part design. Made of pedra lioz, a local limestone widely used in Portugal during this period, the complex features a bastion shaped as a hexagon and comprised of a terrace and a lower level as well as the rectangular tower itself, which is five stories high. The combination of the tower (a medieval military structure) with the bastion (a Renaissance type) reflects a transitional phase in Portuguese architecture of the period.

Barrel vault, lower level of the bastion with canons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

The lower level of the bastion features a large fan vault and 17 openings for canons. Dungeons existed below this lower level to store gunpowder, and from 1580 onwards, they also served as a prison.

Smaller watchtower topped with a cross of the Order of Christ and crenellated parapets, Tower of Belem, Lisbon, Portugal (Patrick Clenet, CC BY-SA 3.0)

There are watchtowers at each of the corners of the open terrace of the bastion. A stylized cross rests at the top of each tower and also decorates the crenellated parapets (low walls punctuated with gaps) of the complex. This cross emphasized Dom Manuel’s role as Grand Master of the Order of Christ, a post Henry the Navigator had also held, since 1484 (until his death in 1521). Derived from the Knights Templar, a Catholic armed religious order that participated in the Crusades, this military order helped finance Portuguese voyages, and as a result, their cross was featured on Portuguese sails of the period and became a symbol of Portuguese exploration.

The opening to the courtyard is marked by pinnacles and columns with armillary spheres. The Tower of Belém, built by Francisco de Arruda c. 1514–19, Lisbon, Portugal (photo: Georges Jansoone, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Dom Manuel I of Portugal in his own Liber Missarum, c. 1500 (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek)

At the center of the terrace on the bastion, visitors can look downward to a small interior courtyard. This courtyard may have been designed for ventilation, dissipating smoke created by cannon fire. It was covered in the late sixteenth century with barracks but has been open since renovations took place in the late nineteenth century. The opening has been surrounded by a low wall decorated with pinnacles as well as columns supporting armillary spheres (celestial spheres)—an important nautical instrument during the period and Dom Manuel’s personal emblem. An image in the king’s Liber Missarum shows a celestial sphere behind the kneeling king—just like those at the Tower. A statue of the Virgin with the Christ child is at the center of the terrace as part of the wall around the opening, facing the river as if the two were watching over the navigators and the Tagus.

The five levels of the Tower of Belém, built by Francisco de Arruda c. 1514–19, Lisbon, Portugal. View from Northeast (photo: Alvesgaspar, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The tower’s five levels are connected by a spiral staircase (inside) and feature the Sala do Governador (Governor’s Hall) at the first level. The name of the room likely refers to the existence, in the sixteenth century, of the office of Governor of the Tower as the on-site royal representative with administrative, judicial, and military authority.

In this room, a well connected to a cistern provided water to the building, as visible from the rope marks on the stone, and one can also access two additional watch towers. Starting in 1519, construction of the Casa do Governador da Torre de Belém (House of the Governor of the Tower of Belém) began nearby as a residence for the officer.

View from the balcony, Kings’ Hall, Tower of Belem, Lisbon, Portugal (photo: Concierge.2C, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The second story features the Kings’ Hall (Sala dos Reis), which received its name from the belief that monarchs enjoyed watching the ships on the river from the southern-facing loggia. On the floor of the loggia, eight machicolations (floor openings) provided protection against possible invaders by creating space for someone to throw objects or boiling water, or even fire guns from above. This room also features three additional balconies on each side of the tower. On the exterior and facing the mainland (north), one can see statues of St. Vincent, the patron of the tower and Lisbon, and the Archangel Michael.

The Audience Hall on the third story was used for meetings and features a fireplace.

Portion of the tierceron vault in the Chapel, Tower of Belem (photo: Sheila Thomson, CC BY 2.0)

On the fourth floor, a Chapel is marked by a spectacular tierceron vault (a vault with additional interconnecting ribs) featuring by the armillary spheres, the coat of arms of Dom Manuel, and the cross of the Order of Christ. Another terrace crowns the structure, offering stunning views of the Tagus.

On the outside, these last two levels are highlighted by crenellations, contributing to the tower’s fortress-like appearance and underscoring its defensive associations.

The Manueline style

The Tower of Belém is one of the best examples of the Manueline style of architecture that was common in early sixteenth-century Portugal. This style, which spread not only throughout Portugal but also its empire, incorporated Gothic and Italian Renaissance features. For example, on the exterior colonnade, round arches resting on columns evoke contemporaneous Italian architecture; the balcony is similar to the Ca d’Oro‘s in Venice, and the arcade looks like the church of Santo Spirito in Florence. However, ribbed vaults, slender columns, gargoyles, and tracery at balcony parapets hint at the Gothic style traditional in Portugal in the 1400s. Similar to the structure itself, which combines medieval (a tower) and Renaissance (a bastion) components, the style of the Torre de Belém offers a blend of these two traditions.

Another important characteristic of the style is the presence of maritime motifs. At the Tower, particularly on the river-front southern façade, twisted ropes marking friezes and armillary spheres embody the building’s association with navigation. Surrounding Dom Manuel’s coat of arms, these symbols also represent the monarch as a driving force in Portugal’s oceanic explorations. More symbolic, the crosses linked with the Order of Christ and found throughout the building further emphasize the structure’s connection to seafaring and exploration.

Lleft: Tower of Belem with the location of the rhinoceros indicated (photo: Zero, CC BY-SA 3.0); right: rhinoceros gargoyle (photo: RimerMoshe, CC BY_SA 4.0)

A rhinoceros with global connections

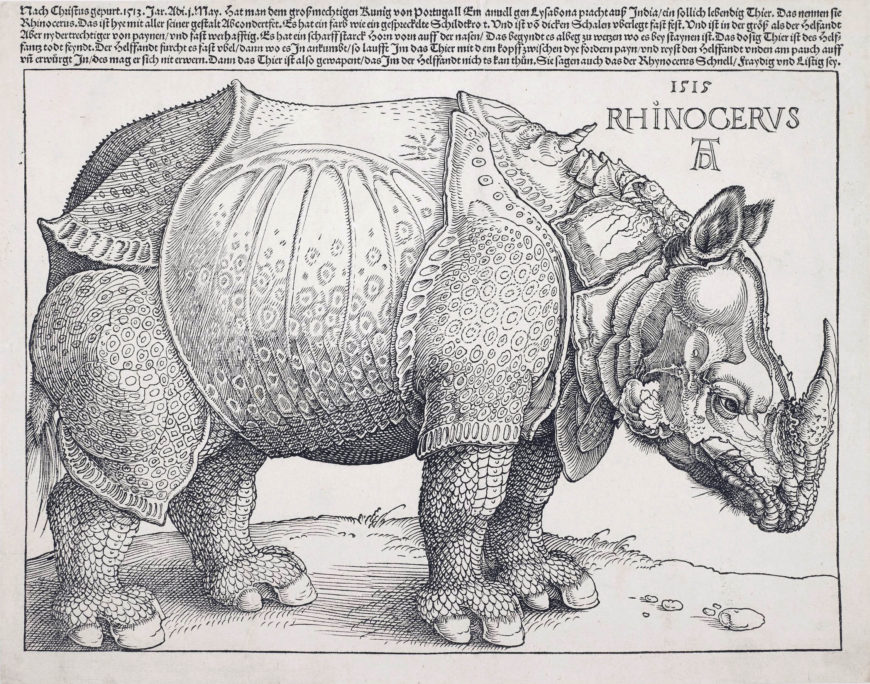

While the motifs associated with the Manueline style signal the expansion of the Portuguese territorial power, the carved front of a rhinoceros found in one of the watchtowers further underscores Portugal’s international connections. A living rhino was gifted by Sultan Muzaffar Shah II during negotiations over the construction of a Portuguese fort in Diu, an island off the northwest coast of India. The animal survived a four-month maritime journey before arriving at the Tower in 1515. This is thought to be first rhinoceros to arrive in Europe since the time of the Roman Empire more than a thousand years earlier, and the animal became symbolic of Portuguese global connections and was ultimately immortalized in a print by the German artist, Albrecht Dürer.

Albrecht Dürer, Rhinoceros, 1515, woodcut and letterpress, 21.2 cm x 29.6 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Notes:

[1] Cited in Manuel Bernardes Branco, Historia das Ordens Monasticas em Portugal, vol. 1 (Lisbon: Livraria Editora de Tavares Cardoso & Irmão, 1888), p. 261

Additional resources:

See more photo of the Tower on the Google Arts and Culture project

Annemarie Jordan Gschwend and Kate Lowe, “Princess of the Seas, Queen of Empire: Configuring the City and Port of Renaissance Lisbon,” in The Global City: On the Streets of Renaissance Lisbon (Paul Holberton, 2015)