Tshibumba Kanda Matulu, Le 30 juin 1960, Zaïre indépendant, c. 1970–73, acrylic on flour sack, 45.72 x 63.5 cm (Virginia Museum of Fine Arts) © Estate of Tshibumba Kanda Matulu

How does one learn about history? In my case, I have learned about the histories of the United States and other countries through history classes and lectures, history books, novels, period dramas, museums, monuments, and visiting historical landmarks. People also learn about history from family stories passed down from generation to generation, from oral histories, online discussion threads, documentaries, television shows, and videos posted on platforms like YouTube.

Envisioning history

Map with the cities Kinshasa and Lubumbashi in Democratic Republic of the Congo (underlying map © Google)

Congolese painter Tshibumba Kanda Matulu envisioned creating the history of Zaïre (present-day Democratic Republic of the Congo) in a series of one hundred paintings in an effort to educate his people about the history of their country. While his series starts with life before European contact in the 15th century, it focuses largely on Belgian colonization and the decade following independence from Belgium in 1960. He realized his vision after befriending the expatriate anthropologist, Johannes Fabian, who provided financial support and encouragement to the artist to paint this series. In 1973–74, Tshibumba brought to Fabian paintings that portrayed his version of the country’s history. [1] After Tshibumba laid down the paintings in Fabian’s living room, he narrated each scene, and then conversed with Fabian.

The paintings from Tshibumba’s History of Zaïre were published in 1996 by Fabian in the book, Remembering the Present: Painting and Popular History in Zaire. Each painting is accompanied by Tshibumba’s narration, fragments of conversations between Tshibumba and Fabian, and clarifying information from Fabian. Sadly, Tshibumba likely did not live to see the publication of the book. In the preface, Fabian notes that the two kept in contact after he left Zaïre in 1974. However, after 1981, Tshibumba’s whereabouts were unknown and he has not been heard from since. Fabian and one of his colleagues attempted to locate him in the 1980s, but with no success.

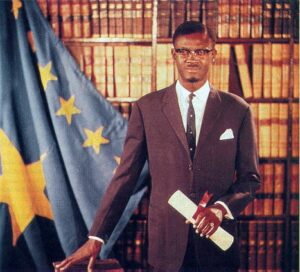

Official Congo government portrait of the Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Patrice Lumumba, 1960

A prime minister and a king

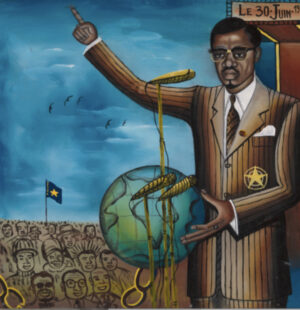

One of the most reproduced paintings from Tshibumba’s History of Zaïre is Le 30 juin 1960, Zaïre indépendant (June 30, 1960, Independent Zaïre). [2] The painting portrays a significant historical event: in the capital city of Kinshasa (formerly called Léopoldville), the first democratically elected prime minister, Patrice Émery Lumumba, delivered a speech in front of a crowd and in front of the Belgian king, Baudouin (who is to the right), during the celebration of Zaïre’s independence from Belgium. In his speech, Lumumba openly condemned and criticized the Belgians for the atrocities they committed under their colonial authority. The title of the painting appears in the upper right corner as a banner. The choice to include the name “Zaïre” for the title is anachronistic, as the country was still known as the Belgian Congo. In 1971, Mobutu Sese Seko changed the names of the country and its largest river to Zaïre in an effort to replace names given by the colonizers with indigenous names. [3]

Detail, Tshibumba Kanda Matulu, Le 30 juin 1960, Zaïre indépendant, c. 1970–73, acrylic on flour sack, 45.72 x 63.5 cm (Virginia Museum of Fine Arts) © Estate of Tshibumba Kanda Matulu

In the center we see Lumumba, addressing the smiling crowd of men and women. Deep in the background, a blue flag with a large, central yellow star and six smaller stars on the left represents the flag of Zaïre from independence day in 1960 to 1963. Outfitted in a striped suit, white button-down shirt, patterned tie, and handkerchief in his chest pocket, Lumumba raises his right arm and points towards the sky with his index finger. His left hand touches a globe that depicts a stylized image of the African continent. At the bottom of the globe, and to the left, a chain is represented. Since the subject of the painting is about independence from Belgium, it is likely that the broken chain (cropped by the edge of the painting) signifies the break with Belgium.

Tshibumba Kanda Matulu, Le 30 juin 1960, Zaïre indépendant (detail), c. 1970–73, acrylic on flour sack, 45.72 x 63.5 cm (Virginia Museum of Fine Arts) © Estate of Tshibumba Kanda Matulu

To the right and behind Lumumba is King Baudouin of Belgium, outfitted in a khaki suit, red sash, white button-down shirt, black tie, and other accessories. Holding a hat and sword in his hands, the king smiles widely and tilts his head slightly forward. Tshibumba points out that in reality, Baudouin was angry as he listened to Lumumba. He notes, “A king has to smile when it is difficult. He must put on a little smile.” [4] Behind him is a cloth backdrop reminiscent of the national flag at the time Tshibumba painted this work in the early 1970s: a background of blue and two vertical bands of red outlined in yellow. In the bottom right corner of the painting, we see the painter’s signature, Tshibumba K.M.

Tshibumba’s history: fact or fiction?

Tshibumba noted that the point of his history series “is to help one another so that we learn the history of our country correctly.” [5] While the majority of his paintings in his history series are based on historical events, Fabian points out that Tshibumba is “an interpreter of his country,” and what he “shows and tells is impressive; it is often amusing, shocking, incredible, and plainly erroneous. Above all, his History is not just a story but an argument and a plea.” [6] Fabian notes that there are discrepancies between the histories portrayed in Tshibumba’s paintings and histories produced by Congolese and outsider journalists and scholars, but Tshibumba’s voice is valuable and should not be dismissed. Indeed, his perspective is evident in many of his paintings.

Tshibumba Kanda Matulu, La Mort historique de Lumumba, Mpolo et Okito, c. 1970–73, acrylic on flour sack, 44.93 x 71.12 cm (Virginia Museum of Fine Arts) © Estate of Tshibumba Kanda Matulu

For example, in La Mort historique de Lumumba, Mpolo et Okito (The historical Death of Lumumba, Mpolo and Okito), Tshibumba depicts the assassinations of Lumumba and his associates, Maurice Mpolo, and Joseph Okito. They were murdered on January 17, 1961, but their deaths were only announced publicly three weeks later (on February 13). At the time, the details of their assassinations were disputed. For La Mort historique, Tshibumba takes creative license and imagines their deaths in his painting. We see Lumumba wearing a white tank top, striped dress pants, a gold watch, and belt, lying on the ground. His eyes are closed, his arms are outstretched in front of him (with untied rope, perhaps showing that he was bound). Behind him are Mpolo and Okito, who are obscured by Lumumba’s body.

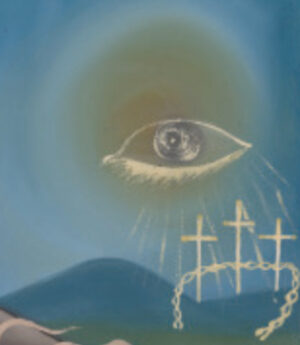

Tshibumba Kanda Matulu, La Mort historique de Lumumba, Mpolo et Okito (detail), c. 1970–73, acrylic on flour sack, 44.93 x 71.12 cm

Tshibumba clearly saw Lumumba as a martyr and national hero. In the painting, he draws a connection between the deaths of Lumumba and Jesus Christ. In the background to the right, we see Golgotha, where Jesus and two thieves were crucified. Golgotha is represented by three crucifixes encircled by a crown of thorns (which was placed on Jesus’ head), and an eye floating above them. Tshibumba depicts Lumumba with a bleeding wound on the right side of his torso, paralleling the wound on Jesus’ side, where he was pierced during his crucifixion. The presence of Mpolo and Okito echoes the presence of the two thieves that are crucified alongside Jesus. Tshibumba said, “…in my view, Lumumba was the Lord Jesus of Zaïre. Above, I painted six [small] stars, because he died for unity [of Zaïre].” [7] In the upper left of the background, we see the national flag from 1960–63: a large yellow star with six small stars arranged vertically to the left.

Tshibumba’s view that Lumumba was a national hero was not uncommon at the time he painted his series. Although Mobutu led a coup d’état against Lumumba in September 1960, ordered Lumumba’s arrest in December 1960, and was involved in his assassination, Mobutu declared in a speech that Lumumba was a national hero. This was a strategic move meant to unify the country’s people and to legitimize Mobutu as the rightful successor of Lumumba. [8]

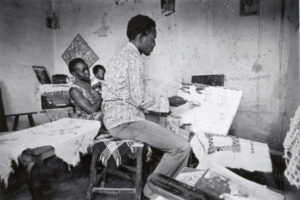

Etienne Bol, Tshibumba Kanda Matulu painting, 1973, printed 2015, digital print on diasec mount, 45.72 x 60.64 cm (Virginia Museum of Fine Arts) © Etienne Bol

Congolese popular painting

Tshibumba’s work is often regarded as exemplary of Congolese popular painting, which emerged during the 1960s and 1970s in urban cities (such as Lubumbashi, where Tshibumba was born) following Belgian colonial rule. Congolese popular painting is “generally understood to refer to nonacademic paintings produced for both local and international audiences … comprising mostly figurative paintings that provide some form of social and/or political commentary on past and present.” [9] The phrase “nonacademic paintings” points to the training of their creators—mainly, painters who have not had formal training in school and produce and sell their paintings on the street, as opposed to galleries or museums. These painters tend to create paintings with the same themes repeatedly (with modifications) and make their living selling these works to local clients, expatriate patrons, or tourists. The themes and subject matter (such as landscapes and flora and fauna) that painters portray vary and depend on the expectations or tastes of their clients. Generally, buyers would have a preference for certain subjects and would buy one or two works from one particular painter. These paintings would be hung in domestic spaces and act as conversation pieces.

While Tshibumba’s History of Zaïre stems from Congolese popular painting, it is exceptional because he was at liberty to paint what he believed to be the significant events in his country’s history thus far. Moreover, due to the publication of Remembering the Present, Tshibumba’s paintings were not just viewed locally; they were made available to international audiences.

Notes:

[1] While it is conventional to refer to an artist by their last name, I refer to Tshibumba Kanda Matulu by his first name in this essay. This follows the scholarship on Tshibumba produced by the main expatriate anthropologists who worked with him: Johannes Fabian and Bogumil Jewsiewicki. Other scholarship on Congolese popular painting generally refers to Tshibumba by his first name.

[2] It should be noted that the version of this painting reproduced in this essay is slightly different from the version reproduced in Johannes Fabian’s Remembering the Present: Painting and Popular History in Zaire. Instead of the 1960–63 national flag, the version reprinted in Remembering the Present is replaced with the building of Kinshasa’s post office. According to Tshibumba, people organized in the square in front of the post office for public gatherings. See Fabian, Remembering the Present, p. 92.

[3] Ironically, the name “Zaïre” came from the Portuguese misunderstanding of the KiKongo word for river, which is N’zadi. Kevin Dunn points out that the choice to use Zaïre instead of N’zadi is not clear. See Dunn, Imagining the Congo: The International Relations of Identity, pp. 110–111.

[4] Tshibumba Kanda Matulu, quoted in Johannes Fabian, Remembering the Present, p. 92.

[5] Tshibumba Kanda Matulu, quoted in Johannes Fabian, Remembering the Present, p. 15.

[6] Johannes Fabian, Remembering the Present, p. xi.

[7] Tshibumba Kanda Matulu, quoted in Johannes Fabian, Remembering the Present, p. 122.

[8] Kevin Dunn, Imagining the Congo, p. 114. For a succinct retelling of Lumumba’s arrest and assassination, see Gabriella Nugent, “From camera to canvas: The case of Patrice Lumumba and Congolese popular painting,” p. 84.

[9] Sarah Van Beurden, “Congo Art Works: Popular Painting ed. by Bambi Ceuppens and Sammy Baloji (review),” p. 94.

Additional resources

Kevin Dunn, Imagining the Congo: The International Relations of Identity (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003).

Ilona Szombati-Fabian and Johannes Fabian, “Art, History, and Society: Popular Painting in Shaba, Zaire,” Studies in Visual Communication 3, no. 1 (1976): pp. 1–21.

Johannes Fabian, Remembering the Present: Painting and Popular History in Zaire (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996).

Enid Guene, “Artistic Movements: Visual Arts and Cross-Border Exchange on the Central African Copperbelt,” Journal of Southern African Studies 47, no. 6 (2021): pp. 951–972.

Adam Hoschild, King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1999).

Gabriella Nugent, “From camera to canvas: The case of Patrice Lumumba and Congolese popular painting,” Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, no. 47 (2020): pp. 82–93.

Sarah Van Beurden, “Congo Art Works: Popular Painting, ed. by Bambi Ceuppens and Sammy Baloji (review),” African Arts 51, no. 4 (2018): pp. 94–96.