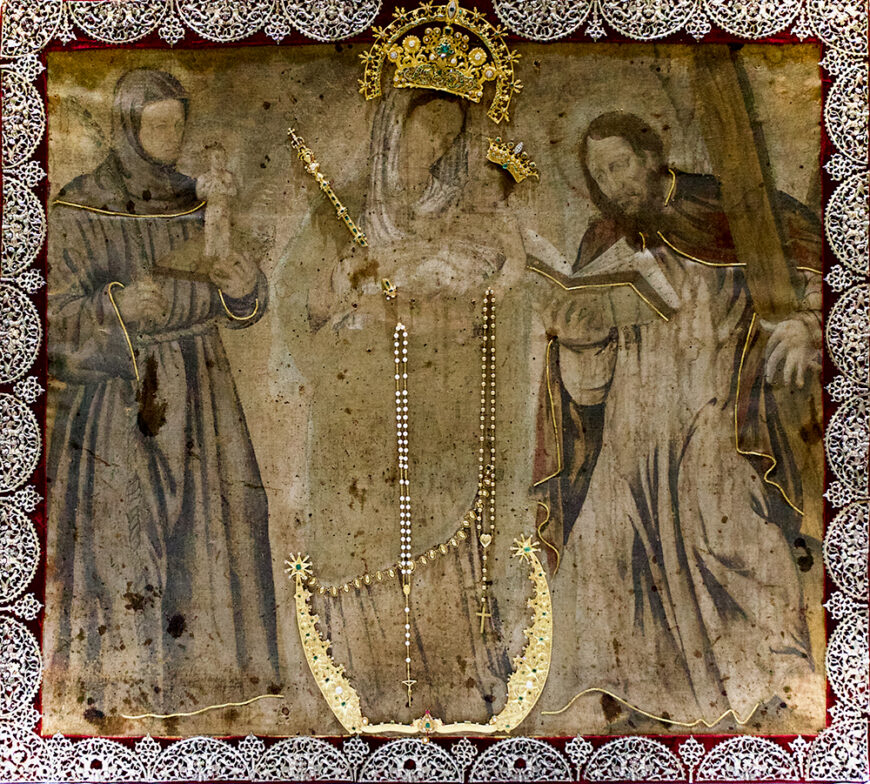

Unidentified artist, Our Lady of the Rosary of Chiquinquirá, 1743, oil and gold on silver, 11 7/8 x 11 13/16 inches (Collection of the Carl & Marilynn Thoma Foundation)

In 1743, Francisco José de Figueredo y Victoria, the newly appointed Bishop of Popayán (in what is now southern Colombia), received a remarkable gift, an image of Our Lady of Chiquinquirá set into a silver frame. The image was not painted on canvas or wood panel, or even on a sheet of copper, but on a sheet of silver. In fact, this painting is almost singular in being painted on silver—a testament to the expense involved in its creation and its important function as an impressive diplomatic gift. It is one of numerous copies made of a miraculous image painted in the 16th century.

A holy apparition

According to legend, the original image of Our Lady of the Rosary of Chiquinquirá was painted by the Spanish artist Alonso de Narváez for the encomendero (landowner) Antonio de Santana. Narváez painted the image of the Virgin of the Rosary holding the Christ Child and flanked by Saint Anthony of Padua and Saint Andrew on a length of cotton cloth made by Indigenous people known as a manta. When it was completed in 1562, Santana installed the painting on an altar in a chapel on his hacienda near the village of Suta where over time it was damaged by moisture and sunlight. After his death, Santana’s widow moved to Chiquinquirá, taking the painting with her. There, it attracted the devotion of a devout woman, María Ramos, who refurbished the oratory where the image hung and prayed fervently for its restoration. In 1586, her prayers were answered when the painting miraculously appeared with its original colors.

At nearly 500 years old, the original work has once again faded and become damaged by age and moisture. It is housed today in the purpose-built Basilica of Our Lady of the Rosary of Chiquinquirá. Alonso de Narváez, Our Lady of the Rosary of Chiquinquirá, 1562, tempera on cloth (Basilica of Our Lady of the Rosary of Chiquinquirá, Colombia)

After its miraculous restoration, the image began to attract pilgrims and quickly became one of the most important Marian advocations in New Granada—and remains a popular devotion in Colombia today. Numerous copies of the miraculous image were made in prints, paintings, and even small domestic altars for private devotion.

Unidentified artist, Our Lady of the Rosary of Chiquinquirá, 1743, oil and gold on silver, 11 7/8 x 11 13/16 inches (Collection of the Carl & Marilynn Thoma Foundation)

The painting on silver follows the typical iconography of images of Our Lady of Chiquinquirá and features the palette of bold reds and blues often found in the painting of Quito (in present-day Ecuador) where this work was created. Quito was one of the main artistic centers in the Viceroyalty of New Granada, and was renowned not only for painting but also for the high-quality sculpture produced there.

At left stands Saint Anthony of Padua with the Christ Child and at right Saint Andrew, holding a cross and reading from a book. At the center is the Virgin Mary, standing on a crescent moon. In her arms she holds the Christ Child, on whose fingers rests a red songbird, and a rosary. In her other hand she holds a scepter as two putti swoop down to crown her, indicating her status as the Queen of Heaven. The delicately-rendered figures all have large eyes, a feature found in some examples of Quiteño painting. The sparing application of gold found on the edges of the robes, halos, and attributes of the two saints are also a hallmark of 18th-century Quito painting.

Unidentified artist, Our Lady of the Light, late 18th century, oil and gold on canvas, 27 1/2 x 19 5/8 inches (Collection of the Carl & Marilynn Thoma Foundation)

Monstrance (1700–27), workshop of Quito. Muy Antigua, Pontificia, Real e Ilustre Hermandad Sacramental de Nuestra Señora de las Angustias (Granada, Spain)

Silver in Quito

Though painting on silver surfaces was quite unusual, Quito was nevertheless an important center of silver production. Thanks to mines scattered throughout the Audiencia of Quito, the production of silver and gold objects (known respectively as platería and orfebrería) began in the 16th century. The earliest artists came from Spain and Portugal and then Indigenous artists joined their workshops, some bringing knowledge of pre-contact smithing techniques. Unsurprisingly, the Church was the largest consumer of colonial platería and commissioned silver objects for the adornment of churches and monasteries. Among these were objects used in the liturgy such as chalices, patens, incense burners, and book stands as well as monstrances to display the eucharistic host.

Additionally, artists made silver frames to adorn especially precious objects, like this image of the Virgin of Mercy painted on a sheet of hammered copper. Objects like this were intended for private devotion, and during the 18th century, became important luxury goods as artists competed to produce finely wrought devotional images for their clients. [1]

Unidentified artist, Virgen mercedaria de la Misericordia, 18th century, oil on copper, 43 x 44 cm (Museo Nacional del Banco Central de Ecuador, Quito)

Surrounding both artworks are elaborate rococo frames which were popular in the 18th century, particularly in Quito. Both feature rocaille or rocalla detailing, an artistic style that imitates the forms of rocks, pebbles, shells, and vegetation. The ornamentation along the top of the silver frame surrounding Our Lady of Chiquinquirá recalls a cresting wave or the delicate edge of a flower petal.

A prince of the Church

Figueredo, Bishop of Popayán, was particularly dedicated to Our Lady of Chiquinquirá, making a pilgrimage over difficult roads to visit the miraculous image during his years as a rural cleric: “he increased the riches of the image, whose portrait he never separated from himself, and whose name was always heard on his lips with tenderness and fires of the heart.” The iconography was likely chosen by the Jesuits, who commissioned the image, to represent one of Figueredo’s most cherished devotions. The image was a strategic gift from the Jesuit Order—specifically tailored to Figueredo and made in costly materials—in the hopes of securing his favor.

Figueredo had a long relationship with the Order; he had been educated at the Jesuit College of San Luis in Quito, where he received a doctorate in Theology, and it was likely this experience that endeared him to the Order. He spent the early years of his career as a rural cleric and later an ecclesiastical official in Popayán. In 1741 Figueredo was elevated to Bishop of Popayán with the aid of influential Jesuits in Spain. The Jesuits were savvy political operators, who often sought to install members in positions of power. Figueredo was officially inaugurated in Quito in 1743, perhaps the occasion on which he received this sumptuous gift from the Order that had helped educate him and elevate him to ecclesiastical office.

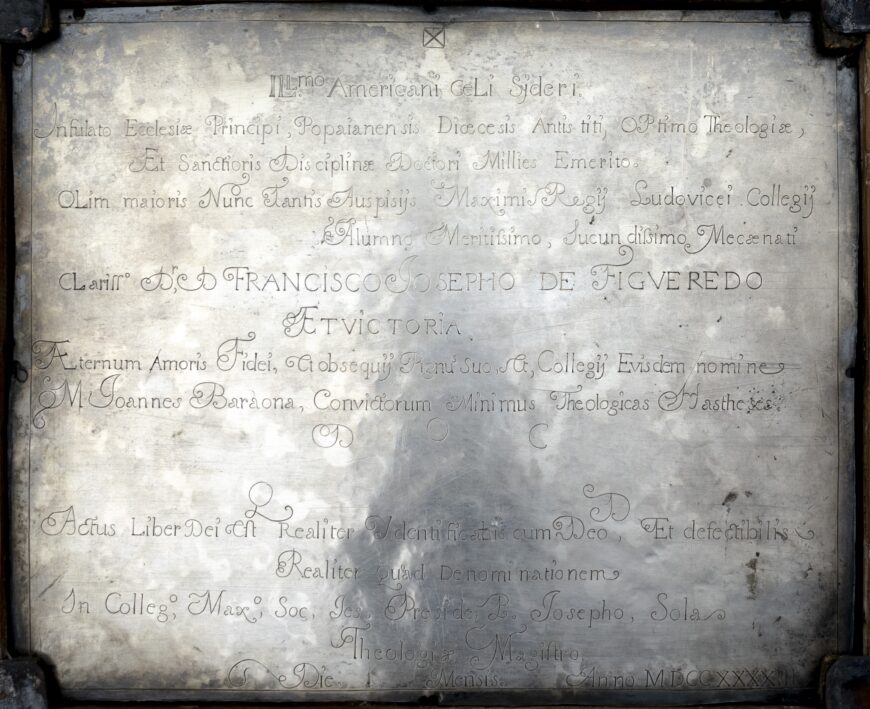

Reverse, unidentified artist, Our Lady of the Rosary of Chiquinquirá, 1743, oil and gold on silver, 11 7/8 x 11 13/16 inches (Collection of the Carl & Marilynn Thoma Foundation)

The reverse of the silver plate carries an inscription acknowledging Figueredo’s patronage of the Jesuit Order during his ecclesiastical career. The inscription panel praises him in the highest terms, referring to him as the “brightest star of the American sky” and “a most distinguished doctor of moral and sacred theology, who earned his title a thousand times over.” [2] It also notes Figueredo’s patronage of the College, which perhaps increased after such a splendid gift, as the Jesuits sought to further cultivate their relationship with an alumnus holding an important ecclesiastical position.

Figueredo’s close relationship with the Jesuits would last throughout his years as Bishop of Popayán and the Order was also instrumental in seeing him appointed as Archbishop of Guatemala in 1751. During his tenure in Guatemala alone, Figueredo funneled over 40,000 pesos to the Order. [3] On his deathbed in 1765, Figueredo had himself ordained as a Jesuit and his funeral mass was celebrated not only at the Cathedral but also at the Jesuit Church in Guatemala City.

It was only two years after Figueredo’s death, in 1767, that the Jesuits would be expelled from the Spanish realms. The Order had already been expelled from other lands at this point—including France and the Portuguese Empire. The expulsion was brought about in part because of the Bourbon Reforms which sought to secularize and modernize colonial administration—consequently lessening the influence of the Vatican and the religious orders closest to it. Additionally, the Spanish crown was unhappy with the great wealth that the Jesuit Order had amassed—in part through donations from influential figures like Figueredo. In fact, his largesse toward the Order brought Figueredo under the suspicion of the Council of the Indies, the supreme administrative and judicial body of the Spanish empire. [4]

The painting is a physical manifestation of the kind of gift diplomacy engaged in by the Jesuits at a time of tremendous wealth and power for the Order. Given Figueredo’s continued patronage of the Jesuits, their efforts seem to have been a success.

This diminutive but sumptuous object is an important record of the kinds of power brokering that took place during the colonial period between religious orders and the figures they sought to influence. This painting was used as a means to flatter the receiver and, by catering to his specific devotional preferences, may have done significant work to endear the Jesuits to Figueredo and maintain their ties to figures in power.

Notes:

[1] Suzanne L. Stratton-Pruitt, editor, The Art of Painting in Colonial Quito (Philadelphia: St. Joseph’s University Press, 2012), p. 232.

[2] Translation courtesy Erika Valdivieso.

[3] Carmelo Sáenz de Santamaría, “La vida económica del colegio de los jesuitas en Santiago de Guatemala,” Revista de Indias 37 (1977), p. 556.

[4] Carmelo Sáenz de Santamaría, “La vida económica del colegio de los jesuitas en Santiago de Guatemala,” Revista de Indias 37 (1977), p. 556.

Additional resources

Luis Navarro García and Fernando Navarro Antolín, Las dobles exequias del arzobispo Figueredo (1765): El canto del cisne de los jesuitas en Guatemala (Huelva: Universidad de Huelva, 2016).

Nancy P. Morán Proaño, “El lucimiento de la fe. Platería religiosa en Quito,” in Arte de la Real Audiencia de Quito, siglos XVII-XIX, edited by Alexandra Kennedy (Quito: Editorial Nerea, 2002), pp. 145–61.

Carmelo Sáenz de Santamaría, “La vida económica del colegio de los jesuitas en Santiago de Guatemala,” Revista de Indias 37 (1977).

Suzanne L. Stratton-Pruitt, editor, The Art of Painting in Colonial Quito (Philadelphia: St. Joseph’s University Press, 2012).