Test your knowledge with a quiz

Woodville War News

Key points

- Anglo-American belief in Manifest Destiny served to justify the U.S. government’s efforts to claim new territories.

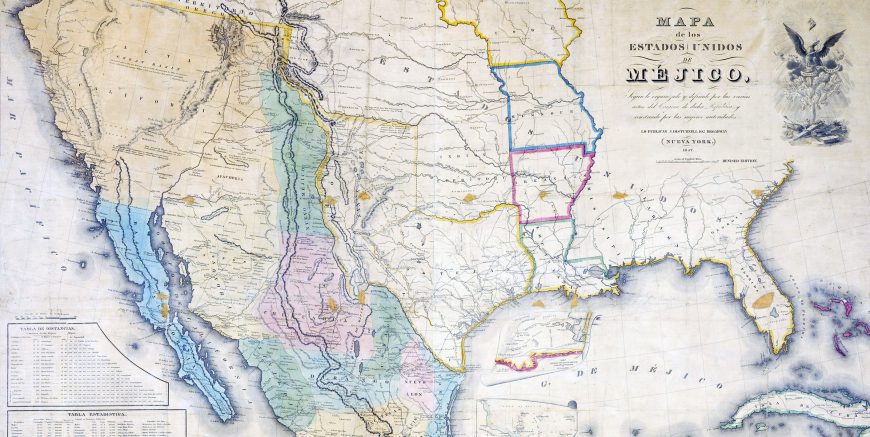

- The 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the Mexican-American War, resulted in the Mexican Cession of what is now the southwestern United States, including parts of what are now Arizona, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, California, Wyoming and Colorado.

- The conflict in the 1840s over whether new territories should enter the U.S. as free or slave states foreshadowed the national division over slavery that led to the Civil War.

- New technologies such as the newspaper and telegraph speeded communication, connected the growing nation, and helped shape the public’s response about current events.

- Woodville’s politically ambiguous image had broad popular appeal.

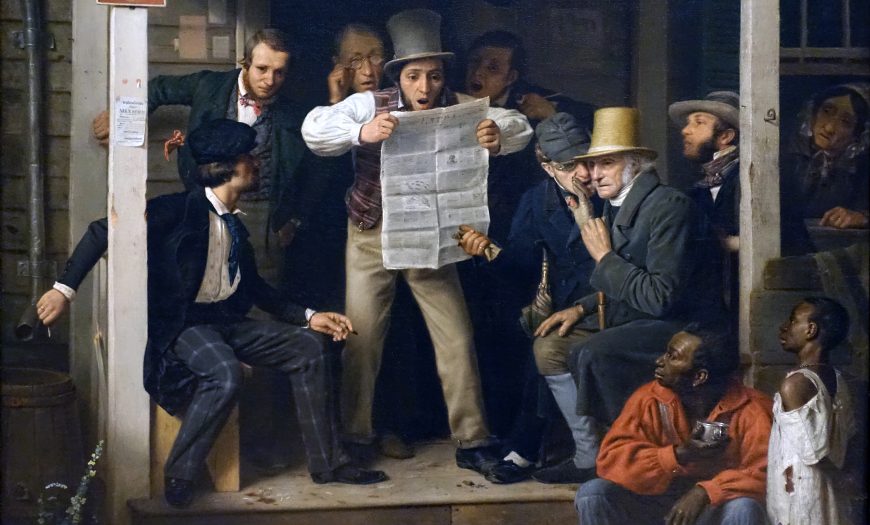

Richard Caton Woodville, War News from Mexico, 1848, oil on canvas, 68.6 × 63.5 cm (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas)

A crowd gathered for the news

The young man in the center of a crowd in Richard Caton Woodville’s War News From Mexico (1848) holds open a newspaper with his elbows up, but the paper is low enough that we can see the astonished look on his face.

Map of Mexico, color-filled areas show Mexican territory in 1847. The yellow and green areas at the top left became part of the southwestern United States in 1848.

Volunteer Flyer (detail), Richard Caton Woodville, War News from Mexico, 1848, oil on canvas, 68.6 × 63.5 cm (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas)

And the news itself? As the title indicates, this is a dispatch from the front of the Mexican-American War. United States troops entered Mexico City in 1848, bringing to an end a war that had begun in 1846 over a territorial dispute involving Texas. In the resulting Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Mexico ceded half its territory to the United States, effectively concluding the U.S. program of westward expansion.

To convey the characteristics of a Western outpost, the men gathered in the painting are shown standing on the porch of a building typical of the kind erected in the American frontier during the rush for territories in the early decades of the nineteenth century. In fact, the building serves multiple functions: it is both an “American Hotel” and post office, as indicated on the signs. While the building emulates in wood the style of stone classical structures found in Philadelphia or New York City, the artist has taken great care with the details to remind the viewer this is on the frontier: the wood is worn, and underneath the “post office” sign is tacked a recruitment notice asking for “Volunteers for Mexico!”

A range of responses

Opinion on the war was divided and Woodville thus depicts a range of responses. An older man in Revolutionary-era clothing just to the right of the standing figure holding the newspaper, strains to hear as another repeats into his ear what is being read. One young man in the background is tossing his hat into the air; he clearly welcomes the news but the seated elder shows far less enthusiasm. His outdated clothing identifies him as part of the generation that fought the Revolutionary War but did not endorse the expansion embraced by the new Jacksonian-era democracy. And what of the inhabitants themselves of the former Spanish colonies in the southwest (Mexico had gained independence from Spain in 1821)? This could only be bad news; the surrendering of territory spelled the loss of cultural identity. A protestant, Anglo-American culture, pushing westward, acquiring new states for the Union, would seek to eradicate any vestiges of Hispanic-Catholic identity. Mexicans would wake up the day after the treaty was signed and find themselves second-class citizens in a new country.

Porch (detail), Richard Caton Woodville, War News from Mexico, 1848, oil on canvas, 68.6 × 63.5 cm (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas)

Genre scenes

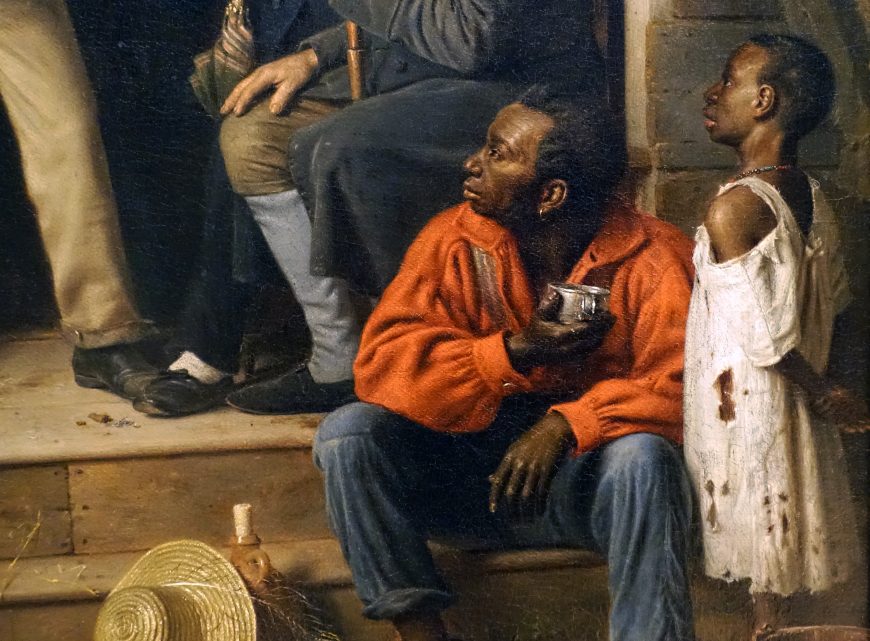

American genre-scene painters during this period typically strove to represent an array of social types in their rapidly modernizing nation, and Woodville’s painting is no exception (“genre” paintings depict scenes of everyday life). There were often humorous illustrations of class status or newly immigrant Americans in genre scene paintings but they also betrayed, in equal measure, social anxiety about a shifting demography in a new political environment. There are African-American figures in the painting but they are pushed to the border, outside the framing beams of the hotel’s portico—a seated man in a bright orange shirt and a child wearing a tattered white dress. They look on from the bottom right, at the foot of the steps, but their facial expressions seem to register only weariness or perhaps resignation. The question as to whether the new territories would be slave states or free ones was hotly debated—some saw the war as extending the institution of slavery—and Woodville nods to this larger political reality. There is also an elderly woman barely visible in the shadows; she leans out a window and looks in the direction of the group on the porch. These figures are not included within the immediate circle of white men—perhaps suggesting their less central position within society.

Man and child, lower right (detail), Richard Caton Woodville, War News from Mexico, 1848, oil on canvas, 68.6 × 63.5 cm (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas)

Images of frontier life were popular in the years leading up to the Civil War and Woodville had great success depicting this kind of everyday subject matter. He specialized in domestic interiors—an important subset of this newly emergent category of genre-scene painting. This subject type was popular in Europe (particularly during the 17th century in the Dutch Republic), however it was a relatively new phenomenon in American art—reaching its height of popularity in the period that stretched from the 1830s through the Civil War of 1861-65. Genre scene paintings were aimed at a broadly expanded and increasingly literate middle-class whose tastes ran to familiar scenarios of everyday life, rather than the mythic or historical themes favored by the art academies (the Royal Academies of Europe and the National Academy in the United States). Genre-scene paintings were promoted by organizations like the American Art Union (AAU). The AAU was formed in 1839 to promote American artists and specifically to forge a uniquely American art. Once exhibited under the aegis of the AAU—Woodville’s War News From Mexico was exhibited in 1849 right after the war ended—paintings were then turned into engravings and sold to AAU members by subscription.

Woman in window (detail), Richard Caton Woodville, War News from Mexico, 1848, oil on canvas, 68.6 × 63.5 cm (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas)

In contrast to the marginalized figures of the woman and the African Americans, the newspaper takes pride of place in this painting. The “penny presses,” as they were called, a relatively recent invention, were mass-produced commercial newspapers that emerged in the 1830s during a period of rapid industrialization and modernization. Unlike their more expensive, subscription-based counterparts, the penny presses (so named because they cost mere pennies) reached a broad swath of the American public. Not only was the Mexican-American War one of the very first to be photographed, it was also extensively broadcast through print—through the very type of paper depicted in the painting, with its top banner emblazoned with the words “EXTRA.” The newspaper, in fact, functioned as a powerful symbol of the power of the press to bring Americans together and the painting suggests the role of the paper in shaping public opinion.

Newspaper (detail), Richard Caton Woodville, War News from Mexico, 1848, oil on canvas, 68.6 × 63.5 cm (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas)

Genre-scene paintings often conveyed a sense of immediacy and here War News From Mexico orients itself towards the viewer in such a way that one feels as if one has just stumbled upon the scene. Notice, for example, how the perspective is tilted to the right of the viewer; this has the effect of positioning us off to the left side as if we have just come around some imaginary corner and the American Hotel, its porch crowded with the town’s inhabitants, careens into view.

Manifest Destiny

Despite this seeming spontaneity, War News from Mexico is as carefully composed and even as moralizing as the staid history paintings and Neoclassical subjects favored by the academies. Though it was commonplace to view genre-scene paintings as “snapshots” of daily American life without larger purpose, this unfolding scene (meant to indicate some place on the frontier far removed from the military action, but close enough that it mattered), takes place against the backdrop of Manifest Destiny—the theory that drove and justified westward expansion.

The ideology of Manifest Destiny construes Anglo-Americans as God’s chosen people who—like the ancient Israelites of the Old Testament—are guided by God to their destiny. This was a subject often depicted in painting. For example, in Emmanuel Leutze’s mural for the west stairway of the U.S. Capitol, Westward the Course of Empire Takes its Way, we see American pioneers and their covered wagons looking towards the sunset and the Pacific Ocean while one of the scenes in the lower right border (illustrated left) depicts Moses leading the Israelites through the desert.

Emanuel Leutze, Westward the Course of Empire Takes its Way, 1862, stereochrome, 6.1 × 9.1 m (United States Capitol, Washington, D.C.)

Beginning with the American Revolution, this American “exceptionalism” (as it also came to be known), rationalized not only the acquisition of land all the way to the Pacific Ocean, but also the subjugation and removal of people from their land—the Indian Removal Act of 1830 that President Andrew Jackson signed into law strengthened the rapid acquisition of land that went hand in hand with expulsion and extermination.

Woodville makes no overt statement of his politics in War News from Mexico but his painting nevertheless encapsulates a larger history than the scale of this relatively small painting (it measures approximately 27 x 25 inches) would seem to allow. If War News from Mexico does, however ambiguously, extol the ideology of Manifest Destiny and the inevitability of America’s domination of a large part of the continent, it is an ironic fact of history that Woodville’s scenes of life in the American West were painted while he lived in Europe. Born in Baltimore, Woodville left for Europe as a young man to train in Düsseldorf, Germany, and remained abroad until his death in London at the age of 30.

Go Deeper

Learn more about this painting from the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

How did the Mexican-American War reshape America’s international standing?

What was the role of President Polk in westward expansion?

How did Texas become a part of the United States?

How did the media affect the public response to the Mexican-American War?

How did artists represent scenes of everyday life in nineteenth-century America?

More to think about

If the scene depicted in War News from Mexico represented life today, how would you populate the image? Who would be on the porch? The steps? Inside the house? On the periphery?

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”WarNews,”]