videos + essays

Donatello, Feast of Herod

City-states vied for the best artists. After Ghiberti dragged his feet, Siena invited Donatello to finish the job.

Donatello, David

His nudity references classical antiquity, but David embodies the ideals and concerns of 15th-century Florence.

Filippo Brunelleschi and Lorenzo Ghiberti, Sacrifice of Isaac

Brunelleschi’s panel may be scarier, but Ghiberti’s is more emotionally complex. In both, an angel saves the day.

Michelangelo, David

Where’s Goliath? David scans for his enemy. This colossal sculpture is itself a giant of 16th-century Renaissance art.

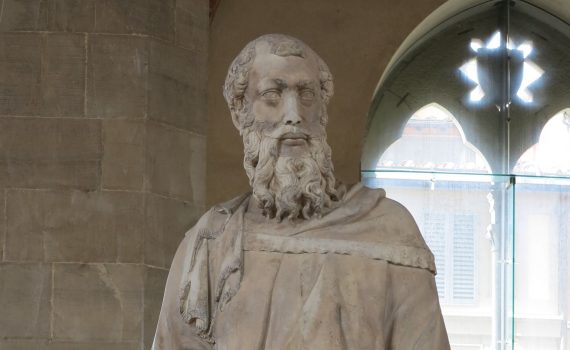

Donatello, St. Mark

When the citizens of Florence looked up at St. Mark, they saw a mirror of their own dignity—and of ancient nobility.

Lorenzo Ghiberti, Gates of Paradise, East Doors of the Florence Baptistry

These gilded bronze doors are a masterpiece of clarity and illusionism. Space coheres, and figures move with ease.

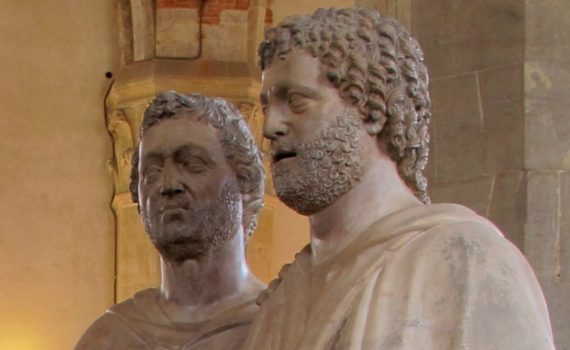

Nanni di Banco, Four Crowned Saints

Capturing figures in thought, stonemasons understood what it meant to be human—just like the ancient Romans.

Donatello, Mary Magdalene

This difficult sculpture is an exercise in contrasts: frailty and power, pure spirituality and anatomical accuracy.

Donatello, Madonna of the Clouds

This marble relief is as flat as Tuscan bread, yet its atmospheric space recedes into depth. Extraordinary.

Orsanmichele and Donatello’s Saint Mark, Florence

From granary to—church? Once open to the city, this building and its niches blend the spiritual with the everyday.

Michelangelo, Pietà

Can stone be that soft? Contrast defines this sculpture. Mary is sweet but strong, and Christ, real yet ideal.