Curated Guides > Syllabus > Medieval and Byzantine Art and Architecture Syllabus

Medieval and Byzantine Art and Architecture Syllabus

Once described as a “dark age” between the ancient and modern periods, the “Middle Ages” (c. 3rd–14th centuries C.E.) is now understood as a dynamic era of emerging religious identities, cross-cultural encounters, and creative production of soaring architectural forms and sumptuous works of art.

What is medieval art and how did it all begin? During the 3rd–5th centuries, Greco-Roman, Jewish, and Christian cultures interacted in surprising ways: building architectural spaces for civic and religious activities and producing artworks to convey beliefs, construct identities, and memorialize the dead.

Relief panel with The Spoils of Jerusalem Being Brought into Rome, Arch of Titus, Rome, after 81 C.E., marble, 7 feet 10 inches high

- Jewish art

- Judaism, an introduction

- The Synagogue at Dura-Europos

- Mosaic decoration at the Hammath Tiberias synagogue

- Early Christian art

- Christianity, an introduction

- Santa Maria Antiqua Sarcophagus

- Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus

- The Good Shepherd in Early Christianity

- Constantine and the Roman basilica

- Colossus of Constantine

- Basilica of Constantine (Aula Palatina), Trier

- The origins of Byzantine architecture

- Basilica of Santa Sabina, Rome

- Santa Pudenziana

- What functions did artistic representations serve in late antique Jewish synagogues?

- How did Christians appropriate and adapt Greco-Roman art?

- What can funerary art tell us about people of the past?

- How did the legalization of Christianity and imperial patronage impact Christian art and architecture in the Roman Empire?

- What are some of the key characteristics of a basilica?

- synagogue

- Torah shrine

- mosaic

- tesserae

- sarcophagus

- house church

- baptistery

- catacomb

- basilica

- aisle

- nave

- apse

- altar

- clerestory

- martyrium (plural: martyria)

Key Questions

Key Terms

After the Roman emperor Constantine established Constantinople as a new capital in the 4th century, the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire expanded to its greatest extent by the 6th century. Glittering mosaics, richly decorated manuscripts, and innovative church architecture abound in 6th-century Constantinople, the Italian city of Ravenna, and the Sinai peninsula, proclaiming Christian belief and the authority of the Roman emperor.

Isidore of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles for Emperor Justinian, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (Istanbul), 532–537 C.E. (photo: © Robert G. Ousterhout)

- Introduction

- About the chronological periods of the Byzantine Empire

- Early Byzantine architecture and its decoration

- Constantinople (Turkey), the New Rome

- SS. Sergius and Bacchus, preserved as the mosque, Küçük Ayasofya

- Hagia Sophia, Istanbul

- Ravenna (Italy)

- Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna

- San Vitale and the Justinian and Theodora Mosaics

- Empress Theodora, rhetoric, and Byzantine primary sources

- Mount Sinai (Egypt)

- Art and architecture of Saint Catherine’s Monastery at Mount Sinai

- Early Byzantine art

- Wearable art in Byzantium

- Ivory Panel with Archangel

- Icon with Virgin (Theotokos) and Child between Saints Theodore and George

- The Story of Jacob from the Vienna Genesis

- The Vienna Dioscurides

- What architectural innovations can be observed in churches from 6th-century Constantinople?

- How do the mosaics of Ravenna reflect political and religious conflicts between the Byzantines and the Ostrogoths?

- Why was Saint Catherine’s Monastery located where it was?

- In what ways was Early Byzantine art similar to and different from the classical art of the ancient Greco-Roman world that preceded it?

- What functions did jewelry and other bodily adornments serve in the Byzantine world, and how was it similar or different from today?

- central plan

- dome

- pendentive

- column

- pier

- capital

- revetment

- procession

- Eucharist

- martyr

- triumphal arch

- impost block

- Ostrogoth

- Arian

- orthodox

- folio

- Exodus

Key Questions

Key Terms

The 7th century saw the emergence of Islam on the Arabian Peninsula and its rapid expansion into much of what had been the Roman Empire. The Islamic Umayyads built on Roman foundations to construct glorious new monuments, while the Iconoclastic Controversy—characterized by fierce debates over religious images—shook the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) capital of Constantinople.

Courtyard of the Great Mosque of Damascus (photo: Eric Shin, CC BY-NC 2.0)

- Islam

- Islam, an introduction

- About chronological periods in the Islamic world

- Introduction to mosque architecture

- Common types of mosque architecture

- The Umayyads

- The Umayyads, an introduction

- The Dome of the Rock (Qubbat al-Sakhra)

- The Great Mosque of Damascus

- Mosaics in the early Islamic world

- Exchange and iconoclasm

- Cross-cultural artistic interaction in the Early Byzantine period

- Icons, an introduction

- Byzantine Iconoclasm and the Triumph of Orthodoxy

- The Byzantine Fieschi Morgan cross reliquary

- How did Umayyad art and architecture reflect and communicate the emergent beliefs of the Islamic faith?

- How are Umayyad mosaics similar to and different from Byzantine mosaics?

- How was ancient Roman architecture reused in Christian and Islamic contexts?

- What is an icon?

- Who were the key players and what were the central disagreements of the Iconoclastic Controversy?

- Mecca

- Kaaba

- Qur’an

- caliph

- mosque

- Haram al-Sharif

- Silk Roads

- icon

- Iconoclastic Controversy

- iconoclast

- iconophile

- Triumph of Orthodoxy

- True Cross

- relic

- reliquary

Key Questions

Key Terms

Meanwhile in western Europe as Roman political structures were weakening, the migration of Germanic peoples and the rise of Christianity fused disparate cultural forms to produce precious books, intricate jewelry, and other decorative arts during the Early Medieval period. From the 8th–11th centuries, seafaring Scandinavians produced complex artworks that mingled pagan and Christian imagery in the art of the Viking Age.

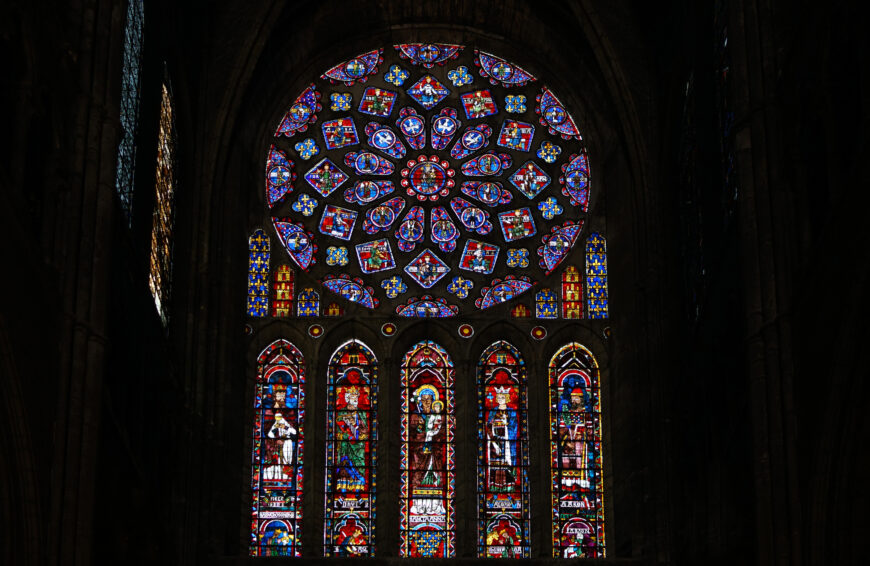

North Transept Rose Window, Cathedral of Notre Dame de Chartres, France, c. 1145 and 1194–c. 1220

- Instability in the Early Medieval period

- Introduction to the Middle Ages

- Fibulae

- Anglo-Saxon England

- Early Medieval art of the British Isles

- Sutton Hoo Ship Burial

- The Lindisfarne Gospels

- Codex Amiatinus, the oldest complete Latin Bible

- The Book of Kells

- The Ardagh Chalice

- Skellig Michael

- Muiredach Cross

- Clonmacnoise

- Viking art

- Art of the Viking Age

- What are the objects of the Sutton Hoo Ship Burial and what can they tell us about the person who was buried there?

- What roles did monasteries play in the Early Medieval period?

- How were images and ornament fused in fibulae, bibles, and other Early Medieval artworks?

- What features and motifs characterize the different styles of the Viking Age?

- fibula (pl. fibulae)

- cloisonné

- Anglo-Saxon

- Hiberno-Saxon

- garnet

- chalice

- monastery

- scriptorium

- illuminated manuscript

- Gospel

- evangelist

- carpet page

- interlace

- filigree

- canon table

- Chi Rho

Key Questions

Key Terms

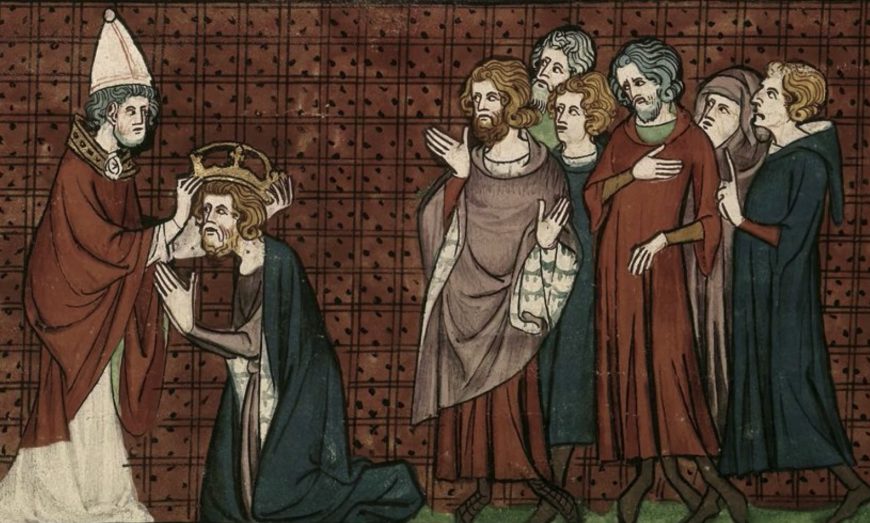

When Charlemagne, who controlled much of western Europe including what is now France and Germany, was crowned emperor by the pope in 800, he laid claim to the legacy of the Roman Empire. The art and architecture of his Carolingian dynasty reflected these Roman aspirations, as did the later Ottonian dynasty, whose rulers fashioned themselves as “Holy Roman Emperors.”

Charlemagne crowned Emperor on Christmas Day, 800, in the second book of Charlemagne's life in Les Grandes Chroniques de France, c. 1332–50 (British Library, London, Royal MS 16 G VI, folio 141 verso)

- Carolingian art

- Charlemagne (part 1 of 2): An introduction

- Charlemagne (part 2 of 2): The Carolingian revival

- Palatine Chapel, Aachen

- Matthew in the Coronation Gospels and Ebbo Gospels

- The Utrecht Psalter and its influence

- Lindau Gospels cover

- Depicting Judaism in a medieval Christian ivory

- Ottonian art

- Ottonian art, an introduction

- Gospel Book of Otto III

- Cross of Lothair II

- Bronze doors, Saint Michael’s, Hildesheim (Germany)

- Bronze Casting Using the “Lost Wax” Technique

- In what ways did the Carolingians seek to revive stylistic forms and other cultural elements from the ancient Roman world?

- What is spolia and how did the Carolingians and Ottonians use it to construct a Roman imperial identity?

- What is the “Heavenly Jerusalem” and how did Carolingian artists use different materials to evoke it?

- What is lost-wax casting and what role did it play in Ottonian art?

- What are “Ecclesia” and “Synagoga” and what were they meant to represent?

- Franks

- Lombards

- Heavenly Jerusalem

- lost wax casting

- classical, classicizing

- Psalter

- Christological

- ivory

- Acanthus

- personification

- Ecclesia and Synagoga

- spolia

- Carolingian

- Ottonian

Key Questions

Key Terms

In the 9th century, the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire bounced back from the Iconoclastic Controversy and artistic and cultural production flourished once again. Kyivan Rus’—a powerful confederation of city-states in eastern Europe—allied with the Eastern Romans and emulated Byzantine art and architecture. While in Sicily, a new kingdom established by the Normans, who emerged during the Viking Age, appropriated both Eastern Roman and Islamic cultural forms to announce themselves as a new power in the Mediterranean region.

Narthex mosaic over Imperial Door, c. 900, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

- Middle Byzantine art

- A work in progress: Middle Byzantine mosaics in Hagia Sophia

- The Paris Psalter

- A Byzantine vision of Paradise — The Harbaville Triptych

- Icon of the Archangel Michael

- Mosaics and microcosm: the monasteries of Hosios Loukas, Nea Moni, and Daphni

- Byzantine frescoes at Saint Panteleimon, Nerezi

- Middle Byzantine secular art

- The influence of Byzantium beyond its borders

- Byzantium, Kyivan Rus’, and their contested legacies

- Saving Torcello, an ancient church in the Venetian Lagoon

- The visual culture of Norman Sicily

- The Cappella Palatina

- How did the end of the Iconoclastic Controversy impact the decoration of Middle Byzantine churches?

- What artistic interventions were made in Hagia Sophia in Constantinople following the end of Iconoclasm and how did they change this cathedral?

- What non-religious objects were produced in the Middle Byzantine period and how were they decorated and used?

- What was the relationship between architecture and monumental art (e.g. mosaics and frescoes) in Middle Byzantium, Kyivan Rus’, and Norman Sicily?

- How did the Normans appropriate and blend Eastern Roman and Islamic cultural forms to construct identity and project power in Sicily?

- gallery

- naturalistic

- Deësis

- pseudo-Arabic

- Intercession

- relief

- repoussé

- chasing

- Christ Pantokrator

- orans

- Annunciation

- Romanesque

- muqarnas

Key Questions

Key Terms

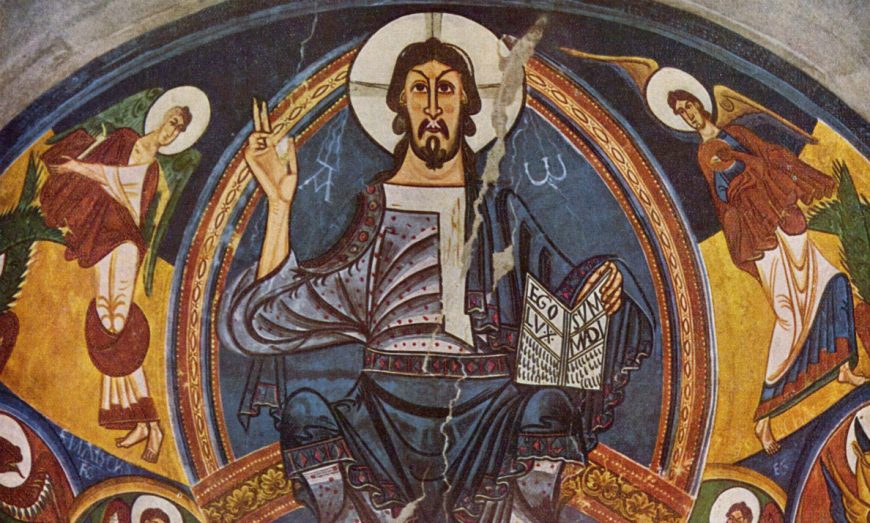

Master of Taüll, apse painting, Sant Clement in Taüll, c. 1123 (Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya, Barcelona)

- Introduction

- A beginner’s guide to Romanesque art

- England and the Norman Conquest

- The Art of Conquest in England and Normandy

- Durham Cathedral

- Peterborough Cathedral

- The English castle: dominating the landscape

- Ireland

- Saint Patrick’s Bell and Shrine

- The Cross of Cong

- Cormac’s Chapel

- Italy and Spain

- The Romanesque churches of Tuscany: San Miniato in Florence and Pisa Cathedral

- Basilica of Sant’Ambrogio, Milan

- The Basilica of San Clemente, Rome

- The Painted Apse of Sant Climent, Taüll, with Christ in Majesty

- What was the Norman Conquest and how did it change the landscape of England?

- What are some of the key characteristics of Romanesque architecture?

- How does the Romanesque draw from ancient Roman architecture?

- What is Anglo-Norman architecture?

- decorative arts

- tapestry

- embroidery

- arch

- barrel vault

- groin vault

- lozenge

- chevron

- high cross

- campanile

- fresco

- mandorla

- alpha and omega

Key Questions

Key Terms

In the middle ages, pilgrims traveled long distances to visit sacred places like the Holy Land and to venerate holy relics. In France, and elsewhere in Europe, Romanesque churches and accompanying sculptures of the Last Judgment and other religious subjects sprang up along pilgrimage routes, attracting pilgrims and facilitating powerful encounters with the divine.

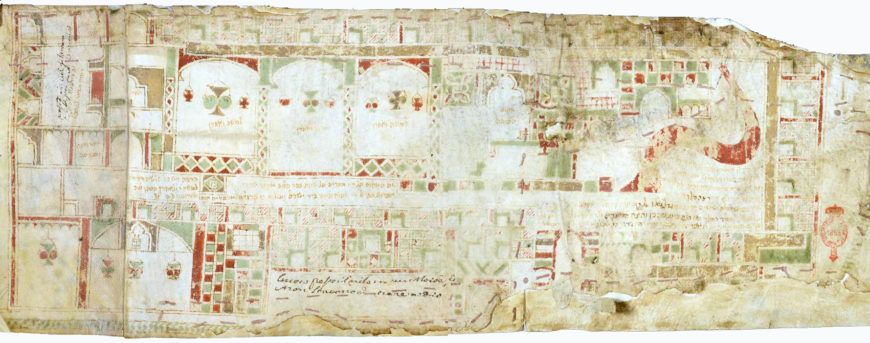

Kanisat Musa, Florence, BNC, Ms. Magl. III, 43

- Pilgrimage

- Pilgrimage souvenirs

- Pilgrimage routes and the cult of the relic

- French pilgrimage churches

- Church and Reliquary of Sainte-Foy, France

- Basilica of Saint-Sernin

- Pentecost and Mission to the Apostles Tympanum, Basilica Ste-Madeleine, Vézelay (France)

- Last Judgment, Tympanum, Cathedral of St. Lazare, Autun (France)

- Church of Saint Pierre, Moissac

- Romanesque art in France

- Casket with troubadours

- Manuscript production in the abbeys of Normandy

- “Throne of Wisdom” sculptures

- What was pilgrimage and why did medieval pilgrims undertake pilgrimage?

- What were pilgrimage souvenirs, what forms did they take, and what functions did they serve?

- How did the design of Romanesque churches accommodate pilgrimage practices?

- How were the portals of Romanesque churches decorated and why?

- What are some of the different ways that Christ and the Virgin Mary were depicted in Romanesque art?

- Holy Land

- ampula (pl. ampullae)

- Hajj

- Santiago de Compostela

- Way of Saint James

- scallop shell

- ambulatory

- transept

- crossing

- radiating chapels

- portal

- tympanum

- Last Judgment

- Throne of Wisdom

Key Questions

Key Terms

The Mediterranean was a crossroads of peoples, religions, and cultures that came into contact through trade, war, and other circumstances. Borrowed architectural forms and displaced objects circulating because of the Crusades tell dramatic stories of cross-cultural encounters and exchange of precious goods around the medieval Mediterranean.

Salón Rico, Madinat al-Zahra, Córdoba, Spain (photo: Zarateman, CC BY-SA 3.0 ES)

- Islamic Spain

- The vibrant visual cultures of the Islamic West, an introduction

- The Great Mosque of Córdoba

- Camel from San Baudelio de Berlanga

- The Fatimids and the Byzantines

- The beginnings of Cairo, the city victorious

- Rock crystal ewer, San Marco

- Cross-cultural artistic interaction in the Middle Byzantine period

- Mobility and reuse: the Romanos chalices and the chalice with hares

- The crusades

- What were the crusades?

- The Melisende Psalter

- Byzantine Art and the Fourth Crusade

- Icon with the Virgin Hodegetria Dexiokratousa

- Venice’s San Marco, a mosaic of spiritual treasure

- Plunder, war, Napoleon and the Horses of San Marco

- What is cross-cultural exchange and where do we see it in the art and architecture of the 10th–13th centuries?

- How were objects moved from one place to another in the medieval world?

- How were precious objects repurposed in the medieval world?

- What were the crusades and how did they facilitate cross-cultural interactions?

- cross-cultural exchange

- al-Andalus

- horseshoe arch

- mihrab

- Abbasids

- Fatimids

- Ayyubids

- minaret

- rock crystal

- ewer

- church treasury

- crusades

- Roman Catholic

- Orthodox

- plunder

Key Questions

Key Terms

Born in the area around Paris in the 12th century, Gothic architecture employed innovative architectural features, such as flying buttresses, to create towering new structures that were all about light. Gothic France produced new forms of illuminated manuscripts and elegant sculptures of the Virgin Mary, whose body displayed the characteristically graceful “Gothic sway.”

Ambulatory, Basilica of Saint Denis, Paris, 1140–44

- Gothic architecture in France

- Birth of the Gothic: Abbot Suger and the ambulatory at St. Denis

- Before the fire: Notre Dame, Paris

- Cathedral of Notre Dame de Chartres

- Reims Cathedral

- Amiens Cathedral

- Sainte-Chapelle, Paris

- Gothic art in France

- Bible moralisée (moralized bibles)

- Dedication Page (colophon), with Blanche of Castile and King Louis IX of France, Saint Louis Bible (Moralized Bible or Bible moralisée)

- Humanizing Mary: the Virgin of Jeanne d’Evreux

- Ivory casket with scenes from medieval romances

- Muhammad ibn al-Zain, Basin (Baptistère de Saint Louis)

- What are some of the key characteristics of Gothic architecture?

- What architectural elements enabled Gothic churches to admit more light?

- What new book format appeared in the Gothic period?

- How did depictions of the Virgin Mary and other sacred figures change in the Gothic period?

- pointed arch

- lancet window

- rib vault

- colonette

- elevation

- arcade

- triforium

- flying buttress

- archivolt

- lintel

- jamb figure

- Kings Gallery

- rose window

- tracery

- Rayonnant

- Mamluks

Key Questions

Key Terms

Like the Romanesque, the Gothic was an international style that quickly spread beyond France, engendering new forms, such as the fan vault, in England. Gothic art also produced powerful new devotional images that emphasized emotional aspects of the motherhood of the Virgin Mary and the suffering of her son Jesus.

Beverley Minster, East Riding of Yorkshire, England, begun after 1188, largely complete by 1400

- England

- Gothic architecture explained

- Salisbury Cathedral

- Lincoln Cathedral

- The Chapter House of York Minster

- Gloucester Cathedral

- Four styles of English medieval architecture at Ely Cathedral

- The Wilton Diptych

- Central Europe

- Synagoga and Ecclesia, Strasbourg Cathedral

- Death of the Virgin, South portal, Strasbourg Cathedral

- Hiding the divine in a medieval Madonna: Shrine of the Virgin

- Röttgen Pietà

- Altneushul, Prague

- How did Gothic architecture change over time, in different regions, and in different cultural contexts?

- What were some of the strengths and challenges presented by different building materials in medieval architecture?

- What is an “Opening Virgin” and how might medieval users have engaged with and understood such an object?

- How did Gothic artworks like the Röttgen Pietà encourage emotional engagement with its subject?

- quatrefoil

- crocket

- choir screen

- presbytery

- chapter house

- engaged colonnette

- blind arcade

- blind arch

- cloister

- Early English Gothic

- Decorated Gothic

- Perpendicular Gothic

- fan vault

- Throne of Mercy

- diptych

- Pietà

Key Questions

Key Terms

Jewish, Christian, and Muslim communities coexisted on the Iberian Peninsula (today Spain and Portugal) for centuries. Architecture and manuscripts illustrate cross-cultural influences as well as unique cultural and religious forms and functions.

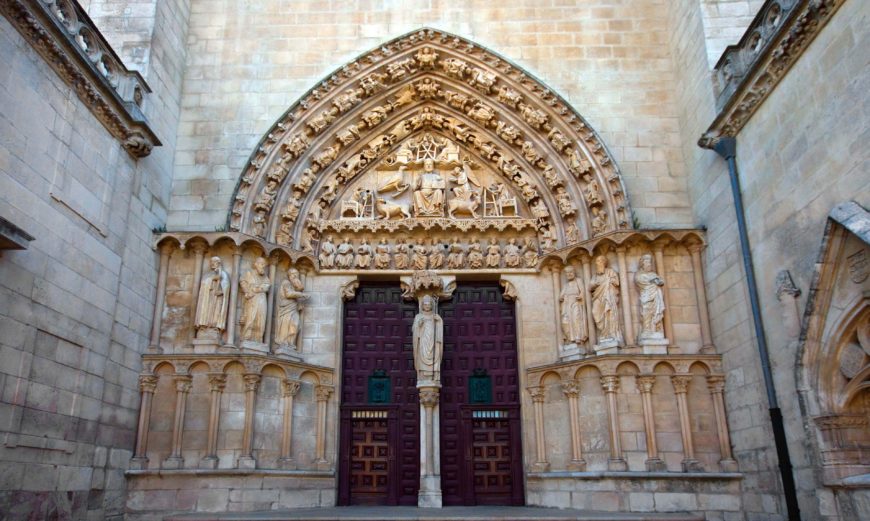

Puerta del Sarmental, 13th century, Burgos Cathedral, Burgos, Spain (photo: Coleccionista de Instantes Fotografia, CC BY-SA 2.0)

- Architecture

- Spanish Gothic cathedrals, an introduction

- Medieval synagogues in Toledo, Spain

- The Alhambra

- Manuscripts

- Joshua ibn Gaon, a decorated Hebrew Bible (MS. Kennicott 2)

- The Prato Haggadah

- The Golden Haggadah

- Book of Morals of Philosophers

- Elisha ben Abraham Cresques and the Farhi Bible

- The Catalan Atlas

- Images of African Kingship, Real and Imagined

- Bifolium from the Pink Qur’an

- In what ways were medieval synagogues, churches, and mosques similar and different on the Iberian Peninsula?

- What are some of the ways that Jewish, Christian, and Islamic manuscripts were similar and different in the middle ages?

- What is a Haggadah and how is it used?

- What is Maghribi script and how is it different from other Islamic scripts?

- choir

- stucco

- volutes

- roundels

- low-relief

- Torah

- Torah niche

- Hebrew Bible

- Haggadah

- Passover

- bifolium

- Maghreb

- calligraphy

- Maghribi script

- diacritical mark

Key Questions

Key Terms

The Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire never fully recovered from the devastating sack of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade in 1204, but the empire’s final years nevertheless witnessed a flurry of rebuilding and artistic production. An increased interest in naturalism and new artistic forms were emblematic of Late Byzantine and late medieval Italian art on the eve of the Italian Renaissance.

Deësis mosaic, c. 1261, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

- Late Byzantine art

- Late Byzantine naturalism: Hagia Sophia’s Deësis mosaic

- Picturing salvation — Chora’s brilliant Byzantine mosaics and frescoes

- Byzantine miniature mosaics

- The vita icon in the medieval era

- Late Gothic Italy

- The Crucifixion, c. 1200 (from Christus triumphans to Christus patiens)

- Inventing the image of Saint Francis

- Giotto, Arena (Scrovegni) Chapel (part 1 of 4)

- Giotto, Arena (Scrovegni) Chapel (part 3 of 4)

- Cimabue, Virgin and Child Enthroned, and Prophets (Santa Trinita Maestà)

- Siena in the Late Gothic, an introduction

- Duccio, Maestà

- Simone Martini, Maestà

- What are some of the new media and pictorial formats that emerged in Late Byzantium and late medieval Italy and how did they spread?

- Who were some of the patrons of late medieval art and how did their patronage impact artistic production?

- What is naturalism and where can it be observed in Late Byzantine and late medieval Italian art?

- What are some of the different ways that human (and divine) bodies were depicted in late medieval art?

- lunette

- stylized

- Christus triumphans

- Christus patiens

- Franciscans

- Mendicant orders

- apron scenes

- trompe-l'œil

- usury

- lamentation

- foreshortening

- volume

- mass

- illusionism

- naturalism

- fresco

Open All

Open All Collapse All

Collapse All