When we think about a portrait, we think about a person. A man or woman, boy or girl. Maybe on occasion a favored pet, but always a living being. The portrait serves as a record of his or her appearance, characteristics, and interests.

Does a portrait have to be of a person, though? People often ascribe human characteristics to inanimate objects. A car that is having trouble starting might be “stubborn,” or a powerful storm might be “angry.” What if the attributes shown in a landscape were supposed to be ascribed to the person who owned that land?

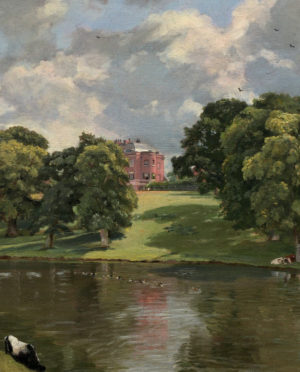

John Constable, Wivenhoe Park, Essex, 1816, oil on canvas, 56.1 x 101.2 cm (National Gallery of Art)

With Wivenhoe Park, Essex, landscape painter John Constable depicted an English country estate in order to make a broader statement about its owner and his relationship with nature in the early nineteenth century.

Wivenhoe Park

Major-General Francis Slater Reboe owned Wivenhoe Park, a quiet countryside estate located approximately seventy miles northeast of London. Rebow was friends with corn merchant Golding Constable, whose son John insisted on pursuing the career of an artist rather than take up his father’s business. The wealthy officer was one of John Constable’s first patrons.

The 200-acre estate at Wivenhoe was the pride of Major-General Rebow’s father-in-law, Colonel Isaac Martin Rebow (interestingly, the Major-General took his wife’s last name after marriage), who purchased the land in the 1730s and commissioned the construction of Wivenhoe House in 1759, and then massive alterations in the 1770s to the surrounding parkland, designed by the landscape architect Richard Woods.

Nicolas Poussin, Landscape with Saint John on Patmos, 1640, oil on canvas, 100.3 x 136.4 cm (The Art Institute of Chicago, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Wivenhoe Park’s grounds were redesigned along the lines of the picturesque, an aesthetic concept which combined elements of the philosophy of the awe-inspiring Sublime and the serene Beautiful—categories of landscape painting in the eighteenth century. An example of the picturesque is Nicolas Poussin’s Landscape with St. John (above), which combines rocky hills and architectural ruins with lush greenery and a peaceful summer’s day.

Arch and bridge (detail), John Constable, Wivenhoe Park, Essex, 1816, oil on canvas, 56.1 x 101.2 cm (National Gallery of Art)

In order to evoke a sense of the picturesque the architect Woods introduced an arch and bridge specifically designed to look old, multiple curving roads lined with trees, and two new lakes for fishing and boating. Rebow’s estate was a prime example of the picturesque in England, and a source of pride for the entire family.

Country home (detail), John Constable, Wivenhoe Park, Essex, 1816, oil on canvas, 56.1 x 101.2 cm (National Gallery of Art)

The gorgeous estate of Wivenhoe Park is evident in Constable’s painting. Filled with rolling hills populated by people and livestock, lit by soft sunlight streaming through low-hanging clouds, and highlighted by a large lake in the foreground and a country home peeking from behind a stand of trees in the background, the landscape of Wivenhoe Park entices viewers with a vision of rural beauty, simplicity, and harmony.

Constable’s connection to nature

Today John Constable is regarded as one of the two great British landscape artists of the nineteenth century, alongside his contemporary J.M.W. Turner. During his lifetime, however, Constable was afforded little respect. He almost exclusively painted landscapes—avoiding the far more popular genres of history painting and portraiture. Most of his artistic output is comprised of images of the rural countryside of England’s Suffolk and Essex counties, where Wivenhoe Park was located. Whereas most artists would sketch scenes in nature before returning to the studio to paint, beginning in 1814 Constable began to bring his canvases outside and paint directly from nature, adding a sense of veracity and immediacy to his paintings and inspiring future artists like those that would form the Barbizon School (French artists who painted landscapes in a forest near Paris, beginning in the 1830s) as well as the later Impressionists (beginning in the 1860s).

John Constable, Wivenhoe Park, Essex, 1816, oil on canvas, 56.1 x 101.2 cm (National Gallery of Art)

Constable was deeply invested in the physical experience of nature. His paintings possess a strong sense of the particular, and demonstrate a keen artist’s eye turned to the environment. The artist famously studied weather reports and spent countless hours sketching clouds, which he rendered with precise meteorological detail in Wivenhoe Park, Essex. Similarly, the play of light and shadow across the right foreground, and the glimmers of light reflected off the pond in the middle of the composition, enhance the sense of a real, observed landscape. Constable believed that an artist could encourage positive and negative emotions in the viewer through the depiction of nature—particularly through the play of light and dark on the landscape and skyscape.

Light and shadow on the water, John Constable, Wivenhoe Park, Essex, 1816, oil on canvas, 56.1 x 101.2 cm (National Gallery of Art)

The present past

The emotions Constable intended to stir up in his viewers were, much like in his later View on the Stour near Dedham (below), those of a nostalgia for the past, and a desire to recapture the English connection to nature that was disappearing during the early decades of the Industrial Revolution (among other things, the shift from producing many objects by hand to mass-produced, factory-made objects using machinery and steam power).

John Constable, View on the Stour near Dedham, 1822, oil on canvas, 51 x 74 inches (The Huntington Library)

Wivenhoe Park, Essex depicts an idyllic England that still physically existed in some locations, but was barely holding on, ideologically speaking. Much like Turner’s The Fighting Temeraire, Wivenhoe Park, Essex celebrates its subject while mourning the end of the era in which it was created. In this sense, the painting functions as a portrait: of eighteenth-century England; of the English countryside; and of the estate’s owner, Major-General Rebow, and the values he attempted to uphold. Considering the fact that much of the picturesque estate of Wivenhoe Park was designed by an architect, the foregrounded presence of the manmade lake also speaks to Rebow’s dominion over the lands he owned.

Mary Rebow (detail), John Constable, Wivenhoe Park, Essex, 1816, oil on canvas, 56.1 x 101.2 cm (National Gallery of Art)

There is one member of the Rebow family included in the composition: Mary Rebow, the 11-year-old daughter of Major-General Rebow, who can be seen on the left side of the canvas driving the donkey cart. Her red scarf, one of the girl’s favorite accessories, is a brief flash of color in a composition otherwise dominated by greens, blues, and browns. Constable, then in his 40th year, seems to have doted on the little girl, perhaps hoping to have a child like her one day with the woman he was then courting, longtime friend Maria Bicknell. Constable’s biographer wrote that Constable’s “fondness for children exceeded, indeed, that of any man I ever knew.” [1] In a letter to Maria dated August 21, 1816, Constable describes his visit to Wivenhoe Park and notes that Major-General Rebow had in fact commissioned two paintings, one of the estate and one of a small building on the estate grounds, both of which were to include references to Mary Rebow: “…the heroine of all these scenes.” [2] The commissions were essentially early marriage gifts to Constable, as the Rebows were well aware that he was saving money to pay for his wedding to Maria, whose grandfather had threatened to disinherit her if she insisted on marrying the financially unstable artist. The two were married on October 2, 1816, less than a month after Constable completed Wivenhoe Park, Essex.

With impending fatherhood on his mind, Constable was aware of the stakes for Major-General Rebow and his daughter. Rebow wanted to secure his legacy and ensure future security for his daughter, yet in this transitional period of history he had no idea what young Mary Rebow’s future would look like, only that her life could not resemble his. Asking Constable to include her in his painting was one way for the Major-General to ensure that Mary was always present in the bucolic landscape she grew up in, regardless of what might come of that landscape in the future. Furthermore, with the inclusion of such small details like the young girl’s scarf, the canvas rewards those viewers who actually knew the family and the estate, and could recognize those references, creating a deeper meaning for the Rebow family and their intimates.

Seam where the artist added additional canvas, visible in white shirt (detail), John Constable, Wivenhoe Park, Essex, 1816, oil on canvas, 56.1 x 101.2 cm (National Gallery of Art)

Wivenhoe Park, Essex is a record of a particular location at a particular moment in time, but also a nostalgic image of the English past, a past that never quite existed. Humans tend to remember the past as far more positive or negative than it may have actually been and Wivenhoe Park, Essex is no exception. The artist rearranged the landscape to create a more harmonious image. For example, the lake and house would not have been visible in the same view in real life. Additionally, at some point during his painting process Constable extended the canvas on both sides to include additional details, such as a hunting lodge on the far right. The seams created where the new pieces of canvas were stitched onto the existing fabric are visible running through the figure of the young boy wearing a white shirt in the boat on the right side of the painting, and on the left through the neck of the black cow in the left foreground.

Prelude to six-footers

Less than two years after completing Wivenhoe Park, Essex, Constable embarked on the process of painting a series of monumental landscape paintings of the Stour River Valley, known as his “six-footers,” a name which referred to the width of the canvases. At 40 years of age when he married Maria Bicknell in 1816, Constable was still seeking the honor of election to the Royal Academy—the surest indicator of professional success for an artist working in England. Wivenhoe Park, Essex serves as a precursor to those massive canvases, allowing the artist to practice organizing a series of complex landscape details, vignettes of daily life, and a visceral depiction of elements, like sun and wind, into one coherent composition.

The “six-footers” vaulted Constable to greater popular acclaim, and eventually he was elected to the Royal Academy in 1829. Wivenhoe Park, Essex remained in possesion of the Rebow family until 1906, and Wivenhoe Park itself until 1902. Perhaps ironicly, considering Major-General Rebow’s apprehension of the forthcoming industrial age and the nostalgia radiating from Constable’s canvas, Wivenhoe Park is now owned by the University of Essex, and the stately Wivenhoe House featured in the center of the painting is now a four-star luxury hotel, used to train university students studying for a career in hospitality.