Mortuary vs. memorial totem poles: Poles had different functions.

Read Now >Chapter

Northern Northwest Coast Art

Interior of Yáay Hít (Whale House) of the Tlingit Ghaaanaxhteidí clan, Klukwan, Alaska, c. 1895. The photo shows the at.óow (Tlingit clan property) of the Ghaaanaxhteidí clan, including the Séew Xh’éen (Rain Screen, in the back), Wormwood house post (left), Strong Man house post (right), and tunics, bentwood boxes, and clan hats, photograph by Winter and Pond (Alaska State Libraries)

In Yáay Hít, the Whale House of the Tlingit Ghaaanaxhteidí clan, a man wearing a tunic beaded with a beaver crest stands proudly beside the many clan treasures on display. These treasures—painted tunics, woven hats and baskets, carved and painted house posts, screens, and boxes—proclaim the identity, pride, and history of the Ghaanaxhteidí clan. The magnificent house post on the left, for example, deeply carved by the renowned Tlingit carver Khaajisdu.áxhch, one of the great sculptors in world history, depicts at its top a figure wearing a woodworm headdress. This figure recalls a clan ancestor who fed a woodworm until it was found and killed, creating a division in the clan which led to a split with the Ghaanaxhteidí traveling northward to found the village of Klukwan. To the right of the house post is the great Séew Xh’éen (Rain Screen), a masterful painting carved in relief by Shkeedlikháa, one of the most gifted painters who ever lived. Bordering the screen are beings who represent “the back splash of raindrops,” according to Tlingit leader and historian William Paul, while the main figure contains many eye-shapes which represent the raindrops. [1] Intricate carvings and paintings cover all of the household items: mountain goat horn spoons for sipping soups, elaborate bentwood boxes for storage of food and precious items, and sacred objects that are brought out during the great potlatch.

In this house, where members of Yáay Hít live with their spouses and children, everyone wakes up early, well before daylight, to work on their many tasks: fishing and hunting, weaving and repairing tools, cooking, and carving and painting. At night, the Elders tell stories around the fire, illuminating through oral literature all of the figures and crests depicted in the arts they see throughout their lives. These are aspects of the traditional life of Northwest Coast Native people. Many aspects of the richly artistic and literary life are retained to this day.

Map of Northwest Coast cultures (underlying map © Google)

The Northwest Coast refers to a narrow geographical area of North America that skirts the Pacific Ocean, running from the northern end of what is currently known as Southeast Alaska, through British Columbia, and south to the Columbia River in Oregon. Tlingit scholar Andrew Hope III aptly coined this region the “Raven Creator Bioregion,” given the shared oral tradition of the Raven told throughout the Northwest Coast. [2] The region is characterized by rich ocean and river habitats that have long oriented Indigenous people to fishing and whaling, and temperate rainforests that provide cedar, spruce, and other wood for many arts.

Scholars typically discuss three areas of the Northwest Coast: Northern, Central, and Southern. Each of these areas is home to diverse Indigenous nations with different languages, kinship patterns, and histories. Nevertheless, there are several commonalities, including the prevalence of carved and woven arts to assert identity and record histories, as well as participation in major winter ceremonies, often called “potlatches.” The potlatch, which comes from the Chinook word “patshatl” (to give), plays an important role in honoring ancestors, establishing leaders and land ownership, passing on oral histories, and re-distributing wealth. The potlatch was banned in Canada and condemned in Alaska from the late nineteenth century to the middle of the twentieth, although many communities quietly continued their “doings.” Today, these important ceremonies are hosted proudly across much of the Northwest Coast, as well as the commissioning of masks, poles, beadwork and other art forms that are often dedicated and gifted at a potlatch.

Northern Northwest Coast

This chapter focuses on the northern Northwest Coast, which includes the Tlingit (Lingít), Haida (Xaadas), and Tsimshian (Ts’msyen) nations. Future chapters will highlight the art of Indigenous nations from the central and southern Northwest Coast as Smarthistory adds more material to illustrate the rich practices of these regions.

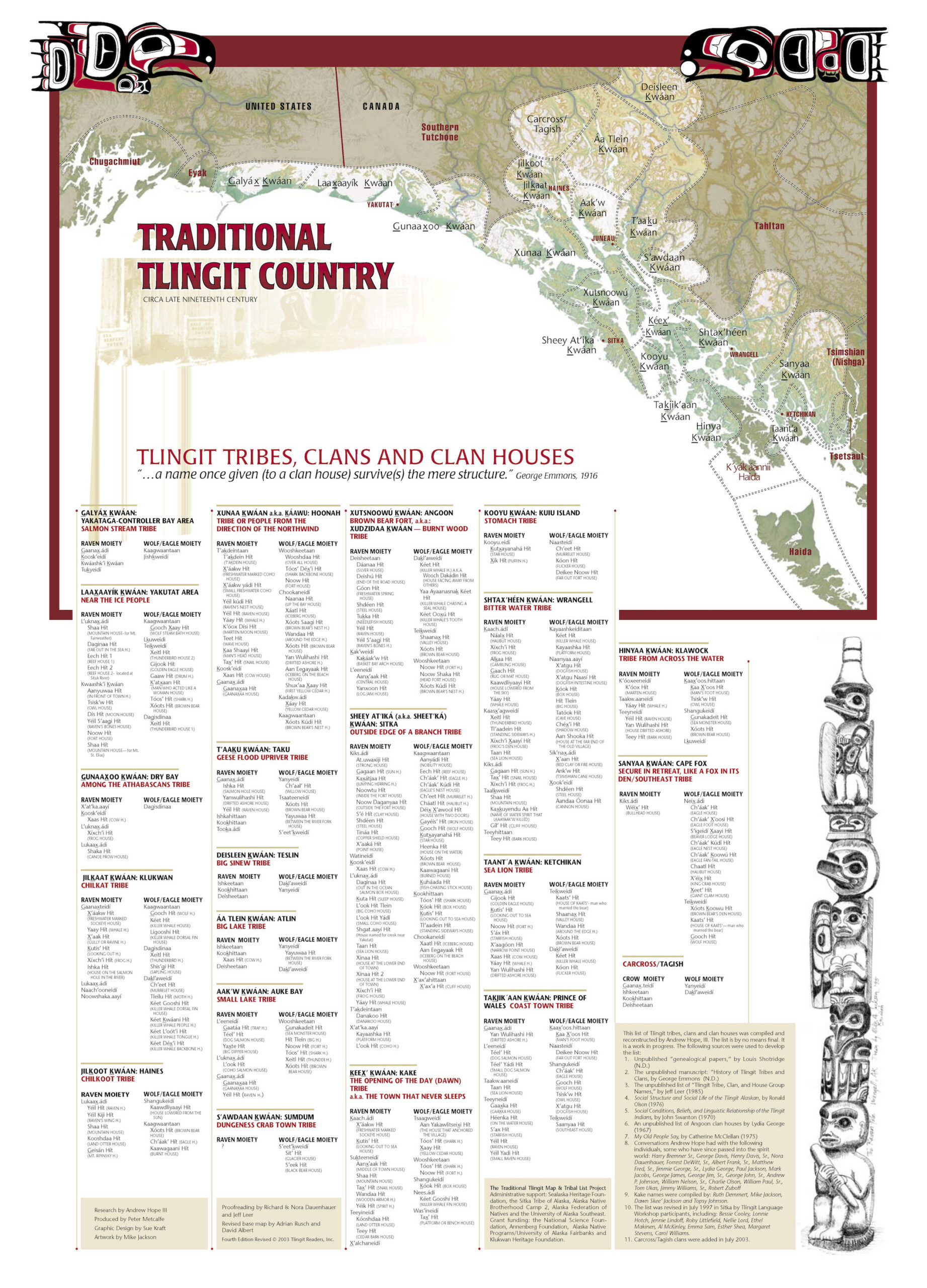

A map with Tlingit tribes, clans, and clan houses, created by Andrew Hope III. Fourth edition revised © 2003 Tlingit Readers, Inc.

The Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian on the northern Northwest Coast all follow matrilineal and exogamous social organization, meaning that children inherit their clan identity from their mother and marry someone from a different clan or lineage. For the Tlingit and Haida, clans are divided into one of two moieties (“halves” in French), Raven and Wolf/Eagle. Tsimshian clans are divided into four phratries, Killerwhale (or Fireweed among the Gitksan), Wolf, Raven, and Eagle. Clans offer “balance” to each other across moiety and phratry, marrying, hosting, and burying their “opposites” (members of a clan from outside their moiety or phratry) to ensure health and harmony in their communities.

The importance of clan identity on the northern Northwest Coast is expressed in art forms that center on crests (symbols owned by and used to identify clans). Many crests depict animals or other beings that ancestors of the clan encountered in the distant past and earned the right (sometimes through their death) to claim as identifying symbols for clan descendants. In addition to the physical objects that display crests, clans own the stories, names, songs, dances, and other intangible property associated with the crest.

Monumental Poles

A portion of Saxman Totem Park, Saxman, Alaska, 2021, that includes multiple monumental poles and a Beaver clan house at the back that was designed by Nathan Jackson (Tlingit) in the early 1990s (photo: Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank, 2021). A number of carvers created poles during work for the Civilian Conservation Corps, and Charles and William Brown oversaw them. Nathan Jackson also headed the construction of a number of the modern poles. The Seward Shame pole was carved by Stephen Jackson in 2017.

The most famous crest objects on the northern Northwest Coast are the monumental carvings commonly known as “totem poles.” This term is misleading, because “totem” is an English word that derives from an Anishinaabe word from the Great Lakes region, “dodem,” which references animals and other beings from which clans trace their lineal descent.

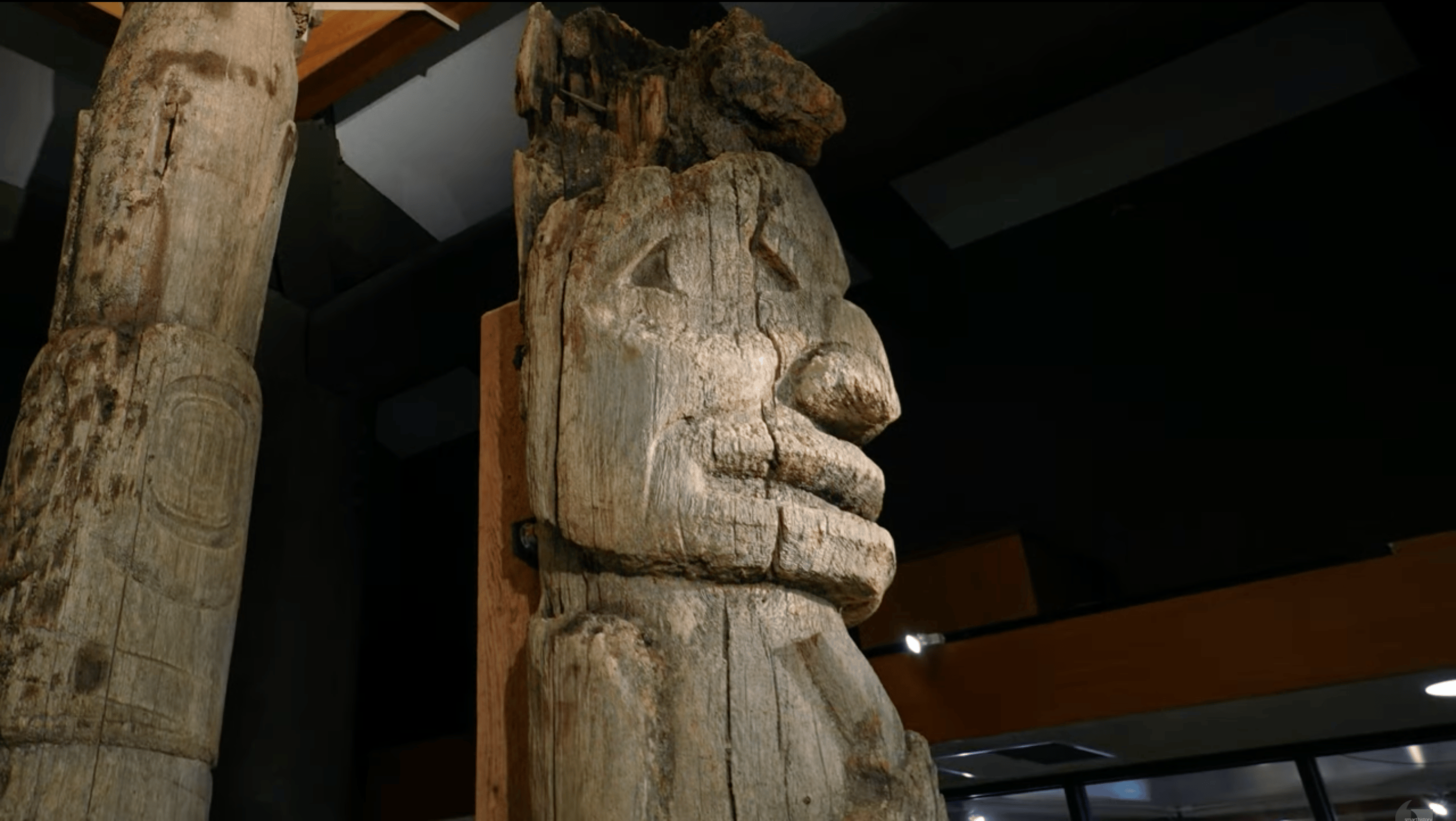

Detail of the lower portion of a Haida clan crest totem Pole, showing a crest of a beaver and baby beaver, 19th century, from Old Kasaan, Alaska (Totem Heritage Center, Ketchikan, Alaska; photo: Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank)

“Crest pole” is probably a better English translation for a pole on the northern Northwest Coast that depicts the animals or beings encountered by clan ancestors and used as identifying symbols, but this meaning also differs from Indigenous names for the poles. In Lingít yoo xhʼatángi, the Tlingit language, poles are “kootéeyaa” (large object carved with a chisel or adze); in Xaad kíl, the Haida language, they are “gyáaʼaang” (man standing up); and in Smʼalgyax, the Tsimshian language, they are “ptsʼaan” (he/she raises his/her history up).

The Haida village of Skidegate in 1878, showing monumental poles, clan houses, and canoes on the beach, photograph by George M. Dawson

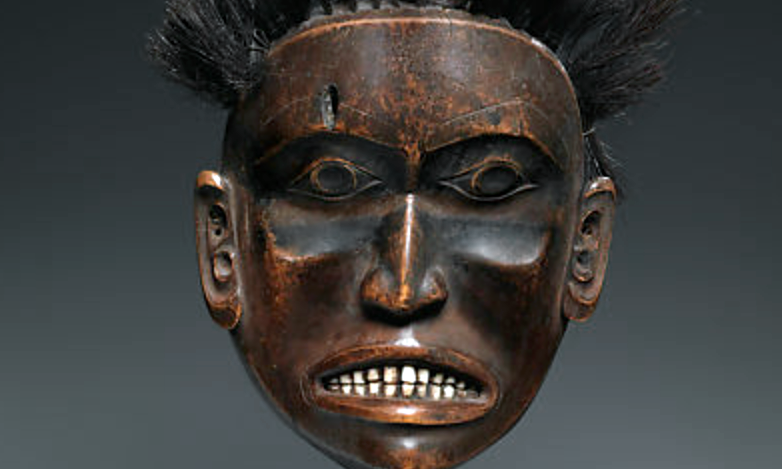

Contrary to popular conception, monumental poles were never worshipped. Poles serve many other functions: mortuary and memorial poles honor the dead, heraldic poles recall stories of clan history or the origins of world phenomena, house frontal and interior posts identify the crests of the house’s resident clan, and ridicule poles shame another clan or person for an unresolved offense. Most poles depict at least one crest of the clan that owns them, while other figures allude to clan histories and stories from oral literature. Tlingit scholar Nora Marks Dauenhauer notes that these figures do not “tell a story” but “refer to stories already known, in much the same way a Christian cross does not ʼtellʼ the Christmas or Easter ʼstory,ʼ but alludes to an entire spiritual tradition.” [3] The rich stories elicited by poles are recounted at potlatches and other events, and always credited to the clan that owns them.

The following videos are case studies of different types of monumental poles from the northern Northwest Coast.

Watch videos about monumental poles

Proud Raven totem pole at Saxman Totem Park: A pole that relates to Indigenous sovereignty.

Read Now >/3 Completed

Northern Northwest Coast Design

Albert Edward Edenshaw (Haida), ts’uu ging.uula guudang (bentwood box), showing the “two-eyes-in-one” motif, c. 1850, cedar wood, paint, and metal, Canada: British Columbia, Haida Gwaii, 70.5 cm x 103.5 cm x 61 cm (Museum of Anthropology, University of British Columbia; photo: Kyla Bailey)

Two-dimensional art of the northern Northwest Coast is most distinctly characterized by what Tlingit anthropologist Louis Shotridge characterized as the “eye motif.” In Tlingit it is called “a waakh” (its eye). According to Tlingit tradition, as told by Louis Shotridge, the form originated among the Tsimshian peoples. A young Tsimshian woman had a dream that she went into the undersea home of Sáanáxhéit, the South Wind, and reported back to her people all the things she saw, most distinctly the many eyes which she felt were looking back at her. The people recreated what the girl described to them, and thus one of the world’s great art traditions was born.

The beauty and complexity of the two-dimensional design system of the northern Northwest Coast is showcased in many arts, including bentwood boxes made of a single cedar plank that is notched, steamed, and bent into shape before being sewn shut on the final side. Boxes had many uses and were numerous, giving artists a large domain to explore two-dimensional design on the boxesʼ sides. In fact, noted anthropologist and art historian Wilson Duff considered a “box” (more precisely a feast dish) “the final exam” of Northwest Coast art, the highest point of the art’s expression.

Boxes often depict the “Sea Wolf” design (in Tlingit, Ghunakadeit; in Haida, Waasghu), which is characterized by the motif of two eyes within a single eye on the flat design surface of the box, as in the box by Albert Edenshaw above. The story of the Sea Wolf is told across the northern Northwest Coast. The belief is that when someone encounters the Ghunakadeit or Waasghu in the sea that good fortune will come to the person who encounters it. Depicting the being which holds riches such as furs, hides, and the clan’s sacred possessions, the people hope that good fortune will come to the owners of such boxes.

Boxes also carry deeply important mythological and metaphorical meanings for the people. The people liken the Elders to “boxes of knowledge.” There is also the very famous history of the baby Raven who cried for the boxes of the Sun, Moon, Stars, and Daylight. In oratory, Tlingits reference the Khei.á Daakeit, the Box of Daylight, likening the joy they wish for their dear opposites to be like the daylight shining upon them.

Raven rattle, Tsimshian artist, 19th century, cedar, pebbles, polychrome, from Skidegate, British Columbia, Canada, 31 × 10.3 × 10.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

By the twentieth century, many Indigenous names for the complex design system on the northern Northwest Coast were lost and others overwritten by English terms like “ovoid” for the eye motif, and “formline” for the curving, calligraphic line that outlines figures on a two-dimensional surface. These English terms were coined in 1965 by non-Native scholar Bill Holm in his book, Northwest Coast Indian Art: An Analysis of Form. However, today many Indigenous communities on the northern Northwest Coast are utilizing their own Native language names for their designs, such as the Haida word “kunjuu” rather than “U-form,” or the Tlingit word “a waakh” rather than “ovoid.”

The following videos discuss the two-dimensional design system on objects from the northern Northwest Coast.

Watch videos about the northern Northwest Coast Design

/2 Completed

House Screens

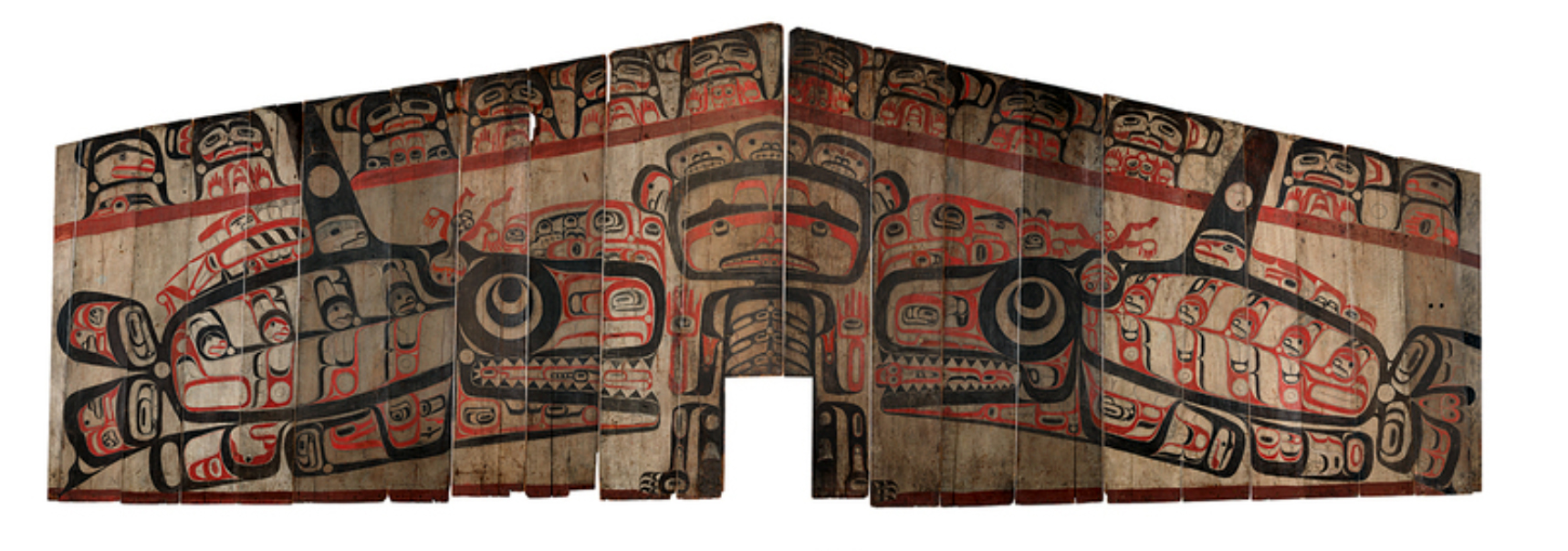

The figure that frames the entry way is the human form of Nagunak, chief of the sea and a crest of the Gisbutwaada clan. He is flanked by two killerwhales, which may represent his sea mammal form in the ocean. Tsimshian house front from Lax Kwʼalaams (Port Simpson), British Columbia, mid-19th century (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution)

The two-dimensional design system is also brilliantly displayed on house screens, both on the front exterior of the house and in the interior, where a screen separates the chiefʼs familyʼs quarters from the rest of the living area. The Haida storyteller Skaay tells of very ancient clan houses having a front house screen that was “painted and sewn,” where the boards of the house screen were sewn together. For example, in the story “One Who Acquired a Wolverine for a Mother,” translated by Robert Bringhurst from ethnographer John Swanton’s transcription, two young brothers leave their home of Kwunwoq and travel to the Nass River. The older brother comes upon the house of Mouse Woman, an important figure in Haida oral tradition. Skaay says,

He’d been riding the falling tide for a time

when a woman, who leaned halfway out of a house up ahead,

said, “Come in!”

The front of the house was painted and sewn.From “One Who Acquired a Wolverine for a Mother” [4]

Skaay’s storytelling doesn’t overlook—and in actuality luxuriates in—such details, as such a “painted and sewn” house front would surely impress visitors with the sense that the host possesses wealth, character, and knowledge of their own history. Since the story is set in Tsimshian country, one imagines a house front similar to the Tsimshian screen pictured here, possibly with mouse designs to signify the owner of the house.

Detail of Nagunak, Tsimshian house front from Lax Kwʼalaams (Port Simpson), British Columbia, mid-19th century (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution)

House fronts and house screens usually depict at least one major crest of the house group. In the lush, monumental Tsimshian screen from Lax Kwʼalaams, for example, the figure that frames the entry way is the human form of the sea chief Nagunak, crest of the Gisbutwada clan.

Detail of a killerwhale, Tsimshian house front from Lax Kwʼalaams (Port Simpson), British Columbia, mid-19th century (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution)

Screens are often rendered in a “classical” style, reflective of the established precepts of the design, which nevertheless innovate because of the skill and talent of the artist. The house front from Lax Kwʼalaams epitomizes this monumentality and grace in its fluid interplay between figuration and lineation, with bold strokes and finely tapered lines delineating the two killerwhales and the sea chief, Nagunak.

Silver Jim Jacobs (Tlingit), Yéilnaawú, Kichshaak, in front of his painting of the Gijook Xh’éen, Yakutat, Alaska, c. 1905

At other times, the style may be slightly more idiosyncratic, such as the delightful Gijook Xh’éen of the Teikhweidí, painted by the well-known early 20th-century Tlingit master artist and silversmith, Silver Jim Jacobs, Yéilnaawú, Kichxhaak. Silver Jim’s touch is bold yet elegant, with the Gijook practically flying out of the screen, offering good fortune to the clan members who treated it with respect.

Weaving

This fine basket shows Nellie Aragonʼs use of the skip stitch pattern (visible as zig zags running vertically up the basket) and multi-colored fibers, including the shiny brown stems of maidenhair fern (visible in the capital “I” shapes known as the “tattoo pattern” in Tlingit basketry). Spruce root basket by Nellie (née Williams) Aragon, Shakéiwés (Tlingit, Kooskʼeidí clan), 1932 (Image courtesy of the Sitka Tribe of Alaska)

In another story told among the Haida, Tsimshian, and Tlingit, a group of siblings were lowered by a basket from the land of the Sun, by their father who was the Sun himself. Some consider this basket to be the first spruce root basket of its kind.

Baskets served many practical purposes, from a holder of foods and other objects, to a pot for boiling water, made out of water-tight baskets in which hot rocks can be placed to boil the water.

Selina Peratrovich, Haida, Kigw, Spruce Root Basket, 1977, twined spruce root basket with lid. Purple “cresting wave” design in false embroidery in center of basket flanked by two bands of “strawberry” design woven into the basket with green dyed spruce root (Ketchikan Museums: Tongass Historical Society Collection, THS 77.7.8.1 A&B)

Weaving is a highly mathematical, perhaps algorithmic art, which is also reflected in the geometric designs that are masterfully woven with false embroidery on the surface of many baskets.

Isabella Edenshaw (Haida), weaver, and Charles Edenshaw (Haida), painter, spruce root hat with killerwhale crest, c. 1885, spruce root and paint (Seattle Art Museum; photo: Joe Mabel, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Spruce root and cedar bark can also be woven into wide-brimmed hats to protect the wearer from the rainy climate of the Northwest Coast and at the same time to display the wearerʼs crests. This hat was woven in the late nineteenth century by Isabella Edenshaw, an extraordinary Haida artist originally from Southeast Alaska. Edenshaw used a skip stitch to create the subtle raised diamond pattern on the surface of the hat; her husband, Charles Edenshaw, then painted a killerwhale crest across the surface, masterfully using the peak of the hat as the dividing line for the two sides of the whale.

Raven’s Tail Weaving

The twining techniques used for weaving tree fibers into baskets are also used for weaving mountain goat wool into prestigious ceremonial robes. According to the late Tlingit weaver Teri Rofkar, spruce root basket weaving is essentially the same as the Raven’s Tail blanket weaving style, which was widespread on the northern Northwest Coast in the eighteenth century.

Teri Rofkar (Tlingit), wearing a Ravenʼs Tail robe that she wove, 2016 (photo: Tom Pich, CC0)

Featuring black geometric designs studded on a white rectangular background, these eye-dazzling robes are known to the Tlingit as “yéil koowú” (ravenʼs tail) after the long black “tails” of weft strings left hanging on the sides of the geometric motifs. To the Haida, they are known as “qwēgal giaʼt” (sky blankets), and figure prominently in Haida oral literature. Ravenʼs Tail weaving was rare for much of the twentieth century, but a resurgence since the 1980s has made this style popular once again on the Northwest Coast.

“Chilkat” weaving

By the early nineteenth century, weavers were pushing beyond the geometric designs of Ravenʼs Tail robes and seeking to translate the curvilinear designs of carved and painted figures into wool. The result is one of the most complex weaving techniques in the world, with twining and braiding techniques that allow for circles and other curved forms to arc across the rectilinear grid of warp and weft.

Naaxein (“Chilkat Robe”) by a Tlingit artist, c. 1850, mountain Goat wool, cedar bark, and dyes, 87 × 175 cm (Hood Museum)

This figurative form of weaving, commonly known in English as “Chilkat weaving” after the Chilkat valley in Alaska where the style proliferated, is called “naaxein” by Tlingit people and “naaxiin” by the Haida. Tsimshian people call robes of this type “Gwishalaayt” (the spirit wraps around you).

Tlingit historians such as the late weaver Jennie Thlunaut, Shaax’sáani Kéek’, and Louis Shotridge, Stuwukhaa, credit the Tsimshian with developing this complex figurative weaving style. Thlunaut stated that a Tsimshian woman named Hayuwáas Tláa was married to a Ghaanaxhteidí man. She owned the S’igeidí K’ideit, the Beaver Apron, which she gave to the Ghaanaxhteidí. Her husband’s clan sisters of the Ghaanaxhteidí unraveled and then reconstructed the apron. This is how the Tlingit learned the art—and given how challenging it is to weave in the Chilkat style, this is truly a feat of ingenuity. The technique spread by marriage to more Tlingit and to the Haida (and later to certain groups among the Kwakwakaʼwakw in the Central Northwest Coast).

Clarissa Rizal, Resilience Robe, 2014, merino wool, 64 x 53 inches (Portland Art Museum)

Today, a handful of weavers continue this complex weaving tradition. Tlingit weaver Lily Hope estimates there are just 200 weavers capable of weaving a circle (one of the most challenging aspects of Chilkat weaving), and 10 who have completed a full-sized robe.

Watch videos about weaving

Dorica Jackson, Diving Whale Chilkat Robe: Robes are worn and enlivened in ceremonial dance, activating the colors, designs, and voluminous fringe.

Read Now >

Clarissa Rizal, Resilience Robe: This prestigious garment follows a traditional design passed down through generations.

Read Now >/2 Completed

Beadwork and buttons

Tlingit guests at a potlatch in Sitka, Alaska, 1904, wearing naaxein robes and beaded regalia, photograph by Elbridge W. Merrill (Alaska State Library)

Beadwork

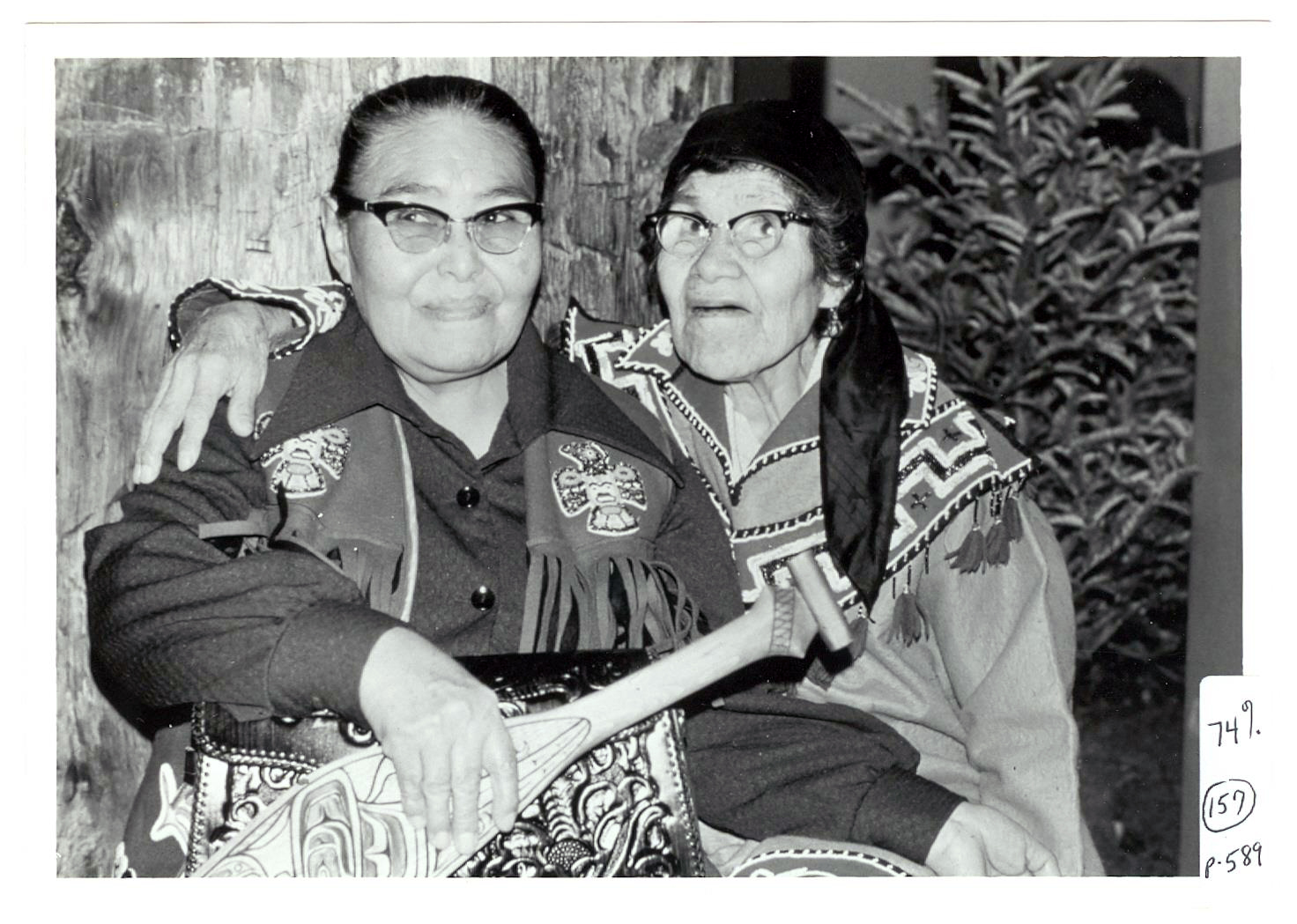

Emma Marks, Seigheighei (Tlingit) and Jennie Thlunaut, Shaaxʼsáani Kéekʼ (Tlingit), April 1974. Emma Marks wears a vest beaded with the raven and sockeye salmon crests of her clan, the Lukaxh.ádi clan of the Raven moiety (the tail of the sockeye salmon can be seen at the bottom left of the image on her vest pocket). Jennie Thlunaut, a master naaxein weaver discussed in this essay, wears a beaded tunic with V-yoke in the Athabascan style that was popular among northern Tlingit communities, like Klukwan where Thlunaut grew up. (Dauenhauer Photograph Collection. PO 004, Box 7, Item 6. William L. Paul Sr. Archives, Sealaska Heritage Institute, Juneau, AK)

Long before the arrival of glass trade beads from Europeans, artists on the northern Northwest Coast used shells obtained from extensive Indigenous trade routes, including abalone from California and dentalium from Vancouver Island. Later, glass beads became popular on the Northwest Coast, particularly among the Tlingit, whose trade with interior Athabascan groups brought floral designs to the coast.

Octopus bag (so-called for the four “tentacles” that hang from the front and back of the bag) with beaded seaweed motifs. Jill Kaasteen Meserve (Tlingit), Octopus bag, or Náaḵw gwéil in Tlingit, 2022, black felt and beads (Sealaska Heritage Institute)

In an interesting twist, however, many Tlingit women chose to bead “geesh” or seaweed designs, transforming the floral traditions of the Interior tundra into beach plants more appropriate to their coastal homelands. Some of the distinguished beadworkers include Esther Littlefield, Aanwooghéex’; Emma Marks, Seigheighei (shown in a photograph earlier); Emma’s daughter Florence Sheakley, Khaakal.aat; and Irene Lampe, Latseenk’i Tláa.

Button blankets

Button blanket by an unrecorded artist, wool and plastic buttons (Denver Art Museum)

Buttons are also used like beads to embellish crest designs in the famous “button blankets” of the Northwest Coast. Button blankets—worn as robes draped over the wearer’s shoulders to display their clan crest across their back—developed in the nineteenth century with the availability of woolen blankets from settler trading posts, particularly the Hudson’s Bay Company. Using the technique of appliqué, artists cut one color of woolen blanket (often red) into the crest design and sew it onto another color (often black); the appliqued crest is then painstakingly outlined in hundreds of buttons.

As artist Dempsey Bob (Tahltan and Tlingit) says of button blankets,

Our people say, when we wear our blankets, we show our face. We show who we are and where we come from.

The pride in the crests and the beauty of the art of button blankets have led many to call them “robes of power.” Today, artists such as Kwakwakaʼwakw artist Marianne Nicholson and Haida fashion designer Dorothy Grant are known for their distinguished work in appliqué and artistry inspired by their button-blanket-making ancestors.

One of the world's great art traditions

Indigenous peoples on the Northwest Coast created one of the world’s great art traditions, renowned for its monumental poles, its complex two-dimensional design system, advanced weaving techniques, and literary wealth. They are proud that their ancestors have continued to make these arts despite the impacts of colonization, which began in the eighteenth century and continue to this day. Still, the art traditions, and the languages and ceremonies which encircle them, persist, spreading the beauty and greatness in their region and across the world. Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian people have found strength in their art forms and continue to uphold “the spirit of the ancestors” in their art today.

Notes:

[1] William Paul, The Alaska Tlingit: Where Did We Come From (Trafford Publishing, 2011), p. 257.

[2] Andrew III Hope, Sacred Form. Andrew Hope III Papers. Unpublished manuscript.

[3] Nora Marks Dauenhauer, “Tlingit At.óow: Traditions and Concepts,” in The Spirit Within: Northwest Coast Native Art form the John H. Hauberg Collection, ed. Steve Brown (Seattle: Seattle Art Museum, 1995), p. 26.

[4] Being in Being: The Collected Works of a Master Haida Mythteller by Skaay of the Qquuna Quiighawaay, translated by Robert Bringhurst (2001).

Key questions to guide your reading

What are the distinctive characteristics of northern Northwest Coast art?

How does the art embody and communicate cultural concepts of clan identity and history?

Jump down to Terms to KnowWhat are the distinctive characteristics of northern Northwest Coast art?

How does the art embody and communicate cultural concepts of clan identity and history?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

Crest

Haida

House screen

Monumental poles

Naaxein or “Chilkat” weaving

Northwest Coast

Potlatch

Raven’s Tail Weaving

Tlingit

Tsimshian

Learn more

Dangel, Helen Dianne. A Celebration of Weavers: Catalogue of Weavers and Baskets of the Dori Borhauer Basket Collection, Sitka, Alaska. Virginia Beach, VA: Donning Company Publishers for Sitka Tribe of Alaska, 2005.

Dauenhauer, Nora Marks and Richard, eds. Haa Tuwunáagu Yís, For Healing Our Spirit: Tlingit Oratory. Seattle: University of Washington Press for Sealaska Heritage Foundation, 1990.

Emmons, George T. “The Whale House of the Chilkat,” Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History, Vol. XIX, Part I. New York: American Museum of Natural History, 1916.

Henrikson, Steve, Lani Hotch, Marie Oldfield, Evelyn Vanderhoop. The Spirit Wraps Around You: Northern Northwest Coast Native Textiles. Juneau, AK: Alaska State Museum, 2021.

Holm, Bill. Northwest Coast Indian Art: An Analysis of Form. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1965.

Jensen, Doreen and Polly Sargent. Robes of Power: Totem Poles on Cloth. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1986.

Jonaitis, Aldona. Art of the Northwest Coast. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2006.

McLennon, Bill and Duffek, Karen. The Transforming Image: Painted Arts of the Northwest Coast, University of Washington Press , 2007.

Paul, William. The Alaska Tlingit: Where Did We Come From? Trafford Publishing, 2011.

Samuel, Cheryl. The Chilkat Dancing Blanket. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1982.

—–. The Raven’s Tail. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1986.

Sealaska Heritage Institute. “Multi-year weaving apprenticeship to culminate in intensive, dancing of the robes at SHI,” Jan. 11, 2023

Skaay of the Qquuna Qiighawaay, translated by Robert Bringhurst. Being in Being: The Collected Works of a Haida Master Haida Mythteller. Douglas and McIntyre, 2001.

Smetzer, Megan A. Painful Beauty: Tlingit Women, Beadwork, and the Art of Resilience. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2021.

Louis Shotridge Digital Archive, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Anthropology.