Use these images to support discussion and research on the Commemorating the U.S. Civil War. Build on the content already included in the essays and videos and refer to the discussion questions related to this theme to frame your inquiry.

This image was part of a famous series of Chicago scenes made by Louis Kurz for the firm Jevne and Almini, just after the Civil War ended. The lithograph shows the Tremont House, a popular hotel and gathering place during the 1850s and 1860s, and where Abraham Lincoln and his political rival Senator Stephen A. Douglas usually stayed when they were in town. Louis Kurz, "Tremont House," 1866, Chicago Illustrated, lithograph, , 8 3/4 x 11 3/4 inches (Chicago History Museum)

This image was part of a famous series of Chicago scenes made by Louis Kurz for the firm Jevne and Almini, just after the Civil War ended. The lithograph shows the Tremont House, a popular hotel and gathering place during the 1850s and 1860s, and where Abraham Lincoln and his political rival Senator Stephen A. Douglas usually stayed when they were in town. Louis Kurz, "Tremont House," 1866, Chicago Illustrated, lithograph, , 8 3/4 x 11 3/4 inches (Chicago History Museum) This image shows the Catskill Mountains region of New York State, a place untouched by battle. In the midst of the beautiful natural landscape, these trees were cut down so that the cowherd at the center could raise cattle and tan the leather for profit. Artist Sanford Robinson Gifford was a U.S. army veteran who had personally witnessed the war. One way of thinking about the sunset and the tree stumps in the painting is that they refer to the sacrifices of Civil War soldiers. Just as the northern men fighting in the war died for the sake of the preservation of the Union, the trees were cut down for a larger cause: the settlement of the United States. Sanford Robinson Gifford, Hunter Mountain, Twilight, 1866, oil on canvas, 30 5/8 x 54 1/8 inches (Terra Foundation for American Art)

This image shows the Catskill Mountains region of New York State, a place untouched by battle. In the midst of the beautiful natural landscape, these trees were cut down so that the cowherd at the center could raise cattle and tan the leather for profit. Artist Sanford Robinson Gifford was a U.S. army veteran who had personally witnessed the war. One way of thinking about the sunset and the tree stumps in the painting is that they refer to the sacrifices of Civil War soldiers. Just as the northern men fighting in the war died for the sake of the preservation of the Union, the trees were cut down for a larger cause: the settlement of the United States. Sanford Robinson Gifford, Hunter Mountain, Twilight, 1866, oil on canvas, 30 5/8 x 54 1/8 inches (Terra Foundation for American Art) This image was part of a famous series of Chicago scenes made by Louis Kurz for the firm Jevne and Almini, just after the Civil War ended. It shows the railroad and part of the wealthy center of the city as veterans returning home from the war would have found it. During the war, the Illinois Central Railroad played a critical role in sending soldiers, arms, and other supplies southward to to the military front. Louis Kurz, "Michigan Avenue from the Lake," Chicago Illustrated, 1866, lithograph based on a drawing, 8 3/4 x 11 3/4 inches (Chicago History Museum)

This image was part of a famous series of Chicago scenes made by Louis Kurz for the firm Jevne and Almini, just after the Civil War ended. It shows the railroad and part of the wealthy center of the city as veterans returning home from the war would have found it. During the war, the Illinois Central Railroad played a critical role in sending soldiers, arms, and other supplies southward to to the military front. Louis Kurz, "Michigan Avenue from the Lake," Chicago Illustrated, 1866, lithograph based on a drawing, 8 3/4 x 11 3/4 inches (Chicago History Museum) Dressed in a simple black dress, eyes directed downward, the young woman in Constant Mayer’s painting mourns the death of her husband. The Civil War produced thousands of widows who were left to raise and support families themselves. Like this woman, they wore special clothing to mark their grief publicly. Constant Mayer, Love's Melancholy, 1866, oil on canvas, 20 1/4 x 14 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago)

Dressed in a simple black dress, eyes directed downward, the young woman in Constant Mayer’s painting mourns the death of her husband. The Civil War produced thousands of widows who were left to raise and support families themselves. Like this woman, they wore special clothing to mark their grief publicly. Constant Mayer, Love's Melancholy, 1866, oil on canvas, 20 1/4 x 14 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago) Based on the story of the funeral of Confederate Captain William Latané (a Virginian who practiced medicine, managed his family’s plantation, and enslaved 200 men, women, and children), the painting honors the white women and the enslaved members of their household whom legend said gave Latané a proper burial when his own family could not do so. The painting embodies the myth of the faithful slave—part of the Lost Cause ideology that insisted that enslaved Black people had loved their enslavers and preferred slavery to freedom. It also portrays the idea of a Confederate soldier as a righteous Christian knight and martyr who nobly sacrifices his life for his homeland—another element of the Lost Cause belief system that cast Confederate men as honorable protectors of the white southern woman. William D. Washington, Burial of Latane, 1864, oil on canvas, 38 x 48 inches (The Johnson Collection)

Based on the story of the funeral of Confederate Captain William Latané (a Virginian who practiced medicine, managed his family’s plantation, and enslaved 200 men, women, and children), the painting honors the white women and the enslaved members of their household whom legend said gave Latané a proper burial when his own family could not do so. The painting embodies the myth of the faithful slave—part of the Lost Cause ideology that insisted that enslaved Black people had loved their enslavers and preferred slavery to freedom. It also portrays the idea of a Confederate soldier as a righteous Christian knight and martyr who nobly sacrifices his life for his homeland—another element of the Lost Cause belief system that cast Confederate men as honorable protectors of the white southern woman. William D. Washington, Burial of Latane, 1864, oil on canvas, 38 x 48 inches (The Johnson Collection) This illustration of a man and a woman out for a carriage ride by the shore accompanied a fictitious story in Harper’s Weekly. The story tells of Captain Harry Ash, who returned from war to resume a courtship with Ms. Edna Ackland and finds that, in his absence, she had learned to drive a carriage. The story reflects how, after the war, white veterans returned to a changed society, and often with changed bodies and abilities due to injury and trauma. And, that white women had become more independent out of necessity. Winslow Homer, Our Watering Places—The Empty Sleeve at Newport, 1865, wood engraving published by Harper's Weekly, August 26, 1865, 9 1/4 x 13 7/8 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago)

This illustration of a man and a woman out for a carriage ride by the shore accompanied a fictitious story in Harper’s Weekly. The story tells of Captain Harry Ash, who returned from war to resume a courtship with Ms. Edna Ackland and finds that, in his absence, she had learned to drive a carriage. The story reflects how, after the war, white veterans returned to a changed society, and often with changed bodies and abilities due to injury and trauma. And, that white women had become more independent out of necessity. Winslow Homer, Our Watering Places—The Empty Sleeve at Newport, 1865, wood engraving published by Harper's Weekly, August 26, 1865, 9 1/4 x 13 7/8 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago) This painting uses symbolism to establish the American family as essential to the restoration of the American union and highlights the role of white women and immigrants as part of that future. During the Civil War, white women entered the workforce and contributed to the war effort. In the difficult years of Reconstruction, their role was less clear, but many felt a patriotic duty to help restore the union. Lily Martin Spencer, The Home of the Red, White, and Blue, c. 1867–68, oil on canvas, 24 x 30 inches (Terra Foundation for American Art)

This painting uses symbolism to establish the American family as essential to the restoration of the American union and highlights the role of white women and immigrants as part of that future. During the Civil War, white women entered the workforce and contributed to the war effort. In the difficult years of Reconstruction, their role was less clear, but many felt a patriotic duty to help restore the union. Lily Martin Spencer, The Home of the Red, White, and Blue, c. 1867–68, oil on canvas, 24 x 30 inches (Terra Foundation for American Art) After the Civil War, both sides took pains to craft their own narratives of the conflict. Former Confederates in particular sought explanations for their defeat and found them in what would come to be known as “The Lost Cause"—a mythology that rewrote the causes of the Civil War to erase the role of slavery and to instead emphasize the heroism of white southern combatants. The painter's melancholy image of a veteran stooped over his rifle standing before the ruin of a modest house, presumably his former home, became a popular expression of a lost past in the years following the war. Henry Mosler, The Lost Cause, 1868, oil on canvas, 91.44 cm x 121.92 cm (The Johnson Collection, photo: Travis Fullerton) © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

After the Civil War, both sides took pains to craft their own narratives of the conflict. Former Confederates in particular sought explanations for their defeat and found them in what would come to be known as “The Lost Cause"—a mythology that rewrote the causes of the Civil War to erase the role of slavery and to instead emphasize the heroism of white southern combatants. The painter's melancholy image of a veteran stooped over his rifle standing before the ruin of a modest house, presumably his former home, became a popular expression of a lost past in the years following the war. Henry Mosler, The Lost Cause, 1868, oil on canvas, 91.44 cm x 121.92 cm (The Johnson Collection, photo: Travis Fullerton) © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts Images that portrayed Confederate generals as honorable and heroic proliferated after the war, creating a set of saints for white southerners to venerate. Everett B. D. Julio’s grand painting, The Last Meeting of Lee and Jackson, portrays two Confederate generals, Robert E. Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, at a poignant moment—riding side-by-side, the evening before Jackson was mortally wounded in a friendly fire incident. Everett B. D. Julio, The Last Meeting of Lee and Jackson, 1869, oil on canvas, 102 x 74 inches (American Civil War Museum)

Images that portrayed Confederate generals as honorable and heroic proliferated after the war, creating a set of saints for white southerners to venerate. Everett B. D. Julio’s grand painting, The Last Meeting of Lee and Jackson, portrays two Confederate generals, Robert E. Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, at a poignant moment—riding side-by-side, the evening before Jackson was mortally wounded in a friendly fire incident. Everett B. D. Julio, The Last Meeting of Lee and Jackson, 1869, oil on canvas, 102 x 74 inches (American Civil War Museum) This Myriopticon is a toy theater containing 22 colored illustrations of the U.S. Civil War. The images are printed on a continuous roll of paper attached to a spindle, which was turned to change the display. The toy is a replica of the real, movie theater-sized shows that were popular in the late 19th century. The stories were to be read aloud as the images were shown. The Myriopticon (Realia): Historical Panorama: The Rebellion, not after 1890, Milton Bradley and Co. toy theater, 14 x 21 x 6 cm (Newberry Library)

This Myriopticon is a toy theater containing 22 colored illustrations of the U.S. Civil War. The images are printed on a continuous roll of paper attached to a spindle, which was turned to change the display. The toy is a replica of the real, movie theater-sized shows that were popular in the late 19th century. The stories were to be read aloud as the images were shown. The Myriopticon (Realia): Historical Panorama: The Rebellion, not after 1890, Milton Bradley and Co. toy theater, 14 x 21 x 6 cm (Newberry Library) The Freedmen’s Bureau, a governmental agency dedicated to aiding formerly enslaved people, opened schools to teach literacy to the formerly enslaved (who had been forbidden to learn to read and write under slavery) and worked to reunite families separated during slavery. In this photograph, a large number of Black children pose in front of white adults before the Beaufort Library on the South Carolina coast. White plantation owners and their families abandoned the town in 1861 after the battle of Port Royal, leaving behind thousands of enslaved people, including an estimated 2,100 children. Hubbard & Mix, Freedmen and teachers in front of the Beaufort Library (detail from stereograph), c. 1862, albumen silver print, 8 x 17 cm (Library of Congress)

The Freedmen’s Bureau, a governmental agency dedicated to aiding formerly enslaved people, opened schools to teach literacy to the formerly enslaved (who had been forbidden to learn to read and write under slavery) and worked to reunite families separated during slavery. In this photograph, a large number of Black children pose in front of white adults before the Beaufort Library on the South Carolina coast. White plantation owners and their families abandoned the town in 1861 after the battle of Port Royal, leaving behind thousands of enslaved people, including an estimated 2,100 children. Hubbard & Mix, Freedmen and teachers in front of the Beaufort Library (detail from stereograph), c. 1862, albumen silver print, 8 x 17 cm (Library of Congress) In 1863 Charlotte Forten, then a 25-year-old Black missionary teacher and poet from Philadelphia, began to teach freed Black children in South Carolina. Charles Milton Bell, Studio portrait of Charlotte L. Forten Grimke, c. 1870–79, carte-de-visite, 9 x 6.5 cm (Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library)

In 1863 Charlotte Forten, then a 25-year-old Black missionary teacher and poet from Philadelphia, began to teach freed Black children in South Carolina. Charles Milton Bell, Studio portrait of Charlotte L. Forten Grimke, c. 1870–79, carte-de-visite, 9 x 6.5 cm (Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library) The decoration of this whiskey jug demonstrates the use of satire and humor to reflect on political events and social conventions. Scholars believe that the snakes refer to the political party known as the Copperheads, who opposed the war and advocated restoration of the Union through a negotiated settlement with the South. Anna Pottery, Snake Jug, c. 1865, stoneware with painted decoration, 31.75 x 21.11 x 22.07 cm (Minneapolis Institute of Art)

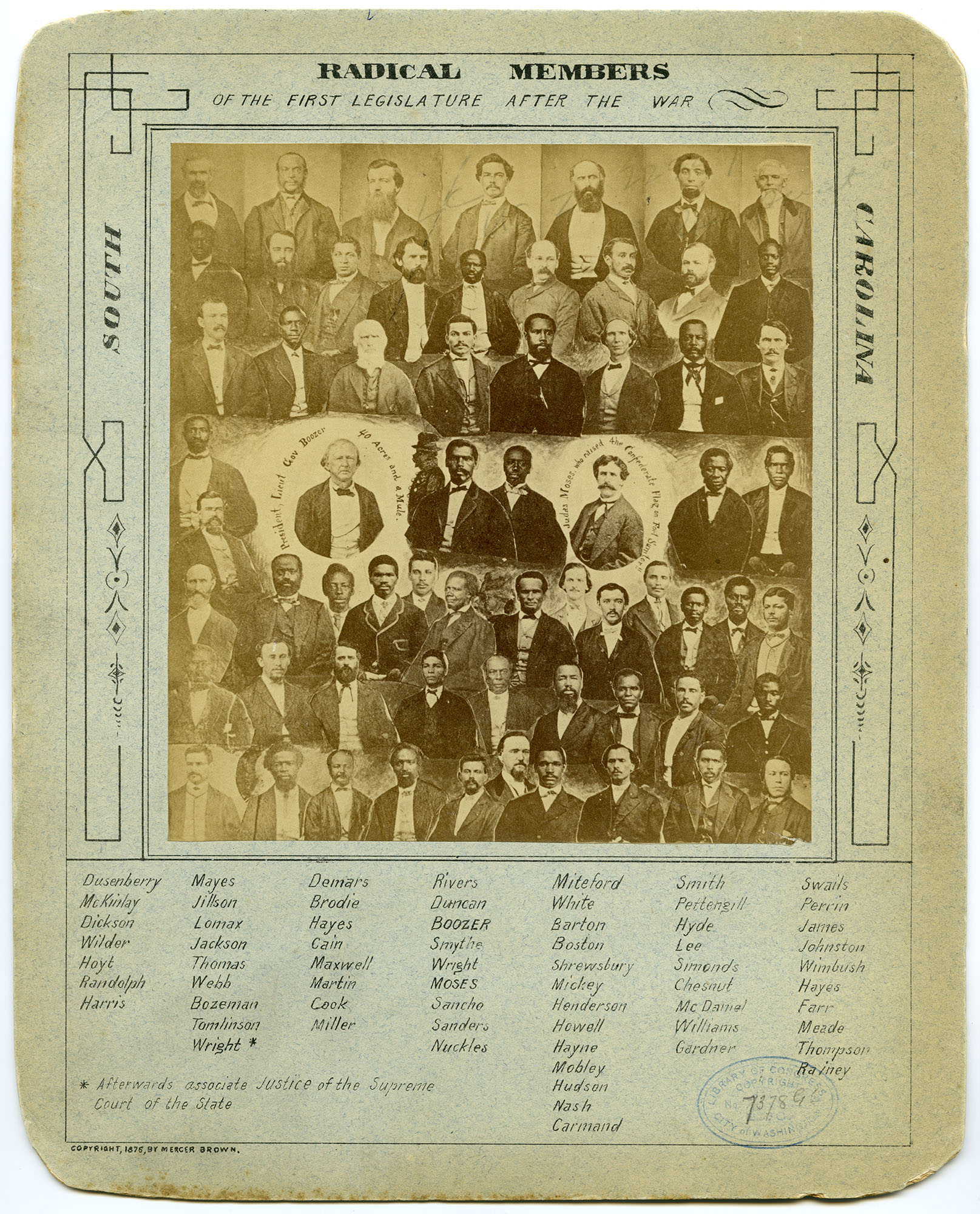

The decoration of this whiskey jug demonstrates the use of satire and humor to reflect on political events and social conventions. Scholars believe that the snakes refer to the political party known as the Copperheads, who opposed the war and advocated restoration of the Union through a negotiated settlement with the South. Anna Pottery, Snake Jug, c. 1865, stoneware with painted decoration, 31.75 x 21.11 x 22.07 cm (Minneapolis Institute of Art) This image, entitled “Radical Members,” is a photomontage of portraits of members of the 1868 South Carolina legislature—the first to be elected after South Carolina was readmitted to the United States following the Civil War. This image (and others like it, showing newly elected Black and white officials), was widely circulated to stoke fears among South Carolina’s white population. Radical members of the first legislature after the war, South Carolina, c. 1876 (Library of Congress)

This image, entitled “Radical Members,” is a photomontage of portraits of members of the 1868 South Carolina legislature—the first to be elected after South Carolina was readmitted to the United States following the Civil War. This image (and others like it, showing newly elected Black and white officials), was widely circulated to stoke fears among South Carolina’s white population. Radical members of the first legislature after the war, South Carolina, c. 1876 (Library of Congress) This political cartoon promotes support for the Republican party by condemning Democrats. Details in the cartoon link Democrats with the conspiracies among white-led organizations to use violence and intimidation to disenfranchise and suppress formerly enslaved people during Reconstruction. Thomas Nast, "The Union As It Was—Worse Than Slavery," Harper’s Weekly, October 24, 1874, wood engraving (Library of Congress)

This political cartoon promotes support for the Republican party by condemning Democrats. Details in the cartoon link Democrats with the conspiracies among white-led organizations to use violence and intimidation to disenfranchise and suppress formerly enslaved people during Reconstruction. Thomas Nast, "The Union As It Was—Worse Than Slavery," Harper’s Weekly, October 24, 1874, wood engraving (Library of Congress) Both white northerners and southerners erected monuments that concentrated on the common white soldier at the expense of other participants in the war. The most common Civil War monument is the citizen soldier monument, an image of a single white volunteer soldier in a relaxed pose, rifle at ease, standing atop a column or pedestal, such as this monument to the soldiers of Roxbury, Massachusetts. Depicting one enlisted soldier pensively leaning against his upturned rifle, Roxbury’s monument was not unique; in fact, there were at least seven casts made of this statue to provide similar monuments for the dead or veterans of other northern towns. Martin Milmore (sculptor) and Ames Manufacturing Company (founder), Roxbury Soldier Monument, Forest Hills Cemetery, Boston, 1867 (photo: Sarah Beetham, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

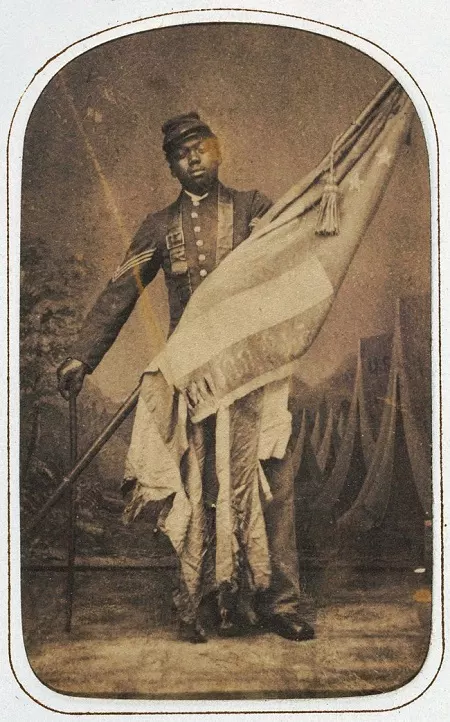

Both white northerners and southerners erected monuments that concentrated on the common white soldier at the expense of other participants in the war. The most common Civil War monument is the citizen soldier monument, an image of a single white volunteer soldier in a relaxed pose, rifle at ease, standing atop a column or pedestal, such as this monument to the soldiers of Roxbury, Massachusetts. Depicting one enlisted soldier pensively leaning against his upturned rifle, Roxbury’s monument was not unique; in fact, there were at least seven casts made of this statue to provide similar monuments for the dead or veterans of other northern towns. Martin Milmore (sculptor) and Ames Manufacturing Company (founder), Roxbury Soldier Monument, Forest Hills Cemetery, Boston, 1867 (photo: Sarah Beetham, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) A rare (and perhaps entirely unique) citizen soldier monument featuring a Black soldier is located in West Point Cemetery, an African American graveyard in Norfolk, Virginia, where dozens of Black soldiers and sailors who served in the Civil War are buried. The model for the soldier was Sergeant William H. Carney, who was born into slavery in Norfolk and who served in the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment. Civil War Union Soldier Monument, West Point Cemetery, completed in 1920

A rare (and perhaps entirely unique) citizen soldier monument featuring a Black soldier is located in West Point Cemetery, an African American graveyard in Norfolk, Virginia, where dozens of Black soldiers and sailors who served in the Civil War are buried. The model for the soldier was Sergeant William H. Carney, who was born into slavery in Norfolk and who served in the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment. Civil War Union Soldier Monument, West Point Cemetery, completed in 1920 William H. Carney, who served as the model for the Civil War Union Soldier Monument at West Point Cemetery (a rare, and perhaps entirely unique, citizen soldier monument featuring a Black soldier), was born into slavery in Norfolk and served in the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment. He later became the first Black soldier to be awarded a Medal of Honor. The monument at West Point Cemetery was erected in 1920. John Ritchie, Sgt William Carney holding the American Flag, c. 1864 , from a carte-de-visite album of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, 1864 (National Museum of African American History and Culture)

William H. Carney, who served as the model for the Civil War Union Soldier Monument at West Point Cemetery (a rare, and perhaps entirely unique, citizen soldier monument featuring a Black soldier), was born into slavery in Norfolk and served in the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment. He later became the first Black soldier to be awarded a Medal of Honor. The monument at West Point Cemetery was erected in 1920. John Ritchie, Sgt William Carney holding the American Flag, c. 1864 , from a carte-de-visite album of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, 1864 (National Museum of African American History and Culture) McCauley was a decorated Civil War veteran. We see his two crossed swords, his hat (a kepi), his leather belt and revolver holster, and his canteen. Two cherished post-war medals from the Grand Army of the Republic and Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States take a place of pride at the top of the painting. These military artifacts function as a kind of portrait of McCauley and we are tricked into thinking that the aging military items shown are real objects and not just painted. George Cope, Civil War Regalia of Major Levi Gheen McCauley, 1887, oil on canvas, 50 x 46 1/2 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago)

McCauley was a decorated Civil War veteran. We see his two crossed swords, his hat (a kepi), his leather belt and revolver holster, and his canteen. Two cherished post-war medals from the Grand Army of the Republic and Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States take a place of pride at the top of the painting. These military artifacts function as a kind of portrait of McCauley and we are tricked into thinking that the aging military items shown are real objects and not just painted. George Cope, Civil War Regalia of Major Levi Gheen McCauley, 1887, oil on canvas, 50 x 46 1/2 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago) John Alexander Logan was a lawyer and politician from Illinois who gave up his position as a United States congressman to join the U.S. Army during the Civil War. The monument portrays Logan when he commanded the Army of the Tennessee during the Battle of the Atlanta in 1864. Along the base of the Logan Monument, there are a series of bronze wreaths along with inscriptions of the names of the battles in which he participated. Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Alexander Phimister Proctor, John Alexander Logan Monument, 1897, bronze figure on a granite base atop a grassy mound, Grant Park, Chicago, 60 x 80 x 200 feet (Chicago Park District)

John Alexander Logan was a lawyer and politician from Illinois who gave up his position as a United States congressman to join the U.S. Army during the Civil War. The monument portrays Logan when he commanded the Army of the Tennessee during the Battle of the Atlanta in 1864. Along the base of the Logan Monument, there are a series of bronze wreaths along with inscriptions of the names of the battles in which he participated. Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Alexander Phimister Proctor, John Alexander Logan Monument, 1897, bronze figure on a granite base atop a grassy mound, Grant Park, Chicago, 60 x 80 x 200 feet (Chicago Park District) This equestrian statue stands atop of a high mound rising above Grant Park’s landscape next to Michigan Avenue in Chicago, Illinois. In his right hand, Logan is holding a flag high in the air. Its pole is topped with a small figure of an eagle, the national bird. This flag symbolizes a sense of patriotism to America and the goal of preserving the Union. Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Alexander Phimister Proctor, John Alexander Logan Monument, 1897, bronze figure on a granite base atop of a grassy mound, Grant Park, Chicago, 60 x 80 x 200 feet (Chicago Park District)

This equestrian statue stands atop of a high mound rising above Grant Park’s landscape next to Michigan Avenue in Chicago, Illinois. In his right hand, Logan is holding a flag high in the air. Its pole is topped with a small figure of an eagle, the national bird. This flag symbolizes a sense of patriotism to America and the goal of preserving the Union. Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Alexander Phimister Proctor, John Alexander Logan Monument, 1897, bronze figure on a granite base atop of a grassy mound, Grant Park, Chicago, 60 x 80 x 200 feet (Chicago Park District) General Sheridan was the commander of the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac in Virginia. This monument shows Sheridan looking over his shoulder, arm outstretched and hat in hand, rallying his troops to regain control of the battleground. John Gutzon Borglum, General Philip Henry Sheridan Monument, 1923, bronze figure on granite base, Lincoln Park, Chicago, 20 x 10 x 10 feet (Chicago Park District)

General Sheridan was the commander of the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac in Virginia. This monument shows Sheridan looking over his shoulder, arm outstretched and hat in hand, rallying his troops to regain control of the battleground. John Gutzon Borglum, General Philip Henry Sheridan Monument, 1923, bronze figure on granite base, Lincoln Park, Chicago, 20 x 10 x 10 feet (Chicago Park District) At the dedication of the monument in 1891, President Henry Harrison made a speech in which he described Grant as “a tower of strength and confidence in the crisis of our Civil War.” Grant entered the army as a U.S. colonel. He quickly worked his way up the ranks, becoming the Commander General of the U.S. Army in 1864. During the next year, he led a grueling, brutal final campaign through Virginia, which culminated in Confederate defeat at Petersburg and Richmond, and the surrender of Lee’s army at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. Louis T. Rebisso, Ulysses S. Grant Memorial, 1891, bronze figure on an arched masonry setting, Lincoln Park (Chicago Park District)

At the dedication of the monument in 1891, President Henry Harrison made a speech in which he described Grant as “a tower of strength and confidence in the crisis of our Civil War.” Grant entered the army as a U.S. colonel. He quickly worked his way up the ranks, becoming the Commander General of the U.S. Army in 1864. During the next year, he led a grueling, brutal final campaign through Virginia, which culminated in Confederate defeat at Petersburg and Richmond, and the surrender of Lee’s army at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. Louis T. Rebisso, Ulysses S. Grant Memorial, 1891, bronze figure on an arched masonry setting, Lincoln Park (Chicago Park District) The monument to Ulysses S. Grant in front of the U.S. Capitol Building, at once grand and intimate, speaks to both the valor and the horror of the Civil war. This massive tripartite memorial features a bronze equestrian statue of Grant on a central pedestal flanked by two sculptural groups of soldiers. Ulysses S. Grant was a two-term president who led the U.S. troops to victory, culminating in the surrender of the Confederacy in 1865. The same year that the memorial was unveiled, the Lincoln Memorial was completed at the far west end of the National Mall. With the great thinking man Lincoln on one end and on the other the great man of action, Grant, the National Mall tells the story that together they succeeded in saving what George Washington had established. Henry Merwin Shrady (sculptor) and William Pearce Casey (architect), Ulysses S. Grant Memorial with the US Capitol Building in the background, Washington, D.C., 1901–22, marble and bronze, 520 x 500 x 120 cm (photo: Martin Falbisoner, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The monument to Ulysses S. Grant in front of the U.S. Capitol Building, at once grand and intimate, speaks to both the valor and the horror of the Civil war. This massive tripartite memorial features a bronze equestrian statue of Grant on a central pedestal flanked by two sculptural groups of soldiers. Ulysses S. Grant was a two-term president who led the U.S. troops to victory, culminating in the surrender of the Confederacy in 1865. The same year that the memorial was unveiled, the Lincoln Memorial was completed at the far west end of the National Mall. With the great thinking man Lincoln on one end and on the other the great man of action, Grant, the National Mall tells the story that together they succeeded in saving what George Washington had established. Henry Merwin Shrady (sculptor) and William Pearce Casey (architect), Ulysses S. Grant Memorial with the US Capitol Building in the background, Washington, D.C., 1901–22, marble and bronze, 520 x 500 x 120 cm (photo: Martin Falbisoner, CC BY-SA 3.0) This print is shows a room in the White House where President Abraham Lincoln is surrounded by his family—wife Mary, and sons (in order of age), Robert (in an officer’s uniform), Willie, and Tad. But Willie died in February, 1862, and Robert Todd did not join the military until 1864. The family gathering shown here, therefore, could never have taken place. Edward Herline, Abraham Lincoln and Family, c. 1862, lithograph, 24 x 29 inches (Chicago History Museum)

This print is shows a room in the White House where President Abraham Lincoln is surrounded by his family—wife Mary, and sons (in order of age), Robert (in an officer’s uniform), Willie, and Tad. But Willie died in February, 1862, and Robert Todd did not join the military until 1864. The family gathering shown here, therefore, could never have taken place. Edward Herline, Abraham Lincoln and Family, c. 1862, lithograph, 24 x 29 inches (Chicago History Museum) In the early spring of 1860, a young, ambitious Chicago sculptor named Leonard Volk invited Abraham Lincoln to visit his studio. Volk wanted to make a portrait bust of Lincoln, a prominent Springfield lawyer and rising star of the brand new Republican Party. Leonard Wells Volk, Life mask and hands of Lincoln, 1886, bronze, 9 x 8 x 5 inches (mask), 6 x 4 x 3 inches (left hand), 6 x 5 x 3 inches (right hand) (Chicago History Museum)

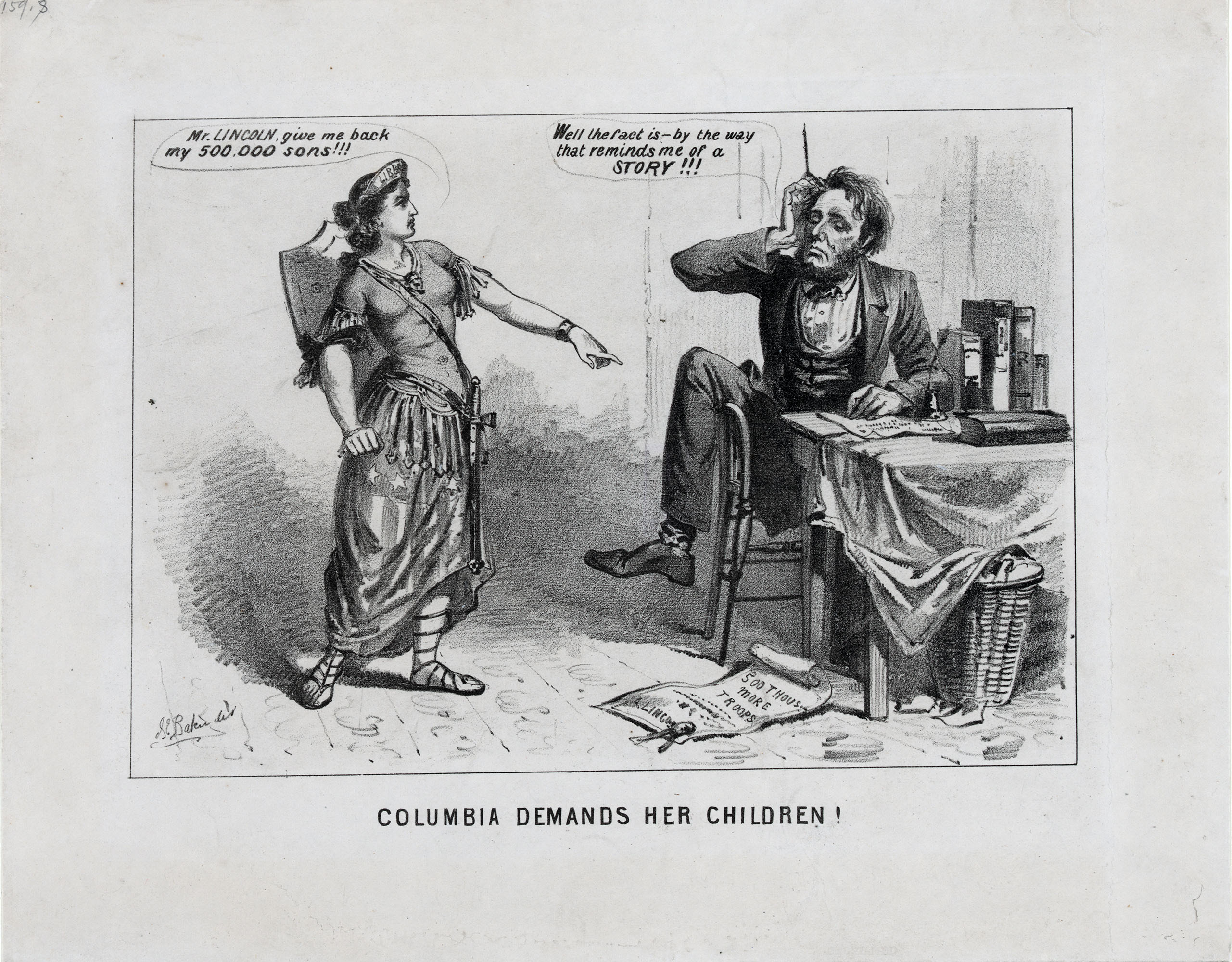

In the early spring of 1860, a young, ambitious Chicago sculptor named Leonard Volk invited Abraham Lincoln to visit his studio. Volk wanted to make a portrait bust of Lincoln, a prominent Springfield lawyer and rising star of the brand new Republican Party. Leonard Wells Volk, Life mask and hands of Lincoln, 1886, bronze, 9 x 8 x 5 inches (mask), 6 x 4 x 3 inches (left hand), 6 x 5 x 3 inches (right hand) (Chicago History Museum) In this political cartoon, the figure of Columbia (an allegorical representation of the United States) wears ancient Roman garb, an American flag skirt, a shield on her back, and a crown inscribed “Liberty” as she accuses Lincoln of wasting the lives of U.S. soldiers. The artist channeled the anger felt by many white northerners that their sacrifices had not translated into victory after three years of fighting, and that Lincoln had mismanaged the war. After Lincoln’s death in 1865, however, such unflattering depictions became extremely rare. Joseph E. Baker, Columbia Demands Her Children! Boston, 1864 (Library of Congress)

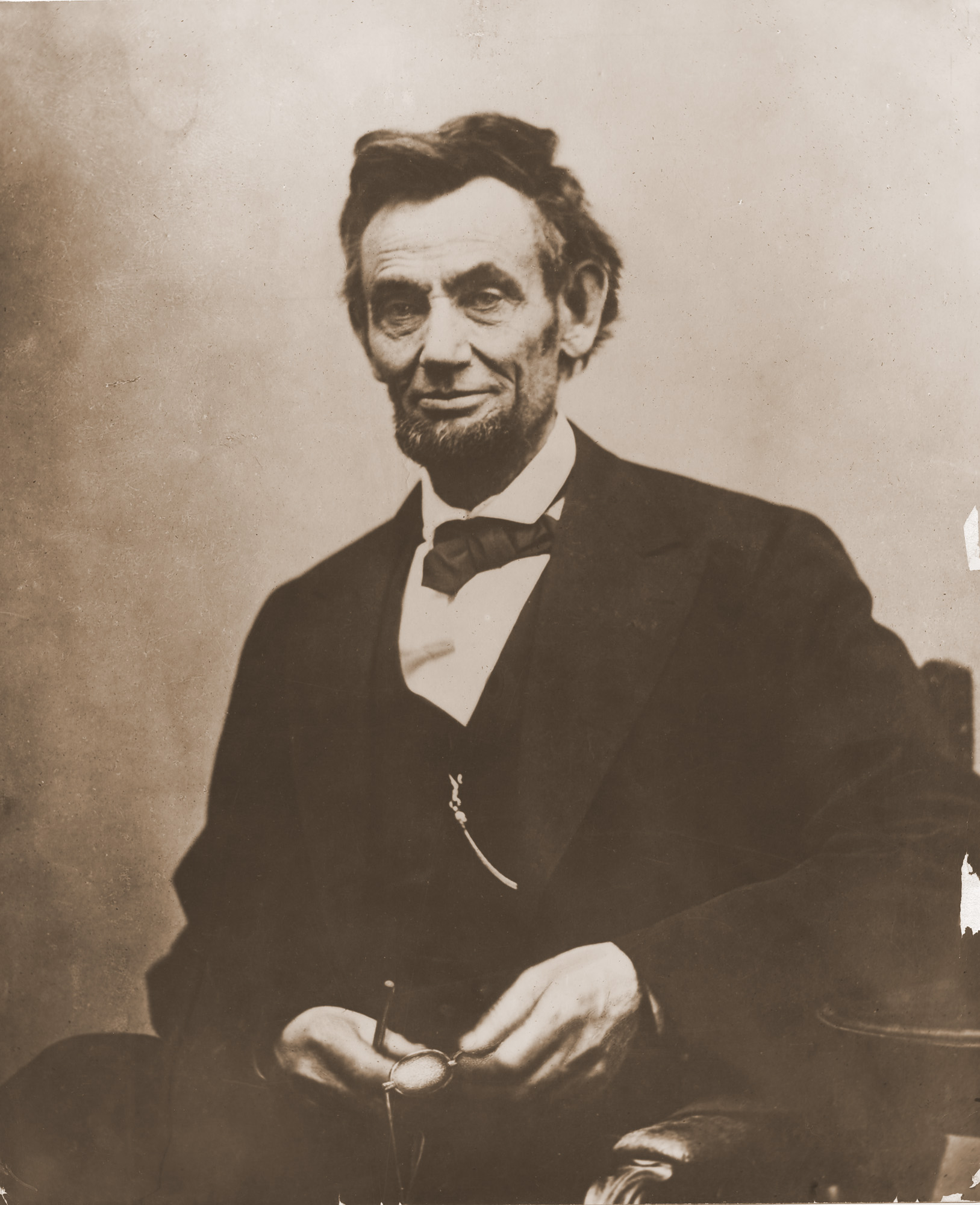

In this political cartoon, the figure of Columbia (an allegorical representation of the United States) wears ancient Roman garb, an American flag skirt, a shield on her back, and a crown inscribed “Liberty” as she accuses Lincoln of wasting the lives of U.S. soldiers. The artist channeled the anger felt by many white northerners that their sacrifices had not translated into victory after three years of fighting, and that Lincoln had mismanaged the war. After Lincoln’s death in 1865, however, such unflattering depictions became extremely rare. Joseph E. Baker, Columbia Demands Her Children! Boston, 1864 (Library of Congress) Alexander Gardner took this photograph the day after the Civil War ended, and only four days before Abraham Lincoln would be assassinated by John Wilkes Booth. Lincoln looks very tired—he had aged a great deal since he took office. Yet he also appears relieved, almost happy. Alexander Gardner, Abraham Lincoln in Washington, D.C., April 10, 1865, 1865, photograph (Chicago History Museum)

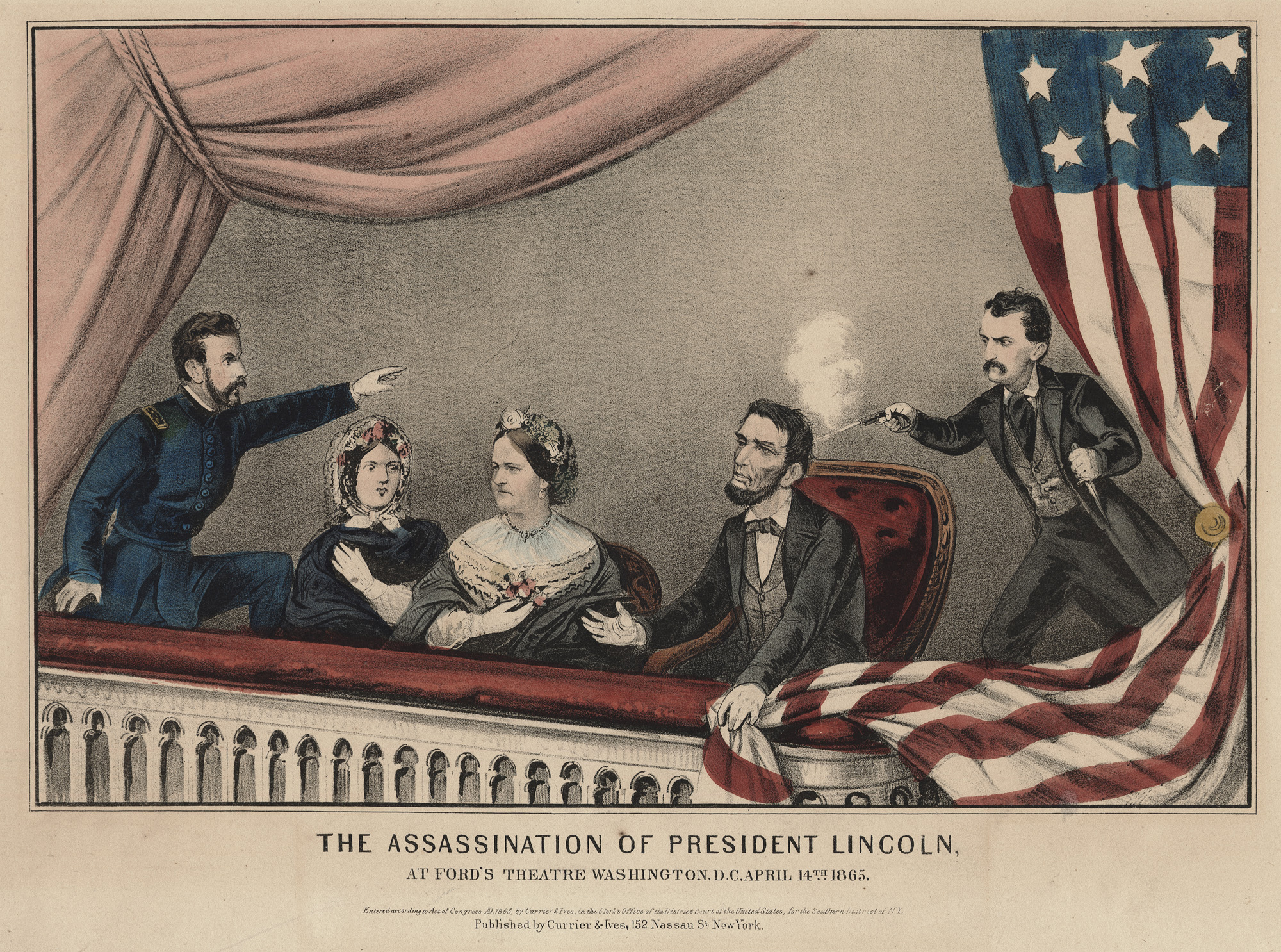

Alexander Gardner took this photograph the day after the Civil War ended, and only four days before Abraham Lincoln would be assassinated by John Wilkes Booth. Lincoln looks very tired—he had aged a great deal since he took office. Yet he also appears relieved, almost happy. Alexander Gardner, Abraham Lincoln in Washington, D.C., April 10, 1865, 1865, photograph (Chicago History Museum) This image depicts John Wilkes Booth shooting Abraham Lincoln at Ford’s Theater, Washington, D.C., on April 14, 1865. The war had only ended two days before. The makers of the print—New Yorkers Nathaniel Currier and James Merritt Ives—produced best-selling lithographs of sports, landscapes, natural wonders, and famous people. Paintings and sculptures were expensive, but lithographs could be made by the thousands, and so were very cheap. Nathaniel Currier and James Merritt Ives, The Assassination of President Lincoln, 1865, lithograph, 14 x 17 inches (Chicago History Museum)

This image depicts John Wilkes Booth shooting Abraham Lincoln at Ford’s Theater, Washington, D.C., on April 14, 1865. The war had only ended two days before. The makers of the print—New Yorkers Nathaniel Currier and James Merritt Ives—produced best-selling lithographs of sports, landscapes, natural wonders, and famous people. Paintings and sculptures were expensive, but lithographs could be made by the thousands, and so were very cheap. Nathaniel Currier and James Merritt Ives, The Assassination of President Lincoln, 1865, lithograph, 14 x 17 inches (Chicago History Museum) On the evening of April 14, 1865, while watching a popular play at Ford’s Theatre, Lincoln was shot in the head by John Wilkes Booth, an actor and Confederate sympathizer. Carried across the street to a small boarding house and placed on a bed too small for his long body, Lincoln never regained consciousness and died early the next morning, just six days after the Civil War ended. He was the first American president to be assassinated, and the nation plunged into deep mourning and great uncertainty. But his sudden death also made him a legendary hero for the country. Alonzo Chappel, The Last Hours of Abraham Lincoln, 1868, oil on canvas, 52 x 98 inches (Chicago History Museum)

On the evening of April 14, 1865, while watching a popular play at Ford’s Theatre, Lincoln was shot in the head by John Wilkes Booth, an actor and Confederate sympathizer. Carried across the street to a small boarding house and placed on a bed too small for his long body, Lincoln never regained consciousness and died early the next morning, just six days after the Civil War ended. He was the first American president to be assassinated, and the nation plunged into deep mourning and great uncertainty. But his sudden death also made him a legendary hero for the country. Alonzo Chappel, The Last Hours of Abraham Lincoln, 1868, oil on canvas, 52 x 98 inches (Chicago History Museum) President Abraham Lincoln's funeral was a huge event that occurred across much of the United States over the course of twelve days. A special train brought the coffin westward from Washington, D.C. back to Lincoln's hometown of Springfield, Illinois. At each stop, mourners turned out to see the funeral train and, in some cities such as Chicago, to view the body itself. Funeral procession outside Cook County Court House, May 1, 1865, 1865, photograph (Chicago History Museum)

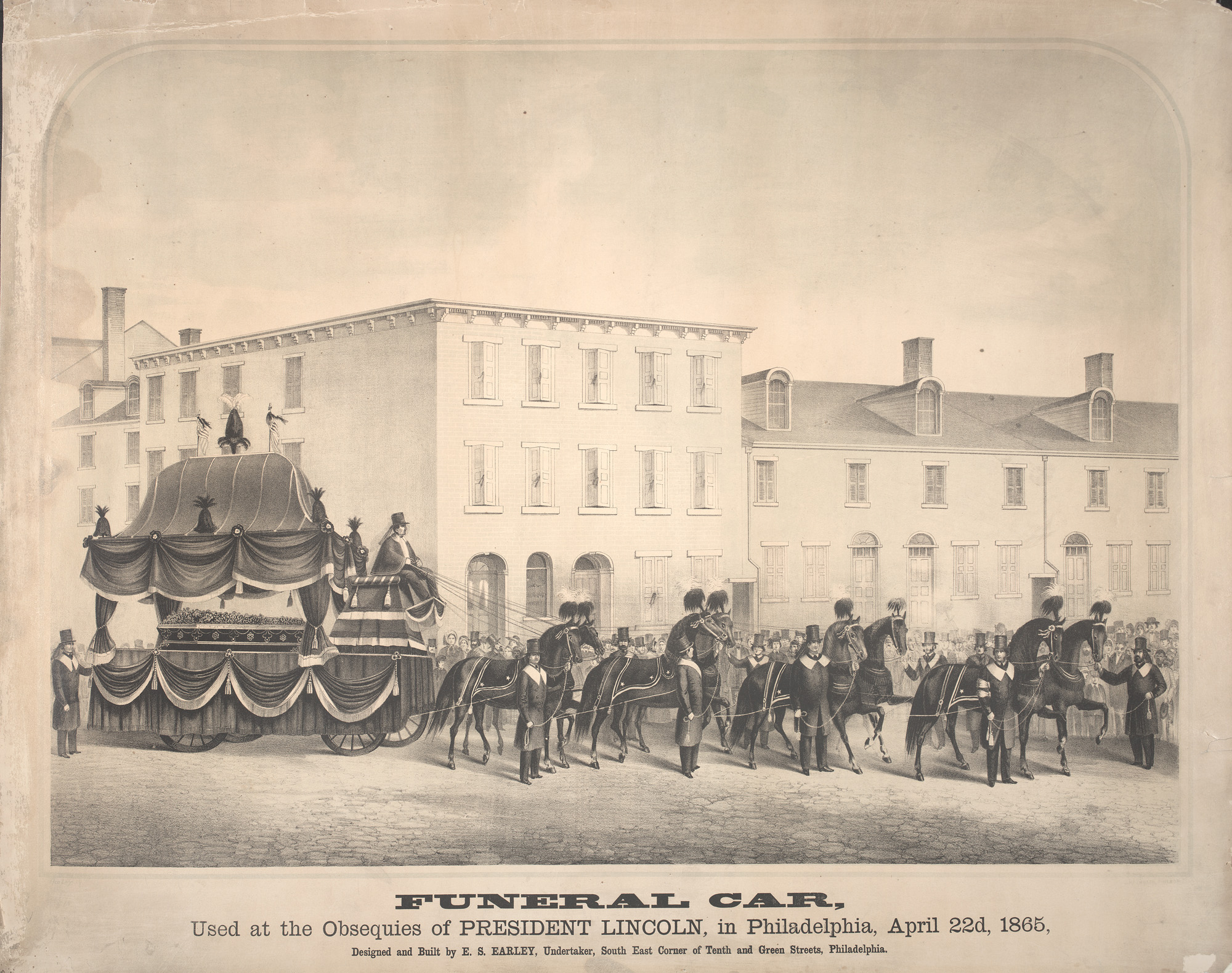

President Abraham Lincoln's funeral was a huge event that occurred across much of the United States over the course of twelve days. A special train brought the coffin westward from Washington, D.C. back to Lincoln's hometown of Springfield, Illinois. At each stop, mourners turned out to see the funeral train and, in some cities such as Chicago, to view the body itself. Funeral procession outside Cook County Court House, May 1, 1865, 1865, photograph (Chicago History Museum) Though Abraham Lincoln’s corpse traveled in a train from Washington to his hometown of Springfield, Illinois, his coffin stopped at towns and cities along the way so that he could be viewed by the people. Local governments spent thousands of dollars draping buildings in black cloth, building complex coverings—called catafalques—for the coffin, and, as we see in this print, preparing funeral carriages to move Lincoln’s body from the train to local funeral ceremonies. Augustus Tholey, Funeral Car, c. 1865, broadside, 23 x 29 inches (Chicago History Museum)

Though Abraham Lincoln’s corpse traveled in a train from Washington to his hometown of Springfield, Illinois, his coffin stopped at towns and cities along the way so that he could be viewed by the people. Local governments spent thousands of dollars draping buildings in black cloth, building complex coverings—called catafalques—for the coffin, and, as we see in this print, preparing funeral carriages to move Lincoln’s body from the train to local funeral ceremonies. Augustus Tholey, Funeral Car, c. 1865, broadside, 23 x 29 inches (Chicago History Museum) In this photograph, President Lincoln’s coffin—in a special covered platform called a catafalque—passes through elaborate arches erected on Park Place in Chicago. The president’s remains were pulled by a carriage with eight black horses. Thirty-six young women, in white dresses and black scarves and headbands, each symbolizing one of the states of the Union, placed wreaths on the coffin and then walked with it on the way to Court House. The funeral in Chicago was the second to last stop of Lincoln’s funeral train, which journeyed for thirteen days from Washington, D.C. Lincoln’s remains lay in state in Chicago for the public to view for the next day and evening, after which his body was taken to its burial site in Springfield, Illinois. H.W. Immke, Lincoln Catafalque, 1865, photograph (Chicago Public Library)

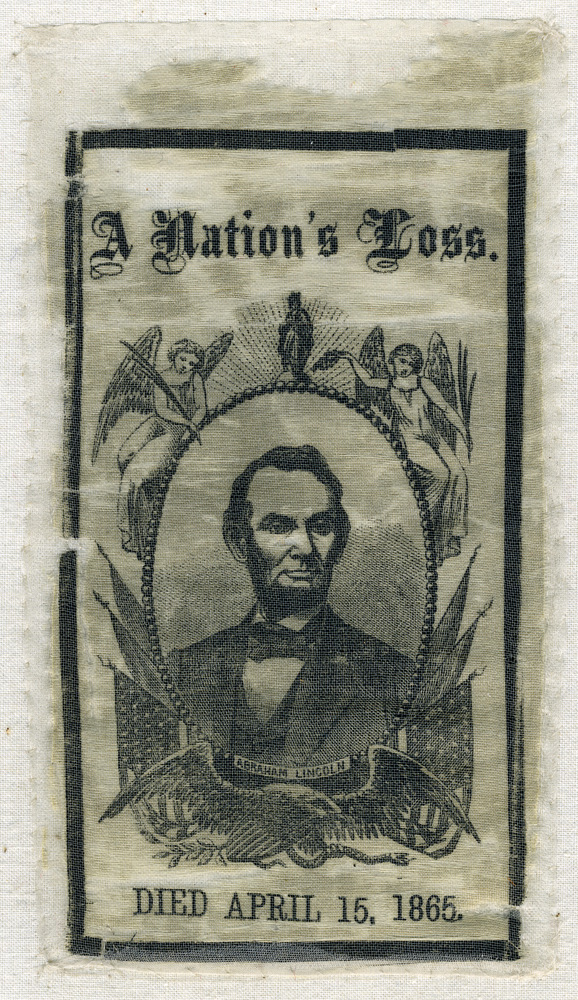

In this photograph, President Lincoln’s coffin—in a special covered platform called a catafalque—passes through elaborate arches erected on Park Place in Chicago. The president’s remains were pulled by a carriage with eight black horses. Thirty-six young women, in white dresses and black scarves and headbands, each symbolizing one of the states of the Union, placed wreaths on the coffin and then walked with it on the way to Court House. The funeral in Chicago was the second to last stop of Lincoln’s funeral train, which journeyed for thirteen days from Washington, D.C. Lincoln’s remains lay in state in Chicago for the public to view for the next day and evening, after which his body was taken to its burial site in Springfield, Illinois. H.W. Immke, Lincoln Catafalque, 1865, photograph (Chicago Public Library) This black-bordered ribbon, made of silk, was worn by Americans after Abraham Lincoln’s assassination. In the 19th century, Americans wore not only black clothing, but also black ribbons and arm bands to show respect and sorrow. A Nation's Loss, 1865, silk ribbon, 5.5 x 3 inches (Chicago Public Library)

This black-bordered ribbon, made of silk, was worn by Americans after Abraham Lincoln’s assassination. In the 19th century, Americans wore not only black clothing, but also black ribbons and arm bands to show respect and sorrow. A Nation's Loss, 1865, silk ribbon, 5.5 x 3 inches (Chicago Public Library) Columbia was a female personification of America invented in the colonial era; her name is drawn from Columbus. Like Uncle Sam, she came to represent the United States in the 19th century. Columbia’s headdress is illuminated as is the president’s name. In the corners of the image, Nast portrayed a grieving soldier (on the left) and sailor (on the right). Thomas Nast, "Columbia Grieving at Lincoln's Bier," Harper's Weekly, April 29, 1865, pp. 264-65 (Chicago Public Library)

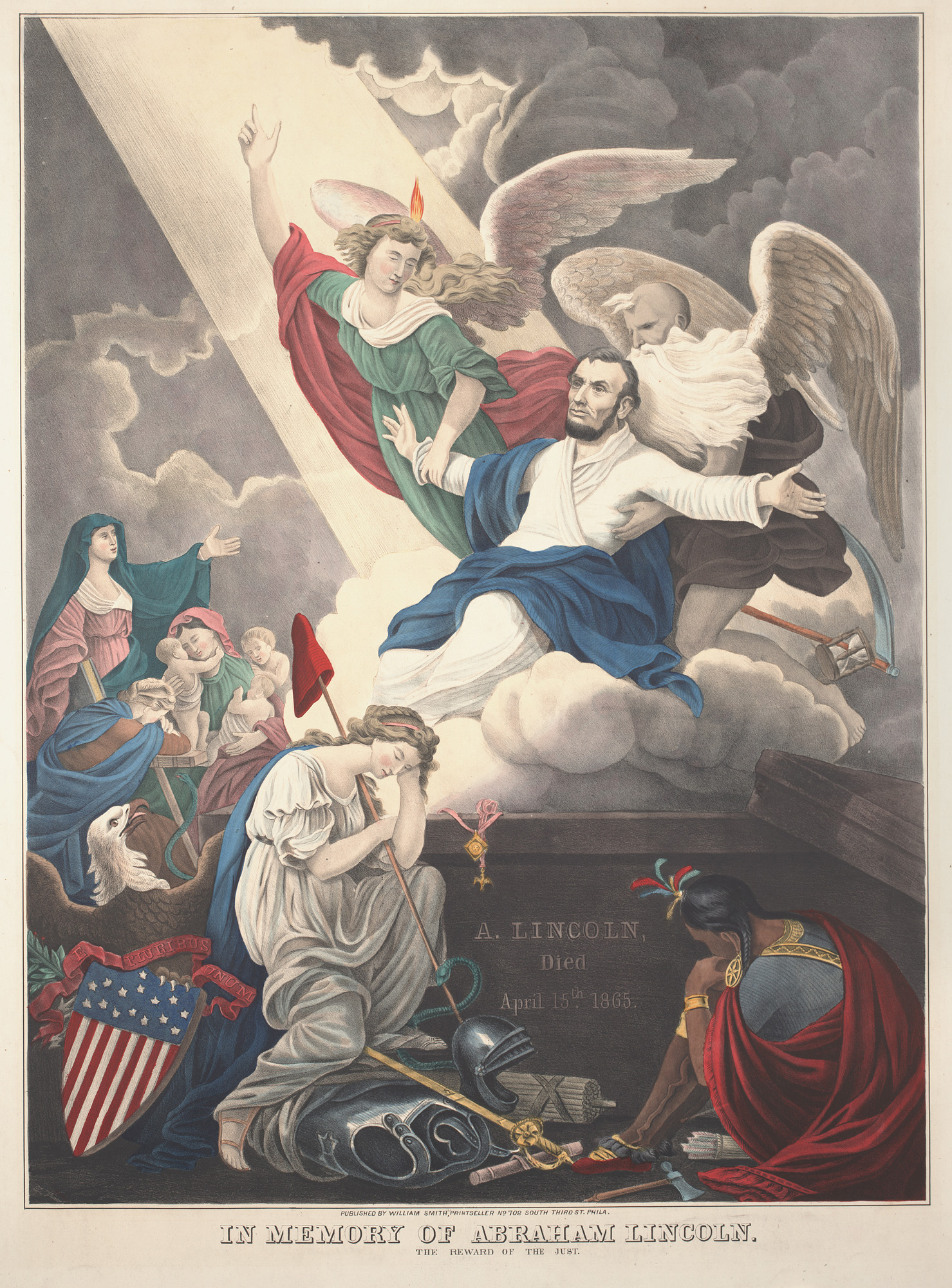

Columbia was a female personification of America invented in the colonial era; her name is drawn from Columbus. Like Uncle Sam, she came to represent the United States in the 19th century. Columbia’s headdress is illuminated as is the president’s name. In the corners of the image, Nast portrayed a grieving soldier (on the left) and sailor (on the right). Thomas Nast, "Columbia Grieving at Lincoln's Bier," Harper's Weekly, April 29, 1865, pp. 264-65 (Chicago Public Library) Abraham Lincoln is shown emerging from his earthly tomb and being carried to heaven by Father Time (the bearded figure just behind Lincoln—notice his scythe and hourglass), while an angel helps. The Civil War era was a time of great religious feeling, and the “reward of the just” refers to Lincoln earning a place in heaven, beyond time, beloved by his country. D. T. Wiest, In Memory of Abraham Lincoln: The Reward of the Just, 1865, 30 x 24 inches (Chicago History Museum)

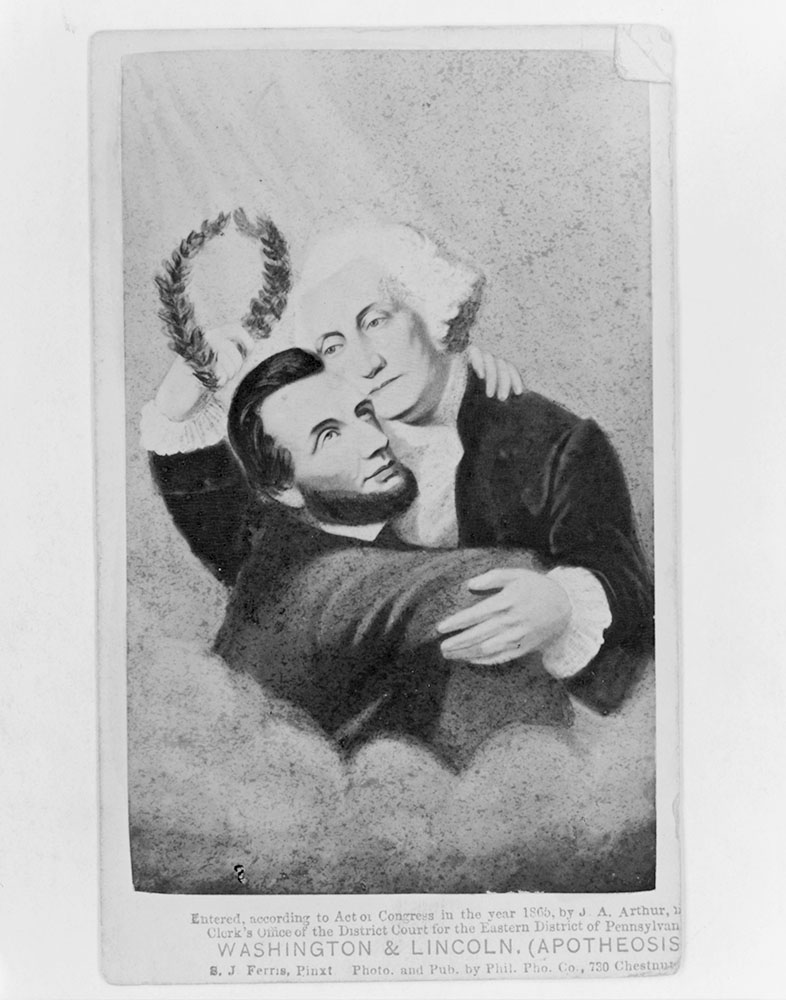

Abraham Lincoln is shown emerging from his earthly tomb and being carried to heaven by Father Time (the bearded figure just behind Lincoln—notice his scythe and hourglass), while an angel helps. The Civil War era was a time of great religious feeling, and the “reward of the just” refers to Lincoln earning a place in heaven, beyond time, beloved by his country. D. T. Wiest, In Memory of Abraham Lincoln: The Reward of the Just, 1865, 30 x 24 inches (Chicago History Museum) While he was in office, Abraham Lincoln’s image was closely tied to public opinion of the war effort and the actions of his administration. But after his assassination—the first of a president in U.S. history—Lincoln was portrayed in art as a Christ-like figure who had died in pursuit of the Union’s salvation. S. J. Ferris, Washington & Lincoln (Apotheosis), albumen print on carte-de-visite, 1865 (Library of Congress)

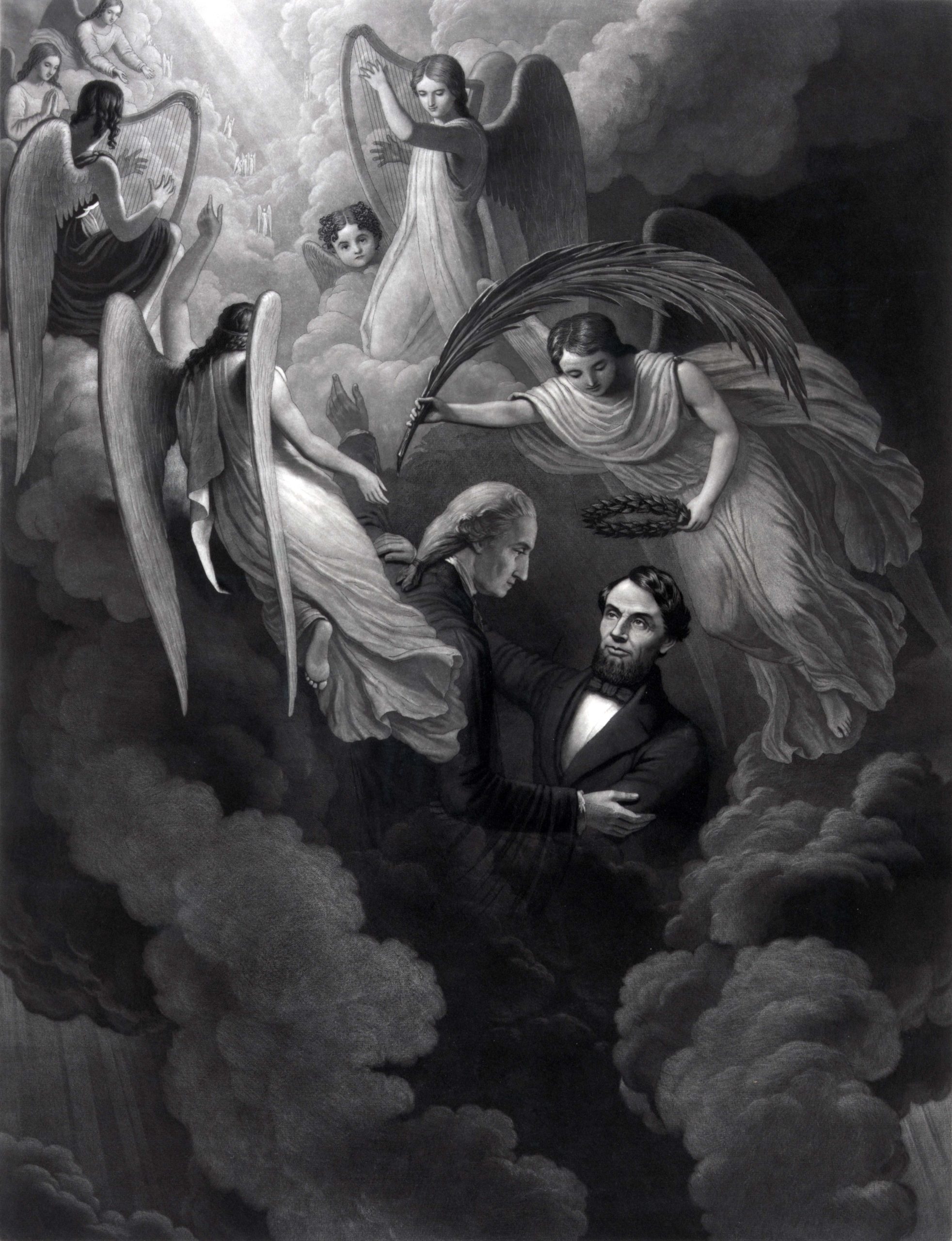

While he was in office, Abraham Lincoln’s image was closely tied to public opinion of the war effort and the actions of his administration. But after his assassination—the first of a president in U.S. history—Lincoln was portrayed in art as a Christ-like figure who had died in pursuit of the Union’s salvation. S. J. Ferris, Washington & Lincoln (Apotheosis), albumen print on carte-de-visite, 1865 (Library of Congress) Abraham Lincoln was the first U.S. president to be assassinated, and Americans reacted to his death with shock. Soon after, an explosion of images of Lincoln appeared that mourned his death and depicted him as a martyr. Several illustrators imagined what happened to Lincoln’s spirit after he died, showing his apotheosis (transformation into a divine figure). John Sartain, Abraham Lincoln, the Martyr, Victorious, 1866 (Library of Congress)

Abraham Lincoln was the first U.S. president to be assassinated, and Americans reacted to his death with shock. Soon after, an explosion of images of Lincoln appeared that mourned his death and depicted him as a martyr. Several illustrators imagined what happened to Lincoln’s spirit after he died, showing his apotheosis (transformation into a divine figure). John Sartain, Abraham Lincoln, the Martyr, Victorious, 1866 (Library of Congress) This painting shows Abraham Lincoln’s visit to the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, on April 4, 1865. The day before, the city had fallen into U.S. Army hands, signaling the end of the Civil War. In painting the crowd, the artist has included more white people than actually attended Lincoln’s ride. Though some white people loyal to the United States came out to see the president, the vast majority of those who gathered around his carriage were Black. Notice, as well, that although men are tossing their hats in the air to celebrate Lincoln’s arrival, the scene depicts the burned-out buildings of heavily damaged Richmond, a somber reminder of war’s destructive powers. Dennis Malone Carter, Lincoln’s Drive Through Richmond, 1866, oil on canvas, 45 x 68 inches (Chicago History Museum)

This painting shows Abraham Lincoln’s visit to the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, on April 4, 1865. The day before, the city had fallen into U.S. Army hands, signaling the end of the Civil War. In painting the crowd, the artist has included more white people than actually attended Lincoln’s ride. Though some white people loyal to the United States came out to see the president, the vast majority of those who gathered around his carriage were Black. Notice, as well, that although men are tossing their hats in the air to celebrate Lincoln’s arrival, the scene depicts the burned-out buildings of heavily damaged Richmond, a somber reminder of war’s destructive powers. Dennis Malone Carter, Lincoln’s Drive Through Richmond, 1866, oil on canvas, 45 x 68 inches (Chicago History Museum) This painting captures a solemn meeting on March 27, 1865, between Abraham Lincoln, and, left to right, his generals William T. Sherman and Ulysses S. Grant, and Admiral David Porter, aboard the ship River Queen at City Point, Virginia. The River Queen was General Grant’s headquarters during the last months of the war, and this scene occurred as the war neared its end. General Sherman had just completed his devastating march from Savannah, Georgia, to North Carolina, defeating Confederate efforts to stop his onward progress. George P. A. Healy, The Peacemakers, 1868, oil on canvas, 31 1/2 x 39 1/4 inches (Chicago History Museum)

This painting captures a solemn meeting on March 27, 1865, between Abraham Lincoln, and, left to right, his generals William T. Sherman and Ulysses S. Grant, and Admiral David Porter, aboard the ship River Queen at City Point, Virginia. The River Queen was General Grant’s headquarters during the last months of the war, and this scene occurred as the war neared its end. General Sherman had just completed his devastating march from Savannah, Georgia, to North Carolina, defeating Confederate efforts to stop his onward progress. George P. A. Healy, The Peacemakers, 1868, oil on canvas, 31 1/2 x 39 1/4 inches (Chicago History Museum) These were the three most powerful Civil War military leaders at the end of the war. The seated man in the center is Abraham Lincoln, and the standing man on the left is General Ulysses S. Grant. The third figure is Edwin M. Stanton, Lincoln’s Secretary of War. Rogers was one of the first artists to make sculpture affordable for middle-class Americans. By casting sculptures like this one in plaster, rather than bronze, Rogers lowered the cost of the works considerably. The sculptures’ small size allowed people to display them in a typical home. John Rogers, The Council of War, c. 1873–95, painted cast plaster, 24 x 15 x 13 Inches (Chicago Public Library)

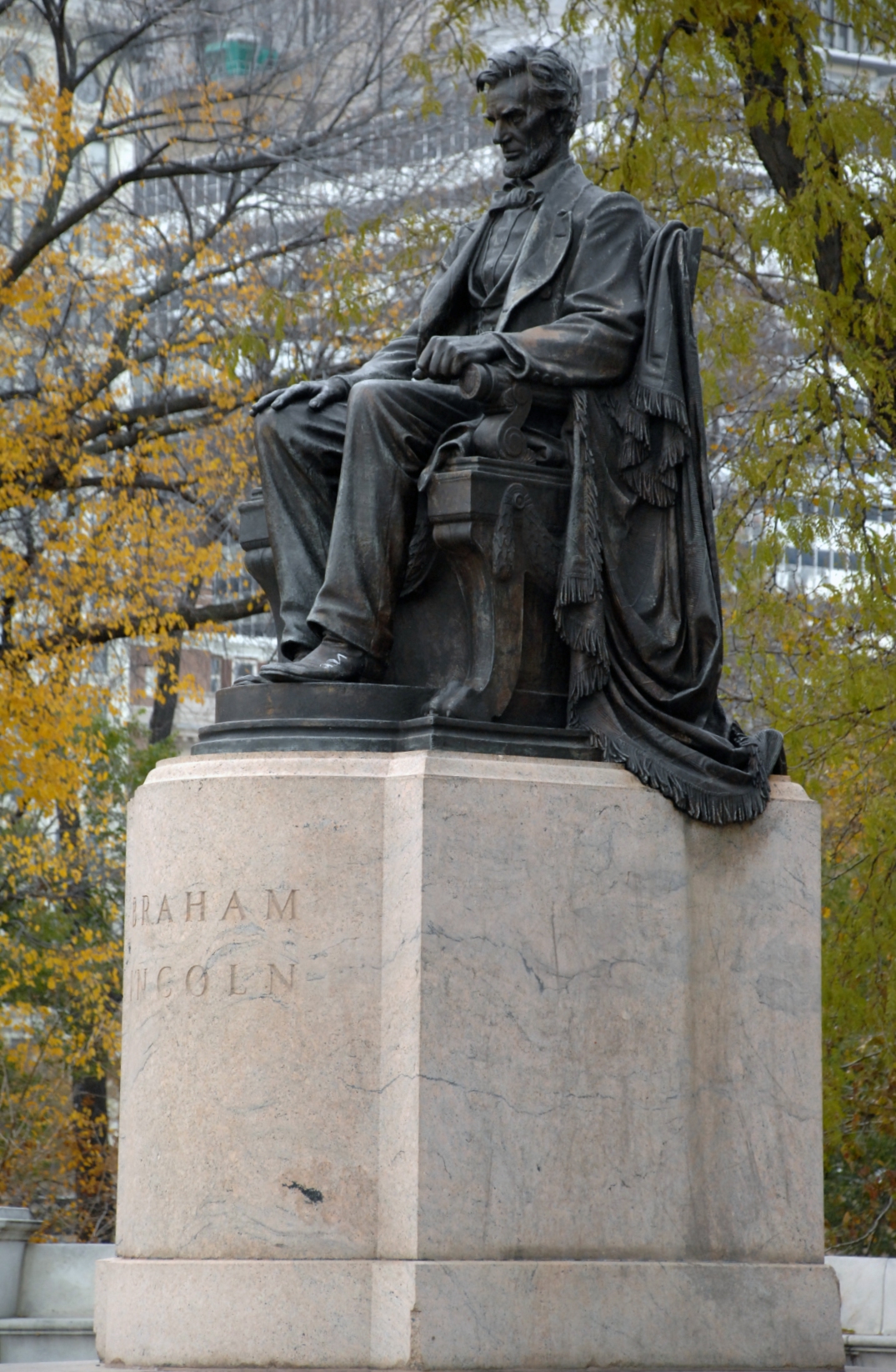

These were the three most powerful Civil War military leaders at the end of the war. The seated man in the center is Abraham Lincoln, and the standing man on the left is General Ulysses S. Grant. The third figure is Edwin M. Stanton, Lincoln’s Secretary of War. Rogers was one of the first artists to make sculpture affordable for middle-class Americans. By casting sculptures like this one in plaster, rather than bronze, Rogers lowered the cost of the works considerably. The sculptures’ small size allowed people to display them in a typical home. John Rogers, The Council of War, c. 1873–95, painted cast plaster, 24 x 15 x 13 Inches (Chicago Public Library) This sculpture depicts President Abraham Lincoln standing thoughtfully in front of an enormous chair, as if about to give a speech. There are verses from some of Lincoln’s most famous speeches inscribed on the exedra and also cast into the two bronze globes on each side of the steps leading up to the platform. Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Stanford White, Abraham Lincoln: The Man (The Standing Lincoln), 1887, bronze figure on granite exedra, 25 x 100 x 50 feet (Chicago Park District)

This sculpture depicts President Abraham Lincoln standing thoughtfully in front of an enormous chair, as if about to give a speech. There are verses from some of Lincoln’s most famous speeches inscribed on the exedra and also cast into the two bronze globes on each side of the steps leading up to the platform. Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Stanford White, Abraham Lincoln: The Man (The Standing Lincoln), 1887, bronze figure on granite exedra, 25 x 100 x 50 feet (Chicago Park District) The sculptor, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, used life masks, actual molds of Lincoln’s face and hands, as the basis of this work. Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Stanford White, Abraham Lincoln: The Man (The Standing Lincoln), 1887, bronze figure on granite exedra, 25 x 100 x 50 feet (Chicago Park District)

The sculptor, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, used life masks, actual molds of Lincoln’s face and hands, as the basis of this work. Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Stanford White, Abraham Lincoln: The Man (The Standing Lincoln), 1887, bronze figure on granite exedra, 25 x 100 x 50 feet (Chicago Park District) In this sculpture, Saint-Gaudens depicted Abraham Lincoln looking very stately, sitting on a throne-like chair draped with an American flag. But the president looks lonely, and once again, the artist gave him a very somber expression—as though Lincoln was feeling deeply burdened by the Civil War. Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Stanford White, Abraham Lincoln, Head of State, cast 1908, installed 1926, bronze, granite, and marble, 35 x 150 x 60 feet (Chicago Park District)

In this sculpture, Saint-Gaudens depicted Abraham Lincoln looking very stately, sitting on a throne-like chair draped with an American flag. But the president looks lonely, and once again, the artist gave him a very somber expression—as though Lincoln was feeling deeply burdened by the Civil War. Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Stanford White, Abraham Lincoln, Head of State, cast 1908, installed 1926, bronze, granite, and marble, 35 x 150 x 60 feet (Chicago Park District) Augustus Saint-Gaudens was an Irish immigrant who grew up in New York and apprenticed as cameo-cutter before becoming one of America’s most famous artists. As a teenager, Saint-Gaudens had seen Abraham Lincoln a couple of times. Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Stanford White, Abraham Lincoln, Head of State, cast 1908, installed 1926, bronze, granite, and marble, 35 x 150 x 60 feet (Chicago Park District)

Augustus Saint-Gaudens was an Irish immigrant who grew up in New York and apprenticed as cameo-cutter before becoming one of America’s most famous artists. As a teenager, Saint-Gaudens had seen Abraham Lincoln a couple of times. Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Stanford White, Abraham Lincoln, Head of State, cast 1908, installed 1926, bronze, granite, and marble, 35 x 150 x 60 feet (Chicago Park District) Rail-splitting means using a large maul (mallet) and wedges to split logs into thinner pieces. It was hard work done by people living on the prairie mostly to make fences to mark property. When Abraham Lincoln ran for President, his campaign emphasized that he had done this kind of work so common people could relate to him. Charles J. Mulligan, Lincoln the Rail-splitter, temporary version exhibited in 1909, cast in bronze in 1911, bronze figure on granite base, Garfield Park, 14 x 4 x 4 feet (Chicago Park District)

Rail-splitting means using a large maul (mallet) and wedges to split logs into thinner pieces. It was hard work done by people living on the prairie mostly to make fences to mark property. When Abraham Lincoln ran for President, his campaign emphasized that he had done this kind of work so common people could relate to him. Charles J. Mulligan, Lincoln the Rail-splitter, temporary version exhibited in 1909, cast in bronze in 1911, bronze figure on granite base, Garfield Park, 14 x 4 x 4 feet (Chicago Park District) This is a small version of a much larger bronze sculpture that sits atop a marble base in a Lincoln, Nebraska memorial, where the Gettysburg Address, the speech that Lincoln delivered after the battle of Gettysburg in 1863, is carved into a slab of granite behind the figure. Daniel Chester French, Abraham Lincoln, 1912 (modeled in 1912, cast after 1912), bronze (The Art Institute of Chicago)

This is a small version of a much larger bronze sculpture that sits atop a marble base in a Lincoln, Nebraska memorial, where the Gettysburg Address, the speech that Lincoln delivered after the battle of Gettysburg in 1863, is carved into a slab of granite behind the figure. Daniel Chester French, Abraham Lincoln, 1912 (modeled in 1912, cast after 1912), bronze (The Art Institute of Chicago) Daniel Chester French was commissioned in 1914 to create a large monumental sculpture of President Lincoln for a memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. He based his work on photographs and plaster casts made of Lincoln’s face and hands before his death. The bronze sculpture you see here is one of a number of smaller copies French made to advertise his craftsmanship as well as make money, as Lincoln memorabilia was quite popular. Daniel Chester French, Abraham Lincoln, 1916 (modeled in 1916, cast after 1916), bronze, 33 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago)

Daniel Chester French was commissioned in 1914 to create a large monumental sculpture of President Lincoln for a memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. He based his work on photographs and plaster casts made of Lincoln’s face and hands before his death. The bronze sculpture you see here is one of a number of smaller copies French made to advertise his craftsmanship as well as make money, as Lincoln memorabilia was quite popular. Daniel Chester French, Abraham Lincoln, 1916 (modeled in 1916, cast after 1916), bronze, 33 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago) Charles Keck did not depict Abraham Lincoln as a famous statesman; rather, he appears as a clean-shaven young man wearing what looks like a work shirt, with sleeves rolled up. This sculpture gives you the feeling that Lincoln has just finished work, found a comfortable tree stump to sit on, grabbed his book, and is lost in his law studies. Lincoln came from a poor family and was mostly self-taught. Charles Keck, The Young Lincoln, c. 1945, bronze sculpture on a concrete base, 12 x 8 x 8 feet (on loan to the Chicago Park District from the Chicago Public Library)

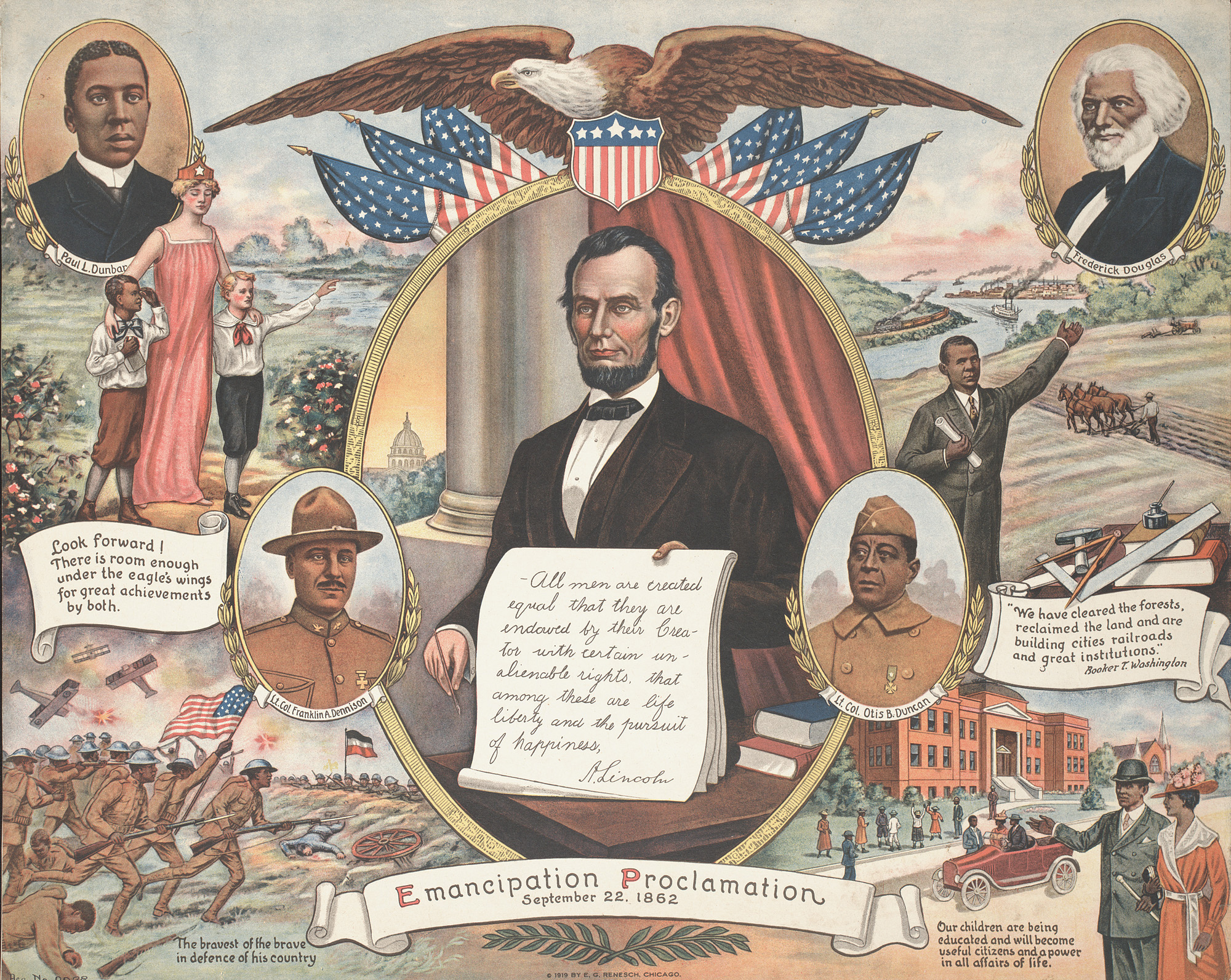

Charles Keck did not depict Abraham Lincoln as a famous statesman; rather, he appears as a clean-shaven young man wearing what looks like a work shirt, with sleeves rolled up. This sculpture gives you the feeling that Lincoln has just finished work, found a comfortable tree stump to sit on, grabbed his book, and is lost in his law studies. Lincoln came from a poor family and was mostly self-taught. Charles Keck, The Young Lincoln, c. 1945, bronze sculpture on a concrete base, 12 x 8 x 8 feet (on loan to the Chicago Park District from the Chicago Public Library) At the center of this colorful poster is Abraham Lincoln, holding a document showing the famous phrase “All men are created equal” from the Declaration of Independence. The date, September 22, 1862, just below Lincoln, refers to the day on which Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, declaring freedom for all enslaved people in the rebel states unless the Confederacy returned to the United States by January 1, 1863. Alongside Lincoln are portraits of two Black officers who served in World War I. E. G. Renesch, Emancipation Proclamation, 1919, broadside, 16 x 20 inches (Chicago History Museum)

At the center of this colorful poster is Abraham Lincoln, holding a document showing the famous phrase “All men are created equal” from the Declaration of Independence. The date, September 22, 1862, just below Lincoln, refers to the day on which Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, declaring freedom for all enslaved people in the rebel states unless the Confederacy returned to the United States by January 1, 1863. Alongside Lincoln are portraits of two Black officers who served in World War I. E. G. Renesch, Emancipation Proclamation, 1919, broadside, 16 x 20 inches (Chicago History Museum) Edmonia Lewis, an American sculptor who had both Black and Indigenous ancestry and who worked in Rome, created an emancipation group called Forever Free soon after the conclusion of the Civil War. Lewis’s sculpture centers on the experience of a Black man and woman at the moment of emancipation. Overcoming the common visual trope of the kneeling slave begging for freedom seen in much abolitionist imagery, Lewis depicts a formerly enslaved man raising one arm with a broken shackle in a victorious attitude, his other hand resting on the shoulder of a kneeling woman whose own hands are clasped in prayer as if thanking God for the gift of freedom. With a protective, independent male figure and chaste, pious female figure, Lewis suggested that this newly free Black couple is finally able to participate in the family framework that was prized in the Victorian era. Another proposed sculpture group, white female sculptor Harriet Hosmer’s unrealized designs for an emancipation memorial, featured a sculptural cycle of Black history with four standing male figures at each corner, representing kidnapping, enslavement, self-emancipation, and military service. The figures are shown standing and appear as dignified and active agents in their own destinies. Left: Edmonia Lewis, Forever Free, 1867, marble, 106 cm high (Howard University Gallery of Art); right: Harriet Hosmer, early design for Freedmen’s Memorial to Lincoln, 1868

Edmonia Lewis, an American sculptor who had both Black and Indigenous ancestry and who worked in Rome, created an emancipation group called Forever Free soon after the conclusion of the Civil War. Lewis’s sculpture centers on the experience of a Black man and woman at the moment of emancipation. Overcoming the common visual trope of the kneeling slave begging for freedom seen in much abolitionist imagery, Lewis depicts a formerly enslaved man raising one arm with a broken shackle in a victorious attitude, his other hand resting on the shoulder of a kneeling woman whose own hands are clasped in prayer as if thanking God for the gift of freedom. With a protective, independent male figure and chaste, pious female figure, Lewis suggested that this newly free Black couple is finally able to participate in the family framework that was prized in the Victorian era. Another proposed sculpture group, white female sculptor Harriet Hosmer’s unrealized designs for an emancipation memorial, featured a sculptural cycle of Black history with four standing male figures at each corner, representing kidnapping, enslavement, self-emancipation, and military service. The figures are shown standing and appear as dignified and active agents in their own destinies. Left: Edmonia Lewis, Forever Free, 1867, marble, 106 cm high (Howard University Gallery of Art); right: Harriet Hosmer, early design for Freedmen’s Memorial to Lincoln, 1868 This monument shows Lincoln holding the Emancipation Proclamation and bestowing freedom on a semi-nude Black man crouched at his feet, implying that freedom was a gift given by Lincoln to the grateful enslaved. This portrayal eliminates the agency of Black people in obtaining their own freedom and it presents emancipation as a single event rather than an ongoing process of securing equality and citizenship. It also freezes the Black man in a powerless pose, forever locked in a state of subservience—while suggesting that he ought to be grateful for it. Thomas Ball, Freedmen’s Memorial to Abraham Lincoln, 1876, Lincoln Park, Washington D.C. (photo: Renée Ater)

This monument shows Lincoln holding the Emancipation Proclamation and bestowing freedom on a semi-nude Black man crouched at his feet, implying that freedom was a gift given by Lincoln to the grateful enslaved. This portrayal eliminates the agency of Black people in obtaining their own freedom and it presents emancipation as a single event rather than an ongoing process of securing equality and citizenship. It also freezes the Black man in a powerless pose, forever locked in a state of subservience—while suggesting that he ought to be grateful for it. Thomas Ball, Freedmen’s Memorial to Abraham Lincoln, 1876, Lincoln Park, Washington D.C. (photo: Renée Ater) Statues of Abraham Lincoln have been sites of recent controversy, both because of Lincoln’s actions towards Indigenous peoples and because many Lincoln statues seem to depict him “granting” emancipation to passive Black people. Left: Photograph of the Emancipation statue, Boston, Massachusetts, c. 1877–95, albumen print (Boston Public Library); right: removal of the statue from Park Square, Boston (courtesy Boston City TV)

Statues of Abraham Lincoln have been sites of recent controversy, both because of Lincoln’s actions towards Indigenous peoples and because many Lincoln statues seem to depict him “granting” emancipation to passive Black people. Left: Photograph of the Emancipation statue, Boston, Massachusetts, c. 1877–95, albumen print (Boston Public Library); right: removal of the statue from Park Square, Boston (courtesy Boston City TV) On December 29, 2020, Boston officials remove a statue of Abraham Lincoln standing above a kneeling emancipated person. The Boston mayor’s office told the press that, “The decision for removal acknowledges the statue’s role in perpetuating harmful prejudices and obscuring the role of Black Americans in shaping the nation’s fight for freedom.” Thomas Ball, Emancipation Group (recasting of Freedmen's Memorial), 1879, bronze (photo © Nancy Lane/MediaNews Group/Boston Herald)

On December 29, 2020, Boston officials remove a statue of Abraham Lincoln standing above a kneeling emancipated person. The Boston mayor’s office told the press that, “The decision for removal acknowledges the statue’s role in perpetuating harmful prejudices and obscuring the role of Black Americans in shaping the nation’s fight for freedom.” Thomas Ball, Emancipation Group (recasting of Freedmen's Memorial), 1879, bronze (photo © Nancy Lane/MediaNews Group/Boston Herald) On October 11, 2020, protesters participating in the Indigenous Peoples Day of Rage in Portland, Oregon, toppled a statue of Abraham Lincoln, spray painting its hands blood red and its plinth with reminders of Lincoln’s role in suppressing Indigenous peoples: “LAND BACK,” a protester scrawled on one side of the stone marker, connecting Lincoln with the accelerated dispossession of Native lands that occurred during and after the Civil War, and “DAKOTA 38” on another side, referencing the mass execution of Dakota men that Lincoln ordered in 1862. George Fite Waters, Abraham Lincoln, 1927, bronze, 10 feet high (photo © Sergio Olmos)

On October 11, 2020, protesters participating in the Indigenous Peoples Day of Rage in Portland, Oregon, toppled a statue of Abraham Lincoln, spray painting its hands blood red and its plinth with reminders of Lincoln’s role in suppressing Indigenous peoples: “LAND BACK,” a protester scrawled on one side of the stone marker, connecting Lincoln with the accelerated dispossession of Native lands that occurred during and after the Civil War, and “DAKOTA 38” on another side, referencing the mass execution of Dakota men that Lincoln ordered in 1862. George Fite Waters, Abraham Lincoln, 1927, bronze, 10 feet high (photo © Sergio Olmos) This work by Travis Blackbird (Omaha/Oglala Lakota) includes an image of Lincoln atop a map of the state of Minnesota. In 1862, Dakotas were starving in Minnesota after white settlers pushed them off their lands. A faction of Dakota men attacked the reservation administration building where government agents had broken the terms of the treaty by refusing to sell them food, and the uprising escalated into all-out warfare. After they were defeated at the Battle of Wood Lake in late September, the Dakotas were subjected to military trials that resulted in sentencing more than 300 men to death. Abraham Lincoln commuted the sentences of most but signed an order to execute 38 Dakota men, which was the largest mass execution in U.S. history. Travis Blackbird, ISTA-SKA (and detail at right), 2017 (© Travis Blackbird used by permission)

This work by Travis Blackbird (Omaha/Oglala Lakota) includes an image of Lincoln atop a map of the state of Minnesota. In 1862, Dakotas were starving in Minnesota after white settlers pushed them off their lands. A faction of Dakota men attacked the reservation administration building where government agents had broken the terms of the treaty by refusing to sell them food, and the uprising escalated into all-out warfare. After they were defeated at the Battle of Wood Lake in late September, the Dakotas were subjected to military trials that resulted in sentencing more than 300 men to death. Abraham Lincoln commuted the sentences of most but signed an order to execute 38 Dakota men, which was the largest mass execution in U.S. history. Travis Blackbird, ISTA-SKA (and detail at right), 2017 (© Travis Blackbird used by permission) Although Abraham Lincoln invited a delegation of Plains peoples to the White House in 1863—whom he urged not to ally with Confederates, and who in turn urged him to honor land treaties—he continued ongoing U.S. government efforts to force Indigenous people onto reservations. There was no equivalent to the Emancipation Proclamation for Indigenous peoples. Mathew Brady, Delegation of Plains peoples to the White House, 1863, photograph (White House)

Although Abraham Lincoln invited a delegation of Plains peoples to the White House in 1863—whom he urged not to ally with Confederates, and who in turn urged him to honor land treaties—he continued ongoing U.S. government efforts to force Indigenous people onto reservations. There was no equivalent to the Emancipation Proclamation for Indigenous peoples. Mathew Brady, Delegation of Plains peoples to the White House, 1863, photograph (White House) In 1870, Robert E. Lee, the leader of the Confederate Army, died and white women of the South—the wives, widows, and daughters of Confederate veterans—vowed immediately that Lee should have a monument equal to his southern cultural status. In 1890, an equestrian statue of Lee was unveiled in Richmond, Virginia—the first monument to a Confederate leader on Richmond’s Monument Avenue. In 2020 Black Minneapolis resident George Floyd was murdered by a white police officer, prompting nationwide protests against the everyday violence and discrimination Black Americans face across the United States. Protesters often targeted public monuments as symbols of white supremacy and Monument Avenue was slowly depopulated of its bronze and marble monuments to Confederates. In September 2021, Lee was removed from its place of honor on Monument Avenue and shipped to a warehouse. Antonin Mercié, Robert E. Lee Monument, 1890, bronze, removed from Monument Avenue, Richmond Virginia, September 9, 2021 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In 1870, Robert E. Lee, the leader of the Confederate Army, died and white women of the South—the wives, widows, and daughters of Confederate veterans—vowed immediately that Lee should have a monument equal to his southern cultural status. In 1890, an equestrian statue of Lee was unveiled in Richmond, Virginia—the first monument to a Confederate leader on Richmond’s Monument Avenue. In 2020 Black Minneapolis resident George Floyd was murdered by a white police officer, prompting nationwide protests against the everyday violence and discrimination Black Americans face across the United States. Protesters often targeted public monuments as symbols of white supremacy and Monument Avenue was slowly depopulated of its bronze and marble monuments to Confederates. In September 2021, Lee was removed from its place of honor on Monument Avenue and shipped to a warehouse. Antonin Mercié, Robert E. Lee Monument, 1890, bronze, removed from Monument Avenue, Richmond Virginia, September 9, 2021 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) Confederate monuments were focal points for instruction. Memorial days and national holidays (after the era of Reconciliation) occasioned community-wide gatherings around the statues. The monument builders also intended these statutes to have an instructive function for the Black citizens: to intimidate Black voters and to claim public spaces for white citizens only. Huestis Pratt Cook, Human Confederate Flag, c. 1907. Postcard depicting a “human Confederate flag” created by arranging children at a Confederate Memorial Day celebration under the Robert E. Lee statue on Monument Avenue in Richmond (Library of Virginia)

Confederate monuments were focal points for instruction. Memorial days and national holidays (after the era of Reconciliation) occasioned community-wide gatherings around the statues. The monument builders also intended these statutes to have an instructive function for the Black citizens: to intimidate Black voters and to claim public spaces for white citizens only. Huestis Pratt Cook, Human Confederate Flag, c. 1907. Postcard depicting a “human Confederate flag” created by arranging children at a Confederate Memorial Day celebration under the Robert E. Lee statue on Monument Avenue in Richmond (Library of Virginia) Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia was the original site of five Confederate monuments that served as a testament to the “Lost Cause” mythology, which emerged in the years following the end of the Civil War. The myth perpetuates the falsehood that the war was fought to defend the Southern states’ rights instead of the institution of slavery, heroizes the efforts of Confederate soldiers and leaders, and celebrates the white supremacist reversal of gains made by African Americans during Reconstruction (1865–77). Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia was the original site of five Confederate monuments that served as a testament to the “Lost Cause” mythology, which emerged in the years following the end of the Civil War. The myth perpetuates the falsehood that the war was fought to defend the Southern states’ rights instead of the institution of slavery, heroizes the efforts of Confederate soldiers and leaders, and celebrates the white supremacist reversal of gains made by African Americans during Reconstruction (1865–77). Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) Two views of the Robert E. Lee monument in Richmond, Virginia. On the left, a crowd gathers to watch the unveiling of the equestrian statue of Lee in 1890. On the right, the statue with graffiti after the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020. The statue was removed from Monument Avenue in Richmond on September 9, 2021. Antonin Mercié, Robert E. Lee Monument, 1890, bronze (photo left: The Valentine; photo right: Mk17b, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Two views of the Robert E. Lee monument in Richmond, Virginia. On the left, a crowd gathers to watch the unveiling of the equestrian statue of Lee in 1890. On the right, the statue with graffiti after the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020. The statue was removed from Monument Avenue in Richmond on September 9, 2021. Antonin Mercié, Robert E. Lee Monument, 1890, bronze (photo left: The Valentine; photo right: Mk17b, CC BY-SA 4.0) Georgia redesigned its state flag in 1956 to include the “stars and bars” of the Confederate battle flag in response to the Supreme Court ruling in Brown vs Board of Education, while South Carolina hoisted the battle flag of the Confederacy above their state house in 1961, ostensibly to celebrate the Civil War’s centennial. It was not removed until 2015, after a white supremacist murdered nine Black churchgoers in Charleston and activist Bree Newsome scaled the flagpole on the state capitol grounds to remove it, forcing the state to take action. Activist takes down Confederate flag outside South Carolina capitol, Reuters/Adam Anderson Photo, June 27, 2015

Georgia redesigned its state flag in 1956 to include the “stars and bars” of the Confederate battle flag in response to the Supreme Court ruling in Brown vs Board of Education, while South Carolina hoisted the battle flag of the Confederacy above their state house in 1961, ostensibly to celebrate the Civil War’s centennial. It was not removed until 2015, after a white supremacist murdered nine Black churchgoers in Charleston and activist Bree Newsome scaled the flagpole on the state capitol grounds to remove it, forcing the state to take action. Activist takes down Confederate flag outside South Carolina capitol, Reuters/Adam Anderson Photo, June 27, 2015 The monumental relief sculpture of confederate leaders Robert E. Lee, Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, and Jefferson Davis at Stone Mountain Park, Georgia, is a potent symbol of white supremacy which has continued to define southern United States culture since before the Civil War. Still today, the site reflects an ongoing conversation in Georgia and across the United States about the history, legacy, and symbolism of the Confederacy and Civil War. Gutzon Borglum, Augustus Lukeman, Julian Harris, Walter Hancock, and Roy Faulkner (sculptors), Confederate Memorial, Stone Mountain, Georgia, completed in 1970 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The monumental relief sculpture of confederate leaders Robert E. Lee, Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, and Jefferson Davis at Stone Mountain Park, Georgia, is a potent symbol of white supremacy which has continued to define southern United States culture since before the Civil War. Still today, the site reflects an ongoing conversation in Georgia and across the United States about the history, legacy, and symbolism of the Confederacy and Civil War. Gutzon Borglum, Augustus Lukeman, Julian Harris, Walter Hancock, and Roy Faulkner (sculptors), Confederate Memorial, Stone Mountain, Georgia, completed in 1970 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) John Brown was a passionate abolitionist who organized with his countrymen to fight against slavery. Note the covered wagons of pioneers moving west in the background, the flat landscape, and the tornado—details suggesting that the setting is Kansas. By 1855, Kansas had become a hotbed of conflict between abolitionists and pro-slavery forces. Later, Brown led an attack on the Federal Arsenal at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia in an attempt to trigger and arm a slave insurrection. Curry, a Kansas native, made this print while painting a mural for the Kansas State Capitol in Topeka that featured a similar likeness of Brown. The mural was created between 1937 and 1942, a time when the country looked back on its past to weather the financial and agricultural calamities of the Great Depression. John Steuart Curry, John Brown, 1939, lithograph, 14 3/4 x 10 7/8 inches (Terra Foundation for American Art)

John Brown was a passionate abolitionist who organized with his countrymen to fight against slavery. Note the covered wagons of pioneers moving west in the background, the flat landscape, and the tornado—details suggesting that the setting is Kansas. By 1855, Kansas had become a hotbed of conflict between abolitionists and pro-slavery forces. Later, Brown led an attack on the Federal Arsenal at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia in an attempt to trigger and arm a slave insurrection. Curry, a Kansas native, made this print while painting a mural for the Kansas State Capitol in Topeka that featured a similar likeness of Brown. The mural was created between 1937 and 1942, a time when the country looked back on its past to weather the financial and agricultural calamities of the Great Depression. John Steuart Curry, John Brown, 1939, lithograph, 14 3/4 x 10 7/8 inches (Terra Foundation for American Art) On the left of this painted scene, a Black soldier raises his sword and leads men in a charge. Colonel Robert Gould Shaw is seen dying in the lower right corner of the image. The men belong to the 54th Massachusetts, United States Colored Troops. Up to this point, Black soldiers had been included in only a few battles; Fort Wagner convinced white northerners of their capabilities in the war effort. Martyl (Suzanne Schweig Langsdorf), Col. Robert G. Shaw dying at the Battle of Fort Wagner, 1940, gouache on masonite board, 28.81 x 19.75 inches (DuSable Museum of African American History)

On the left of this painted scene, a Black soldier raises his sword and leads men in a charge. Colonel Robert Gould Shaw is seen dying in the lower right corner of the image. The men belong to the 54th Massachusetts, United States Colored Troops. Up to this point, Black soldiers had been included in only a few battles; Fort Wagner convinced white northerners of their capabilities in the war effort. Martyl (Suzanne Schweig Langsdorf), Col. Robert G. Shaw dying at the Battle of Fort Wagner, 1940, gouache on masonite board, 28.81 x 19.75 inches (DuSable Museum of African American History) In this painting, Abraham Lincoln takes the stage in Alton, Illinois. It is 1858, and this event is the last of seven debates Lincoln had with his rival for the U. S. Senate, Stephen A. Douglas, the famous Democratic Party leader. The men addressed the heated question of slavery in the territories. Douglas won the senate seat, but Lincoln’s speeches during the debates made him a political rising star, contributing to his victory as the Republican candidate for President in 1860. Carter made his painting during the Civil Rights Movement. William Sylvester Carter, Lincoln Douglas Debate at Alton, Illinois, 1963, oil on canvas 29.5 x 39.62 inches (DuSable Museum of African American History)

In this painting, Abraham Lincoln takes the stage in Alton, Illinois. It is 1858, and this event is the last of seven debates Lincoln had with his rival for the U. S. Senate, Stephen A. Douglas, the famous Democratic Party leader. The men addressed the heated question of slavery in the territories. Douglas won the senate seat, but Lincoln’s speeches during the debates made him a political rising star, contributing to his victory as the Republican candidate for President in 1860. Carter made his painting during the Civil Rights Movement. William Sylvester Carter, Lincoln Douglas Debate at Alton, Illinois, 1963, oil on canvas 29.5 x 39.62 inches (DuSable Museum of African American History) The state of Illinois commissioned this painting in celebration of the centennial (the 100-year anniversary) of the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation. In creating it, artist Gus Nall imagines the scene during President Lincoln’s April 4, 1865 visit to the conquered Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia. This painting’s focus on equality is particularly important when you think about when it was made: during the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. Gus Nall, Lincoln Speaks to Freedmen on the Steps of the Capital at Richmond, 1963, oil on canvas, 39.62 x 29.5 inches (DuSable Museum of African American History)