Edward Hicks’s The Peaceable Kingdom, 1826 will be useful for the study of:

- The history of Quakers in the United States

- The evolving relationship between the colonies (and later the United States) and the Native Americans

- William Penn and the history of Pennsylvania

- The Middle Colonies

By the end of this lesson, students should be able to:

- Discuss Hicks’s The Peaceable Kingdom as a primary document that links to the specific historical context of the history of Pennsylvania and Quakers in the United States

- Apply the tools of visual analysis to support interpretation of the artwork

- Understand some of the basic tenets of the Quaker faith

- Articulate the difference between the style of Edward Hicks, and artists who were trained as artists (not as sign-painters) as seen in the painting

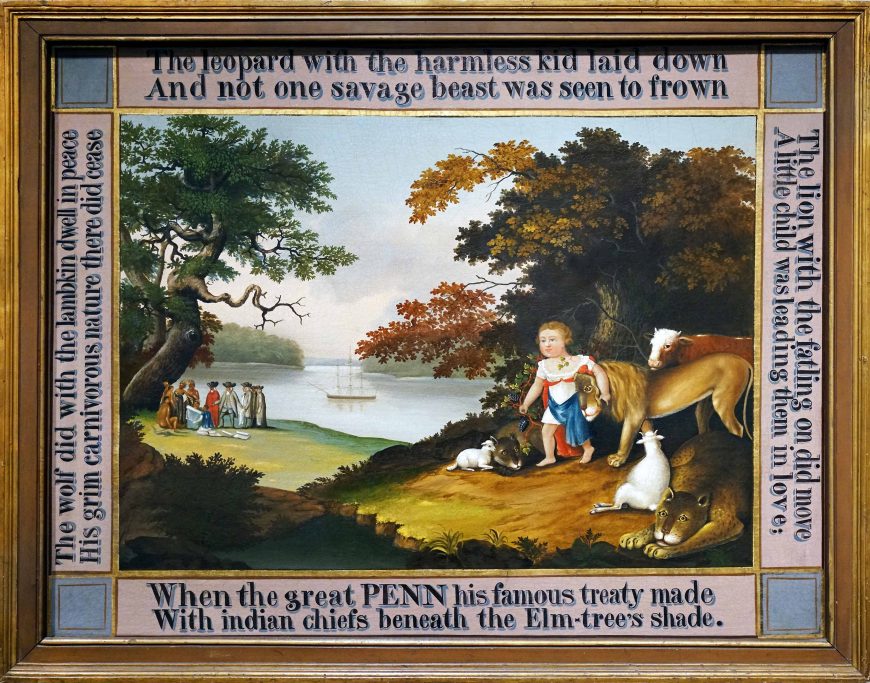

Edward Hicks, The Peaceable Kingdom, 1826, oil on canvas, 83.5 x 106 cm (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

1. Look closely at the painting

Look closely at Edward Hicks’s The Peaceable Kingdom (zoomable images available for download for teaching)

Questions to ask:

- Describe the two groups of figures/animals you see. Can you identify each of the animals represented?

- How does the artist help us to understand that he is drawing a parallel between these two groups, even though one is biblical and the other historical?

- Describe the landscape — what season is it? What is the weather?

- Does the inscription around the frame help you to understand the painting?

2. Watch the video

The video “Hicks’The Peaceable Kingdom as Pennsylvania parable” is about 7 minutes in length. Ideally, the video should provide an active rather than a passive classroom experience. Please feel free to stop the video to respond to student questions, to underscore or develop issues, to define vocabulary, or to look closely at parts of the painting that are being discussed. Key points, a self-diagnostic quiz, and high resolution photographs with details of the work are provided to support the video.

3. Read about the painting and its historical context

The beginnings of the state of Pennsylvania

In 1664, the Duke of York granted the area between the Hudson and Delaware rivers to two English noblemen. These lands were split into two distinct colonies, East Jersey and West Jersey. One of West Jersey’s proprietors included William Penn. The ambitious Penn wanted his own, larger colony, the lands for which would be granted by both Charles II and the Duke of York. Pennsylvania consisted of about forty-five thousand square miles west of the Delaware River and the former New Sweden. Penn was a member of the Society of Friends, otherwise known as Quakers, and he intended his colony to be a “colony of Heaven for the children of Light.”[1]

Like New England’s aspirations to be a City Upon a Hill, Pennsylvania was to be an example of godliness. But Penn’s dream was to create not a colony of unity but rather a colony of harmony. He noted in 1685 that “the people are a collection of diverse nations in Europe, as French, Dutch, Germans, Swedes, Danes, Finns, Scotch, and English; and of the last equal to all the rest.”[2] Because Quakers in Pennsylvania extended to others in America the same rights they had demanded for themselves in England, the colony attracted a diverse collection of migrants. Slavery was particularly troublesome for some pacifist Quakers of Pennsylvania on the grounds that it required violence. In 1688, members of the Society of Friends in Germantown, outside Philadelphia, signed a petition protesting the institution of slavery among fellow Quakers.

The Walking Purchase (also known as The Walking Treaty)

If a colony existed where peace with Indians might continue, it would be Pennsylvania. At the colony’s founding, William Penn created a Quaker religious imperative for the peaceful treatment of Indians. While Penn never doubted that the English would appropriate Native lands, he demanded that his colonists obtain Indian territories through purchase rather than violence. Though Pennsylvanians maintained relatively peaceful relations with Native Americans, increased immigration and booming land speculation increased the demand for land. Coercive and fraudulent methods of negotiation became increasingly prominent. The Walking Purchase of 1737 was emblematic of both colonists’ desire for cheap land and the changing relationship between Pennsylvanians and their Native neighbors.

Through treaty negotiation in 1737, Native Delaware leaders agreed to sell Pennsylvania all of the land that a man could walk in a day and a half, a common measurement used by Delawares in evaluating distances. John and Thomas Penn, joined by the land speculator and longtime friend of the Penns James Logan, hired a team of skilled runners to complete the “walk” on a prepared trail. The runners traveled from Wrightstown to the present-day town of Jim Thorpe, and proprietary officials then drew the new boundary line perpendicular to the runners’ route, extending northeast to the Delaware River. The colonial government thus measured out a tract much larger than the Delaware had originally intended to sell, roughly 1,200 square miles. As a result, Delaware-proprietary relations suffered. Many Delaware left the lands in question and migrated westward to join Shawnee and other Delaware already living in the Ohio Valley. There they established diplomatic and trade relationships with the French. Memories of the suspect purchase endured into the 1750s and became a chief point of contention between the Pennsylvanian government and the Delaware during the upcoming Seven Years’ War.27

1. Quoted in David Hackett Fischer, Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), 459.

2. Albert Cook Myers, ed., Narratives of Early Pennsylvania, West New Jersey, and Delaware, 1630–1707 (New York: Scribner, 1912), 260.

From “British North America,” The American Yawp, Stanford University Press (CC BY-SA 4.0)

4. Discussion question

Though William Penn followed his Quaker beliefs in establishing peace with the Native Americans, he also assumed that the English settlers would appropriate their land. What other examples have you studied in American history that demonstrates the European settlers’ assumption of superiority and right to take control of large sections of the North American continent?

5. Research question

Quakers have been both persecuted and accepted at different times in American history. Watch these three videos on this topic:

- A Puritan Court Cupboard (1665-73), owned by Dr. Thomas Prence, governor of Plymouth Colony, who passed a series of laws designed to punish or drive Quakers out of the colony.

- Copley’s Portrait of Mr. and Mrs. Mifflin (1773) — the Mifflins were Quakers who advocated for the boycott of British goods that helped to further the ideals of the American Revolution.

- Hicks’s A Peaceable Kingdom (1823) painted by a Quaker artist to express Quaker ideals of peaceful co-existence.

Discuss the beliefs of the Quakers and the different ways they have been accepted (or not) into the culture of the American Colonies and the United States.

6. Bibliography

This painting at the Philadelphia Museum of Art

Learn about the Middle Colonies at Khan Academy

“Our First Friends, The Early Quakers” from Pennsylvania Heritage

1681-1776: The Quaker Province—The Founding of Pennsylvania (William Penn and the Quakers)

Pencak, William, and Daniel K. Richter, eds., Friends and Enemies in Penn’s Woods: Indians, Colonists, and the Racial Construction of Pennsylvania (University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2004).

William Penn And His Holy Experiment from the Library of Congress

From Magna Carta on Trial to the Holy Experiment

Religion and the Founding of the American Republic from the Library of Congress