Wanted: stunning view

Cliff dwellings, Ancestral Puebloan, 450–1300 C.E., sandstone, Mesa Verde National Park, (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

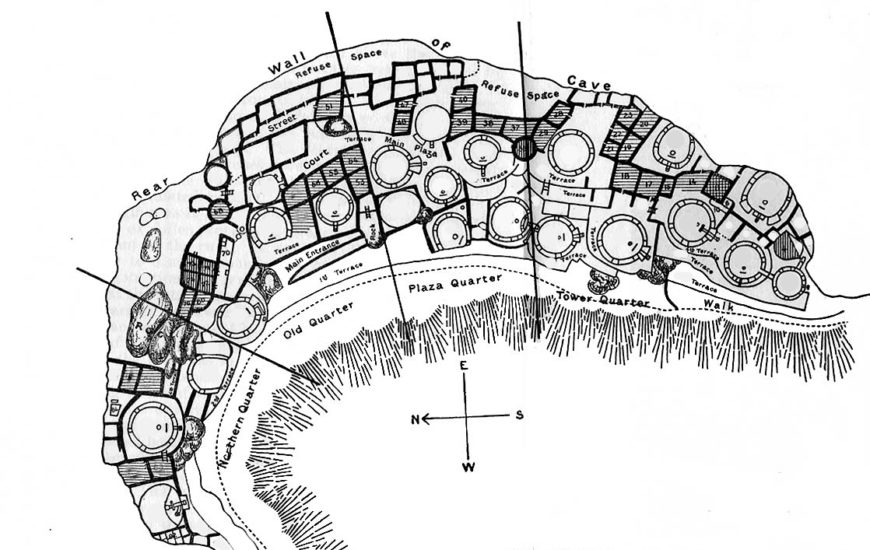

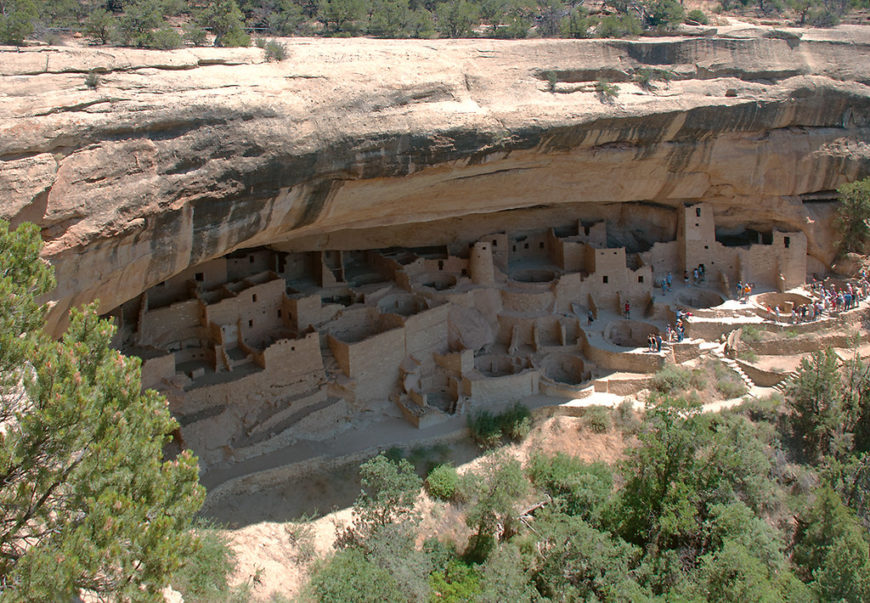

Imagine living in a home built into the side of a cliff. The Ancestral Puebloan peoples (formerly known as the Anasazi) did just that in some of the most remarkable structures still in existence today. Beginning after 1000–1100 C.E., they built more than 600 structures (mostly residential but also for storage and ritual) into the cliff faces of the Four Corners region of the United States (the southwestern corner of Colorado, northwestern corner of New Mexico, northeastern corner of Arizona, and southeastern corner of Utah). The dwellings depicted here are located in what is today southwestern Colorado in the national park known as Mesa Verde (“verde” is Spanish for green and “mesa” literally means table in Spanish but here refers to the flat-topped mountains common in the southwest).

Ladder to Balcony House, Mesa Verde National Park (photo: Ken Lund, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The most famous residential sites date to the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. The Ancestral Puebloans accessed these dwellings with retractable ladders, and if you are sure footed and not afraid of heights, you can still visit some of these sites in the same way today.

To access Mesa Verde National Park, you drive up to the plateau along a winding road. People come from around the world to marvel at the natural beauty of the area as well as the archaeological remains, making it a popular tourist destination.

The twelfth- and thirteenth-century structures made of stone, mortar, and plaster remain the most intact. We often see traces of the people who constructed these buildings, such as hand or fingerprints in many of the mortar and plaster walls.

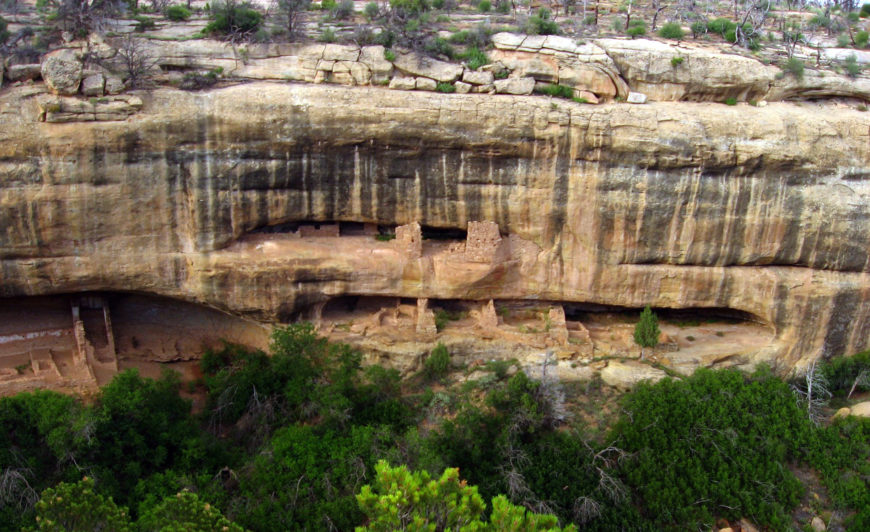

View of a canyon, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado (photo: FancyLady, CC BY-ND 2.0)

Ancestral Puebloans occupied the Mesa Verde region from about 450 C.E. to 1300 C.E. The inhabited region encompassed a far larger geographic area than is defined now by the national park, and included other residential sites like Hovenweep National Monument and Yellow Jacket Pueblo. Not everyone lived in cliff dwellings. Yellow Jacket Pueblo was also much larger than any site at Mesa Verde. It had 600–1200 rooms, and 700 people likely lived there (see link below). In contrast, only about 125 people lived in Cliff Palace (largest of the Mesa Verde sites), but the cliff dwellings are certainly among the best-preserved buildings from this time.

Cliff Palace, Ancestral Puebloan, 450–1300 C.E., sandstone, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Cliff palace

The largest of all the cliff dwellings, Cliff Palace, has about 150 rooms and more than twenty circular rooms. Due to its location, it was well protected from the elements. The buildings ranged from one to four stories, and some hit the natural stone “ceiling.” To build these structures, people used stone and mud mortar, along with wooden beams adapted to the natural clefts in the cliff face. This building technique was a shift from earlier structures in the Mesa Verde area, which, prior to 1000 C.E., had been made primarily of adobe (bricks made of clay, sand and straw or sticks). These stone and mortar buildings, along with the decorative elements and objects found inside them, provide important insights into the lives of the Ancestral Puebloan people during the thirteenth century.

View of Cliff Palace structures, Mesa Verde (photo: steeleman204, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

At sites like Cliff Palace, families lived in architectural units, organized around kivas (circular, subterranean rooms). A kiva typically had a wood-beamed roof held up by six engaged support columns made of masonry above a shelf-like banquette. Other typical features of a kiva include a firepit (or hearth), a ventilation shaft, a deflector (a low wall designed to prevent air drawn from the ventilation shaft from reaching the fire directly), and a sipapu, a small hole in the floor that is ceremonial in purpose. They developed from the pithouse, also a circular, subterranean room used as a living space.

Kiva without a roof, Cliff Palace, Mesa Verde National Park (photo: Adam Lederer, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Kivas continue to be used for ceremonies today by Puebloan peoples though not those within Mesa Verde National Park. In the past, these circular spaces were likely both ceremonial and residential. If you visit Cliff Palace, you will see the kivas without their roofs (see above), but in the past they would have been covered, and the space around them would have functioned as a small plaza.

Connected rooms fanned out around these plazas, creating a housing unit. One room, typically facing onto the plaza, contained a hearth. Family members most likely gathered here. Other rooms located off the hearth were most likely storage rooms, with just enough of an opening to squeeze your arm through a hole to grab anything you might need. Cliff Palace also features some unusual structures, including a circular tower. Archaeologists are still uncertain as to the exact use of the tower.

Kiva at Spruce Tree House, Mesa Verde National Park (photo: Doug Kerr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Painted murals

The builders of these structures plastered and painted murals, although what remains today is fairly fragmentary. Some murals display geometric designs, while other murals represent animals and plants.

For example, Mural 30, on the third floor of a rectangular “tower” (more accurately a room block) at Cliff Palace, is painted red against a white wall. The mural includes geometric shapes that are thought to portray the landscape. It is similar to murals inside of other cliff dwellings including Spruce Tree House and Balcony House. Scholars have suggested that the red band at the bottom symbolizes the earth while the lighter portion of the wall symbolizes the sky. The top of the red band, then, forms a kind of horizon line that separates the two. We recognize what look like triangular peaks, perhaps mountains on the horizon line. The rectangular element in the sky might relate to clouds, rain or to the sun and moon. The dotted lines might represent cracks in the earth.

The creators of the murals used paint produced from clay, organic materials, and minerals. For instance, the red color came from hematite (a red ocher). Blue pigment could be turquoise or azurite, while black was often derived from charcoal. Along with the complex architecture and mural painting, the Ancestral Puebloan peoples produced black-on-white ceramics and turquoise and shell jewelry (goods were imported from afar including shell and other types of pottery). Many of these high-quality objects and their materials demonstrate the close relationship these people had to the landscape. Notice, for example, how the geometric designs on the mugs above appear similar to those in Mural 30 at Cliff Palace.

Why build here?

From 500–1300 C.E., Ancestral Puebloans who lived at Mesa Verde were sedentary farmers and cultivated beans, squash, and corn. Corn originally came from what is today Mexico at some point during the first millennium of the Common Era. Originally most farmers lived near their crops, but this shifted in the late 1100s when people began to live near sources of water, and often had to walk longer distances to their crops.

New Fire House, Mesa Verde National Park (photo: Ken Lund, CC BY-SA 2.0)

So why move up to the cliff alcoves at all, away from water and crops? Did the cliffs provide protection from invaders? Were they defensive or were there other issues at play? Did the rock ledges have a ceremonial or spiritual significance? They certainly provide shade and protection from snow. Ultimately, we are left only with educated guesses—the exact reasons for building the cliff dwellings remain unknown to us.

Why were the cliffs abandoned?

The cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde were abandoned around 1300 C.E. After all the time and effort it took to build these beautiful dwellings, why did people leave the area? Cliff Palace was built in the twelfth century, why was it abandoned less than a hundred years later? These questions have not been answered conclusively, though it is likely that the migration from this area was due to either drought, lack of resources, violence or some combination of these. We know, for instance, that droughts occurred from 1276 to 1299. These dry periods likely caused a shortage of food and may have resulted in confrontations as resources became more scarce. The cliff dwellings remain, though, as compelling examples of how the Ancestral Puebloans literally carved their existence into the rocky landscape of today’s southwestern United States.

Go deeper

Yellow Jacket Pueblo reconstruction

Janet Catherine Berlo and Ruth B. Phillips, Native North American Art, 2 ed. Oxford History of Art series (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

Elizabeth A. Newsome and Kelley Hays-Gilpin, “Spectatorship and Performance in Mural Painting, AD 1250–1500,” Religious Transformation in the Late Pre-Hispanic Pueblo World, eds. Donna Glowacki and Scott Van Keuren, Amerind Studies in Archaeology (Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 2011).

David Grant Noble, ed., The Mesa Verde World: Explorations in Ancestral Pueblo Archaeology (Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press, 2006).

David W. Penney, North American Indian Art (London: Thames and Hudson, 2004).

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”Mesa Verde,”]