Thomas Hovenden’s The Last Moments of John Brown (c. 1884) will be useful in the study of:

- American and national identity

- Migration and settlement

- American and regional cultures

- The history of slavery in America

- The history of abolitionism in America

- The Civil War

- History of activism in the United States

- Race and national identity

- Politically-engaged art

By the end of this lesson, students should be able to:

- Discuss The Last Moments of John Brown as a primary document that links to its specific historical context during the nineteenth century

- Identify the social and political factors that led to the creation of this painting

- Discuss the story of John Brown and its relationship to how he is depicted in this painting

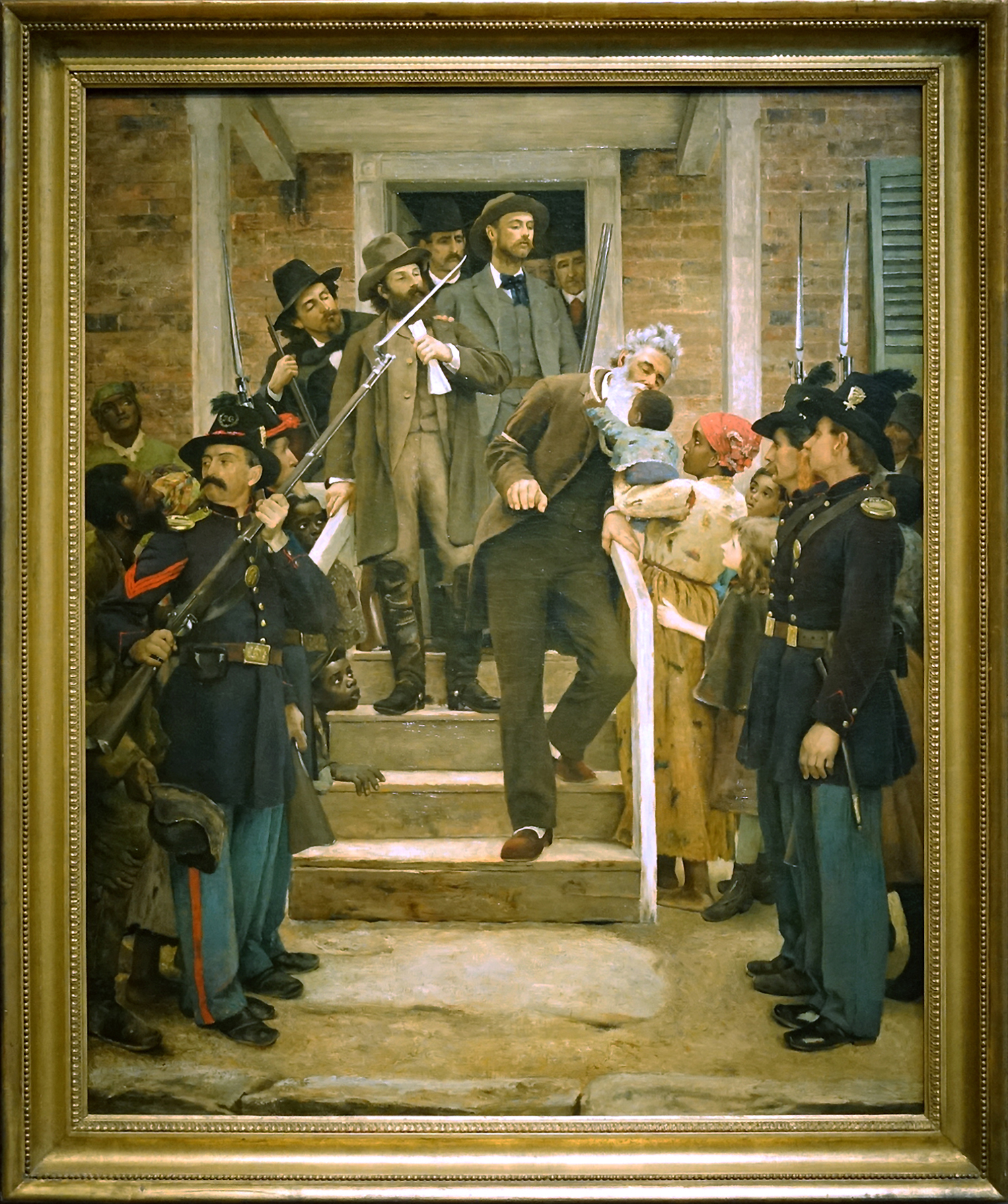

Thomas Hovenden, The Last Moments of John Brown, c. 1884, oil on canvas, 117.2 x 96.8 cm (de Young Museum, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

1. Look closely at the painting

Look closely at The Last Moments of John Brown (zoomable images, also available for download for teaching)

Questions to ask:

- Describe the painting. What stands out to you?

- What details in the painting might be important?

- What mood would you associate with this painting?

2. Watch the video

The video “Martyr or murderer? The Last Moments of John Brown” is only six minutes long. Ideally, the video should provide an active rather than a passive classroom experience. Please feel free to stop the video to respond to student questions, to underscore or develop issues, to define vocabulary, or to look closely at parts of the painting that are being discussed. Key points, a self-diagnostic quiz, and high resolution photographs with details of The Last Moments of John Brown are provided to support the video.

3. Read about the painting and its historical context

Abolition and action

The abolitionist John Brown led a raid on the federal armory at Harpers Ferry (in what is now West Virginia) in 1859. This was the last of several actions in which he used violence as a means to try to end slavery (which was itself filled with violence). He intended to redistribute the weapons stored in the armory to slaves and incite a rebellion that would lead to the end of slavery. Within two months of the raid and his arrest, Brown was tried, sentenced, and executed. The violent actions of John Brown to end slavery were controversial at the time. The debate surrounding the morality of the raid polarized American politics. It forced people to choose sides, and hardened opinions about slavery. It is believed to have contributed directly to the secession of southern states in 1860-61, but even some abolitionists were concerned by Brown’s violent methods.

Brown was a white man who had taken enormous risk to free enslaved African Americans. Even after his execution, Frederick Douglass referred to him as “Captain Brown,” and Harriet Tubman had tried to find volunteers to support the raid on Harpers Ferry. During the Civil War, John Brown became a hero to Union soldiers and the subject of a popular marching song. By World War I, this had changed, and today his place in history is controversial and complex.

Remembering John Brown

Painted 25 years after the raid at Harpers Ferry and Brown’s execution, Thomas Hovenden’s image is clearly sympathetic with John Brown. He depicts Brown on his way to his execution: his arms are bound, a noose is visible around his neck, and he is heavily guarded by armed men, yet he pauses to tenderly kiss a young child (a story that circulated in the press but was never confirmed). The young white girl near the bottom right, holding on to the African American woman’s skirts (the African American woman is probably meant to be her nanny), seems to look upon Brown as if she understands his importance — she is an embodiment of innocence and morality.

Hovenden also used religious references to elevate John Brown to the status of a martyr, depicting him with a long white beard like Moses and creating a subtle crucifix behind him. The soldiers’ bayonets imply latent violence, and echo representations of Christ presented to the people, surrounded by Roman soldiers. The position of the viewer also poses some questions to us — are we jailers? Are we part of the crowd? Are we sympathetic supporters? Are we part of the militia ready to escort him to the gallows? Hovenden has parted the crowd for us and given us privileged access to a moment in history.

4. Discussion question

- How do you respond to the speakers’ question about whether John Brown should be seen as a martyr or a terrorist? What reasons or historical examples inform your answer?

- Does this painting tell us more about American society and culture in 1859, or in 1884? Why?

5. Research questions

- Compare the lyrics of “John Brown’s Body” to those of “Old John Brown: A Song for Every Southern Man” (trigger warning: strong racist language). From these popular songs, how can we map out the political and economic issues that underlay the Civil War? How can we relate them to the way Hovenden designed his painting?

- Find two or three other depictions of John Brown in art (such as this one), and compare them to Thomas Hovenden’s The Last Moments of John Brown. How are they similar? How are they different? Is their attitude towards John Brown and his actions clear? Why or why not?

6. Bibliography

See this work at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Read how Abraham Lincoln addressed the raid in his 1860 speech at the Cooper Institute

Learn more about the friendship between John Brown and Frederick Douglass

Use primary sources to learn about the raid on Harpers Ferry

Read an essay on John Brown’s complicated place in American history

Read a letter written by John Brown and Frederick Douglass to Brown’s family

Read a review of two different exhibitions dealing with Harpers Ferry and its legacy

Read the lyrics and the history of the song “John Brown’s Body”

Listen to Pete Seeger sing “John Brown’s Body”

Watch a short talk by a historian on John Brown and the Raid on Harpers Ferry

Bruce A. Lesh, Interpreting John Brown: Infusing Historical Thinking into the Classroom, OAH Magazine of History, Volume 25, Issue 2, April 2011, Pages 46–50, https://doi.org/10.1093/oahmag/oar003