Aspiration at the 1936 Texas Centennial Exposition

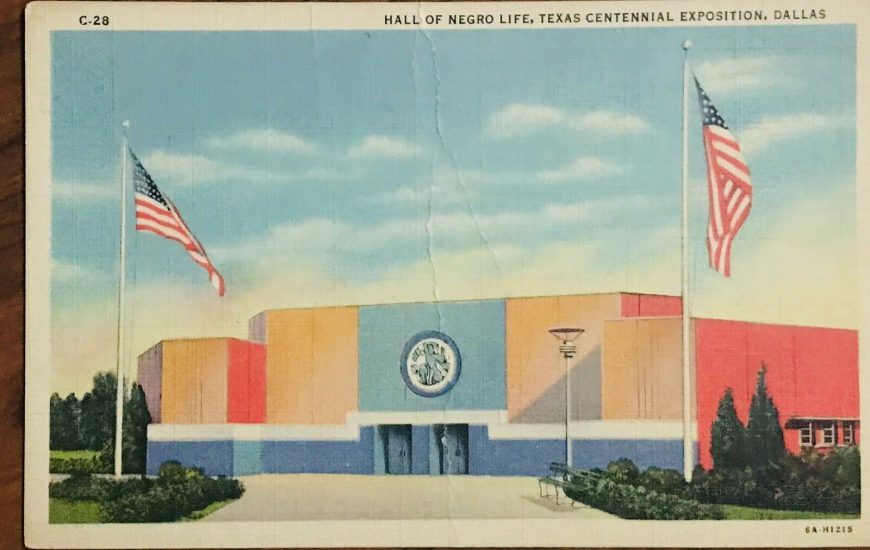

Aaron Douglas’s painting Aspiration, today in the de Young Museum in San Francisco, was one of four paintings created for the “Hall of Negro Life” at the 1936 Texas Centennial Exposition; only two of the paintings survive.

The subjects of the four paintings were:

1. Estevanico (one of the first native Africans to reach the present-day continental United States) [now lost]

2. The “Negro’s Gift to America” [now lost]

3. Into Bondage (National Gallery of Art)

4. Aspiration (de Young Museum, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco)

On the wall below Douglas’s paintings were painted the names of great African Americans “who distinguished themselves because of their peculiar contribution to the various phases of Negro progress and history in America.” (Jesse O. Thomas, Negro participation in the Texas centennial exposition (Boston: Christopher Pub. House, 1938))

Black organizers of the Hall of Negro Life sensed that whiteness defined itself in terms of binary opposition. If whiteness equaled progress, blackness must mean stasis. To portray blacks as a people who had progressed since slavery would directly undermine this view, even if this historical narrative implied that African Americans needed white tutors to achieve civilization. Visitors were hammered by the theme of progress as they entered the hall. At the front door, visitors encountered a sculptured plaster model of a black man “with broken chains from slavery, ignorance, and superstitions falling from his wrists.” A series of murals along the walls of the lobby by the artist Aaron Douglas of New York became the exhibit’s most eye catching and subversive feature. One mural, the ‘Negro’s Gift to America,’ portrayed blacks as builders of the country, contributing to music, art, and religion to American culture. A woman with a baby in her outstretched arms in the center of the painting symbolized ‘a plea for equal recognition…the child is a sort of banner, a pledge of Negro determination to carry on . . . in [a] struggle toward truth and light.’

Nevertheless the Hall of Negro Life proved too dangerous to survive. When officials announced that the centennial Exposition would continue in 1937 as the Greater Texas and Pan American Exposition, the hall was demolished, the only original permanent structure immediately destroyed.

Michael Phillips, White Metropolis: Race, Ethnicity, and Religion in Dallas, 1841-2001 (University of Texas Press, Jan 2, 2006), pp. 60-61.

Aaron Douglas, Aspiration, 1936 will be useful for the study of:

- The”New Negro”

- The Harlem Renaissance

- The continuing struggle for civil rights for African Americans

- The history of Texas

By the end of this lesson, students should be able to:

- Discuss Aaron Douglas’s Aspiration as a primary document that links to the specific historical context of continuing discrimination and the struggle for civil rights in the period between the World Wars

- Understand the “New Negro” and attempts by African Americans in this period to construct a narrative of the past in order to envision a better future

- Discuss the power of public art even in the context of a temporary exposition

- Apply the tools of visual analysis to support interpretation of the artwork

1. Look closely at the painting

Look closely at Aaron Douglas’s Aspiration (zoomable images, available for download for teaching)

Questions to ask:

Describe the three figures on the plinth. How would you describe our view of them in relation to the city in the upper corner?

The artist used a limited palette of colors – how would you describe them?

How do the various elements of the painting (the figures, shapes, and colors) suggest the meaning of the title, Aspiration (the hope of achieving something)?

2. Watch the video

The video “A beacon of hope, Aaron Douglas’s Aspiration” is less than 8 minutes in length. Ideally, the video should provide an active rather than a passive classroom experience. Please feel free to stop the video to respond to student questions, to underscore or develop issues, to define vocabulary, or to look closely at parts of the painting that are being discussed. Key points, a self-diagnostic quiz, and high resolution photographs with details of the work are provided to support the video.

3. Read about the painting and its historical context

Douglas translated jazz rhythm and improvisation into visual terms: concentric circles suggest sound emanating from raised instruments, syncopated by the intercepting silhouetted figures. In his speech at the First American Artists’ Congress in 1936, Douglas made his case for why black artists should look to vernacular traditions such as jazz and dance rather than to visual traditions rooted in Europe. The task of the black artist was to give ‘creative expression to a traditionless people….[he] is essentially a product of the masses and can never take a position above or beyond their level.’ Jazz was a New World art form, its potential to liberate expressed in the face of an oppressive history.

—Angela L. Miller, Janet Catherine Berlo, Bryan J. Wolf, and Jennifer L. Roberts, American Encounters: Art, History, and Cultural Identity (Washington University Libraries, 2018), p. 529 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

“like a spiritual emancipation”: The Harlem Renaissance

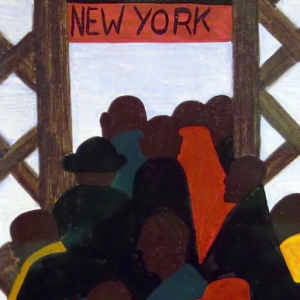

Detail. Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series, 1940-41, 60 panels, tempera on hardboard (even numbers at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, odd numbers at the Phillips Collection, Washington D.C.)

Just as cultural limits loosened across the nation, the 1920s represented a period of serious self-reflection among African Americans, most especially those in northern ghettos. New York City was a popular destination of American blacks during the Great Migration. The city’s black population grew 257 percent, from 91,709 in 1910 to 327,706 by 1930 (the white population grew only 20 percent).[1] Moreover, by 1930, some 98,620 foreign-born blacks had migrated to the United States. Nearly half made their home in Manhattan’s Harlem district.[2]

Harlem originally lay between Fifth Avenue and Eighth Avenue and 130th Street to 145th Street. By 1930, the district had expanded to 155th Street and was home to 164,000 people, mostly African Americans. Continuous relocation to “the greatest Negro City in the world” exacerbated problems with crime, health, housing, and unemployment. Nevertheless, it brought together a mass of black people energized by race pride, military service in World War I, the urban environment, and, for many, ideas of Pan-Africanism or Garveyism. James Weldon Johnson called Harlem “the Culture Capital.”[3] The area’s cultural ferment produced the Harlem Renaissance and fostered what was then termed the New Negro Movement.

Alain Locke did not coin the term New Negro, but he did much to popularize it. In the 1925 book The New Negro, Locke proclaimed that the generation of subservience was no more—“we are achieving something like a spiritual emancipation.” Bringing together writings by men and women, young and old, black and white, Locke produced an anthology that was of African Americans, rather than only about them. The book joined many others. Popular Harlem Renaissance writers published some twenty-six novels, ten volumes of poetry, and countless short stories between 1922 and 1935.[4] Alongside the well-known Langston Hughes and Claude McKay, female writers like Jessie Redmon Fauset and Zora Neale Hurston published nearly one third of these novels. While themes varied, the literature frequently explored and countered pervading stereotypes and forms of American racial prejudice.

- Mark R. Schneider, “We Return Fighting”: The Civil Rights Movement in the Jazz Age (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2002), p. 21.

- Philip Kasinitz, Caribbean New York: Black Immigrants and the Politics of Race (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1992), p. 25.

- James Weldon Johnson, “Harlem: The Culture Capital,” in Alain Locke, The New Negro: An Interpretation (New York: Albert and Charles Boni, 1925), p. 301.

- Joan Marter, ed., The Grove Encyclopedia of American Art, Volume 1 (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2011), p. 448.

— “The New Era,” American Yawp (Stanford University Press, CC BY-SA 4.0)

4. Discussion question

Negro life is not only establishing new contacts and founding new centers, it is finding a new soul. There is a fresh spiritual and cultural focusing. We have, as the heralding sign, an unusual outburst of creative expression. There is renewed race-spirit that consciously and proudly sets itself apart.— Alain Locke

African American culture saw a remarkable Renaissance in the 1920s and 30s, often accompanied by a passionate optimism about the future of African Americans in the United States. This optimism was apparent at the Hall of Negro Life at the Texas Centennial of 1936, and in Douglas’s paintings for its entrance. If you could talk to someone from that period, knowing what we know today about all that has happened since the 1930s, what would you tell them?

5. Research question

Art historian Renee Ater has written that Douglas “understood the present and the future as being tied to the past.” Why did Douglas and others feel it was so important to write a past in order to move forward into the future? How does Douglas tie the past to the future in the painting Aspiration and what do you think Douglas is saying about future of African Americans going forward?

6. Bibliography

This painting at the de Young Museum

Aaron Douglas, Into Bondage, from The National Gallery of Art

Hall of Negro Life, Texas State Historical Association

Renée Ater, “Creating a ‘Usable Past’ and a ‘Future Perfect Society’: Aaron Douglas’s Murals for the 1936 Texas Centennial Exposition,”in Aaron Douglas: African American Modernist, ed. Susan Earle (New Haven and London: Yale University Press in association with the University of Kansas Spencer Museum of Art, 2007), pp. 95-113.

Jesse O. Thomas, Negro participation in the Texas Centennial Exposition (Boston, MA: Christopher Publishing House, 1938).