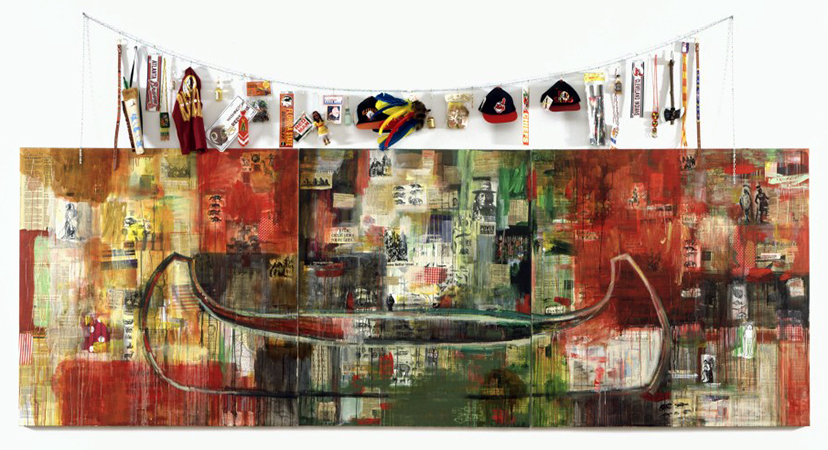

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Trade (Gifts for Trading Land with White People), 1992, oil paint and mixed media, collage, objects, canvas, 152.4 x 431.8 cm (Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Virginia) © Jaune Quick-to-See Smith

A Non-Celebration

As a response to the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ arrival in North America in 1992, the artist Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, from the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Indian Nation, created a large mixed-media canvas called Trade (Gifts for Trading Land with White People). Trade, part of the series “The Quincentenary Non-Celebration,” illustrates historical and contemporary inequities between Native Americans and the United States government.

Trade references the role of trade goods in allegorical stories like the acquisition of the island of Manhattan by Dutch colonists in 1626 from unnamed Native Americans in exchange for goods worth 60 guilders or $24.00. Though more apocryphal than true, this story has become part of American lore, suggesting that Native Americans had been lured off their lands by inexpensive trade goods. The fundamental misunderstanding between the Native and non-Native worlds—especially the notion of private ownership of land—underlies Trade. Smith stated that if Trade could speak, it might say: “Why won’t you consider trading the land we handed over to you for these silly trinkets that so honor us? Sound like a bad deal? Well, that’s the deal you gave us.”1

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, canoe (detail), Trade (Gifts for Trading Land with White People), 1992, oil paint and mixed media, collage, objects, canvas, 152.4 x 431.8 cm (Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Virginia) © Jaune Quick-to-See Smith

For Trade, Smith layered images, paint, and objects on the surface of the canvas, suggesting layers of history and complexity. Divided into three large panels, the triptych (three part) arrangement is reminiscent of a medieval altarpiece. Smith covered the canvas in collage, with newspaper articles about Native life cut out from her tribal paper Char-Koosta, photos, comics, tobacco and gum wrappers, fruit carton labels, ads, and pages from comic books, all of which feature stereotypical images of Native Americans. She mixed the collaged text with photos of deer, buffalo, and Native men in historic dress holding pipes with feathers in their hair, and an image of Ken Plenty Horses—a character from one of Smith’s earlier pieces, the Paper Dolls for a Post Columbian World with Ensembles Contributed by US Government from 1991-92.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, toys and souvenirs (detail), Trade (Gifts for Trading Land with White People), 1992, oil paint and mixed media, collage, objects, canvas, 152.4 x 431.8 cm (Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Virginia) © Jaune Quick-to-See Smith

She applied blocks of white, yellow, green, and especially red paint over the layer of collaged materials. The color red had multiple meanings for Smith, referring to her Native heritage as well as to blood, warfare, anger, and sacrifice. With the emphasis on prominent brushstrokes and the dripping blocks of paint, Smith cited the Abstract Expressionist movement from the 1940s and 50s with raw brushstrokes describing deep emotions and social chaos. For a final layer, she painted the outline of an almost life-sized canoe. Canoes were used by Native Americans as well as non-Native explorers and traders in the eighteenth, nineteenth and early twentieth century to travel along the waterways of North America. The canoe suggests the possibility of trade and cultural connections—though this empty canoe is stuck, unable to move.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, toys and souvenirs (detail), Trade (Gifts for Trading Land with White People), 1992, oil paint and mixed media, collage, objects, canvas, 152.4 x 431.8 cm (Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Virginia) © Jaune Quick-to-See Smith

Above the canvas, Smith strung a clothesline from which she dangled a variety of Native-themed toys and souvenirs, especially from sports teams with Native American mascots. The items include toy tomahawks, a child’s headdress with brightly dyed feathers, Red Man chewing tobacco, a Washington Redskins cap and license plate, a Florida State Seminoles bumper sticker, a Cleveland Indian pennant and cap, an Atlanta Braves license plate, a beaded belt, a toy quiver with an arrow, and a plastic Indian doll. Smith offers these cheap goods in exchange for the lands that were lost, reversing the historic sale of land for trinkets. These items also serve as reminders of how Native life has been commodified, turning Native cultural objects into cheap items sold without a true understanding of what the original meanings were.

The Artist

The artist was born on January 15, 1940, at the St. Ignatius Jesuit Missionary on the Reservation of the Flathead Nation. Raised by her father, a rodeo rider and horse trader, Smith was one of eleven children. Her first name comes from the French word for “yellow” (jaune), a reminder of her French-Cree ancestors. Her middle name “Quick-to-See” was not a reference to her eyesight but was given by her Shoshone grandmother as a sign of her ability to grasp things readily. From an early age Smith wanted to be an artist; as a child, she had herself photographed while dressed as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Though her father was not literate, education was important to Smith.

National Bison Range (near St. Ignatius, Flathead Reservation) (photo: Jaix Chaix, Check All Home Inspection Corp., CC BY-SA 2.0)

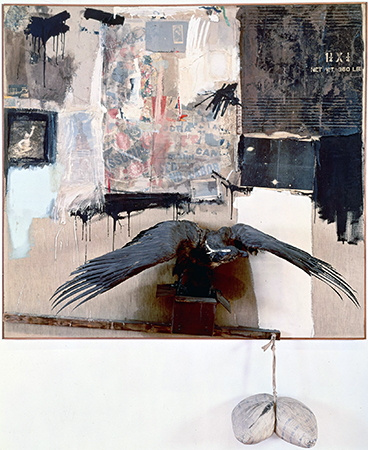

She received a bachelor of arts from Framingham State College in Massachusetts in 1976 in art education rather than in studio art because her instructors told her that no woman could have a career as an artist, though they acknowledged that she was more skilled than the men in her class. In 1980 she received a master of fine arts from the University of New Mexico. She was inspired by both Native and non-Native sources, including petroglyphs, Plains leger art, Diné saddle blankets, early Charles Russell prints of western landscapes, and paintings by twentieth-century artists such as Paul Klee, Joan Miró, Willem DeKooning, Jasper Johns, and especially Kurt Schwitters and Robert Rauschenberg (see image below). Both Schwitters and Rauschenberg brought objects from the quotidian world into their work, such as tickets, cigarette wrappers, and string.

Robert Rauschenberg, Canyon, 1959, oil, pencil, paper, metal, photograph, fabric, wood, canvas, buttons, mirror, taxidermied eagle, cardboard, pillow, paint tube and other materials, 207.6 x 177.8 x 61 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York) © 2014 Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

In addition to her work as an artist, Smith has curated over thirty exhibitions to promote and highlight the art of other Native artists. She has also lectured extensively, been an artist-in-residence at numerous universities, and has taught art at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico the only four-year university dedicated to teaching Native youth across North America. In her years as an artist, Smith has received many honors, including an Eitelijorg Fellowship in 2007, a grant from the Joan Mitchell Foundation to create a comprehensive archive of her work, a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Women’s Caucus for the Arts, the College Art Association’s Committee on Women in the Arts award, the 2005 New Mexico Governor’s award for excellence in the arts, as well as four honorary doctorate degrees.

Smith’s art shares her view of the world, offering her personal perspective as an artist, a Native American, and a woman. Her work creates a dialogue between the art and its viewers and explores issues of Native identity as it is seen by both Native Americans and non-Natives. Trade (Gifts for Trading Land with White People) restates the standard narratives of the history of the United States, specifically the desire to expand beyond “sea to shining sea,” as encompassed in the ideology of Manifest Destiny (the belief in the destiny of Western expansion), and raises the issue of contemporary inequities that are rooted in colonial experience.

1. Arlene Hirschfelder, Artists and Craftspeople, American Indian Lives, New York: Facts On File, 1994, page 115.

Go deeper

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith at the Smithsonian American Art Museum

“Smith, Jaune Quick-to-See” in American Indian History Online

Lawrence Abbot, I Stand in the Center of the Good: Interviews with Contemporary Native American Artists, University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, 1994.

Carolyn Kastner, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: An American Modernist, University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque, 2013.

Melanie Herzog, “Building Bridges Across Canada: Jaune Quick-to-See Smith.” School Arts (October 1992): 31–34.

Tricia Hurst, “Crossing Bridges: Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Helen Hardin, Jean Bales.” Southwest Art, April 1981, 82–91.

Tricia Hurst, ”Jaune Quick-to-See Smith,” January 17–March 14, 1993. Norfolk, Virginia: Chrysler Museum, 1993.

Joni L. Murphy, “Beyond Sweetgrass: The Life and Art of Jaune Quick-To-See Smith.” Ph.D. dissertation. University of Kansas, 2008.