The present essay collection, Not Your Grandfather’s Art History: A BIPOC Reader, has a clear, if ambitious, goal: to challenge the normativity of whiteness within art history classrooms and scholarship. This normativity pervades virtually all aspects of the discipline, from the artists we teach, to the dominance of Europe as the touchstone of art historical inquiry; from the ranks of professors to the methodological approaches we teach. The collection seeks to grapple with each of these challenges in turn: finding new subjects for art historical study, promoting the scholarship of art historians of color, and reimagining the purview of art historical scholarship.

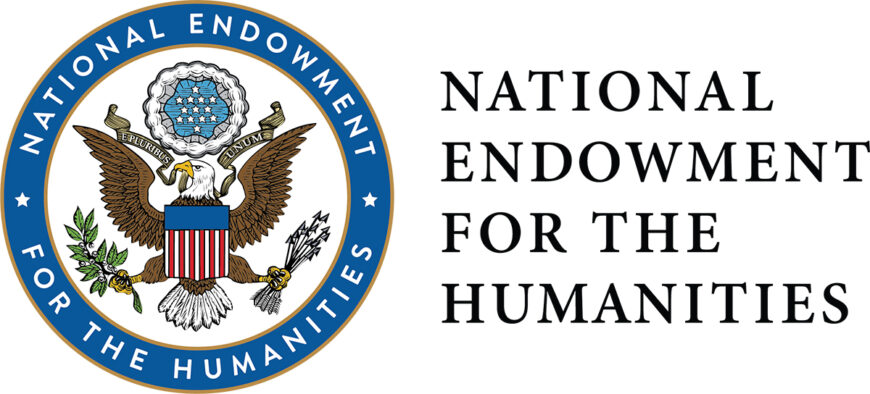

Left: philosophers (detail), Raphael, School of Athens, 1509–11, fresco (Stanza della Segnatura, Papal Palace, Vatican); right: Jacob Lawrence, In the North the Negro had better educational facilities, from the Migration series, 1940–41, casein tempera on hardboard, 30.5 x 45.7 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York)

But a larger question remains: How do we actively integrate these historical lessons into our classrooms, the site where most students will engage with art history for the first time? It is one thing to assign essays from this reader. It is quite another to get students to be receptive to the larger lessons they embody. We know that students come to class with a whole set of assumptions about our discipline, even if they have never taken an art history course. Thus, the vision of art history that forms the basis of this reader requires significant unlearning: rethinking the historical engines of history, upending whose visions and values that guide art historical inquiry, and even challenging what constitutes art. For many students, this unlearning will require acknowledging their own privilege. This can be a scary prospect and often elicits resistance. It is hard enough to get students to complete assigned readings. Asking them to commit to the reflective work necessary to challenge white supremacy in art history adds a whole other layer of difficulty.

We want our students to see themselves in art history, to relate to the discipline on a profound level and make a lifelong investment in the power of art. We want them to find something in the discipline that produces fascination, devotion, scorn, or any other response that will lead them to eventually reimagine art history in ways that we cannot yet imagine. But while students should not feel that art history excludes them, they should also understand the double bind of “representation” (the potential it holds for expression and oppression) if they are to truly understand how the structures of white supremacy in art history function. This is where pedagogy (thinking beyond questions of the cannon and addressing teaching practices and methods) is key.

In what follows, I build upon my experience teaching histories of Black art and anti-Black racism in North America to offer a few reflections for how to embark upon the pedagogical work made possible by this reader. I have taught community college, undergraduate, and graduate students at multiple public universities in both the United States and Canada. I have taught in classrooms where Black and Brown students are the majority and in classrooms where they are very much the minority. In every instance, I teach from the position of a non-Black, racialized, cis woman. All along the way, my teaching has been informed by generous conversations with brilliant colleagues and students. My hope is that the lessons I have learned from these experiences are useful to others who believe that building anti-racist pedagogy is central for building an anti-racist art history.

Marie Watt, Companion Species (Speech Bubble), 2019, reclaimed wool blankets, embroidery floss, and thread, 136 5/8 x 198 1/2 inches (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville; photo: Edward C. Robison III) © Marie Watt

Why art history

Most of the students who enroll in an art history course will not go on to have careers as art historians—whatever that might mean. Thus, it is incumbent upon us as educators to think about the larger import of our discipline, what it can offer students beyond the acquisition of specialized knowledge. The ability to critically understand the working of power through and beyond the visual is paramount. In art history, we teach students that works of art are not neutral, that they convey a set of meanings that speak to the values, conflicts, and changes that define the times in which they were made. If we deemphasize artists, dates, and discipline-specific terminology in our teaching, we can instead help students identify, analyze, and discuss the various forms of power (related to race, gender, class, sexual identity, etc.) that cohere in and produce the works that constitute the history of art. We should be explicit about this shift in perspective and its implications with our students, to help them understand that the changes we seek for the discipline are holistic and structural, rather than simply additive or subtractive.

Juan de Pareja, The Calling of Saint Matthew, 1661, oil on canvas, 225 x 325 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid)

What we talk about when we talk about white supremacy

If we define white supremacy only as identifying or “calling out” whiteness, we are missing the forest for the trees. White supremacy is an ideology. This means that it shapes virtually every aspect of everyday life. We need to ask not just what whiteness is, but what whiteness does, how it produces certain modes of thought, structures particular forms of relationality, and creates ways of living. White supremacy is also deeply imbricated in other forms of oppression. In this way, understanding white supremacy is not the examination of whiteness, or at least not exclusively. For example, it is impossible to discuss the violence of the transatlantic slave trade without also analyzing the development of capitalism as a world system. In this instance, an analysis of white supremacy would also entail an analysis of how capitalism incentivized racial violence and thus how racial and economic oppression are connected.

Getting students to “see” whiteness means elucidating the complex ways oppression operates, particularly across groups that white supremacy makes us believe are distinct or even opposed (Black, white; male, female; rich, poor; self, other, etc.). We should be showing students the various ways art historians might address these issues, i.e. facilitating a shift from a discussion of what we study (content) to a discussion of how we study it (method). We also need to teach students that whiteness, and indeed all racial identities, are not immutable or static categories. They each have their own histories, histories in which art plays a significant role. If we view the history of art history in this way, showing students how art does not just reflect but actively informs the production of race, then we teach them that the visual is never divorced from racial ideology. The goal is not to “add” another layer onto a pre-existing set of narratives but to produce a version of the discipline where the histories of race and visuality are unthinkable without one another.

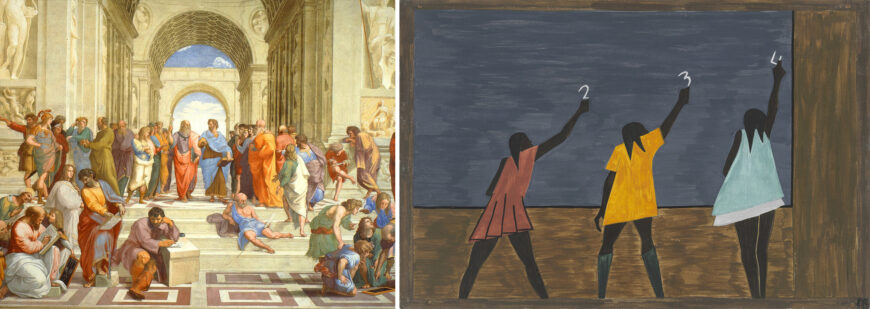

“The March of the Spaniards into Tenochtitlan,” Codex Azcatitlan, folio 23, c. 1530, 21 x 28 cm (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris)

Subjects/objects

The distinction between subject and object is central to art historical study. Art history is, primarily, the study of objects. We encourage students to look at and deeply engage with things that hold multiple meanings beyond the intention of their makers. But again, histories of racial oppression complicate the idea of what and indeed who constitutes an object. Enslaved people, women, colonial “subjects,” are just a few examples of historical actors that blur the boundary between subject and object and thus suggest that the ever-changing relationship between these two terms has always been a powerful engine of historical change that can raise a number of questions: What are the subjects of art history? Who gets to be a subject and who or what is an object? How do we discuss “agency” in art history (what constitutes it, where can it be located, how can it be measured)? Are we treating our students as subjects or objects in the classroom? These generative questions can propel an entire semester or even an entire year’s worth of teaching.

Showing our work

Tackling white supremacy in the classroom must go beyond the level of content. It must also address the very social forms that structure the classroom itself. In this way, challenging white supremacy through teaching also requires self-assessment on behalf of the instructor. Letting students into the thought process behind our teaching methods can be extremely useful. By telling students what choices we struggled with in choosing examples or readings, making them aware of how we are still working through a particularly difficult question, telling them that we want them to challenge our examples and assumptions (in the same productive and respectful ways that we raise these issues with them to begin with) we show students that we are learning along with and from them. We also convey to them that the enormity of these issues requires constant learning and relearning.

Knotted Carpet with human figures and Brahmi/Khotanese inscriptions, 5th–6th century C.E. (Shanpula Township, Khotan District, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China) (photo: Qi Xiaoshan)

Putting the students in art history

Art history, like the rest of the humanities, is facing increasingly frequent and prominent accusations of irrelevance. Those of us who teach and study art history know that these charges are short-sighted. As discussed above, the lessons of art history are deeply applicable in a world where vision is constantly being redirected across platforms, screens, and other sites of visual production. Nevertheless, persuading people to accept the importance of the discipline by insisting upon the discipline as it has been practiced historically is, in all likelihood, a losing battle. This is in large part precisely because these historical practices are, as this reader shows, so deeply invested in whiteness, masculinity, heteropatriarchy, and elitism. In other words, we should insist upon the power and relevance of the discipline by articulating new directions where it can grow. Elevating the opinions and experiences of students in these transformations holds immense potential in this regard. We should assure students that their personal opinions and experiences are welcomed in the classroom. But we should also find ways to weave those experiences into the very fabric of what art history is; conveying to students that they have the power to define how art history will be practiced in the future.

Conclusion

These reflections are not meant to be prescriptive. Each of us has to develop our own pedagogical strategies based on where, what, and how we teach. If this essay has a guiding spirit, it is that of collective action—sharing ideas, aspirations, and practices with the larger goal of cultivating collective force within and beyond our classroom. This is the very force we’ll need to undo the decades of systemic retrenchment that continues to reinscribe the power of whiteness within art history.

Additional resources

bell hooks, Teaching to Transgress (London: Routledge, 1994).

Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, translated by Myra Bergman Ramos (New York: Seabury Press, 1970).

Caitlin Meehye Beach, Sculpture at the Ends of Slavery (Oakland: University of California Press, 2022).

Huey Copeland, Bound to Appear: Art, Slavery, and the Site of Blackness in Multicultural America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013).

Lisa Lowe, The Intimacies of Four Continents (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015).

Nicholas Mirzeoff, White Sight: Visual Politics and Practices of Whiteness (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2023).