The Growing States

Essay by Dr. Bryan Zygmont

Emanuel Leute, Westward the Course of Empire Takes its Way, 1862, installed in the House Wing, west stairway of the U.S. Capital, stereochromy mural, 20’ x 30’ (Architect of the Capital)

If the United States of America was born during the final quarter of the eighteenth century, it became a toddler during the opening decades of the nineteenth century, and progressed to early adolescence by mid-century. And if toddlers begin to exert a wary independence from their parents, and if teenagers often grapple with ideas of identity—that is, determining the kind of person they wish to become—then it was during the first half of the nineteenth century that the United States initiated the transition from infancy to adulthood.

Three interrelated events framed this half century of American history. The first is westward expansion that changed the United States from a country isolated on the eastern seaboard to one spanning the entire continent. The second was the conflict with Great Britain during the War of 1812 and later, the Mexican-American War, both military skirmishes that reaffirmed the increasing presence of the United States on the world’s stage. The final issue is the continuation and expansion of slavery, a problem that had begun to tear the fabric of the country apart.

The Louisiana Purchase Treaty

Rhode Island—the last of the original colonies to ratify the United States Constitution—was officially admitted to the union on 29 May, 1790. Over the next thirteen years, four additional states—Vermont (1791), Kentucky (1792), Tennessee (1796), and Ohio (1803)—joined the United States, bringing the number of states to seventeen.

The date when Ohio was admitted—1 March—is particularly interesting. Less than two months later, on 30 April 1803, Robert R. Livingston (the American minister to France from 1801–04) and James Monroe (who had earlier served in that post from 1794–96) met with their French counterpart, François Barbé-Marbois, to sign the Louisiana Purchase Treaty.

The Louisiana Purchase states marked in white (image: David Levy, CC SA-BY 4.0)

The treaty was a pact that greatly increased the land holdings of the United States though at the expense of the numerous Native American nations already there. At the conclusion of the negotiations, Livingston is reported to have said, “We have lived long, but this is the noblest work of our whole lives…From this day the United States take their place among the first powers of the world.”

Indeed, with several strokes of a quill, Livingston and Monroe nearly doubled the recognized landmass of the United States. The final ledger suggests that the Louisiana Purchase added nearly 828,000 square miles at a cost of about $18.10 per square mile.

“Ocian in view! O! the joy”

Bronze statue by Pat Kennedy of Meriwether Lewis, William Clark and Clark’s dog, Seaman, dedicated in 2003, Saint Charles, Missouri (photo: Dr. David Goodrich, CC BY 2.0)

The landmass the United States purchased from France was truly colossal, and contains what is now South Dakota, Iowa, Nebraska, Kansas, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Arkansas, and parts of Texas, New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, North Dakota, Minnesota, and, of course, Louisiana.

Months after the treaty was signed, President Thomas Jefferson commissioned two men—Captain Meriwether Lewis and Second Lieutenant William Clark—to lead the Corps of Discovery in the exploration of this newly purchased land.

Lewis, Clark, and their intrepid colleagues departed Camp DuBois, located at the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers, on the afternoon of 14 May 1804. Over the next 18 months, the Lewis and Clark Expedition explored westwards, chronicling the waterways, flora, and fauna of this vast tract of land.

After arriving at the Pacific Ocean on 7 November (“Ocian in view! O! the joy,” Clark wrote in his journal), the expedition explored the nearby environs before eventually wintering at Fort Clatsop in Oregon. They departed eastward on 22 March 1806 and arrived in St. Louis on 23 September 1806.

Manifest destiny to overspread and possess

In this 8,000-mile round-trip adventure, the Lewis and Clark Expedition tapped into what would become the zeitgeist for much of the nineteenth century: the westward exploration and settling of the North American continent.

The expression that became synonymous with this progression was Manifest Destiny, a phrase first coined by John L. O’Sullivan, the publisher of the New York Morning News. On 27 December 1845, when discussing a boundary dispute between Great Britain and the United States over land in what is now the state of Oregon, O’Sullivan wrote, “And that claim is by the right of our manifest destiny to overspread and possess the whole of the continent which Providence has given us for the development of the great experiment of liberty and federated self-government entrusted to us.”

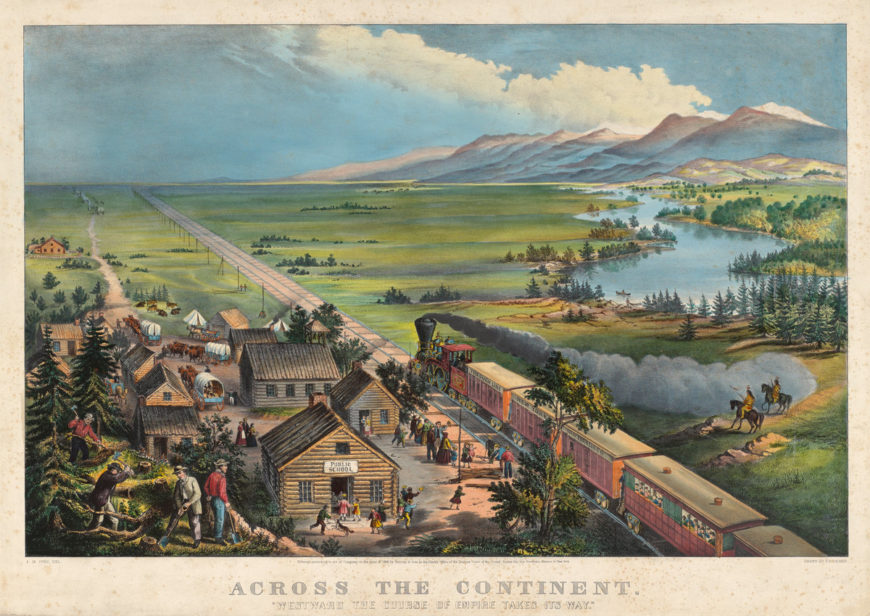

after Frances Flora Bond Palmer, Across the Continent: “Westward the Course of Empire Takes its Way,” 1868, hand-colored lithograph (National Gallery of Art, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 1985.64.160)

Although this remark dates from the end of 1845, O’Sullivan’s phrase—Manifest Destiny—succinctly captured an idea that had been a part of the American ethos of expansion for almost a half of a century: that the North American continent was there for the taking, and that it was the divinely mandated obligation of the United States to settle this land.

Free states, slave states, and sad compromise

With land acquired and subsequently explored, the federal government began to admit new states into the Union. Between 1812 and 1850, 14 states joined the United States, areas that ranged from Maine (1820) to California (1850). The admittance of Maine played a particularly pivotal role in the development of the history of the United States.

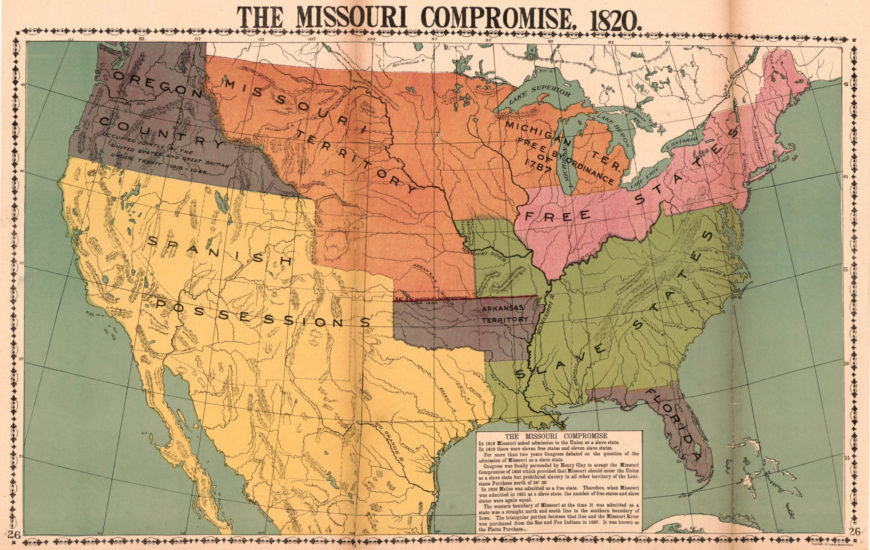

The Missouri Compromise of 1820 from McConnell’s Historical maps of the United States, 1919 (Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, public domain)

On 3 March 1820, the sixteenth congress of the United States passed the so-called Missouri Compromise, an act that prohibited slavery north of the 36°30′ parallel, excluding the state of Missouri, a state north of that designation. Maine was admitted as a free state less than two weeks later, and in order to keep the ratio of slave states to free states in balance, Missouri was admitted as a slave-holding state on 10 August 1821.

In the Missouri Compromise lay the foundation of the continuation of slavery in the United States of America, and the genesis of the American Civil War that would tear the country apart between 1861 and 1865. As states were added to the union in the decades that followed this important act of legislation, it further reinforced a geographical divide between the free states in the north and the slaveholding states to the south.

It also all but guaranteed a political stalemate as it pertained to the abolishing of slavery, for when a free state was admitted to the union, another slave holding state was added, too. Arkansas joined as a slave state in 1836; Michigan was admitted as a free state less than eight months later. Florida and Texas were admitted as a slave states in March and December 1845; Iowa and Wisconsin joined as free states in 1846 and 1848. The divide—both in numbers and in geography—that existed at the opening of the nineteenth century had only deepened and expanded fifty years later.

The Second War for American Independence

The opening years of the nineteenth century were turbulent and exciting for the new nation. The first decade was not yet over when the Louisiana Purchase essentially doubled the landmass of the United States. In doing so, the United States quite suddenly became a world power in mass if not yet in might. Immediately following the signing of the Treaty of the Louisiana Purchase, Napoleon is noted to have said, “The accession of territory affirms forever the power of the United States and I have given England a maritime rival who will sooner or later will humble her pride.” Napoleon was correct.

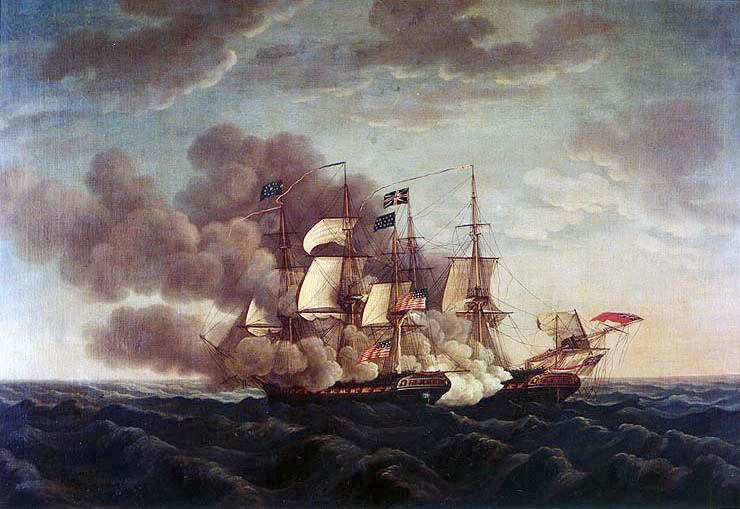

Michel Felice Corne, Action between USS Constitution and HMS Guerriere, 19 August 1812, c. 19th century, oil on canvas, 32″ x 48″ (U.S. Naval Academy Museum)

The American victory in the War of 1812, a conflict sometimes called The Second War for American Independence, provided the young country with a great sense of confidence in relation to the world at large. So much so that that in 1823, President James Monroe created a policy that in time has come to bear his name, the Monroe Doctrine. In it, the United States created a policy that all but barred European countries from intervening in North America.

In essence, the Monroe Doctrine suggested what O’Sullivan wrote two decades later: the land between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans belonged to the United States, and it was our obligation—and no one else’s—to settle it. At the conclusion of the Mexican-American War, the United States took possession of what is now Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California.

A new (old) world

It can be said that the acquisition of territory and the prohibition of European influence upon that land was the United States growing up and away from its old-world parents. But wrestling with the profound issues of slavery was the true adolescence of the United States, the moment in its history when it collectively decided what kind of country it wished to become in the full maturation of its adulthood.

General Scott’s entrance into Mexico in the Mexican-American War , 1851, hand-colored lithograph published after Carl Nebel ( public domain )

Nothing had yet been determined at midcentury, but the breeze of discontent that had whispered through the wilderness at the beginning of the century had become a tornado of unrest fifty years later. In moving towards adulthood in the second half of this turbulent century, it would take the Civil War for the United States to (attempt to) live up to the lines Thomas Jefferson wrote in the second paragraph of the Declaration of Independence: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. ”

In this, progress—slow though it may have been—was being made.