I want to make paintings…I want to make sculptures that are honest, that wrestle with the struggles of our past but speak to the diversity and the advances of our present.

—Titus Kaphar

You asked us to throw off the hunter and warrior state: We did so—you asked us to form a republican government: We did so. Adopting your own as our model. You asked us to cultivate the earth, and learn the mechanic arts. We did so. You asked us to learn to read. We did so. You asked us to cast away our idols and worship your god. We did so. Now you demand we cede to you our lands. That we will not do.

— John Ridge, 1831 (as quoted in Scott Malcomson, One Drop of Blood: The American Misadventure of Race (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000)

Titus Kaphar’s The Cost of Removal (2017) will be useful for the study of:

- The presidency of Andrew Jackson

- The Indian Removal Act

- The Trail of Tears

- The presidency of Donald Trump, which recalls, in its populism, the the presidency of Andrew Jackson and which created a backlash and prompted a critical look at the history of the United States in relation to women, minorities, immigrants

By the end of this lesson, students should be able to:

- Discuss Titus Kaphar’s The Cost of Removal as a primary document that links to the specific historical context of the United States during the presidency of Donald Trump, and a retrospective look at the presidency of Andrew Jackson

- Look at museums critically—as places that make decisions about who to leave out and who to include on their walls

- Understand the history of American portraiture as one that, for the most part, celebrates the dominant white culture

- Understand the Indian Removal Act, as well as the motivations of white settlers and the attempts to resist removal by Native Americans

1. Look closely at the painting

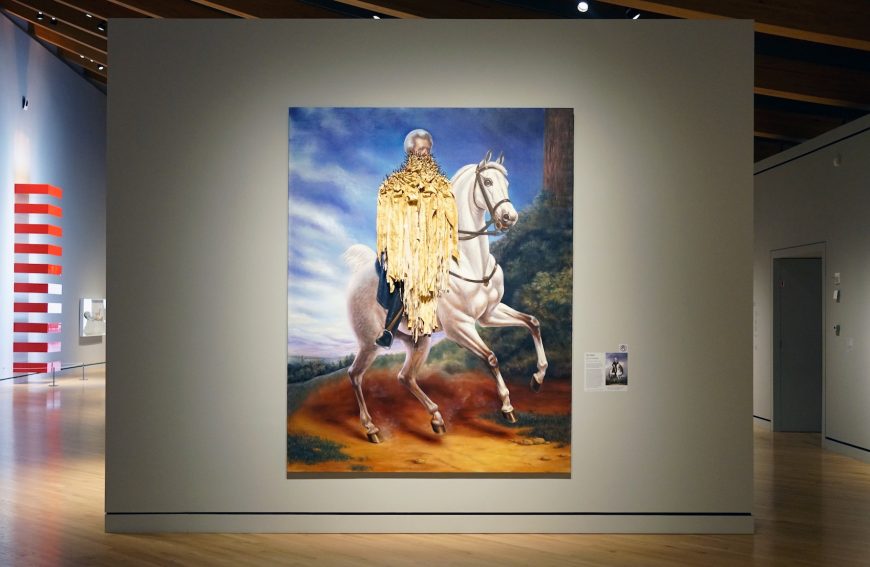

Titus Kaphar, The Cost of Removal, oil, canvas, and rusted nails on canvas, 274.3 × 213.4 × 3.8 cm (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art)

Look closely at The Cost of Removal by Titus Kaphar (downloadable image for teaching)

Questions to ask:

- Describe the figure. What parts of him can you see and what can’t you see?

- How do the nails and strips of canvas contrast with the traditional elements of an equestrian portrait?

- Can you get a sense of the scale of the painting? How would a viewer physically relate to the image of Jackson astride the horse?

- How closely does Kaphar’s painting match the portrait of Jackson by Ralph Earl that the artist used for inspiration? How is it similar? How is it different?

- Can you read any of the text on the strips of canvas? Does it matter whether or not you can read them?

2. Watch the video

The video on Kaphar’s The Cost of Removal is about 5 minutes in length. Ideally, the video should provide an active rather than a passive classroom experience. Please feel free to stop the video to respond to student questions, to underscore or develop issues, to define vocabulary, or to look closely at parts of the painting that are being discussed. Key points, a self-diagnostic quiz, and high resolution photographs with details of the work are provided to support the video.

3. Read about the painting and its historical context

The harassment and dispossession of American Indians—whether driven by official U.S. government policy or the actions of individual Americans and their communities—depended on the belief in manifest destiny. Of course, a fair bit of racism was part of the equation as well. The political and legal processes of expansion always hinged on the belief that white Americans could best use new lands and opportunities. This belief rested on the idea that only Americans embodied the democratic ideals of yeoman agriculture extolled by Thomas Jefferson and expanded under Jacksonian democracy.

Florida was an early test case for the Americanization of new lands. The territory held strategic value for the young nation’s growing economic and military interests in the Caribbean. The most important factors that led to the annexation of Florida included anxieties over runaway slaves, Spanish neglect of the region, and the desired defeat of Native American tribes who controlled large portions of lucrative farm territory.

Americans also held that Creek and Seminole Indians, occupying the area from the Apalachicola River to the wet prairies and hammock islands of central Florida, were dangers in their own right. These tribes, known to the Americans collectively as Seminoles, migrated into the region over the course of the eighteenth century and established settlements, tilled fields, and tended herds of cattle in the rich floodplains and grasslands that dominated the northern third of the Florida peninsula. Envious eyes looked upon these lands. After bitter conflict that often pitted Americans against a collection of Native Americans and former slaves, Spain eventually agreed to transfer the territory to the United States. The resulting Adams-Onís Treaty exchanged Florida for $5 million and other territorial concessions elsewhere.[1]

After the purchase, planters from the Carolinas, Georgia, and Virginia entered Florida. However, the influx of settlers into the Florida territory was temporarily halted in the mid-1830s by the outbreak of the Second Seminole War (1835–1842). Free black men and women and escaped slaves also occupied the Seminole district, a situation that deeply troubled slave owners. Indeed, General Thomas Sidney Jesup, U.S. commander during the early stages of the Second Seminole War, labeled that conflict “a negro, not an Indian War,” fearful as he was that if the revolt “was not speedily put down, the South will feel the effect of it on their slave population before the end of the next season.”[2] Florida became a state in 1845 and settlement expanded into the former Indian lands.

American action in Florida seized Indians’ eastern lands, reduced lands available for runaway slaves, and killed entirely or removed Indian peoples farther west. This became the template for future action. Presidents, since at least Thomas Jefferson, had long discussed removal, but President Andrew Jackson took the most dramatic action. Jackson believed, “It [speedy removal] will place a dense and civilized population in large tracts of country now occupied by a few savage hunters.”[3] Desires to remove American Indians from valuable farmland motivated state and federal governments to cease trying to assimilate Indians and instead plan for forced removal.

Congress passed the Indian Removal Act in 1830, thereby granting the president authority to begin treaty negotiations that would give American Indians land in the West in exchange for their lands east of the Mississippi. Many advocates of removal, including President Jackson, paternalistically claimed that it would protect Indian communities from outside influences that jeopardized their chances of becoming “civilized” farmers. Jackson emphasized this paternalism—the belief that the government was acting in the best interest of Native peoples—in his 1830 State of the Union Address. “It [removal] will separate the Indians from immediate contact with settlements of whites . . . and perhaps cause them gradually, under the protection of the Government and through the influence of good counsels, to cast off their savage habits and become an interesting, civilized, and Christian community.”[4]

The experience of the Cherokee was particularly brutal. Despite many tribal members adopting some Euro-American ways, including intensified agriculture, slave ownership, and Christianity, state and federal governments pressured the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Cherokee Nations to sign treaties and surrender land. Many of these tribal nations used the law in hopes of protecting their lands. Most notable among these efforts was the Cherokee Nation’s attempt to sue the state of Georgia.

Beginning in 1826, Georgian officials asked the federal government to negotiate with the Cherokee to secure lucrative lands. The Adams administration resisted the state’s request, but harassment from local settlers against the Cherokee forced the Adams and Jackson administrations to begin serious negotiations with the Cherokee. Georgia grew impatient with the process of negotiation and abolished existing state agreements with the Cherokee that had guaranteed rights of movement and jurisdiction of tribal law. Andrew Jackson penned a letter soon after taking office that encouraged the Cherokee, among others, to voluntarily relocate to the West. The discovery of gold in Georgia in the fall of 1829 further antagonized the situation.

The Cherokee defended themselves against Georgia’s laws by citing treaties signed with the United States that guaranteed the Cherokee Nation both their land and independence. The Cherokee appealed to the Supreme Court against Georgia to prevent dispossession. The Court, while sympathizing with the Cherokee’s plight, ruled that it lacked jurisdiction to hear the case (Cherokee Nation v. Georgia [1831]).

Jackson wanted a solution that might preserve peace and his reputation. He sent secretary of war Lewis Cass to offer title to western lands and the promise of tribal governance in exchange for relinquishing of the Cherokee’s eastern lands. These negotiations opened a rift within the Cherokee Nation. Cherokee leader John Ridge believed removal was inevitable and pushed for a treaty that would give the best terms. Others, called nationalists and led by John Ross, refused to consider removal in negotiations. The Jackson administration refused any deal that fell short of large-scale removal of the Cherokee from Georgia, thereby fueling a devastating and violent intra-tribal battle between the two factions.

In 1835, a portion of the Cherokee Nation led by John Ridge, hoping to prevent further tribal bloodshed, signed the Treaty of New Echota. This treaty ceded lands in Georgia for $5 million and, the signatories hoped, limiting future conflicts between the Cherokee and white settlers. However, most of the tribe refused to adhere to the terms, viewing the treaty as illegitimately negotiated.

President Martin van Buren, in 1838, decided to press the issue beyond negotiation and court rulings and used the New Echota Treaty provisions to order the army to forcibly remove those Cherokee not obeying the treaty’s cession of territory. Harsh weather, poor planning, and difficult travel compounded the tragedy of what became known as the Trail of Tears. Sixteen thousand Cherokee embarked on the journey; only ten thousand completed it.

Despite the disaster of removal, tribal nations slowly rebuilt their cultures and in some cases even achieved prosperity in Indian Territory. Tribal nations blended traditional cultural practices, including common land systems, with western practices including constitutional governments, common school systems, and creating an elite slaveholding class.

- Francis Newton Thorpe, ed., The Federal and State Constitutions, Colonial Charters, and Other Organic Laws of the States, Territories, and Colonies Now or Heretofore Forming the United States of America Compiled and Edited Under the Act of Congress of June 30, 1906 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1909.

- Thomas Sidney Jesup, quoted in Kenneth Wiggins Porter, “Negroes and the Seminole War, 1835–1842,” Journal of Southern History 30, no. 4 (November 1964): 427.

- “President Andrew Jackson’s Message to Congress ‘On Indian Removal’ (1830).” http://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=true&doc=25&page=transcript, accessed May 26, 2015.

- “President Andrew Jackson’s Message to Congress ‘On Indian Removal’ (1830).” http://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=true&doc=25&page=transcript, accessed May 26, 2015.

- Russell Thornton, The Cherokees: A Population History (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1990), p. 76.

From Chapter 12, “Manifest Destiny,” The American Yawp: A Massively Collaborative Open U.S. History Textbook (Stanford University Press Edition, CC BY-SA 4.0)

4. Discussion questions

Kaphar’s painting uses defacement as a way of critiquing Andrew Jackson. What other examples of defacement can you think of, from history, the news, or from your daily life (such as painting on a sign or billboard, or even scribbling a mustache on a picture of a person in a book)? Why do you think people do this—is it simply to make trouble (as is often claimed), or is there a deeper reason behind the drive to intervene on “official” images? How does Kaphar use the same approach to make a powerful statement?

5. Research question

Andrew Jackson and Donald Trump are both often described as “populists.” What is populism? What do people mean when they use that term to describe these two presidents?

6. Bibliography

This painting at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

“Can Art Amend History?” TED Talk with Titus Kaphar (April 2017)

Meet The MacArthur Fellow Disrupting Racism In Art on NPR (October 2018)

Indian Removal Act: Primary Documents in American History (Library of Congress)

Indian Removal (Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History)

A. J. Langguth, Driven West: Andrew Jackson and the Trail of Tears to the Civil War (Simon and Schuster, 2010)