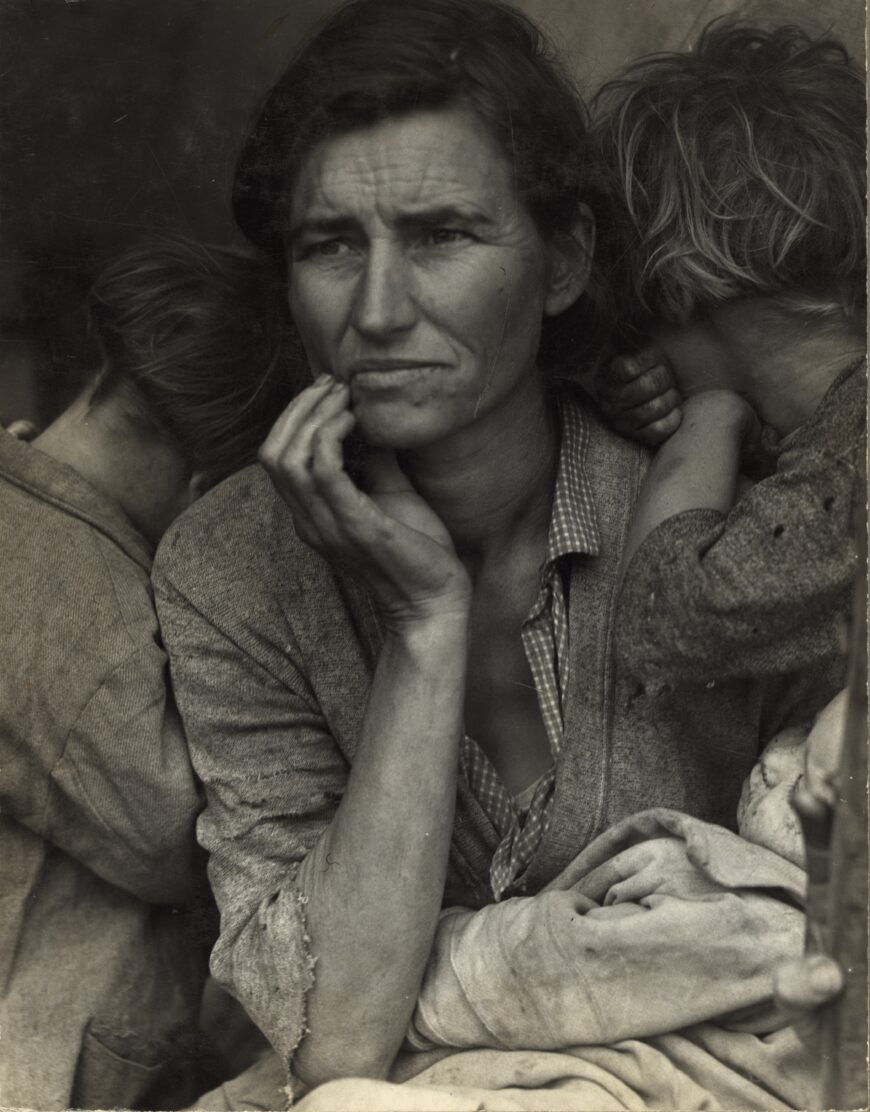

![Florence Owens’s grandson, Roger Sprague, identified the subjects, from left to right, as: “Katherine Owens age 4, Florence Owens (later known as Thompson) age 32, Ruby Owens age 5. Baby on mother's lap is Norma age 1 year.” [1] Dorothea Lange, Migrant Mother / Destitute Pea Pickers in California, Mother of Seven Children. Age Thirty-Two. Nipomo, California, 1936, digital reproduction from retouched negative (Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Lange-migrant-mother-870x1085.jpg)

Florence Owens’s grandson, Roger Sprague, identified the subjects, from left to right, as: “Katherine Owens age 4, Florence Owens (later known as Thompson) age 32, Ruby Owens age 5. Baby on mother’s lap is Norma age 1 year.” [1] Dorothea Lange, Migrant Mother / Destitute Pea Pickers in California, Mother of Seven Children. Age Thirty-Two. Nipomo, California, 1936, digital reproduction from retouched negative (Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.)

I didn’t want to stop, and didn’t. I didn’t want to remember that I had seen it, so I drove on and ignored the summons. … Having well convinced myself for twenty miles that I could continue on, I did the opposite. Almost without realizing what I was doing, I made a U-turn on the empty highway. [3]

She eventually did turn around, and toward the camp of 2,500 out-of-work migratory agriculture workers. At that moment, Lange noticed what she described as a “hungry and desperate mother” surrounded by her children and crowded under a makeshift tent. She took seven photographs—only five were deemed by Lange to be good enough to send to Washington, D.C., after she retouched the negative to make a thumb at the right edge of the picture plane of the Migrant Mother less apparent to viewers. [4]

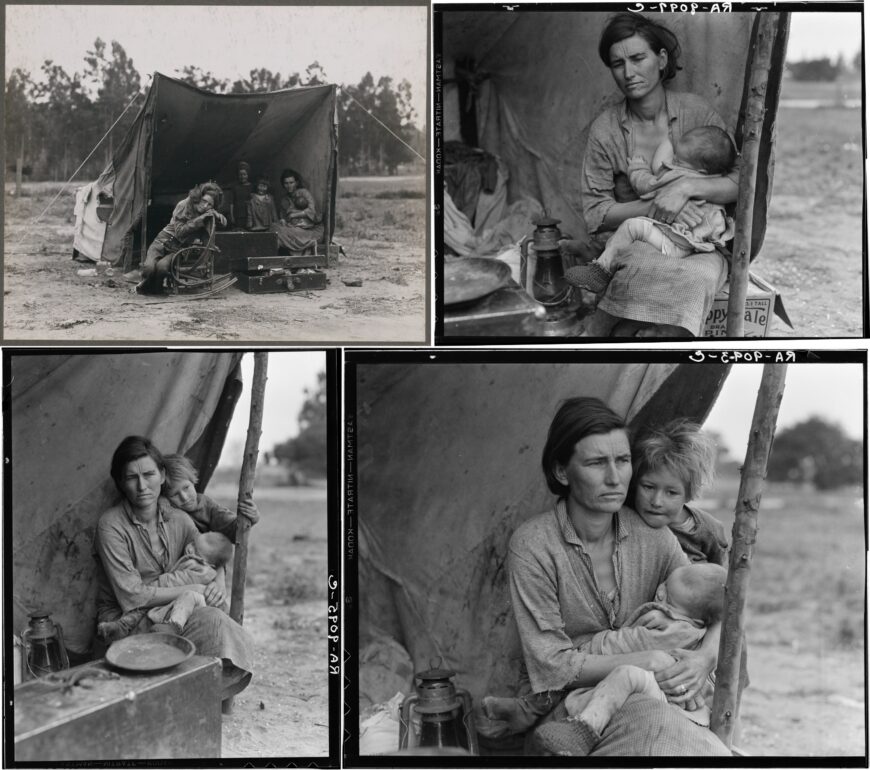

Dorothea Lange, four other frames from the Migrant Mother shoot, 1936 (Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.: upper left; upper right; lower left; lower right)

In an account written in 1960, Lange describes her interaction with the central figure of the photograph (originally titled Destitute Pea Pickers in California. Mother of Seven Children. Age Thirty-Two. Nipomo, California), a newly widowed, Cherokee woman, Florence Owens, who shortly would become known as “Migrant Mother”:

I did not ask her name or her history. She told me her age, that she was thirty-two. She said that they had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed. She had just sold the tires from her car to buy food. There she sat in that lean-to tent with her children huddled around her, and seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me. There was a sort of equality about it. The pea crop at Nipomo had frozen and there was no work for anybody. But I did not approach the tents and shelters of other stranded pea-pickers. It was not necessary; I knew I had recorded the essence of my assignment. [5]

The making of an iconic photograph

The essence of Lange’s assignment—and the mission of all Resettlement Administration/Farm Security Administration photographers’ work—was to capture iconic, memorable images of agricultural workers that roused support for President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal relief programs. Migrant Mother—which reveals an anxious mother holding a baby as two of her other children bury their heads on her shoulders—draws on the familiar trope of the Madonna and Child in Christian art as it evokes sympathy and, ideally, a spirit of humanitarian generosity toward its subjects.

Dorothea Lange, Migrant Mother, digital file of black-and-white film copy negative of unretouched file print showing thumb holding a tent pole in the lower right corner (Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.)

Lange’s supervisor, Roy Stryker, believed this image encapsulated the goals of RA/FSA most succinctly:

When Dorothea took that picture, that was the ultimate. She never surpassed it. To me, it was the picture of Farm Security. The others were marvelous but that was special. [6]

As an icon, the photograph Migrant Mother is larger than one woman’s story. Instead, the pictured mother stands for the plight of suffering, poverty, and uncertainty among rural laborers during the Great Depression. Migrant Mother immediately was (and still is) circulated by the U.S. government, free of charge, to the press and the public. [7]

This was among the first publications of photographs from Lange’s Migrant Mother series, which were taken in late February or early March of 1936. The San Francisco News, March 10, 1936

Beyond iconicity: misrepresenting Migrant Mother’s story

Migrant Mother provided such a persuasive, straightforward, and iconic image of a destitute, worried mother concerned about providing for her children that a sympathetic public and government sent a total of $200,000 in aid and free medical care to the pea-picker’s camp three days later. [8] Sadly, by that time, Owens and her children already had moved on to find other work. She never got to take advantage of the “help” Lange promised the photograph would bring.

Despite caption information provided by Lange, Owens’s family did have a car, which her soon-to-be future husband (Jim Hill) had taken to buy parts and repair. [9] That car had all of its tires, and Hill would return in it to retrieve Owens and her 6 (not 7) children, so they could leave the 2,500-person pea-picker’s camp, which would shortly be raided by locals who arrested and beat its remaining inhabitants. [10]

As historian Milton Meltzer noted, Lange’s caption-writing and note-taking habits were lax, and tracking the details of her subjects and their circumstances frequently took a backseat to photographing. [11] Lange acknowledged these allegations of misrepresenting Owens, and claimed that the image did more good than harm.

Living in the shadow of the photograph’s iconicity

Although Owens and her children were not abandoned to starve to death, and would survive the Great Depression, she resented being associated with the Migrant Mother photograph for the rest of her life, her daughter attests: “She was a very strong woman. She was a leader. I think that’s one of the reasons she resented the photo — because it didn’t show her in that light.” [12] Rather, the iconic image transcended Owens’s actual story and became a part of a U.S. macro-narrative of suffering and motherly fortitude during the Great Depression.

Owens—a woman of color—felt forever stereotyped as the destitute, suffering mother, trapped in poverty by the repeated reproductions of her image that appeared in newspapers, magazines, art exhibitions, on the pages of our history books, and on postage stamps, t-shirts, parodic magazine illustrations, and trinkets. In 1958, after Migrant Mother was included in exhibitions and published widely for two decades, Owens wrote a letter to one publication, U.S. Camera, and insisted on being consulted about future plans to publish the image. She asked for all copies of that issue of U.S. Camera to be recalled. [13] Because neither Lange nor any of the publications made money from the photograph, they did not offer Owens compensation. Instead, Lange apologized and offered sympathy to the woman whose individual story and likeness were co-opted to fulfill a political program’s narrative.

Notes:

[1] Roger Sprague, “Migrant Mother: The Story as Told By Her Grandson.”

[2] Martha Rosler, Decoys and Disruptions: Selected Writings, 1975–2001 (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2004), p. 184. In this essay, Rosler suggests that Migrant Mother was the most widely reproduced photograph in the world.

[3] Dorothea Lange, “The Assignment I’ll Never Forget,” Popular Photography (Feb. 1960), pp. 42–43, 128. Reprinted in Illuminations: Women Writing on Photography from the 1850s to the Present, edited by Liz Heron and Val Williams (New York: I.B. Taurus, 1996), pp. 151–52.

[4] Sarah Meister, “Piecing Together Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother,” Museum of Modern Art (Feb. 6, 2020).

[5] Lange, “The Assignment I’ll Never Forget” (1960), in Illuminations (1996) pp. 151–52. In many accounts, Florence Owens is identified as Florence Owens Thompson. However, she would not marry George Basil Thompson until 1949, and kept the name Owens after the death of her first husband, Cleo Owens, in 1931: “Florence Owens Hills,” April 16, 1940, Census Records, Kern County, California, Sheet 8B, S.D. No.10, E.D. Nos. 15–44, Line 75. Department of Commerce—Bureau of the Census.

[6] Milton Meltzer, Dorothea Lange: A Photographer’s Life (New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1978), p. 133. Italics are Meltzer’s emphasis.

[7] See “Dorothea Lange’s ‘Migrant Mother’ Photographs in the Farm Security Administration Collection,” Library of Congress.

[8] Linda Gordon, Dorothea Lange: A Life Beyond Limits (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2009), p. 237. The photograph was first published in The San Francisco News on March 10, 1936.

[9] Sprague, “Migrant Mother.”

[10] Gordon (2009), pp. 236–37.

[11] Meltzer (1978), p. 131.

[12] Owens’s unnamed daughter is quoted in: Geoffrey Dunn, “Photographic License,” San Jose Metro (January 19–25, 1995), p. 22.

[13] Gordon (2009), p. 241.

Additional resources

This photograph at the Library of Congress

Linda Gordon, Dorothea Lange: A Life Beyond Limits (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2009).

Robert Hariman and John Louis Lucaites, No Caption Needed: Iconic Photographs, Public Culture, and Liberal Democracy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), pp. 53–67 (excerpt here).

Sarah Meister, Dorothea Lange: Migrant Mother (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2019).

Sally Stein, Migrant Mother, Migrant Gender (London: MACK Books, 2020).

Test your knowledge with a quiz

Lange, Migrant Mother

Key points

- In this iconic photograph, Dorothea Lange captured the suffering of migrant workers affected by the Dust Bowl and the economic fallout of the Great Depression. Lange highlights the impact of these events on farmers and agricultural laborers, who were less visible than urban unemployed masses.

- With as much as 25% of Americans unemployed during the Great Depression, Roosevelt’s New Deal created a social safety net and spurred economic growth. Lange was commissioned by the Resettlement Administration (which later became the Farm Security Administration) to capture images that would rally support for these new government programs. The immediate success of this photograph brought much-needed assistance to these farm workers.

- Lange’s photograph documents an economic story, but also creates a personal narrative. By closely framing the distant gaze of the woman, surrounded by her children, she encourages our empathy. The photograph is both a factual record and an interpretive work of art.

- Lange’s subject, Florence Owens Thompson, was living in northern California, a destination for many displaced migrant farm workers who were often referred to by the derogatory term, “Okies.” Her story, however, is more complicated since Thompson had been in California for nearly a decade. She was also Cherokee, so her family had most likely been forced to relocate to Oklahoma under the Indian Removal Act of 1830, connecting her to a larger history of American migration and displacement.

Go deeper

Explore an online exhibition on the Great Depression and Roosevelt’s New Deal

Explore the types of photographs sponsored by the FSA

Read more about Dorothea Lange at MoMA

Watch an interview with two of Florence Owens Thompson’s children.

Read and see a clip from Ken Burns’ The Dust Bowl about Lange’s role in its documentation.

More to think about

Dorothea Lange used photography as an activist, building empathy and awareness through her images. Think about a current social issue that is important to you. Are there visual images that have influenced the way you feel about this issue? Why do you think photography might be an effective tool of persuasion?

In the video, we see other photographs that Dorothea Lange took of Florence Owens Thompson. Imagine that you are writing a letter to the Farm Security Administration, suggesting that they use this particular picture. What argument would you make?

Dorothea Lange’s photograph documents reality, but also encourages the viewer to interpret what is happening. Each week, The New York Times publishes a photograph without a caption and invites students to discuss what they see and what they think it means. Visit https://www.nytimes.com/column/learning-whats-going-on-in-this-picture and join a moderated conversation about how photographs can tell stories.