An American hero sculpted by a foreigner

After the successful conclusion of the American Revolutionary War, many state governments turned to public art to commemorate the occasion. Given his critical role in both Virginia and the colonial cause, it is unsurprising that the Virginia General Assembly desired a statue of George Washington for display in a public space.

And so, in 1784, the Governor of Virginia asked Thomas Jefferson (another Virginian who was then in Paris as the American Minister to France) to select an appropriate artist to sculpt Washington. Seeking a European sculptor—and for Jefferson, whose Francophile sympathies were clear, preferably one who was French—was a logical decision given the lack of artistic talent then available in the United States. Through basic necessity, this portrait of an American hero needed to be made by a foreigner.

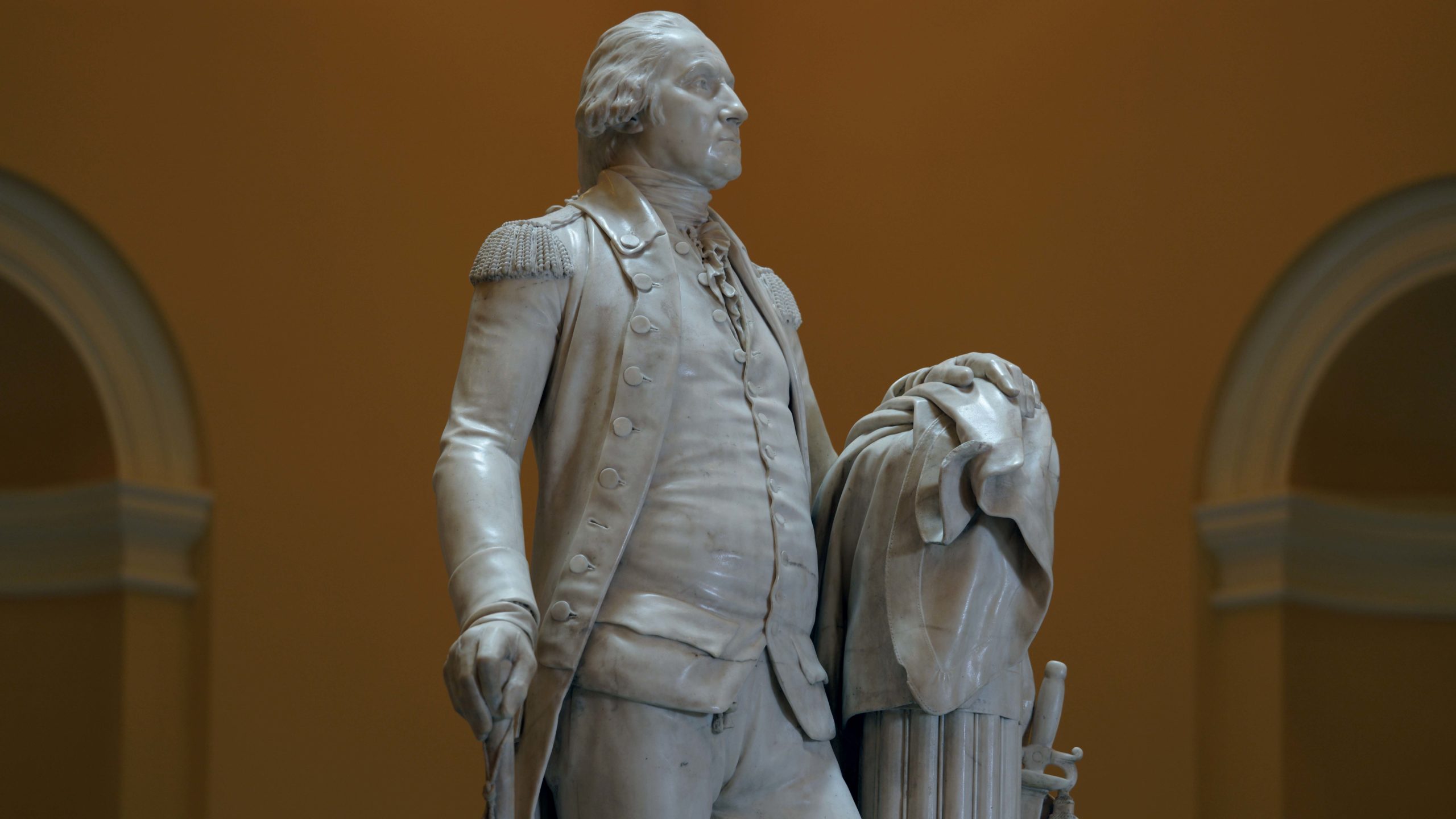

Jean-Antoine Houdon, George Washington, 1788–92, marble, 6′ 2″ high (State Capitol, Richmond, Virginia, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Jefferson knew just the artist for this task: Jean-Antoine Houdon. Trained at the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture and winner of the prestigious Prix de Rome in 1761 when only twenty years of age, Houdon was, by the middle of the 1780s, the most famous and accomplished Neoclassical sculptor in France.

Jefferson commissioned Houdon to complete a monumental statue of Washington. Given Houdon’s skill and ambition, the sculptor likely hoped to cast a larger-than-life-sized bronze statue of General Washington on horseback, a format appropriate for a victorious field commander. However, the final product, delivered more than a decade later, was a comparatively simple standing marble.

Evidence suggests that Houdon was supposed to remain in Paris and sculpt Washington from a drawing by Charles Willson Peale. Uncomfortable with carving in three dimensions what Peale had rendered in only two, Houdon made plans to visit Washington in person. Houdon departed for the United States in July 1785 and was joined by Benjamin Franklin—who he had sculpted in 1778—and two assistants. The group sailed into Philadelphia about seven weeks later and Houdon and his assistants arrived at Mount Vernon (Washington’s home in Virginia) by early October. There they took detailed measurements of Washington’s body and sculpted a life mask of the future president’s face.

Jean-Antoine Houdon, George Washington, 1788–92, marble, 6′ 2″ high (State Capitol, Richmond, Virginia, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Contemporary clothing (and not a toga)

While in Virginia, Houdon created a slightly idealized and classicized bust portrait of the future first president. But Washington disliked this classicized aesthetic and insisted on being shown wearing contemporary attire rather than the garments of a hero from ancient Greece or Rome. With clear instructions from the sitter to be depicted in contemporary dress, Houdon returned to Paris in December 1785 and set to work on a standing full-length statue carved from Carrara marble. Although Houdon dated the statue 1788, he did not finish it until about four years later. The statue was delivered to the State of Virginia in May of 1796, when the Rotunda of the Virginia State Capitol was finally completed.

“Nothing in bronze or stone could be a more perfect image…”

Jean-Antoine Houdon, George Washington, 1788–92, marble, 6′ 2″ high (State Capitol, Richmond, Virginia, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In time, this statue of George Washington has become one of the most recognized and copied of images of the first president of the United States. Houdon did not just perfectly capture Washington’s likeness (John Marshal, the second Chief Justice of the Supreme Court later wrote, “Nothing in bronze or stone could be a more perfect image than this statue of the living Washington”). Houdon also captured the essential duality of Washington: the private citizen and the public solider.

Washington stands and looks slightly to his left; his facial expression could best be described as fatherly. He wears not a toga or other classically inspired garment, but his military uniform. His stance mimics that of the contrapposto seen in Polykleitos’s classical sculpture of Doryphoros. Washington’s left leg is slightly bent and positioned half a stride forward, while his right leg is weight bearing. His right arm hangs by his side and rests atop a gentleman’s walking stick.

His left arm—bent at the elbow—rests atop a fasces: a bundle of thirteen rods that symbolize not only the power of a ruler but also the strength found through unity. This visually represents the concept of E Pluribus Unum—”Out of Many, One”—a congressionally approved motto of the United States from 1782 until 1956.

Washington’s officer’s sword, a symbol of military might and authority, benignly hangs on the outside of the fasces, just beyond his immediate grasp. This surrendering of military power is further reinforced by the presence of the plow behind him. This refers to the story of Cincinnatus, a Roman dictator who resigned his absolute power when his leadership was no longer needed so that he could return to his farm. Like this Roman, Washington resigned his power and returned to his farm to live a peaceful, civilian life.

Washington as soldier and private citizen

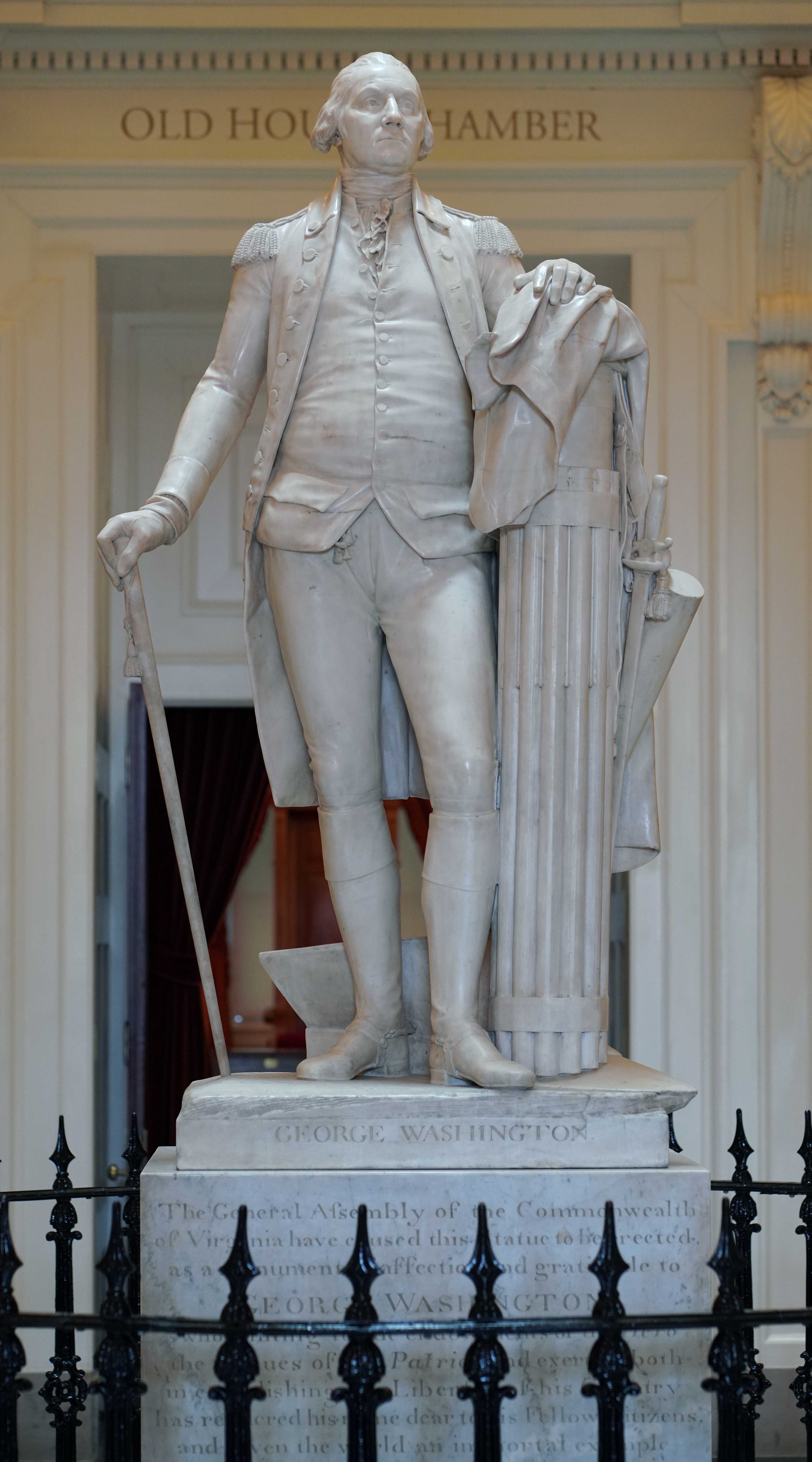

Horatio Greenough, George Washington, 1840, marble, 136 x 102 inches, National Museum of American History (photo: Gary Todd, public domain)

The statue, still on view in the Rotunda of the Virginia State Capitol, is a near perfect representation of the first president of the United States of America. In it, Houdon captured not only what George Washington looked like, but more importantly, who Washington was, both as a soldier and as a private citizen.

The enormously talented Houdon wisely accepted Washington’s advice. Indeed, Washington knew it was better to be subtly compared to Cincinnatus than to be overtly linked to Caesar, another Roman who, unlike Cincinnatus, did not surrender his power.

To compare Houdon’s statue to Horatio Greenough’s 1840 statue of Washington only makes this salient point more clear. With the sitter’s urging, Houdon opted for subtlety, whereas Greenough decided two generations later to fully embrace a neoclassical aesthetic. As a result, Houdon’s statue celebrates Washington the man, whereas Greenough deified Washington as a god.

Test your knowledge with a quiz

Houdon, George Washington

Key points

- This life-sized sculpture of George Washigton was created to honor the general for his leadership of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War (1775-83). At the time of the commission in 1784, Washington had resigned from his military post and returned to his plantation at Mount Vernon to resume the life of a country gentleman (although by the time the sculpture was completed and installed in 1796, Washington had been elected and completed almost two terms as the first president of the United States).

- For viewers–from 1796 until today–Jean-Antoine Houdon’s sculpture has symbolized the varied roles that Washington held and the values he reflected for the young nation: the heroism of a military commander, the wisdom and dedication of a democratic statesman, and the self-determined pursuits of a private citizen. These facets of his identity are reflected in the contrasting details of the sculpture, such as the sword and walking stick or the fasces and the plow, and in its placement in the classicizing rotunda of Virginia’s capitol building, the seat of the state’s government.

- Houdon employed neoclassicism in both style and symbolism. The white marble and contrapposto of the figure are features borrowed from ancient Roman sculpture. And, Washington’s portrayal as a leader who honorably relinquished his power to return to his life as a farmer recalls the revered story of the ancient Roman general Cincinnatus.

- In preparation for carving the sculpture, French artist Houdon traveled to Virginia to make a life cast of Washington’s face and take body measurements. Although Houdon’s work is therefore considered to be one of the most accurate portrayals of the general’s physical likeness, today we recognize the elements of George Washington that a sculpture like this does not reveal. Notably, the fact that he was a slave owner and was at times brutal in his treatment of his enslaved laborers.

Go deeper

Houdon on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Neo-Classicism on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Explore resources from George Washington’s Mount Vernon, which exists as a museum and historic site today. Topics include portraits of George Washington, the work of Jean-Antoine Houdon, and slavery.

Listen to the podcast, Intertwined: The Enslaved Community at George Washington’s Mount Vernon.

Read about the history of the treatment of Houdon’s sculpture of George Washington and recent conservation efforts from the Colonial Williamsburg Journal.

Learn about other images of George Washington featured on Smarthistory, including the Lansdowne Portrait and Grant Wood’s Parson Weems’ Fable.

More to think about

For almost 250 years, portraits of George Washington have represented to viewers his visionary and democratic leadership. The portraits promote a mythology, however, that obscures less admirable details of his power and privilege (namely his status as an enslaver). Can you think of public images of leaders in U.S. government and society today that operate in a similar fashion? What might they owe to the portrayals of George Washington and what stands out as different from that tradition?

Research project

Houdon’s portrait of Washington captures the aspirations of a young nation for a particular form of democratic leadership. Compare Houdon’s portrait with that of a newly established leader from a different place and time, operating under a different type of leadership and power. How are they similar and different in terms of style and iconography? Here are a few examples to choose from, or select other examples that you would like to explore:

- Roman, Augustus of Primaporta, 1st century C.E.

- Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Napoleon on His Imperial Throne, 1806

- Richard Evans, Portraits of the Caribbean’s first Black king and prince, c. 1816

- Portraits of Elizabeth I: Fashioning the Virgin Queen, 16th century

- Queen Lili’uokalani’s accession photograph

Note: When making comparisons among these portraits, be sure to consider the unique historical and cultural context of each, refraining from assumptions that might impose bias on the subject.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”jeanantoinehoudon”]