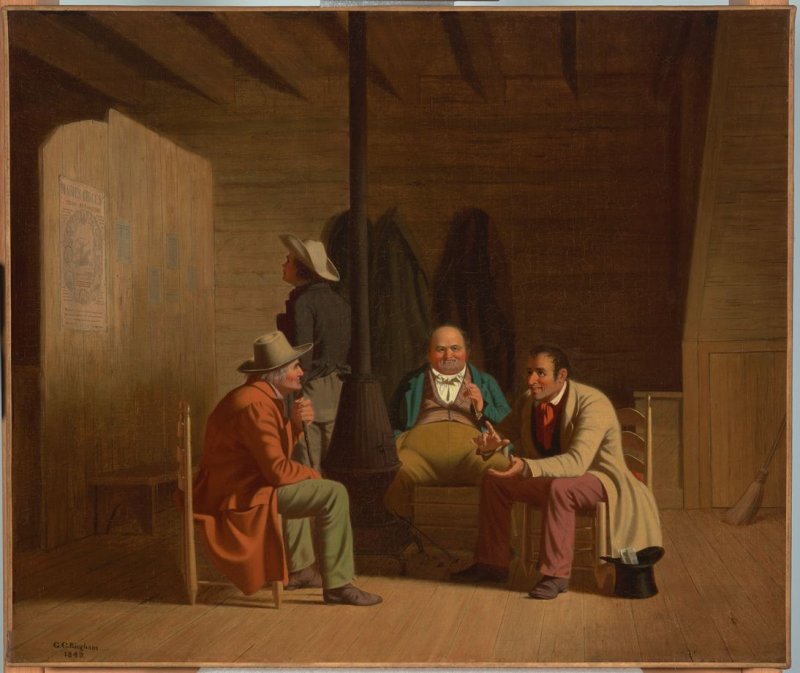

George Caleb Bingham, Country Politician (detail), 1849, oil on canvas, 51.8 x 61cm (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco).

The Missouri Compromise and the dangerous precedent of appeasement

Essay by Dr. Kimberly Kutz Elliott

“This momentous question, like a fire bell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror. I considered it at once as the knell of the Union.” —Thomas Jefferson on the westward expansion of slavery, 1820

Compromise or appeasement?

Thomas Jefferson, third president of the United States and aged leader of his party, wrote during the Missouri Controversy of 1820 that the westward expansion of slavery would lead to the “[death] knell of the Union.”[1] Jefferson was right, if a little premature; Congress held the union together for another forty years through compromises before slave states finally seceded and brought on the Civil War in 1861. The Missouri Compromise was one of many such attempts to prevent the union from fracturing over slavery, and it established the model for maintaining a balance of power between free and slave states that lasted until the 1850s.

For many years, historians celebrated these compromises as valiant efforts to save the union, but more recently, historians have begun to question whether they should instead be characterized as appeasements of slaveholders, who often got the better end of the bargain.[2]

People and terms

| Democratic-Republicans | Democratic-Republicans were members of an early American political party that championed state and local government, westward expansion, and the interests of farmers. |

| Northwest Ordinance | The Northwest Ordinance (1787) organized the region surrounding the Great Lakes into a territory where slavery was prohibited. |

| James Monroe | James Monroe served as president from 1817–1825. He was a member of the Democratic-Republican party and today is most famous for the “Monroe Doctrine,” which opposed further European colonization of Latin America. |

| Three-Fifths Clause | The Three-Fifths Clause is part of Article I, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution, which determines how seats in the House of Representatives are apportioned according to state population. The Framers of the Constitution agreed to count three-fifths (60%) of the enslaved people living in a state as part of its population (even though enslaved people had no citizenship rights and could not vote). This gave southern states more power than they would have wielded otherwise. |

| Louisiana Purchase | The Louisiana Purchase was a land deal between France and the United States, which purchased the right to acquire territory belonging to Indigenous peoples between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains. |

| Gradual emancipation | Gradual emancipation was a method of phasing out the institution of slavery over time favored by many northern state legislatures in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. |

| Henry Clay | Henry Clay was a Kentucky statesman who served as Speaker of the House and Secretary of State. He was called the “Great Compromiser” for his role in brokering compromises between northerners and southerners. |

| Privileges and immunities clause | The privileges and immunities clause in the Constitution prevents states from treating citizens of other states in a discriminatory manner. |

Bad feelings in the Era of Good Feelings

The U.S. political sphere after the conclusion of the War of 1812 has often been called the “Era of Good Feelings,” a rare period when there was only one active political party in the United States (the Democratic-Republicans) and President James Monroe promoted national pride and unity. But the lack of party divisions soon revealed deeper fissures in American politics: between northerners, who opposed the expansion of slavery, and southerners, who balked at any attempt to restrict human bondage. These divisions—and their potential to break apart the United States—came into sharp focus during the controversy over the admission of the state of Missouri.

This enormous history painting by John Trumbull, who briefly served in the Continental Army, depicts the “Committee of Five” (including John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and Ben Franklin, standing in the center) presenting the draft of the Declaration of Independence to the Continental Congress. Trumbull worked on this painting for nearly thirty years, beginning with a sketch of the event made by Thomas Jefferson himself, and traveling to visit many of the participants so he could paint them from life. In 1817, in a period of increased national pride, Congress voted to commission Trumbull to paint a large-scale version to hang in the U.S. Capitol building rotunda. John Trumbull, The Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776, 1818 (placed 1826), oil on canvas, 12 x 18 feet (Rotunda, U.S. Capitol).

In 1819, more than forty years after the Founders signed the Declaration of Independence, a new generation of statesmen emerged onto the American political stage. Some, like John Quincy Adams, were the actual children of the Founders; others, like Monroe, were merely their spiritual heirs. In either case, they were beginning to chafe at some of their forebears’ choices. Northerners resented the amount of influence that southerners exercised in the government: the “Three-Fifths Clause” in the Constitution gave slave states undeserved power in the House of Representatives, and Virginians had controlled the presidency for twenty-six out of the thirty years the office had existed.

For their part, southerners regretted the precedent set by the Northwest Ordinance and the ban on the international slave trade, which suggested that the federal government had the power to regulate slavery outside of southern states. When Congress passed those acts in the late eighteenth century, slavery seemed like a dying institution, but the introduction of the cotton gin revived its profitability. By 1820, white southerners were more committed to enslaving and selling Black men, women, and children than ever before.

The balance of power, the Missouri controversy, and “gradual emancipation”

Both sides knew that their fortunes ultimately depended on the west, where new states would determine the balance of congressional power. The U.S. government had gained over 800,000 acres of land through the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, and white settlers had begun carving future states out of these Indigenous lands. The state of Louisiana was the first to enter the union from the territory; Missouri was not far behind.

An 1820 scene of everyday life in Brooklyn, New York, includes several Black figures, who may have been enslaved, in the right foreground, showing the social hierarchy of early nineteenth-century New York. James Tallmadge Jr., whose proposal for gradual emancipation in Missouri ignited a firestorm in Congress, had recently championed a similar plan for the enslaved people of New York. Francis Guy, Winter Scene in Brooklyn, 1820, oil on canvas, 147.3 x 260.2 cm (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art).

In February 1819, the House of Representatives began to consider the Missouri Territory’s request to organize a state government. That Missouri would soon enter the union as a slave state seemed likely, until New York Representative James Tallmadge Jr. proposed an amendment to the bill. The Tallmadge amendment provided for the gradual emancipation of enslaved people in Missouri: although no enslaved person currently residing in Missouri would be freed, no more enslaved people could be brought into the state and any children born to enslaved people there would be free at the age of 25. This plan was quite similar to one recently adopted by the state of New York, which had the largest enslaved population among northern states.

The amendment stirred up such a controversy in Congress that its members threatened civil war. Tallmadge himself professed that “If a dissolution of the Union must take place, let it be so! If civil war, which gentlemen so much threaten, must come, I can only say, let it come!”[3] Supporters of the amendment argued that the Northwest Ordinance showed that the Founders had intended to prevent slavery’s expansion into new territories. Thomas Jefferson, who had been one of those Founders, now promoted the disingenuous “diffusion” argument that expanding slavery into new territories would actually help to bring about its eventual demise.[4] Opponents of the amendment countered that slavery had continued unabated in Louisiana following its organization as a territory and state. Why should Missouri be any different?

The vote on the amendment’s provisions brought sectional divisions into sharp relief: in the House, where northerners had the population advantage, the bill passed; in the Senate, where states had equal representation, it failed. Congress could not resolve the issue in its February session, and the question of Missouri’s statehood had to wait until December.

Maine, Missouri, and another compromise

While Congress was adjourned, the Massachusetts legislature voted to permit what was then the District of Maine to organize as a separate state. When Congress reconvened in December, pro-slavery Senate leaders put the Maine and Missouri questions into a single bill, in an attempt to make approving slavery in Missouri a condition of admitting Maine as a state. This measure passed the Senate but not the House, whose majority still hoped to keep slavery out of Missouri.

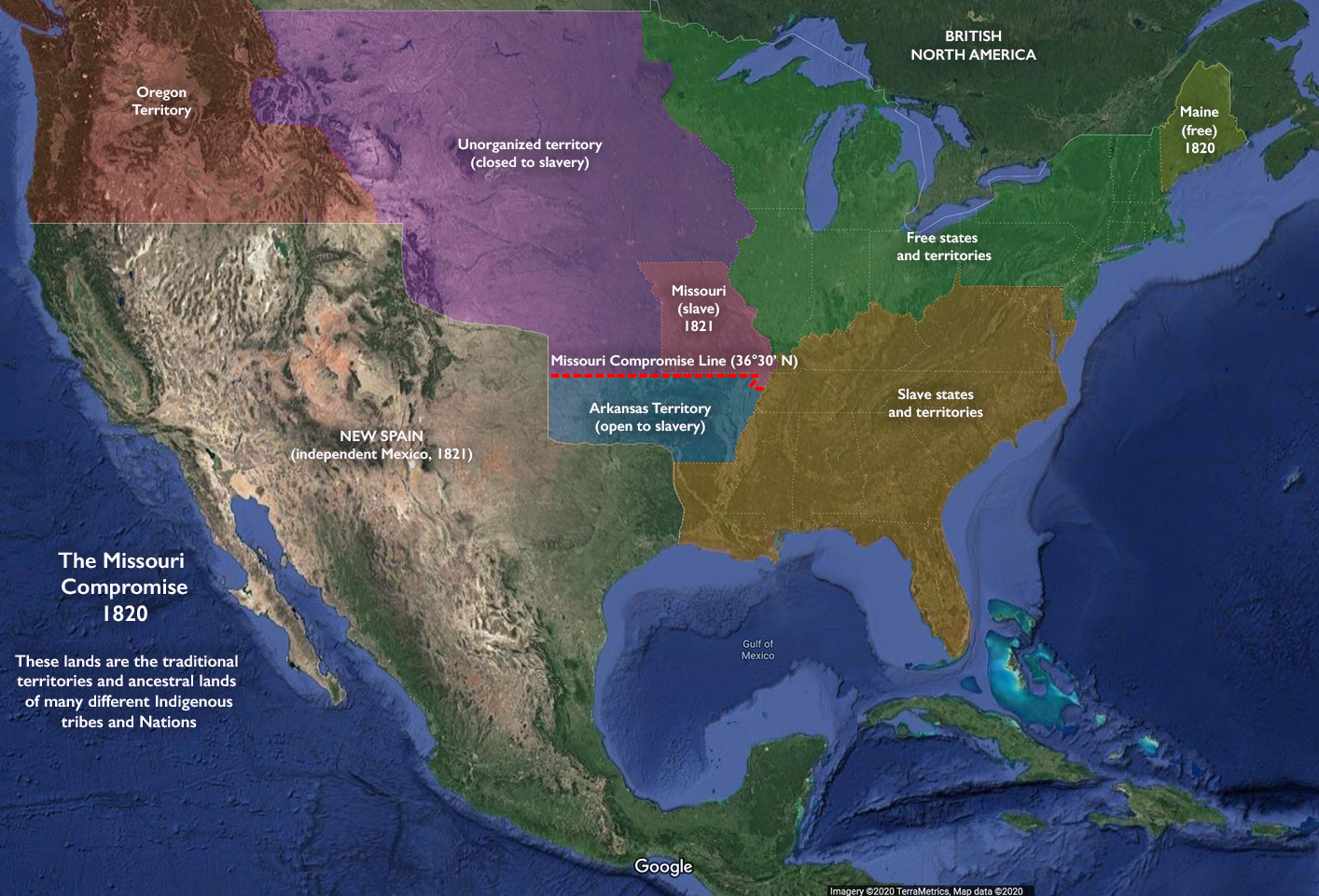

Map depicting U.S. states and territories in 1820. The Missouri Compromise admitted Maine as a free state, and then permitted Missouri to organize as a slave state, drawing a line across Missouri’s southern border above which slavery would not be permitted in the unorganized territory (underlying map © Google).

Finally, the Speaker of the House, Henry Clay, engineered the “Missouri Compromise”: Missouri would get its enabling act (which would allow it to become a state), without conditions restricting slavery; Maine would enter the union as a free state, while slavery would be banned in the rest of the Louisiana Purchase territory above the southern border of Missouri (at latitude 36°30’N). In March 1820, Congress consented to these terms, and Maine entered the union as a free state shortly thereafter.

But the controversy was not yet at an end. When Missouri submitted its new state constitution for Congressional approval later that year, northern restrictionists balked when they saw that—in addition to legalizing slavery “in perpetuity”—it included a statute banning any free people of color from entering or settling in the state. As free people of color had citizenship in several northern states, this statute violated the privileges and immunities clause of the Constitution. Henry Clay once again brokered a compromise, extracting an empty promise from the Missouri state legislature not to pass any laws that violated the privileges and immunities clause in exchange for ratification of its constitution. Missouri officially entered the union as a slave state in 1821.

The consequences of compromise

The Missouri Compromise avoided a national crisis, but it did nothing to resolve the problems that had caused it in the first place, which would resurface with a vengeance in the years leading up to the Civil War. The question of whether Congress should permit slavery not only to exist but to expand westward, further entrenching an institution bringing misery to millions of enslaved people, would continue to create sectional strife for another forty years.

George Caleb Bingham was a painter and a politician who served in the Missouri House of Representatives. Here, Bingham depicts a politician (right) speaking directly to the voters of Missouri in what appears to be an inn or tavern. In 1849, when this painting was completed, the issue of slavery once again convulsed the nation when the Wilmot Proviso, like the Tallmadge amendment, proposed a ban on slavery in future states formed out of any western lands the United States acquired. In 1847, Missouri had barred all free people of color from entering the state despite its 1821 promise to Congress, and so only white men are present to debate politics in this scene. Bingham himself endorsed overturning the Missouri Compromise and permitting residents of states to vote on whether to permit slavery. George Caleb Bingham, Country Politician, 1849, oil on canvas, 51.8 x 61cm (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco).

Despite its name, the Missouri Compromise (which ensured that Missouri could become a slave state—while slavery would be banned in the rest of the Louisiana Purchase territory above the southern border of Missouri) was a victory for slaveholders. For them, it confirmed the principle that slavery could expand into new states.

The Missouri Compromise was overturned (by the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act) before any free states could be formed out of the Louisiana Purchase territory earmarked for them. Then, in an effort to prevent any future efforts to limit slavery’s expansion, the slaveholder-dominated Supreme Court ruled the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional in 1857.

Appeasing slaveholders was a doomed enterprise, however. Slaveholding states seceded from the union in 1861, starting the Civil War, and ultimately brought about the end to slavery they had feared for so long.

Notes:

- Thomas Jefferson, in a letter to John Holmes, April 22, 1820.

- See Paul Finkelman, “The Appeasement of 1850,” in Paul Finkelman and Donald R. Kennon, eds., Congress and the Crisis of the 1850s (Ohio University Press, 2011), pp. 36–79.

- James Tallmadge Jr., speech to the House of Representatives, February 15, 1819.

- Jefferson, letter to John Holmes, April 22, 1820.

Additional resources:

A Founding Father on the Missouri Compromise, 1819

Missouri Controversy Documents, 1819-1920

James Monroe, Draft Letter on “Missouri Question”

Paul Finkelman and Donald R. Kennon, eds., Congress and the Emergence of Sectionalism: From the Missouri Compromise to the Age of Jackson (Ohio University Press, 2008).

Robert Pierce Forbes, The Missouri Compromise and its Aftermath: Slavery and the Meaning of America (University of North Carolina Press, 2009).

Sean Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln (W.W. Norton & Co., 2005).