Thomas Jefferson, Monticello, Charlottesville, Virginia, 1770–1806 (photo: Corkythehornetfan, CC BY-SA 3.0)

A gentleman architect

In an undated note, Thomas Jefferson left clear instructions about what he wanted engraved upon his burial marker:

Here was buried

Thomas Jefferson

Author of the Declaration of American Independence

of the Statute of Virginia for religious freedom

Father of the University of Virginia

Jefferson explained, “because by these, as testimonials that I have lived, I wish most to be remembered.” To be certain, there are important achievements Jefferson neglected. He was also the Governor of Virginia, American minister to France, the first Secretary of State, the third president of the United States, and one of the most accomplished gentleman architects in American history. To quote William Pierson, an architectural historian, “In spite of the fact that his training and resources were those of an amateur, he was able to perform with all the insight and boldness of a high professional.”

Indeed, even had he never entered political life, Jefferson would be remembered today as one of the earliest proponents of neoclassical architecture in the United States. Jefferson believed art was a powerful tool; it could elicit social change, could inspire the public to seek education, and could bring about a general sense of enlightenment for the American public. If Cicero believed that the goals of a skilled orator were to Teach, to Delight, and To Move, Jefferson believed that the scale and public nature of architecture could fulfill these same aspirations.

Thomas Jefferson, Monticello (view from the north), Charlottesville, Virginia, 1770–1806 (photo: William Avery Hudson, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Return to the classical

Jefferson arrived at the College of William and Mary in 1760 and took an immediate interest in the architecture of the college’s campus and of Williamsburg more broadly. A lifelong book lover, Jefferson began his architectural collection while a student. His first two purchases were James Leoni’s The Architecture of A. Palladio (1715–20) and James Gibbs’ Rules for Drawing the Several Parts of Architecture (1732).

Although never formally trained as an architect, Jefferson, both while a student and then later in life, expressed dissatisfaction with the architecture that surrounded him in Williamsburg, believing that the Wren-Baroque aesthetic common in colonial Virginia was too British for a North American audience. In an oft-quoted passage from Notes on Virginia (1782), Jefferson critically wrote of the architecture of Williamsburg:

“The College and Hospital are rude, mis-shapen piles, which, but that they have roofs, would be taken for brick-kilns. There are no other public buildings but churches and court-houses, in which no attempts are made at elegance.”

Thus, when Jefferson began to design his own home, he turned not to the architecture then in vogue around the Williamsburg area, but instead to the classically inspired architecture of Antonio Palladio and James Gibbs. Rather than place his plantation house along the bank of a river—as was the norm for Virginia’s landed gentry during the eighteenth century—Jefferson decided instead to place his home, which he named Monticello (Italian for “little mountain”) atop a solitary hill just outside Charlottesville, Virginia.

French Neo-Classicism for an American audience

Construction began in 1768 when the hilltop was first cleared and leveled, and Jefferson moved into the completed South Pavilion two years later. The early phase of Monticello’s construction was largely completed by 1771. Jefferson left both Monticello and the United States in 1784 when he accepted an appointment as America Minister to France. Over the next five years, that is, until September 1789 when Jefferson returned to the United States to serve as Secretary of State under newly elected President Washington, Jefferson had the opportunity to visit Classical and Neoclassical architecture in France.

Thomas Jefferson, Rotunda, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia, 1819–26 (photo: Michael Hebb, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

This time abroad had an enormous effect on Jefferson’s architectural designs. The Virginia State Capitol (1785–89) is a modified version of the Maison Carrée (16 B.C.E.), a Roman temple Jefferson saw during a visit to Nîmes, France. And although Jefferson never went so far as Rome, the influence that the Pantheon (125 C.E.) had over his Rotunda (begun 1817) at the University of Virginia is so evident it hardly need be mentioned.

Politics largely consumed Jefferson from his return to the United States until the last day of 1793 when he formally resigned from Washington’s cabinet. From this year until 1809, Jefferson diligently redesigned and rebuilt his home, creating in time one of the most recognized private homes in the history of the United States. In it, Jefferson fully integrated the ideals of French neoclassical architecture for an American audience.

In this later construction period, Jefferson fundamentally changed the proportions of Monticello. If the early construction gave the impression of a Palladian two-story pavilion, Jefferson’s later remodeling, based in part on the Hôtel de Salm (1782–87) in Paris, gives the impression of a symmetrical single-story brick home under an austere Doric entablature. The west garden façade—the view that is once again featured on the American nickel—shows Monticello’s most recognized architectural features. The two-column deep extended portico contains Doric columns that support a triangular pediment that is decorated by a semicircular window. Although the short octagonal drum and shallow dome provide Monticello a sense of verticality, the wooden balustrade that circles the roofline provides a powerful sense of horizontality. From the bottom of the building to its top, Monticello is a striking example of French Neoclassical architecture in the United States.

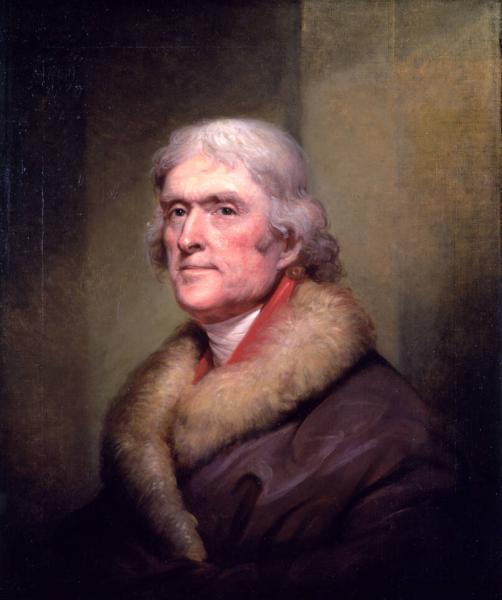

Rembrandt Peale, Thomas Jefferson, 1805, oil on linen, 28 x 23 1/2″ (New-York Historical Society)

Jefferson changed political parties and was a Democratic-Republican by the time he was elected president. He believed the young United States needed to forge a strong diplomatic relationship with France, a country Jefferson and his political brethren believed were our revolutionary brothers in arms. With this in mind, it is unsurprising that Jefferson designed his own home after the neoclassicism then popular in France, a mode of architecture that was distinct from the style then fashionable in Great Britain. This neoclassicism—with roots in the architecture of ancient Rome—was something Jefferson was able to visit while abroad.

Failing to live up to his own democratic ideals

By helping to introduce classical architecture to the United States, Jefferson intended to reinforce the ideals behind the classical past: democracy, education, rationality, civic responsibility. Because he detested the English, Jefferson continually rejected British architectural precedents for those from France. In doing so, Jefferson reinforced the symbolic nature of architecture. Jefferson did not just design a building; he designed a building that eloquently spoke to the democratic ideals of the United States. This is clearly seen in the Virginia State Capitol, in the Rotunda at the University of Virginia, and especially in his own home, Monticello.

In many regards, Thomas Jefferson remains an exceedingly complicated historical figure. On the one hand, we can justifiably laud his significant civic and architectural achievements, for his accomplishments in the political realm are unmatched in American history and the buildings he designed—Monticello, the Virginia State Capitol, and the Rotunda at the University of Virginia—places him at the forefront of the gentlemen architects of the early Federal period. Yet on the other hand, we need to wrestle with the truth that Jefferson was—as were the majority of the Founding Fathers from the southern colonies, men such as George Washington, James Madison, and James Monroe—a slaveholder who owned more than 600 men, women, and children during the course of his life.

So when we look at Monticello—a building in part constructed by the enslaved people Jefferson owned—we are right to feel a kind of conflict. Although he helped to introduce classical architecture to the United States and used architectural language to reinforce the ideals behind the classical past—elements such as democracy, education, rationality, civic responsibility—those very virtues were actively denied to many. Because Jefferson so detested the English, he continually rejected British architectural precedents for those from France. In doing so, Jefferson reinforced the symbolic nature of architecture. Jefferson did not just design a building; he designed a building that eloquently spoke to the democratic ideals the United States should aspire to, even if in practice these democratic ideals were intentionally withheld from the enslaved people Jefferson owned.

Additional resources

Monticello and the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, UNESCO

Monticello Explorer (click ‘text-based version of the site’)