Stonehenge: how, and why, did prehistoric people build it?

Read Now >Chapter

Permanence, Portability, and Power in the Northern Seas, c. 700–1200

An enormous, unrefined slab of stone decorated with carvings that were once brightly painted remains in Jelling, Denmark to this day. Erected around 965 by King Harald Bluetooth, the stone was placed beside an earlier monument, sponsored by Harald’s father, Gorm, to honor his wife, Thyra. King Bluetooth’s stone is decorated with carvings of ancient runes that acknowledge his parentage and tie him to the centuries-old practice of erecting such monuments throughout the landscape. One side of the stone depicts a mythical creature, known as the “Great Beast,” demonstrating Harald’s ability to harness pre-Christian sources of power. The tenth-century king had recently united Denmark and Norway with his military might, and he wanted to add a new layer to this visualization of his increasing power: an image of the crucified Christ (shown below).

Map with areas of the northern seas (underlying map © Google)

The world that Harald Bluetooth inhabited was characterized by cultural exchange, mainly conducted along the waterways of the Northern Seas. From Scandinavia to the west of Ireland, expert shipbuilders crafted vessels that were able to sail all the way across the Atlantic Ocean. [1] But Harald’s world was also filled with conflict. Local leaders and regional kings were constantly vying for position, and consolidating power where they could. Religious practices were also in flux, as Christian practices began to intersect with pre-Christian traditions and beliefs in the tenth century.

For a leader in such times, colorful, decorated standing stones served to permanently and publicly declare his ability to harness all sorts of power, both ancestral and contemporary, pre-Christian and Christian. The king and his entourage would also parade portable symbols of wealth and finery throughout the countryside. We can imagine Harald and his entourage wearing fine silver brooches, finger rings, and arm bands, and carrying elaborately decorated weaponry. Even their horses would have been adorned with precious metal fittings.

This chapter considers how powerful warrior kings like Harald Bluetooth, as well as devoted followers of Christ, demonstrated their political and holy power with both permanent and portable visual objects. This period in European history (c. 700–1200) includes so many diverse cultures—Angles, Saxons, Danes, Jutes, and more—that it is challenging to give it an appropriately inclusive name. Many of the modern labels used to classify these cultures are inaccurate and even carry negative associations. The phrase “Anglo-Saxon,” for example, has a long history of misuse, especially in white supremacist contexts, as Dr. Mary Rambaran-Olm discusses in her essay “Misnaming the Medieval: Rejecting Anglo-Saxon Studies.” [2] In an effort to mitigate the damage caused by this language, I have avoided the terms “Anglo-Saxon” and “Viking” as ethnic descriptors.

What is most important to understand about the term “Viking” is that it describes an activity, a way of life, not an ethnicity. The phrase “the Viking Age,” as it is used here on Smarthistory, makes sense because, in the years between about 700 and 1200 of the common era, Scandinavians went viking—seafaring, adventuring, raiding. Throughout the Northern Seas and beyond, they came into contact with others whose kings erected colorful standing stones, and even crosses, and they saw portable signs of power: valuable, golden objects, belonging to both kings and to the Church. Ultimately, most modern terminology about this time in Europe is flawed, but the surviving visual objects tell a rich story about the people and their beliefs. Read on to learn how such very different works of art—enormous, immovable stone sculptures and small-scale, mobile treasures—conveyed many forms of power. For everyone from warrior kings to devout holy figures, spheres of influence and control could be pinpointed, advertised, and extended by means of visual imagery.

Prehistoric Megaliths and Ancient Treasures

Stonehenge, Salisbury Plain, Wiltshire, England, c. 2550–1600 B.C.E., circle 97 feet in diameter, trilithons: 24 feet high (photo: Maedin Tureaud, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The practice of erecting large standing stones (megaliths) in the Northern Seas region began long before 700 C.E. Prehistoric stone circles like Stonehenge still survive throughout the landscape, and scholars believe that these imposing constructions were built on land that was considered sacred. The mystical powers circulating at such locations would extend beyond the stones themselves, available for both kings and holy men to harness for worldly purposes. Early medieval viewers must have sensed the eternal presence of their ancestral traditions in these enormous stones.

Poulnabrone Dolmen, c. 4200–2900 B.C.E., The Burren, County Clare, Ireland (photo: Sabine Holzmann, CC BY-SA 3.0)

For example, in Ireland, huge dolmens marked sacred places and may have been associated with burial and the veil between the living and the dead.

Ring of Brogdar, Neolithic period, Ornkey, Scotland, 104 meters in diameter (photo: Accuruss, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Off the coast of Scotland, the Ring of Brodgar adorned the landscape near the village at Skara Brae in the Orkney archipelago, and megalithic stone circles have also been found throughout Ireland, England, Wales, Norway, Sweden, and Denmark.

Golden lunula and two gold discs (from the Coggalbeg hoard), c. 2300–2000 B.C.E., gold, Coggalbeg, County Roscommon, Ireland (National Museum of Ireland, Archaeology)

Precious golden and silver objects had also been crafted throughout the region for millennia, as demonstrated by such finds as the Coggalbeg and Broighter Hoards. Since at least the Neolithic era, evidence shows that powerful people across the Northern Seas were adorning themselves with portable signs of their wealth and status. Over many centuries, they perfected the crafts of metalworking, inlay, and cloisonné enameling, and they created stunning jewelry, weapons, chalices, and reliquaries. In addition to these valuable personal items, the power of words—even the sacred Christian Word—was portable, in the form of illuminated manuscripts.

Watch videos and read essays about prehistoric megaliths and ancient treasures

Orkney: The monuments here give a graphic depiction of life in this remote archipelago in the far north of Scotland some 5,000 years ago.

Read Now >

Golden lunula and two gold discs (Coggalbeg hoard): This thin crescent-shaped piece of gold, along with two discs, indicates Ireland’s early sophisticated metal-working and how travel and trade were prevalent even in the Bronze Age.

Read Now >/3 Completed

Permanence: Monumental Crosses and Rune Stones

Muiredach’s High Cross (South Cross), former Monastery of Monasterboice (Mainistir Bhuithe), County Louth, Ireland, sandstone, 5.2 m high (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The introduction of Christian practices into the region—first in Ireland around the 5th century—affected the form, style, and function of megalithic sculpture. In England, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales, sculptors began to erect monumental ringed crosses carved with intricate designs and figural imagery. By the 10th century, as Christianity began to take hold in Scandinavia, standing stones were decorated with interlace designs and symbols depicting pre-Christian and Christian elements side by side. All of these stone sculptures were originally painted in bright colors, to draw attention to the imagery and pick out details in the designs.

Detail of the Crucifixion. Muiredach’s High Cross (South Cross), former Monastery of Monasterboice (Mainistir Bhuithe), County Louth, Ireland, sandstone, 5.2 m high (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The ringed crosses were emphatically Christian monuments. Scholars believe that wooden crosses were built first, at least in Ireland, possibly as early as 600 C.E. Those wooden structures were eventually replaced by carved stone crosses, hundreds of which still remain in their original locations. The crosses in Ireland are perhaps the best known, but there are similar monuments from the same time period surviving in England, Scotland, and Wales.

Left: Cross of the Scriptures, 9th century, Clonmacnoise monastery, founded 544 by St Ciarán, County Offaly (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: detail of an east face base panel showing an image of a king and a representative of the church collaborating (inscription: “a prayer for Colman who erected this cross for King Flann”), original created in 9th c. (replica placed in the location of the original), Clonmacnoise, County Offaly (photo: Keith Ewing, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Most of the crosses are carved with scenes from the Bible and the Lives of the Saints, as well as intricate geometric designs. They were erected to mark sacred places in the landscape, and some may have included visual reinforcements for real-world power structures. Visible from a great distance, the crosses could indicate the location of a sacred monastery and the Christian ownership of the land, while the relief decorations could signal earthly power structures. At Clonmacnoise, for example, an image of a king and a representative of the church (identified by their costumes) collaborating emphasizes the interconnectedness of the civic and religious realms. [3]

In Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, large stones carved with geometric designs and runic letters appear around the 10th century C.E. Taking their name from the runic letters inscribed into the stones, these “Rune Stones” retained the natural shape of the rock, but their surfaces were decorated with brightly painted relief decorations. Some of the stones also include explicitly Christian imagery, such as King Harald Bluetooth’s monument (described above).

Despite the popularity of large stone monuments, surviving stone buildings are less common throughout the region. Wood appears to have been a more popular material for church building, and it is likely that many early wooden structures simply did not survive. In Scandinavia, wooden Stave Churches have been dated to the 12th century, and many archaeological excavations have included evidence of postholes for wooden structures.

Skellig Michael monastery (Ireland), 6th–13th centuries (most of the stone construction dates to 8th–11th centuries) (photo: Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Small stone buildings survive in some locations, and larger, more complex stone buildings were constructed in the later Middle Ages. On the remote island of Skellig Michael, for instance, early medieval stone huts tell the story of isolated hermits and monks, religious people who left society to pray, study, and meditate.

Watch videos and read essays about monumental crosses and rune stones

Muiredach Cross: Originally painted, monumental crosses in Ireland like this one are the largest freestanding sculpture from the Middle Ages.

Read Now >

Clonmacnoise: an important monastery that attracted religious pilgrims and royal patronage, is considered a quintessential example of the early Irish church.

Read Now >

Urnes Stave Church: The wooden church was built in the 12th and 13th centuries and is an outstanding example of traditional Scandinavian wooden architecture.

Read Now >

Skellig Michael: This dramatic island off the coast of Ireland was once a place for monks to remove themselves from the world.

Read Now >/5 Completed

Portability: Power in Motion

Merovingian (Frankish) Looped Fibulae, mid-6th century, silver gilt worked in filigree with inlaid garnet and other stones (Musée des Antiquities Nationales, Saint-Germain-en-Laye)

While permanent stone monuments were being erected to mark sacred and political territories, small-scale, precious objects were also circulating throughout the region. These valuable items could easily demonstrate their owners’ wealth and prominence, and that display of status could act as reminder of dominance and control, both for sacred leaders and for warrior kings.

In the Northern Seas region and beyond, fibulae and other types of brooches had been status symbols for centuries. Made from precious metals like gold and silver and adorned with imported gemstones like garnets, these personal items were both materially valuable and socially significant.

Left: Small selection of objects from the Viking-age Galloway Hoard, which includes more than 100 objects made in gold, silver, crystal, glass, stone, and earthen objects, discovered in the historical county of Kirkcudbrightshire in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland in 2014 (National Museum of Scotland, CC BY-SA 4.0); right: Cuff from the Staffordshire Hoard, which includes more than 4,500 items a and metal fragments, found near the village of Hammerwich, near Lichfield, in Staffordshire, England in 2009, c. 600–900 C .E. (Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, photo: Daniel Buxton, CC BY 2.0)

Most of what modern scholars have learned about these precious objects comes from the field of archaeology. Frequently, a collection of precious items is found buried together in what’s known as a hoard, or they might be found in an elite person’s burial. Many of these hoards appear to have been buried quickly, in times of crisis, and it is difficult to determine precisely when or why they were placed in the ground. It is also rare to be able to associate a collection of objects with specific owners or craftspeople. What we can say with certainty about these hoards of precious objects, though, is that they signify both wealth and status. The fact that such valuable items were rapidly collected and hidden underground suggests conflict, and reinforces the idea that the items contained in the hoard were the target of an attack, an effort to confiscate wealth and transfer both its economic and its symbolic power. Hoards continue to be unearthed, including these discovered within the last few decades, such as the Staffordshire Hoard and the Galloway Hoard.

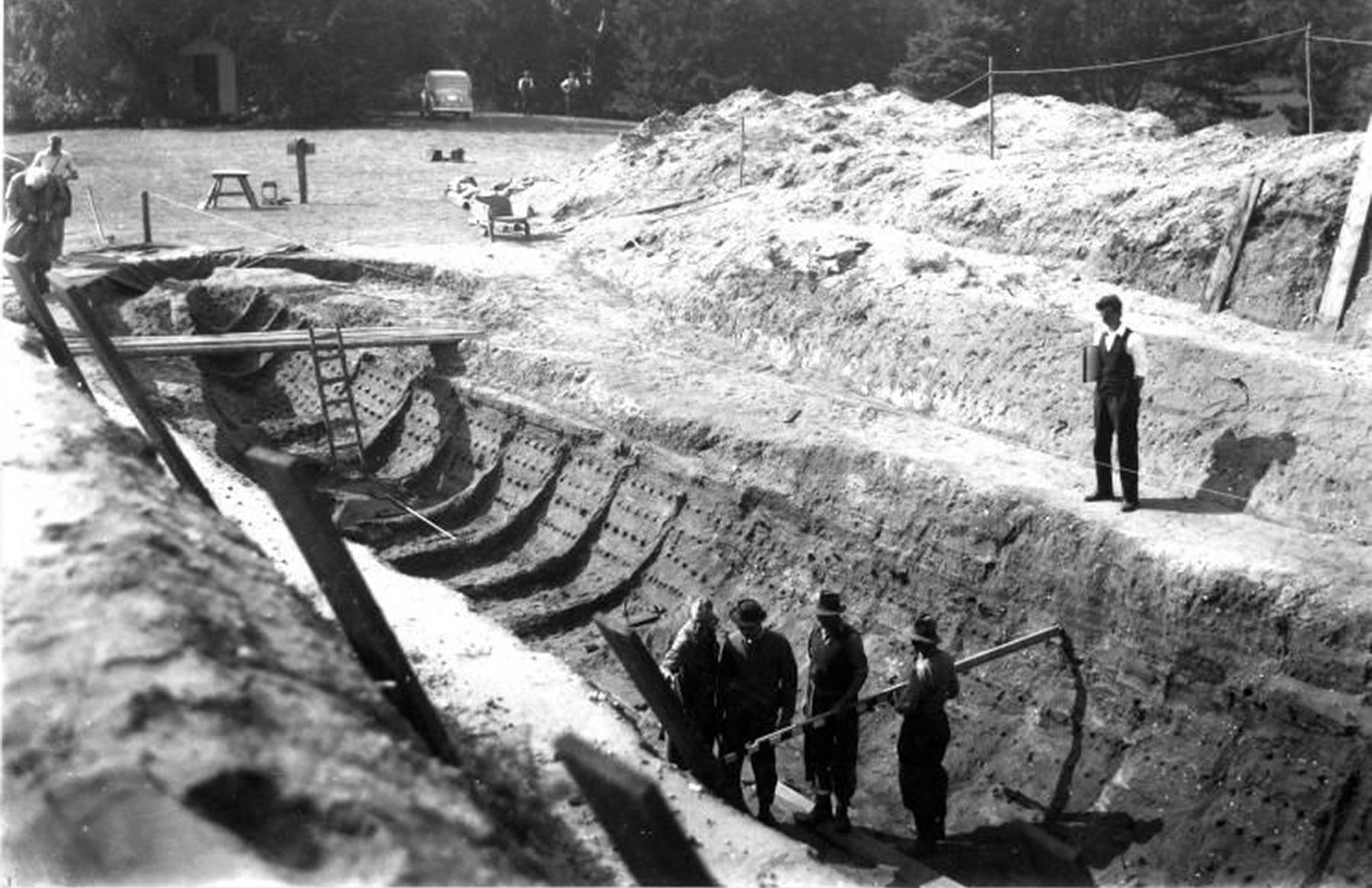

Photo of the excavation of the Sutton Hoo ship burial, by Barbara Wagstaff, 1939 (© 2019 The Trustees of the British Museum)

Portable precious items have also been recovered as grave goods in elite burials, another example of pre-Christian and Christian practices appearing alongside one another in the early medieval Northern Seas. The maritime culture in the area meant that powerful rulers—both male and female—were often buried with their ships.

The Sutton Hoo helmet, early 7th century, iron and tinned copper alloy helmet, consisting of many pieces of iron, now built into a reconstruction, 31.8 x 21.5 cm (as restored) (The British Museum) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

These ship burials compound the idea of portable power by combining a person’s mortal remains with the precious items that articulated their earthly status or military strength. Their status travels with them into the afterlife, as demonstrated by their brooches, necklaces, bracelets, decorated weaponry, and elaborate helmets.

The Ardagh Chalice, c. 8th century, silver, gilt copper, gold filigree, gold, gilt bronze, silver, polychrome glass, amber, rock crystal, 18 cm high, 19.5 cm in diameter at the rim, found in a hoard in the ringfort of Reerasta, near Ardagh, County Limerick, Ireland (National Museum of Ireland)

In addition to secular objects like brooches and helmets, artists in this period made elaborately decorated precious items for use in Christian rites and rituals. Such objects include processional crosses, patens and chalices to celebrate the mass, as well as sacred reliquaries. A reliquary is a precious container for the holy relic of a saint. Priests—and sometimes kings—would carry these golden and gem-encrusted objects in church processions or through the town on a holy day, and sacred energy was believed to emanate from the object, blessing the people and reinforcing either sacred or secular leadership, sometimes both.

The Cross of Cong (commissioned by Toirrdelbach Ua Conchobair king of Connacht and high king of Ireland), 1123, oak core within cast bronze, rock crystal, gold filigree, gilding, silver sheeting, niello and silver inlay, glass, and enamel, 76 x 48 x 3.5 cm (National Museum of Ireland; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-2.0)

In 1123, for example, the Irish Cross of Cong was carried in procession to demonstrate king Toirrdelbach Ua Conchobair’s status and to reinforce his authority. The gold and enamel cross was known to contain a holy relic—a sliver of the True Cross (the cross Jesus was crucified on). The stunning exterior of the reliquary cross would have enhanced the aura of the relic within, and carrying it in procession would have been like a performance of power for the king and the church leaders.

Saint Patrick’s Bell and Shrine; bell: 8th–9th century C.E., iron; shrine: c. 1100 C.E., copper-alloy box, silver gilt, gold, silver, gilt-copper, rock crystal, colored stones, 26.7 x 15.5 cm (National Museum of Ireland, Dublin)

The fine, elaborately decorated exteriors of reliquaries showed the community that the Church had valuable resources and also that the holy leaders had the power to contain the sacred energy itself, which came in the form of the relic within. Another wonderful early medieval Irish reliquary adds a dimension of imagined sound to the picture. Enclosed in a decorated shrine, Saint Patrick’s bell remains silenced, but the outer form of the reliquary reminds viewers that the bell is meant to ring, and that the related sacred power has the potential to travel great distances via sound waves.

Watch videos and read essays about portable objects and power in motion

Brooch from Chessell Down: Masks and scrolls adorn the square head of this silver-gilt brooch.

Read Now >

Sutton Hoo Ship Burial: 1,400 years ago, people hauled a ship up a hilltop and buried their king and his treasure within.

Read Now >

The Sutton Hoo purse lid: Rendered in gold and garnet, the enigmatic animals on this purse lid stand out above white bone.

Read Now >

The Sutton Hoo helmet: Restored, dismantled, and restored again, this helmet was a pile of rusted iron and tinned bronze when first discovered.

Read Now >

The Oseberg Ship: A spectacular oak longship—found within a burial mound—is one of the most studied works of the period.

Read Now >

Saint Patrick’s Bell and Shrine: This bell and shrine are associated with the founder of Christianity in Ireland.

Read Now >/9 Completed

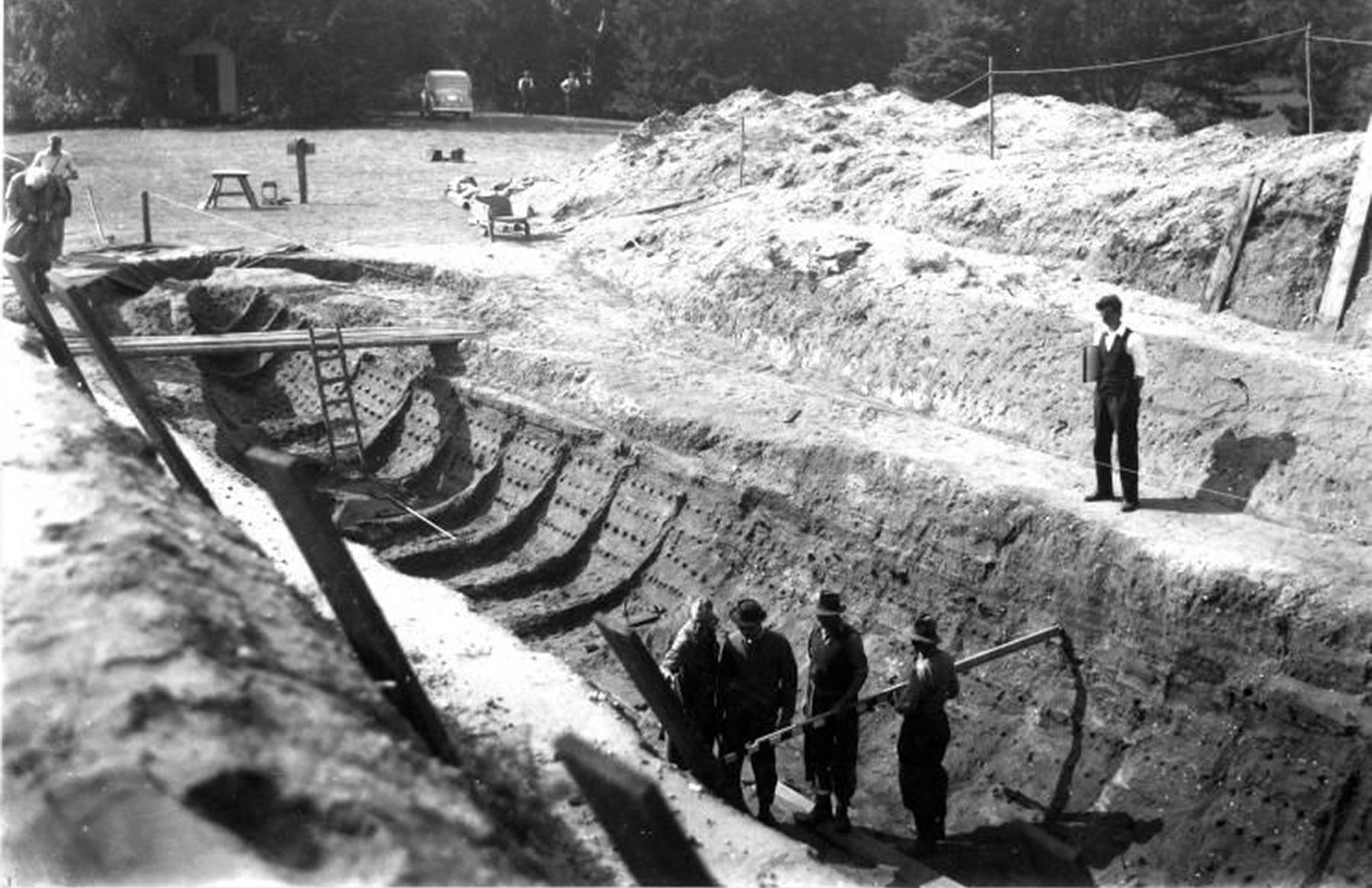

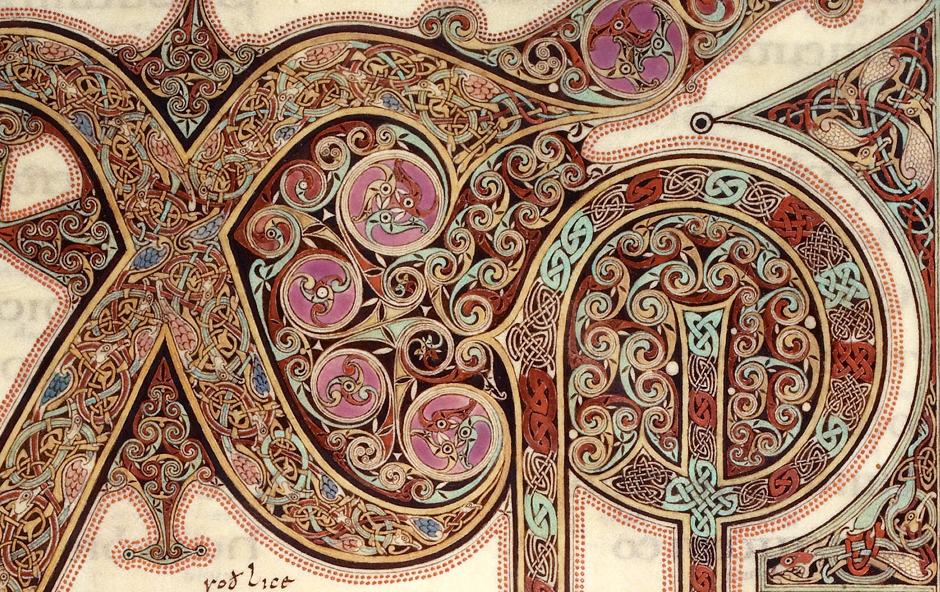

The Lindisfarne Gospels, c. 700, parchment, 36.5 x 27.5 cm (The British Library)

The power of books

Books were another type of sacred, portable item that conveyed both holy and royal power. Christian books were especially precious, both because the Bible specifically proclaims that its words contain holy power and because making manuscripts was a costly and labor-intensive process. Some books were encased in precious reliquaries, while others simply conveyed power by their very existence.

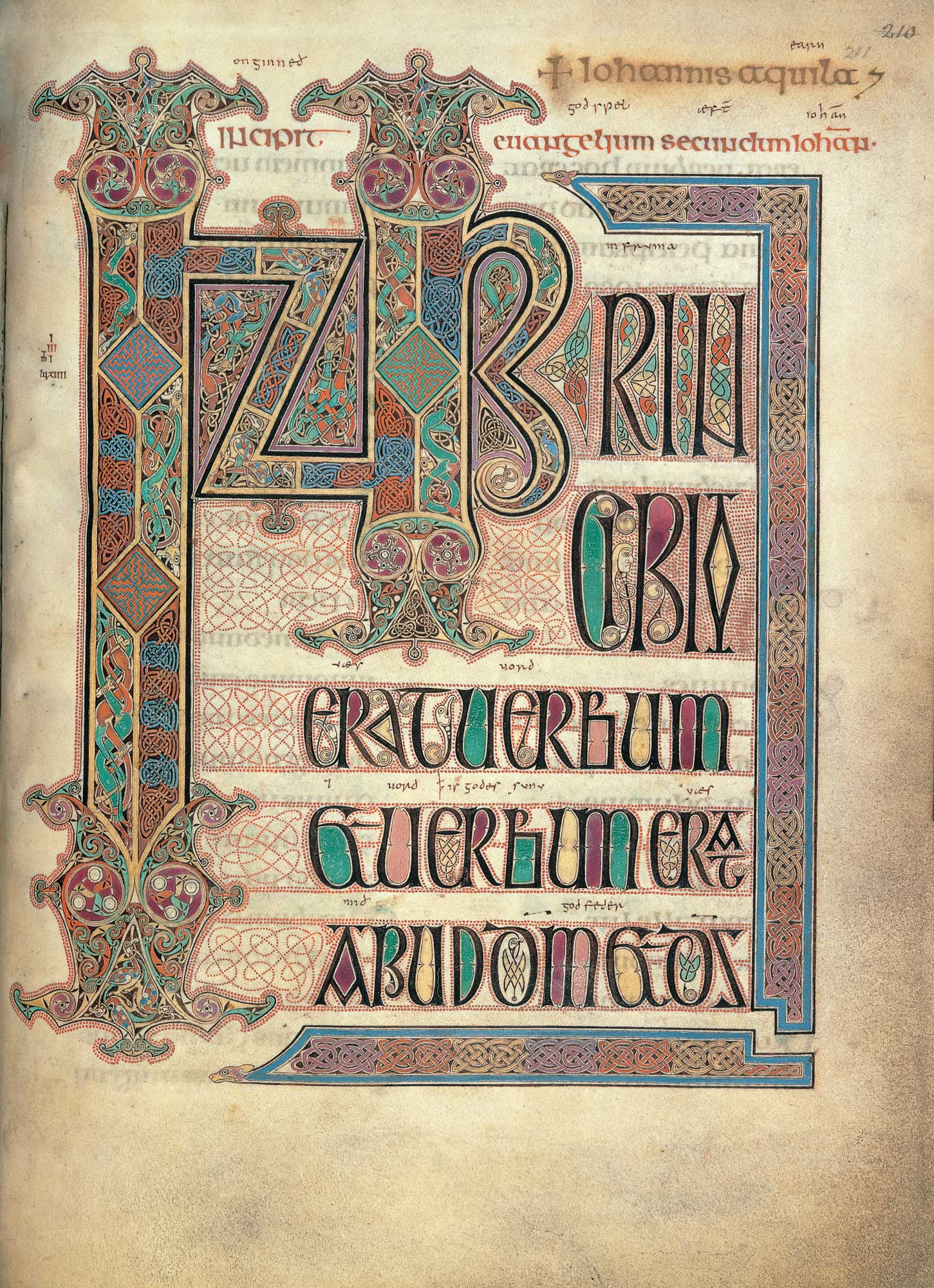

Chi Rho page, Book of Kells, c. 800, 340 vellum folios, 33.0 x 25.5 cm each (edges trimmed and gilded in the 19th century), MS 58 (Trinity College Library, Dublin)

The power of books in the early medieval period is perhaps best illustrated by the Book of Kells (c. 800 C.E.). Now in Dublin, the manuscript is notorious for its travels. In fact, scholars have spent decades trying to trace its journey from Iona in Scotland to Kells in Ireland. Over the centuries, the book has only increased its powerful aura, becoming a symbol of ethnicity and Irish nationalism in addition to a sacred text.

Watch videos and read essays about the power of books

The Lindisfarne Gospels: The “cross-carpet” pages of this early 8th-century manuscript weave together birds, knots, spirals—and the Cross.

Read Now >

Symbolism in the Book of Kells: Snakes, peacocks, lions, hares, mice, and more—what does it all mean?

Read Now >/4 Completed

The cultures that thrived throughout the Northern Seas region in the early medieval period had long histories of constructing both massive stone monuments and painstakingly crafted objects made from precious materials. Brightly painted ringed crosses and rune stones alike stood throughout the landscapes of Ireland, England, Scotland, Wales, Denmark, Norway, and Sweden in this period, emphasizing the connections between spheres of political and religious control. As people moved through the countryside and along the many waterways, they wore, wielded, and displayed precious items whose mystical auras generated zones of power. Modern scholars have discovered mysteriously buried hoards and elite grave goods throughout the area, and elegant illuminated manuscripts, such as the Book of Kells, continue to announce the artistic power of these cultures to this day.

Notes:

[1] There are Viking settlements in Newfoundland that have been dated to c. 1021.

[2] See Mary Rambaran-Olm, “Misnaming the Medieval: Rejecting Anglo-Saxon Studies,” History Workshop (November 2019; accessed 10 December 2022).

[3] For more on the differences in costume, see Maggie M. Williams, “Warrior Kings and Savvy Abbots: The Cross of the Scriptures, Clonmacnois,” in The World of Villard de Honnecourt: The Best of Avista Forum Journal (Brill, forthcoming); originally appeared in Avista Forum Journal: Journal of the Association Villard de Honnecourt for the Interdisciplinary Study of Medieval Technology, Science, and Art 12, no. 1 (Fall 1999): pp. 4–11.

Key questions to guide your reading

How do works of art communicate power for the people who make, view, use, or wear them?

What kinds of power did early medieval objects signify? Political? Religious? Social? Economic?

What kind of power does a permanent, monumental structure convey? What about a materially valuable object that can be worn, carried, or displayed?

Jump down to Terms to KnowHow do works of art communicate power for the people who make, view, use, or wear them?

What kinds of power did early medieval objects signify? Political? Religious? Social? Economic?

What kind of power does a permanent, monumental structure convey? What about a materially valuable object that can be worn, carried, or displayed?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

Chalice

Cloisonné enameling

Dolmen

Fibula (pl. fibulae)

High Cross

Hoard

Illuminated manuscript

Interlace

Megalith

Paten

Relic

Reliquary

Rune Stones

Stave churches

Viking Age

Learn more

Learn more about the Jelling stones from UNESCO and the National Museum in Denmark.

For more on the materials and techniques used in making these objects, and to locate the early medieval period in the Northern Seas, see these essays for context:

- Medieval Goldsmiths

- Making Manuscripts

- Introduction to the Middle Ages

- A new pictorial language: the image in medieval art

- “Anglo-Saxon” England

For more on hoards discovered in the past few decades, see:

Howard Williams, Joanne Kirton, & Meggen Gondek, eds., Early Medieval Stone Monuments: Materiality, Biography, Landscape (Boydell & Brewer, 2015).

Karen Overbey, Sacral Geographies: Saints, Shrines, and Territory in Medieval Ireland (Brepols, 2012).

Maggie M. Williams, “ ‘Celtic’ Crosses and the Myth of Whiteness,” in A. Albin, M. Erler, T. O’Donnell, N. Paul, and N. Rowe, eds., Whose Middle Ages? Teachable Moments for an Ill-Used Past (Fordham University Press, 2019), pp. 220–232. [Companion website here]

Maggie M. Williams, Icons of Irishness from the Middle Ages to the Modern World (NY: Palgrave Macmillan Press, The New MiddleAges Series, 2012).

Maggie M. Williams, “Warrior Kings and Savvy Abbots: The Cross of the Scriptures, Clonmacnois,” in The World of Villard de Honnecourt: The Best of Avista Forum Journal (Brill, forthcoming). Originally published in Avista Forum Journal: Journal of the Association Villard de Honnecourt for the Interdisciplinary Study of Medieval Technology, Science, and Art 12, no. 1 (Fall 1999): pp. 4–11.