Classic, classical, and classicism explained: What do we mean when we use these terms?

Read Now >Chapter 16

War, democracy, and art in ancient Greece, c. 490–350 B.C.E.

Iktinos and Kallikrates, The Parthenon, Athens, 447 – 432 B.C.E. (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The art and architecture of Classical Greece (c. 490–323 B.C.E.) has had an outsized impact in the history of art. It was revered and emulated in later periods and places such as Hellenistic Pergamon, Augustan Rome, and renaissance Italy. Writing in the eighteenth century, Johann Joachim Winckelmann deemed classical Greek art the pinnacle of all artistic achievement, a reputation that heavily influenced the development of the field of art history and has lingered into the twenty-first century. Classical art has been regularly praised for its stylistic elements, including notably its idealized depictions of the human form. These sculptures’ depictions of the human body appear naturalistic, depicting what humans actually look like, but it is a constructed naturalism without flaws or acknowledgment of reality. The artworks promote the idea that that which is most perfect is the most beautiful, and have been admired by generations of art historians and the general public alike.

Phidias (?), Sculpture from the east pediment of the Parthenon, marble, c. 448–432 B.C.E. (British Museum, London)

The term “classical” has become a synonym for an artistic form, visual, musical, or textual, that is both traditional and exemplary, such as classical ballet or classical music. The academic field that studies ancient Greek and Roman antiquity, primarily its texts, has long been known as the field of Classics. This chapter aims to go beyond the established stylistic reputation of classical art and examine it within its original historical context, providing a deeper understanding of the goals and meanings of the idealized art of the classical period.

Ancient Greek world map (underlying map © Google)

This chapter examines classical art and architecture, incorporating the periods and styles now known as Early Classical/ Severe (c. 490–450 B.C.E.), High Classical (c. 450–400 B.C.E.), and Late Classical (c. 400–323 B.C.E.). To highlight how the historical events of the era affected the development of artistic style and subject, the chapter is organized primarily chronologically, and examines art within its original context as a lens through which to examine the time period and culture in which it was produced.

Watch a video that introduces the classical

/1 Completed

Greco-Persian Wars

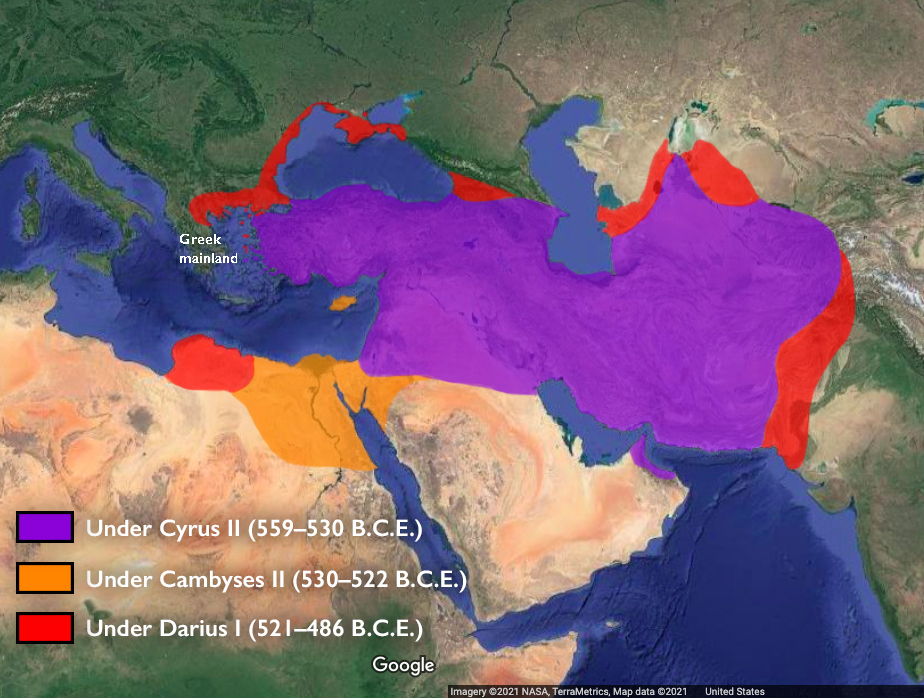

Growth of the Achaemenid Empire under different kings (underlying map © Google)

In 490 B.C.E., the Achaemenid Persian Empire, under the leadership of king Darius, invaded mainland Greece. The Persian Empire, stretching from the Mediterranean to central Asia, was the dominant political and military force in the region. Greece, by comparison, consisted primarily of independent city-states (poleis) and had little political or military power. Many Greeks, in the face of this unprecedented threat, temporarily put aside their own differences to form a unified military force. Against the odds, the Greeks won, with a decisive victory at the Battle of Marathon. Under a new king, Xerxes, the Persians invaded again in 480, and the Greeks, who had spent ten years building up their military forces and defenses, joined together and again won a series of battles. While for the Persians these were simply setbacks in their quest for territorial expansion and received little attention in their histories or art, for the Greeks, the Greco-Persian Wars were defining events, causing changes in Greek art, culture, and society. The Greeks now saw themselves as powerful players on the international stage, and this affected both their internal perceptions and their interactions with other societies. Their victories over the Persians were commemorated in various forms for the rest of the century, and especially in Athens, were regularly cast as triumphs of Greek civilization over the non-Greek barbarian other.

Read an essay about the Achaemenid Persian Empire

/1 Completed

The Severe Style: a period of change

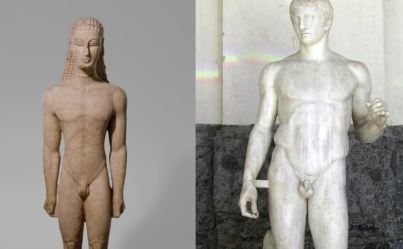

The Greco-Persian Wars led to changes in art that ushered in the classical style. Following the first Persian invasion in 490, the severe (or early classical) style emerged, which departed from the earlier archaic style.

Striding God (Artemision Zeus) (detail), c. 460 B.C.E., bronze, 2.09 m high, Early Classical (Severe Style), recovered from a shipwreck off Cape Artemision, Greece in 1928 (National Archaeological Museum, Athens)

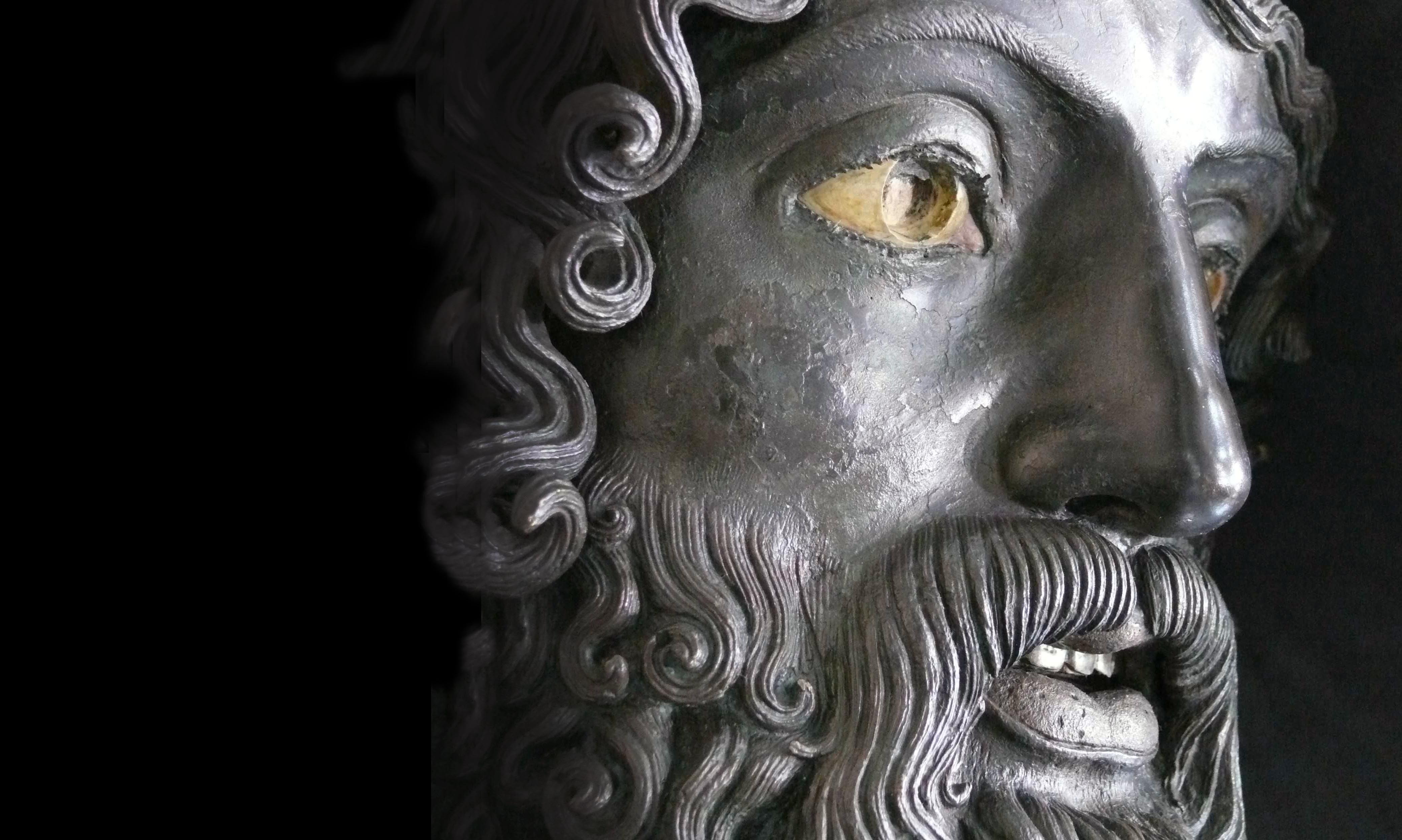

The Severe period derives its name from the so-called severe facial expressions on sculptures like the Striding God (Artemision Zeus) that contrast with earlier statues like the Anavysos Kouros and Peplos Kore with their archaic smiles.

Kritios Boy, after 480, marble, 86 cm high (Acropolis Museum)

On statues like the Kritios Boy and the Riace Warriors we notice a new pose, frequently referred to by the Italian term, contrapposto, which depicts the body in an S-curve position. Contrasting to standing kouroi of the sixth century, the new pose is seen by art historians to be more naturalistic as it mimics how people commonly stand with their weight resting on one leg.

Paris (?), from the west pediment from the Temple of Aphaia, Aegina, Archaic/Early Classical Periods, c. 490–480 B.C.E. (Glyptothek, Munich; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The emergence of the Severe style, while it seems to be linked with changes in Greek perceptions that followed the Greco-Persian Wars, was not an immediate revolution. This can be seen at the Temple of Aphaia on the island of Aegina. Like many Greek temples, it featured sculpture in its pediments that was mythological in subject. The pediments at Aegina are unusual, however, because they display multiple artistic styles: the sixth-century archaic style in the west pediment and the fifth-century severe style in the east. The date of the temple has been frequently debated due to these differences in style.

Some scholars have argued that the temple was begun before the Persian Wars when the archaic style was dominant and finished later once the Severe style came into vogue. More recently, other writers have posited that both pediments were done after 490 B.C.E., and that they are evidence that the archaic style continued to co-exist with the severe style for some time, with different artists employing different styles. This argument that the two styles co-existed pushes back against the theory that the Greco-Persian Wars and the associated changes in Greek self-perception led to immediate and comprehensive changes in artistic style. If this is correct, the classical style is less a revolution, as it is sometimes been called in art historical scholarship, and more an evolution. The Aegina pediments speak to how the development of style in the Greek world is still a debated topic, and that it was both gradual and messy.

Watch videos and read essays about the Severe Style

Kritios Boy: Following war with the Persians, this highly naturalistic sculpture was buried out of respect.

Read Now >

Striding God (Artemision Zeus): This bronze god sank to the bottom of the sea where he sat for millennia, but who is he and what can he tell us?

Read Now >

Riace Warriors: Archaeologists pulled these bronze warriors from the sea in 1972, but their origin and date remain a mystery.

Read Now >

East and West Pediments from the Temple of Aphaia, Aegina: Two different styles in two groups from the same temple—what does it mean?

Read Now >/5 Completed

Athens and the Athenian Democracy

The Acropolis of Athens viewed from the Hill of the Muses (photo: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The city of Athens saw dramatic political as well as artistic changes following the Greco-Persian Wars and played an important role in the development of the High Classical style that emerged in the mid-fifth century. Many art historical surveys of classical Greek art focus on Athens almost exclusively. Yet, Athens was only one among a number of Greek cities creating art and architecture in the period. This narrow focus in modern texts can be partly explained by Athens’ position as one of the wealthiest and most powerful cities in the Greek world in this period, and the comparatively large investments they made in the arts. To paraphrase the ancient historian Thucydides, Athens, through its investment in art and architecture, looked like a more powerful city than it actually was, while the modest appearance of its rival, Sparta, belied its own power (1.10).

Thucydides on Athens

For I suppose if Lacedaemon were to become desolate, and the temples and the foundations of the public buildings were left, that as time went on there would be a strong disposition with posterity to refuse to accept her fame as a true exponent of her power. And yet they occupy two-fifths of Peloponnese and lead the whole, not to speak of their numerous allies without. Still, as the city is neither built in a compact form nor adorned with magnificent temples and public edifices, but composed of villages after the old fashion of Hellas, there would be an impression of inadequacy. Whereas, if Athens were to suffer the same misfortune, I suppose that any inference from the appearance presented to the eye would make her power to have been twice as great as it is. We have therefore no right to be sceptical, nor to content ourselves with an inspection of a town to the exclusion of a consideration of its power.

Thucydides, The History of the Peloponnesian War, 1.10, translated by Richard Crawley, written 431 B.C.E.

In addition, significantly more textual documentation has survived from Athens than other cities, allowing us to gain a better understanding of the artistic process and the creation of monuments such as the Acropolis.

Athens, beginning in the late sixth century B.C.E., was a democracy, in contrast to other Greek poleis which were primarily oligarchies or tyrannies. As with many democratic systems, Athens required the justification of expenditures to its citizens, meaning that the costs of its state-sponsored artistic projects, including notably the Acropolis building program, were recorded and displayed in public locations.

Soon after the defeat of the Persians in 490 B.C.E., Athenians began to practice ostracism as a way to prevent any one person from gaining too much power. Each year, people would meet in the Agora to vote as to whether any one person was too powerful or too close to becoming a tyrant. If the majority said yes, then another meeting was held during which citizens would write onto an ostrakon (piece of a potsherd used for a writing surface) the name of an individual they feared was too powerful; the individual who had the majority of votes was exiled for 10 years.

These ostraka from 482 B.C.E. were recovered from a well near the Acropolis and have the name of Themistocles written on them. He was a famous Athenian general, but would eventually be exiled (Ancient Agora Museum in Athens; photo: Zde, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Every male citizen was eligible (and obligated) to take part in Athens’ democratic system, serving in the assembly, juries, the army, and other governmental service. Yet, male citizens were only one part of a much larger population. In addition to citizens, metics (free non-citizens) and enslaved people lived in the city. Women, both citizens and non-citizens, were not eligible to take part in the government. Current scholarly estimates hypothesize a group of 30,000 to 60,000 male citizens ruling over a population of between 150,000 and 400,000 people.

A view of the Athenian Agora from the Acropolis

The Athenian Agora served as the physical center of Athens’ democracy, with many of its buildings hosting institutions central to the daily functioning of the government. Many cities had agoras, which were public open spaces used for gatherings or markets. In Athens, the Agora was in the center of the city, next to the Acropolis. It housed law courts, buildings where the boule (the city council) met, magistrates’ offices, mints, archives, temples, stores, and statues. It was the heart of public, civic life in Athens.

Watch a video about the agora

/1 Completed

Delian League, Athenian Empire, and the Acropolis Building Program

The Acropolis of Athens (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

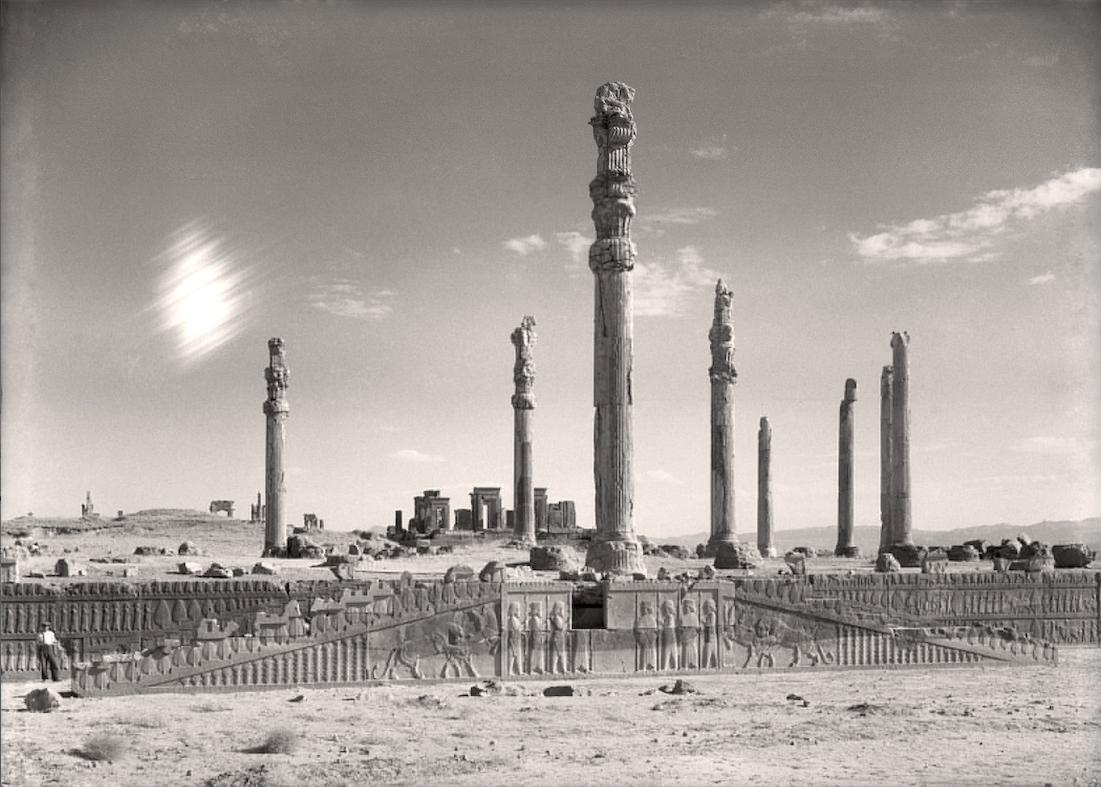

Athens acted as one of the military leaders in the Greco-Persian Wars, and emerged from the conflict as one of the most powerful poleis (city-states) in Greece. After the wars, they formed the Delian League, a federation of Greek cities located primarily on the coasts of the Aegean Sea in both mainland Greece and Asia Minor as well as on the Aegean islands, many of which had been under the control of Persia before the wars, and acted as its leader. Ostensibly, the Delian League was a federation of equals who joined together for defense, to prepare for another possible Persian invasion. Each city contributed ships and/or money, and the treasury was housed on the island of Delos. In reality, the league became an Athenian empire, as demonstrated most clearly by the movement of the treasury from Delos to Athens, where the Athenian democracy decided to use the money not for defense, but for the construction of the Acropolis Building Program.

Aerial view of the Acropolis (© Google)

The Acropolis, a flat topped hill in the center of the city, served as the heart of Athens’ religious life. The highly decorated, marble buildings functioned not only as a place to worship Athens’ most important deity, Athena, in monumental and lavish form, but to glorify the city of Athens and its people. They also served as victory monuments, commemorating the defeat of the Persians.

Remains of materials from the temples destroyed during the Persian sack of the Acropolis, such as column-drums (here) and a triglyph-metope frieze, were incorporated into the Acropolis North Wall.

In 480 and again in 479, the Persians sacked the city of Athens. While the city was mostly evacuated before the Persians entered, large portions of the city were destroyed, including the sacred structures on the Acropolis. The buildings that were constructed as part of the Acropolis Building Program (including the Temple of Athena Nike, the Parthenon, and the Erechtheion) were their replacements, and there were references to the Persian destruction and subsequent defeat across the Acropolis.

Temple of Athena Nike, 421–405 B.C.E., marble, Acropolis, Athens

Remnants of an archaic temple were left visible as a monument to the destruction, while the Temple of Athena Nike was decorated with friezes that depicted battles of Greeks and Persians, and the metopes of the Parthenon showed mythological battles that served as an allegory of the Persian defeat, presented as the triumph of civilization over barbarism.

Watch videos and read essays about the Acropolis building program

Temple of Athena Nike: It probably had a connection to the victory of the Greeks against the Persians around half a century earlier.

Read Now >

/4 Completed

Polykleitos, Doryphoros (Spear-Bearer) or Canon , Roman marble copy of a Greek bronze, c. 450–440 BCE (Museo Archaeologico Nazionale, Naples; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Outside of Athens, numerous statues and buildings also embraced the idealizing forms seen on the Acropolis. One statue that became one of the best known in the ancient world and representative of fifth-century artistic style was the Doryphoros by Polykleitos. The original bronze statue has not survived, but it was copied frequently in marble by the Romans, and discussed by a number of ancient writers.

It was also known as the canon, as Polykleitos attempted, in the statue, to achieve the perfect set of proportions for the male, human form. This was, for the artist, the pursuit of the ultimate beauty, which could be mathematically determined through symmetry and ideal proportions.

The goal of much of fifth-century art, like the Doryphoros and the buildings and sculptures on the Athenian Acropolis, was to pursue idealism with a detached appreciation of beauty on a philosophical level.

While the location of the original Doryphoros is debated, it was likely erected in a public place, perhaps in Polykleitos’ hometown of Argos. Greek statues were commissioned for various purposes, including as votive dedications in sanctuaries, grave markers, or monuments commemorating military victories or other civic or religious accomplishments. They were commissioned by both governments and individuals and displayed in both private and public contexts. Statues were made of various media, including terracotta, marble, and bronze.

Antikythera Youth, 340–330 B.C.E., bronze, 1.96 m high (National Archaeological Museum, Athens, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Many small-scale statues displayed in homes were made of terracotta, while metal or stone were used for more public dedications. Few bronze statues have survived, as the material could be melted down and used for other purposes in later periods, including notably for weapons or tools. Those bronze statues that have survived have done so primarily because they were lost in antiquity due to shipwreck, like the Antikythera Youth, or in other natural disasters, before their recovery in the modern period. Many of the bronze statues that were famous in the ancient period, like the Doryphoros, are known today only in marble Roman copies or through descriptions.

Painted mockup of Paris (?), west pediment sculptures, Temple of Aphaia, Island of Aegina, c. 490–480 B.C.E.

Most stone statues were made of white marble taken from quarries on the Greek islands, notably Paros, or the mainland at Mount Pentelikon near Athens. All of these statues, as well as marble architectural sculptures, were originally painted in bright colors, both their skin and clothing, and painted designs were frequently included on the sculpted fabric.

Antikythera Youth (detail), 340–330 B.C.E., bronze, 1.96 m high (National Archaeological Museum, Athens, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Even the bronze statues were colorful, with different types of alloys or metal treatments used to distinguish between the color of hair, skin, eyes, and clothing. The plain white marble that is found in most museums today would have been viewed as half-finished by a Greek viewer.

Traces of paint are still visible on many sculptures, including these from the Parthenon. Phidias (?), Sculpture from the east pediment of the Parthenon, marble, c. 448–432 B.C.E. (British Museum, London)

Watch videos about two sculptures

Polykleitos, Doryphoros (Spear-Bearer): The original bronze statue has not survived, but it was copied frequently and discussed by a number of ancient writers.

Read Now >

/2 Completed

The Peloponnesian War, its aftermath and images of women

Athens continued work on the Acropolis buildings throughout the second half of the fifth century, even after they became embroiled in the Peloponnesian War (431 to 404 B.C.E.). The war, fought between Athens and its allies against Sparta and its allies, was long and brutal. Athens eventually lost the war, along with much of its economic and military power, but the costs were high on both sides. Construction on the Acropolis continued intermittently during the fighting. This served, in part, as a public works project, providing jobs for Athenians whose livelihoods had been disrupted by the war, but primarily as a statement of Athens’ self-perceived power and glory.

Grave stele of Hegeso, c. 410 B.C.E., marble and paint, from the Dipylon Cemetary, Athens, 5′ 2″ (National Archaeological Museum, Athens)

Following the end of the Peloponnesian Wars, little art and architecture was commissioned at the state level in Athens, yet private commissions of artworks erected in public spaces, such as grave markers, were regularly made. These grave markers commemorate individuals and/or families, and depict idealized depictions of their honorees. They frequently highlight what were seen as the accomplishments of their honorees—service to the state and army for men, and families and oversight of the domestic sphere for women as seen in the Grave Stele of Hegeso. In classical Athens, women were not only disenfranchised from political life, but also limited in their own bodily and economic autonomy. Athenian women had a male guardian, usually a father or a husband, that made decisions for them regarding issues such as money, property, and divorce, their entire lives. Overseeing a prosperous household, bearing children, and taking part in religion were the expected accomplishments for women. Artworks like the Grave Stele of Hegeso therefore provide a valuable lens through which to examine gender roles in classical Greece.

Capitoline Venus, 2nd century C.E., marble, 193 cm (Capitoline Museums, Rome) (Roman copy of the Aphrodite of Knidos, a 4th century B.C.E. Greek original by Praxiteles)

While the male nude had long been a subject of Greek art, the first monumental statue of a female nude did not appear until the fourth century, when Praxiteles sculpted The Aphrodite of Knidos. Like the Doryphoros, the original artwork has not survived, but it is known through multiple copies and emulations, like the Capitoline Venus, as well as written descriptions.

Before this, partial and total female nudity was reserved for sex workers and victims of sexual assault in Greek art. Goddesses and heroines were not depicted nude, and female nudity did not have the same identifying characteristics of the heroic Greek as male nudity did. The Aphrodite of Knidos made the female nude an acceptable subject, and influenced generations of her descendants. Yet, female nudity was still limited, reserved only for certain figures. For instance, while Aphrodite, the goddess of erotic love, was regularly depicted nude, Athena, the goddess of strategic warfare, was not.

In addition, how Aphrodite was depicted differed from her male counterparts. Aphrodite of Knidos is shown bathing with a water jug and a large piece of drapery. She holds her hand across her body in front of her pubic triangle and turns her head to the side. This gesture has been interpreted by some scholars as drawing attention to her power as a goddess of sexuality, while others have viewed it as a gesture of vulnerability, as the goddess attempts to hide herself from unwanted male eyes. She is intended to be a portrait of female beauty, but whether that beauty is powerful or vulnerable still remains a question.

Watch videos about images of women made after the Peloponnesian War

Capitoline Venus (copy of the Aphrodite of Knidos): What did her nudity possibly mean to the Greeks?

Read Now >/2 Completed

In modern society, the term classical has become associated with a universally appealing artistic style of idealized depictions of perfect beauty, but the art of classical Greek art is better understood as a product of a specific period in Greek history. The fifth and fourth centuries saw multiple wars, as well as social and cultural upheaval. The Greeks were part of a larger Mediterranean and West Asian world that was connected by trade, diplomatic, and military ties, and these connections influenced their art. In the Classical period, this is seen most notably in their interactions with the Persians and the subsequent affect on their art and architecture. All this is reflected in classical idealism.

Key questions to guide your reading

What were the Greco-Persian Wars? Who fought in these wars and why? What was the impact of these wars on Greek art, politics, and society?

What buildings were constructed on the Athenian Acropolis in the fifth century B.C.E.? How do these buildings reflect the concerns of the Athenian democracy and its people?

How can Greek ideas of gender be seen in art produced in the fifth and fourth centuries B.C.E.? Was male and female nudity treated differently in Greek art?

Jump down to Terms to KnowWhat were the Greco-Persian Wars? Who fought in these wars and why? What was the impact of these wars on Greek art, politics, and society?

What buildings were constructed on the Athenian Acropolis in the fifth century B.C.E.? How do these buildings reflect the concerns of the Athenian democracy and its people?

How can Greek ideas of gender be seen in art produced in the fifth and fourth centuries B.C.E.? Was male and female nudity treated differently in Greek art?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

Agora

Classical

Contrapposto

Democracy

Greco-Persian Wars

Frieze

Idealism

Low relief

Metope

Pediment

Pelopponnesian War

Poleis (singular polis)

Severe Style