Learn about the great temple of Athena, patron of Athens, and the building’s long history.

Iktinos and Kallikrates (sculptural program directed by Phidias), Parthenon, 447–432 B.C.E. (Athens). Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

The many lives of the Parthenon

The Acropolis of Athens viewed from the Hill of the Muses (photo: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The Parthenon, as it appears today on the summit of the Acropolis, seems like a timeless monument—one that has been seamlessly transmitted from its moment of creation, some two and a half millennia ago, to the present. But this is not the case. In reality, the Parthenon has had instead a rich and complex series of lives that have significantly affected both what is left, and how we understand what remains.

Iktinos and Kallikrates, Parthenon, Acropolis, Athens, 447–432 B.C.E. (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

It is illuminating to examine the Parthenon’s ancient lives: its genesis in the aftermath of the Persian sack of the Acropolis in 490 B.C.E.; its accretions in the Hellenistic and Roman eras; and its transformation as the Roman empire became Christian. Why was the building created, and how was it understood by its first viewers? How did its meanings change over time? And why did it remain so important, even in Late Antiquity, that it was converted from a polytheist temple into a Christian church?

Investigating the many lives of the Parthenon has much to tell us about how we perceive (and misperceive) this famous ancient monument. It is also relevant to broader debates about monuments and cultural heritage. In recent years, there have been repeated calls to tear down or remove contested monuments, for instance, statues of Confederate generals in the southern United States. While these calls have been condemned by some as ahistorical, the experience of the Parthenon offers a different perspective. What it suggests is that monuments, while seemingly permanent, are in fact regularly altered; their natural condition is one of adaptation, transformation, and even destruction.

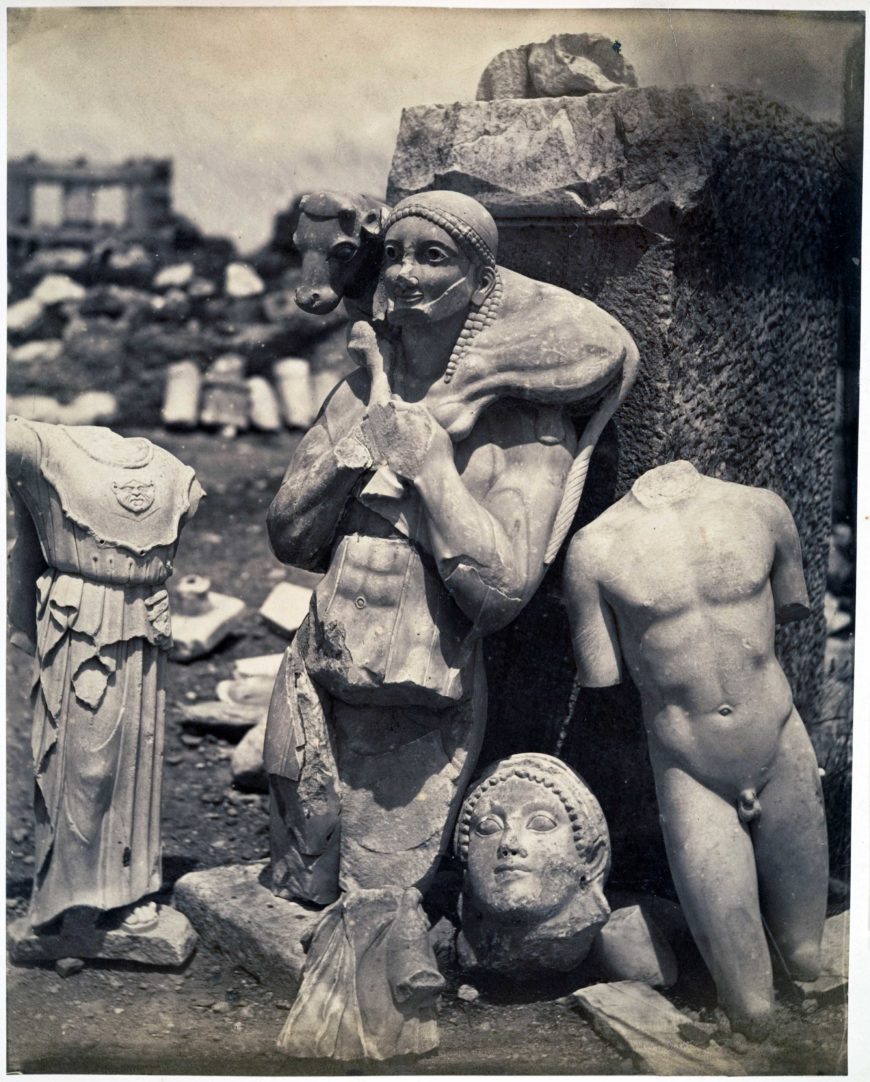

When Persians sacked Athens, they destroyed or damaged many sculptures, including the now-famous Calf-Bearer (today in the Acropolis Museum). Athenians buried many of these sculptures in a pit, which were not uncovered until the 19th century. Unknown photographer, The Calf-Bearer and the Kritios Boy Shortly After Exhumation on the Acropolis, 1865, albumen silver print from glass negative, 27.7 x 21.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

The Moschophoros or Calf-bearer, c. 570 B.C.E., marble 165 m high (Museum of the Acropolis of Athens; photo: Marysas, CC BY-SA 2.5)

The genesis of the Parthenon, 480–432 B.C.E.

The Parthenon we see today was not created ex novo. Instead, it was the final monument in a series, with perhaps as many as three Archaic predecessors. The penultimate work in this series was a marble building, almost identical in scale and on the same site as the later Parthenon, initiated in the aftermath of the First Persian War.

In the war in 492–490 B.C.E., Athens played a central role in the defeat of the Persians. Thus it is not surprising that ten years later when the Persians returned to Greece, they made for Athens; nor that, when they took the city, they sacked it with particular fervor. In the sack, they paid special attention to the Acropolis, Athens’s citadel. The Persians not only looted the rich sanctuaries at the summit, but also burned buildings, overturned statues, and smashed pots.

When the Athenians returned to the ruins of their city, they faced the question of what to do with their desecrated sanctuaries. They had to consider not only how to commemorate the destruction they had suffered, but also how to celebrate, through the rebuilding, their eventual victory in the Persian Wars.

Remains of materials from the temples destroyed during the Persian sack of the Acropolis, such as column-drums (shown here) and a triglyph-metope frieze, were incorporated into the North Wall (photo: Gary Todd)

The Athenians found no immediate solution to their challenge. Instead, for the next thirty years they experimented with a range of strategies to come to terms with their history. They left the temples themselves in ruins, despite the fact that the Acropolis continued to be a working sanctuary. They did, however, rebuild the walls of the citadel, incorporating within them some fire-damaged materials from the destroyed temples. They also created a new, more level surface on the Acropolis through terracing; in this fill, they buried all the sculptures damaged in the Persian sack. These actions, most likely initiated in the immediate aftermath of the destruction, were the only major interventions on the Acropolis for over thirty years.

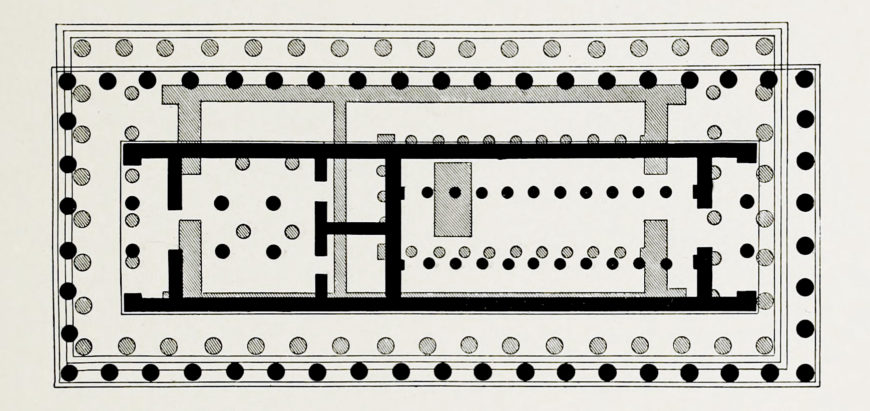

Plan of the Older Parthenon (in black) superimposed on that of the Parthenon (in gray). Plan by Maxime Collignon

In the mid-fifth century B.C.E., the Athenians decided, finally, to rebuild. On the site of the great marble temple burned by the Persians, they constructed a new one: the Parthenon we know today. They set it on the footprint of the earlier building, with only a few alterations; they also re-used in its construction every block from the Older Parthenon that had not been damaged by fire. In their recycling of materials, the Athenians saved time and expense, perhaps as much as one-quarter of the cost of construction.

The Older Parthenon foundation is located below the newer construction (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

At the same time, their re-use had advantages beyond the purely pragmatic. As they rebuilt on the footprint of the damaged temple and re-used its blocks, the Athenians could imagine that the Older Parthenon was reborn—larger and more impressive, but still intimately connected to the earlier sanctuary.

Battle of the Lapiths and Centaurs, Parthenon Metopes, south flank, marble, c. 440 B.C.E., Classical Period (British Museum, London; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

While the architecture of the Parthenon referenced the past through re-use, the sculptures on the building did so more allusively, re-telling the history of the Persian Wars through myth. This re-telling is clearest on the metopes that decorated the exterior of the temple. These metopes had myths, for instance, the contest between men and centaurs, that recast the Persian Wars as a battle between good and evil, civilization and barbarism.

The metopes did not, however, depict this battle as one of effortless victory. Instead, they showed the forces of civilization challenged and sometimes overcome: men wounded, struggling, even crushed by the barbaric centaurs. In this way, the Parthenon sculptures allowed the Athenians to acknowledge both their initial defeat and their eventual victory in the Persian Wars, distancing and selectively transforming history through myth.

Thus even in what might commonly be understood as the moment of genesis for the Parthenon, we can see the beginning of its many lives, its shifting significance over time. Left in ruins from 480 to 447 B.C.E., it was a monument directly implicated in the devastating sack of the Acropolis at the onset of the Second Persian War. As the Parthenon was rebuilt over the course of the following fifteen years, it became one that celebrated the successful conclusion to that war, even while acknowledging its suffering. This transformation in meaning presaged others to come, more nuanced and then more radical.

Hellenistic and Roman adaptations

By the Hellenistic era if not before, the Parthenon had taken on a canonical status, appearing as an authoritative monument in a manner familiar to us today. It was not, however, untouchable. Instead, precisely because of its authoritative status, it was adapted, particularly by those who sought to present themselves as the inheritors of Athens’ mantle.

The Parthenon was altered by a series of aspiring monarchs, both Hellenistic and Roman. Their goal was to pull the monument, anchored in the canonical past, toward the contemporary. They did so above all by equating later victories with Athens’ now-legendary struggles against the Persians.

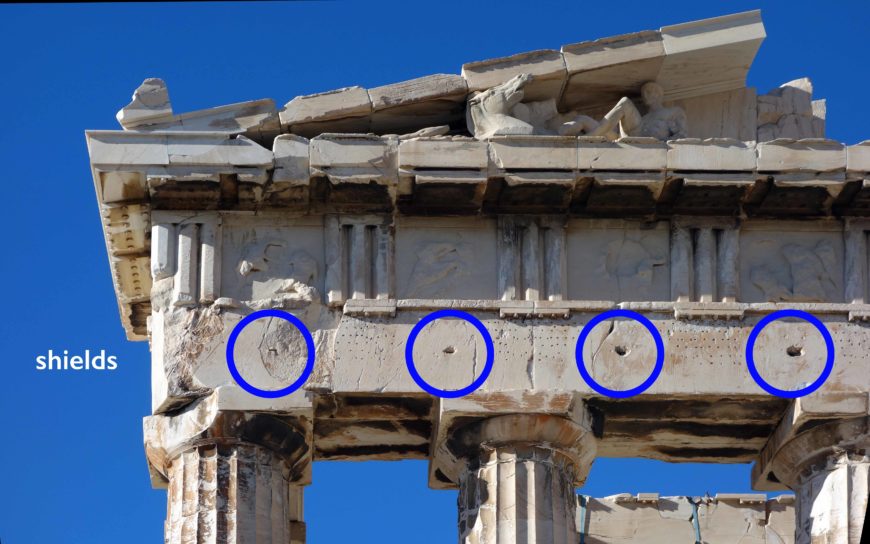

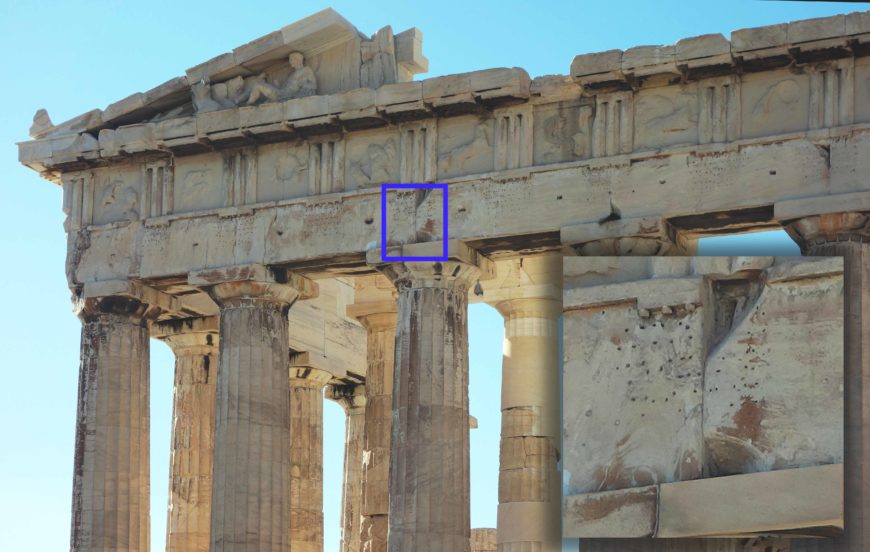

We can still see traces of the Persian shields from Alexander the Great that were at one point below the metopes. The blue circles indicate roughly were they would have been located (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The first of these aspiring monarchs was the Macedonian king Alexander the Great. As he sought to conquer the Achaemenid Empire—alleging, as one casus belli, the Persian destruction of Greek sanctuaries one hundred and fifty years earlier—Alexander made good propagandistic use of the Parthenon. After his first major victory over the Persians in 334 B.C.E., the Macedonian king sent to Athens three hundred suits of armor and weapons taken from his enemies. Likely with Alexander’s encouragement, the Athenians used them to adorn the Parthenon. There are still faint traces of the shields, once prominently placed just below the metopes on the temple’s exterior. Melted down long ago due to their valuable metal content, the shields must have been a highly visible memento of Alexander’s victory—and also of Athens’ subordination to his rule.

Wounded Gaul, from the Small Pergamene Votive Offering, Roman copy of the 2nd century C.E. from a Greek original of the 2nd century B.C.E. (Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples)

Some two centuries later, another Hellenistic monarch set up a larger and more artistically ambitious dedication on the Acropolis. Erected just to the south of the Parthenon, the monument celebrated the Pergamene kings’ victory over the Gauls in 241 B.C.E. It also suggested that this recent success was equivalent to earlier mythological and historical victories, with monumental sculptures that juxtaposed Gallic battles with those of gods and giants, men and Amazons, and Greeks and Persians. Like the shield dedication of Alexander, the Pergamene monument made good use of its placement on the Acropolis. The dedication highlighted connections between the powerful new monarchs of the Hellenistic era and the revered city-state of Athens, paying homage to Athens’ history while appropriating it for new purposes.

Holes for bronze letters of an inscription honoring the Roman emperor Nero on the east façade of the Parthenon, created and then removed in the 60s C.E. (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

A final royal intervention to the Parthenon came in the time of the Roman emperor Nero. This was an inscription on the east facade of the Parthenon, created with large bronze letters in between Alexander’s previously dedicated shields. The inscription recorded Athen’s vote in honor of the Roman ruler, and was likely put up in the early 60s C.E.; it was subsequently taken down following Nero’s assassination in 68. The inscription honored Nero by connecting him to Athens and to Alexander the Great, a model for the young philhellenic emperor. Its removal offered a different message. It was a deliberate and very public erasure of the controversial ruler from the historical record. In this, Nero’s inscription (and its removal) was perhaps the most striking rewriting of the Parthenon’s history—at least until Christian times.

Reviewing the Hellenistic and Roman adaptations of the Parthenon, it is easy to see them purely as desecrations: appropriations of a religious monument for political and propagandistic purposes. And the speedy removal of Nero’s inscription does support this reading, at least for the visually aggressive strategies of the Roman emperor. At the same time, the changes of the Hellenistic and Roman eras are also testimony to the continued vitality of the sanctuary. Due to the prestige of the Parthenon, formidable monarchs sought to stake their visual claims to power on what was by now a very old monument, over four centuries old by the time of Nero. By altering the temple and updating its meanings, they kept it young.

Marble closure slab with relief cross, from the pulpit of the Christian Parthenon, 5th–6th century (Byzantine and Christian Museum, Athens (photo: George E. Koronaios, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Early Christian transformations

In ancient times, the most radical and absolute transformation of the Parthenon came as the Roman empire became Christian. At that point, the temple of Athena Parthenos was turned into an Early Christian church dedicated to the Theotokos (Mother of God). As with the rebuilding of the Parthenon in the mid-fifth century B.C.E., the decision to put a Christian church on the site of Athena’s temple was not just pragmatic but programmatic.

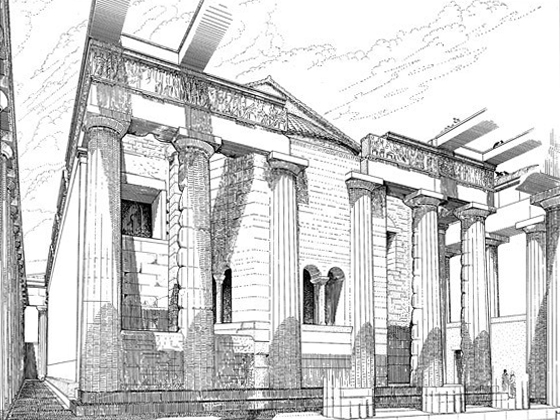

Reconstruction drawing of the church inside the Parthenon by M. Korres from Panayotis Tournikiotis, The Parthenon and Its Impact in Modern Times (New York, 1996)

By transforming the polytheist sanctuary into a space of Christian worship, it provided a clear example of the victory of Christianity over traditional religion. At the same time, it also effectively removed, through re-use, an important and long-enduring center of polytheist cult. This removal through re-use was a characteristic strategy used by the Christians throughout the Roman Empire, from Turkey to Egypt to the German frontier. In all these places, it formed part of the often violent, yet imperially sanctioned, transition from polytheism to Christianity.

The Christian transformation of the Parthenon involved considerable adaptation of its architecture. The Christians needed a large interior space for congregation, unlike the polytheists, whose most important ceremonies took place at a separate altar, outdoors. To repurpose the building, the Christians renovated the inner cella of the Parthenon. They detached it from its exterior colonnade, added an apse that broke through the columns at the east end, and removed from the interior the statue of Athena Parthenos that had been the raison d’étre of the polytheist temple.

Metope from the east side of the Parthenon showing the battle of men and Amazons, heavily cut down by early Christians (photo: Gary Todd)

Other sculptures from the Parthenon suffered likewise from the Christians’ attentions. Most of the metopes—the lowest down and most visible of the Parthenon’s sculptures—were cut away, rendering them difficult to interpret or to use as a focus of polytheist cult. Only the south metopes with the centaurs were spared, perhaps because they overlooked the edge of the Acropolis and were thus hard to see. By contrast, the frieze (hidden between the exterior and interior colonnades) was left almost entirely intact, as were the high-up pediments. The differentiated treatment of the various sculptures on the Parthenon suggests negotiation between traditionalists and the more fervent of the contemporary Christians. Polytheists perhaps sacrificed the relatively small-scale and blatantly mythological metopes to keep the larger, better quality sculptures elsewhere on the monument. Examining the frieze, about one hundred sixty meters long and almost perfectly preserved, it seems like the polytheists got a good deal.

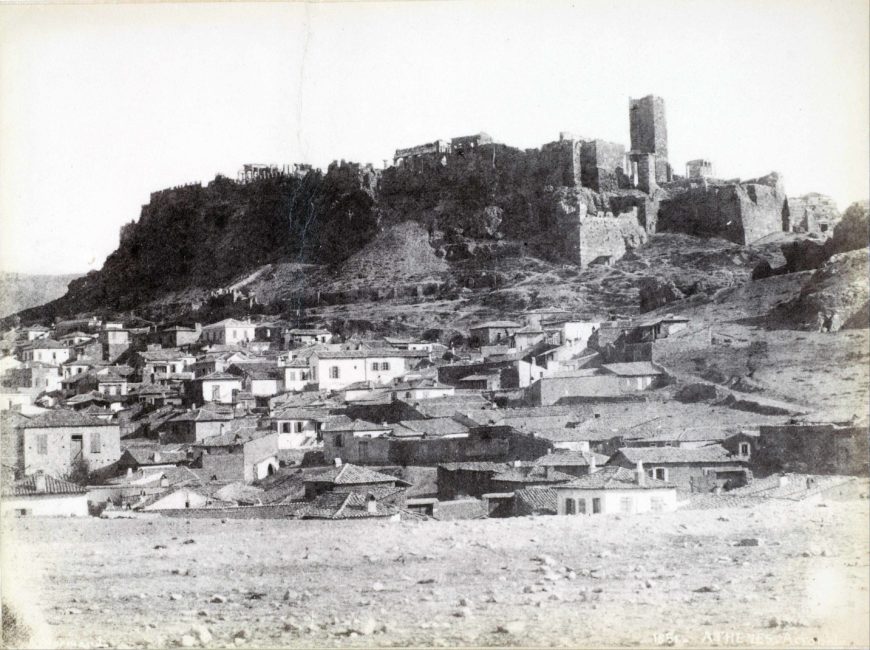

19th-century photographs show the Frankish tower and Ottoman dome (not visible here) that was once part of the Acropolis. Normand Alfred Nicolas, The northwest side of the Acropolis and the surrounding area, 1851, photograph (Benaki Museum, Athens)

Conclusions

Within and beyond the ancient world, the Parthenon had many lives. Rather than ignoring them, it is useful to acknowledge these lives as contributions to the building’s extraordinary continuing vitality. At the same time, one might note that the biography of the Parthenon (though accessible to specialists) has been decidedly effaced by the way it is presented now. When contrasting its present-day state with the first photographs taken in the mid-nineteenth century, we can see how much has been intentionally removed: a Frankish tower by the entrance to the Acropolis, an Ottoman dome, mundane habitations.

Iktinos and Kallikrates, Parthenon, Acropolis, Athens, 447–432 B.C.E. (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In its current iteration, the Acropolis has been returned to something resembling its pristine Classical condition, with no reconstructed monuments dating later than the end of the 5th century B.C.E. This feels like a loss: a retardataire effort to reinstate a selective, approved version of the past and to erase the traces of a more difficult and complex history. As such it stands as an example, and perhaps also a warning, for our current historical moment.

Additional resources

The Parthenon sculptures at The British Museum

History of the Acropolis from Greece’s Ministry of Culture and Sports

B.F. Cook, The Elgin Marbles (London: The British Museum Press, 1997).

Jeffrey Hurwit, The Athenian Acropolis: History, mythology, and archaeology from the Neolithic era to the present (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

Rachel Kousser, “Destruction and memory on the Athenian Acropolis,” Art Bulletin, volume 91, number 3 (2009), pp. 263–82.

R. R. Smith, “Defacing the gods at Aphrodisias,” Historical and Religious Memory in the Ancient World, edited by R. R. Smith and B. Dignas (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2012), pp. 282–326.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”parthenon,”]

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:05] We’re looking at the Parthenon. This is a huge marble temple to the goddess Athena.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:11] We’re on the top of a rocky outcropping in the city of Athens, very high up overlooking the city, overlooking the Aegean Sea.

Dr. Zucker: [0:21] Now, Athens was just one of many Greek city-states. Almost everyone had an acropolis, that is, had a fortified hill within its city, because these were warring states.

Dr. Harris: [0:30] In the 5th century, Athens was the most powerful city-state. That’s the period that the Parthenon dates to.

Dr. Zucker: [0:37] This precinct became a sacred one rather than a defensive one. This building has had tremendous influence. Not only because it becomes the symbol of the birth of democracy, but also because of its extraordinary architectural refinement.

[0:49] The period when this was built, in the 5th century, is considered the High Classical moment, and for so much of Western history, we have measured our later achievements against this perfection.

Dr. Harris: [1:00] It’s hard not to recognize so many buildings in the West. There’s certainly an association, especially, to buildings in Washington, D.C., and that’s not a coincidence.

Dr. Zucker: [1:09] Because this is the birthplace of democracy. It was a limited democracy but democracy nevertheless.

Dr. Harris: [1:14] There was a series of reforms in the 5th century in Athens that allowed more and more people to participate in the government.

Dr. Zucker: [1:22] We think that the city of Athens had between 300 and 400,000 inhabitants, and only about 50,000 were considered citizens. If you were a woman, obviously if you were a slave, you were not participating in this democratic experiment.

Dr. Harris: [1:37] This is a very limited idea of democracy.

Dr. Zucker: [1:40] This building is dedicated to Athena. In fact, the city itself is named after her. Of course, there’s a myth.

[1:46] Two gods vying for the honor of being the patron of this city.

Dr. Harris: [1:49] Those two gods are Poseidon and Athena. Poseidon is the god of the sea. Athena has many aspects. She’s the goddess of wisdom. She is associated with war, a kind of intelligence about creating and making things.

Dr. Zucker: [2:03] Both of these gods gave the people of the city a gift and then they had to choose. Poseidon strikes a rock, and from it springs forth the salt water of the sea. This had to do with the gift of naval superiority.

Dr. Harris: [2:15] Athena offered, in contrast, an olive tree, the idea of the land of prosperity, of peace.

[2:22] The Athenians chose Athena’s gift. There is a site here on the Acropolis where the Athenians believed you could see the mark of the trident from Poseidon, where he struck the ground, and also the tree that Athena offered.

Dr. Zucker: [2:37] Actually, the modern Greeks have replanted an olive tree in that space. Let’s talk about the building. It is really what we think of when we think of a Greek temple, but the style is specific. This is a Doric temple.

Dr. Harris: [2:47] Although it has Ionic elements, which we’ll get to.

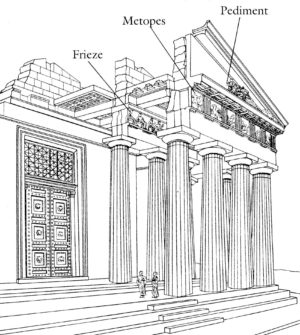

Dr. Zucker: [2:50] The Doric features are really easy to identify. You have massive columns with shallow, broad flutes — the vertical lines. Those columns go down directly into the floor of the temple, which is called the stylobate, and at the top, the capitals are very simple. There’s a little flare that rises up to a simple rectangular block called an abacus, and just above that are triglyphs and metopes.

Dr. Harris: [3:13] It’s important to say that this building was covered with sculpture. There was sculpture in the metopes. There was sculpture in the pediments, and in an unprecedented way, a frieze that ran all the way around all four sides of the building, just inside this outer row of columns that we see. Now, this is an Ionic feature. Art historians talk about how this building combines Doric elements with Ionic elements.

Dr. Zucker: [3:39] In fact, there were four Ionic columns inside the west end of the temple.

Dr. Harris: [3:44] When the citizens of Athens walked up the Sacred Way, perhaps for a religious procession or festival, they encountered the west end, and they walked around it either on the north or south sides to the east and the entrance.

[3:58] Right above the entrance, in the sculptures of the pediment, they could see the story of Athena and Poseidon vying to be the patron of the city of Athens.

[4:07] On the frieze just inside, they saw themselves, perhaps, at least in one interpretation, involved in the Panathenaic procession, the religious procession in honor of the goddess Athena. This was a building that you walked up to, you walked around, and inside was this gigantic sculpture of Athena.

Dr. Zucker: [4:28] These were all sculptures that we believe were overseen by the great sculptor Phidias. One of my favorite parts are the metopes carved with scenes that showed the Greeks battling various enemies, either directly or metaphorically.

[4:42] The Greeks battling the Amazons, the Greeks against the Trojans, the Lapiths against the centaurs, and the Gigantomachy, the Greek gods against the Titans.

Dr. Harris: [4:52] All of these battles signify the ascendancy of Greece and of the Athenians, of their triumphs, civilization over barbarism, of rational thought over chaos.

Dr. Zucker: [5:03] You’ve just hit on the very meaning of this building. This is not the first temple to Athena on this site. Just a little bit to the right as we look at the east end, there was an older temple to Athena that was destroyed when the Persians invaded. This was a devastating blow to the Athenians.

Dr. Harris: [5:20] One really can’t overstate the importance of the Persian War for the Athenian mindset that created the Parthenon. Athens was invaded, and beyond that, the Persians sacked the Acropolis. Sacked the sacred site, the temples, destroyed the buildings.

Dr. Zucker: [5:37] They burned them down. In fact, the Athenians took a vow that they would never remove the ruins of the old temple to Athena.

Dr. Harris: [5:44] So they would remember it forever.

Dr. Zucker: [5:46] But a generation later they did.

Dr. Harris: [5:48] They did. Well, there was a peace that was established with the Persians and some historians think that that allowed them to renege on that vow. And Pericles, the leader of Athens, embarked on this enormous, very expensive building campaign.

Dr. Zucker: [6:02] Historians believe that he was able to fund that because the Athenians had become the leaders of what is called the Delian League, an association of Greek city-states that paid a kind of tax to help protect Greece against Persia, but Pericles dipped into that treasury and built this building.

Dr. Harris: [6:19] This alliance of Greek city-states, their treasure, their tax money, their tribute, was originally located in Delos, hence the name Delian League, but Pericles managed to have that treasure moved here to Athens and actually housed in the Acropolis.

[6:35] The sculpture of Athena herself, which was made of gold and ivory — Phidias said, “If we need money, we can melt down the enormous amount of gold that decorates the sculpture of Athena.”

Dr. Zucker: [6:46] Since that sculpture doesn’t exist any longer, we know somebody did that.

Dr. Harris: [6:50] [laughs]

Dr. Zucker: [6:50] So we need to imagine this building not pristine and white, but rather brightly colored and also a building that was used. This was a storehouse, it was the treasury, and so we have to imagine that it was absolutely full of valuable stuff.

Dr. Harris: [7:04] In fact, we have records that give us some idea of what was stored here. We think about temples or churches or mosques as places where you go in to worship, but that’s not how Greek religion worked.

[7:16] There usually was an altar on the outside where sacrifices were made and the temple was the house of the god or goddess, but with the Parthenon, art historians and archaeologists have not been able to locate an altar outside, so we’ve wondered, “What was this building?” One answer is it was a treasury.

Dr. Zucker: [7:34] But it also functions symbolically. It is up on this hill. It commands this extraordinary view from all parts of the city, so it was a symbol of both the city’s wealth and power.

Dr. Harris: [7:44] It’s a gift to Athena. When you make a gift to your patron goddess, you want visitors to be awed by the image of the goddess that was inside and of her home.

Dr. Zucker: [7:54] This isn’t any goddess, this is the goddess of wisdom. The ability of man to understand our world and its rules mathematically and then to express them in a structure like this is absolutely appropriate.

Dr. Harris: [8:06] Iktinos was a supreme mathematician. We know that the Greeks, even in the Archaic period before this, were concerned with ideal proportions.

Dr. Zucker: [8:16] Pythagoras.

Dr. Harris: [8:17] Or the sculptor Polykleitos and his sculpture of the Doryphoros, searching for perfect proportions and harmony and using mathematics as the basis for thinking that through.

Dr. Zucker: [8:28] We have that here.

Dr. Harris: [8:30] To an unbelievable degree.

Dr. Zucker: [8:33] What’s extraordinary is that its perfection is an illusion based on a series of subtle distortions that actually correct for the imperfections of our sight.

[8:44] That is, the Greeks recognized that human perception was itself flawed, and that they needed to adjust for it in order to give the visual impression of perfection, and their mathematics and their building skills were precise enough to be able to pull this off.

Dr. Harris: [9:00] Every stone was cut to fit precisely.

Dr. Zucker: [9:03] Well, when we look at this building, we assume it’s rectilinear, it’s full of right angles, and in fact, there’s hardly a right angle in this building.

Dr. Harris: [9:10] There’s another interpretation of these tiny deviations, that these deviations give the building a sense of dynamism, the sense of the organic [in what] otherwise would seem static and lifeless. The Greeks had used this idea that art historians call “entasis” before in other buildings. Slight adjustments.

[9:28] For example, columns bulged toward the center. This is not new, but the degree to which it’s used here and the subtlety in the way it’s used is unprecedented.

Dr. Zucker: [9:38] For instance, in those Doric columns, you can see that there’s a taper and you assume that it’s a straight line, but the Greeks wanted ever so slight a sense of the organic. That the weight of the building was being expressed in the bulge, the entasis of the column, about a third of the way from the bottom.

[9:55] In this case, every single column bulges only 11/16 of an inch the entire length of that column. The way that the Greeks pulled this off is they would bring column drums up to the site, they would carefully carve the base and the top, and then they would carve in between.

Dr. Harris: [10:12] We see this slight deviation in the columns, but we also see it not only vertically but also horizontally in the building.

Dr. Zucker: [10:21] Well, that’s right. You assume that the stylobate, the floor of the temple, is flat, but it’s not. Rainwater would run off it because the edges are lower than the center.

Dr. Harris: [10:29] But only very, [laughs] very slightly lower.

Dr. Zucker: [10:32] Across the long sides of the temple the center rises only 4 and 3/8 of an inch, and on the short sides of the temple on the east and the west side, the center rises only by 2 3/8 inches. What happens is it cracks. Our eye would naturally see a straight line seem as if it rises up at the corners a little bit so it seems to us to be perfectly flat. The columns are all leaning in a little bit.

Dr. Harris: [10:58] You would expect the columns to be equidistant from one another, but in fact the columns on the edges are slightly closer to one another than the columns in the center of each side.

Dr. Zucker: [11:08] Architectural historians have hypothesized that the reason for this is because the column at the edge is in a sense an orphan. It doesn’t have anything past it. Therefore, it would seem to be less substantial.

[11:22] If we could make that column a little bit closer to the one next to it it might compensate, and it would have an even sense of density across the building.

Dr. Harris: [11:29] Placing of the columns closer together on the edges created a problem in the levels above. One of the rules of the Doric order is that there had to be a triglyph right above the center of a column or in between each column.

Dr. Zucker: [11:42] They also wanted the triglyphs to be at the very edge so one triglyph would abut against another triglyph at the corner of the building. If in fact you’re placing your columns closer together, you can actually solve for that problem.

[11:56] You can avoid the stretch of the metope in between those triglyphs that would result, but because the columns are placed so close together they had the opposite problem, which is to say that the metopes at the ends of the building would be too slender.

[12:11] What Phidias has done in concert with Iktinos and Kallikrates, the architects, is to create sculptural metopes that are widest in the center, just like the spaces between the columns, and actually, the metopes themselves gradually become thinner as you move to the edges so that you can’t really even perceive the change without measuring.

Dr. Harris: [12:29] And the general proportions of the building can be expressed mathematically as X = Y x 2 + 1. Across the front, we see 8 columns, and along the sides, 17 columns. That ratio also governs the spacing between the columns and its relationship to the diameter of a column. Math is everywhere.

Dr. Zucker: [12:53] If we look at the plan of the structure, we see the exterior colonnade on all four sides. On the east and west end, it’s actually a double colonnade, and on the long sides, inside the columns, a solid masonry wall. You can enter rooms on the east and west only.

[13:09] The west has a smaller room with the four Ionic columns within it, but the east room was larger and held the monumental sculpture of Athena.

[13:09] It’s interesting, the system that was used to create a vaut that was high enough to enclose a sculpture that was almost 40 feet high was unique. There was a U shape of interior columns at two storeys. They were Doric and they surrounded the goddess.

[13:30] The sculpture is now lost, but the building was almost lost as well. Here we come to one of the great tragedies of Western architecture. This building survived into the 17th century and was in pretty good shape for 2,000 years, and it’s only in the modern era that it became a ruin.

Dr. Harris: [13:46] First it was, as we know, an ancient Greek temple for Athena, then it became a Greek Orthodox Church, then a Roman Catholic Church, and then a mosque.

[13:56] In a war between the Ottomans, who were in control of Greece at this moment in history in the 17th century, and the Venetians, the Venetians attacked the Parthenon. The Ottomans used the Parthenon to hold ammunition and gunpowder. Gunpowder exploded from the inside, basically ripping the guts out of the Parthenon.

Dr. Zucker: [14:15] Then, to add insult to injury, in the 18th century Lord Elgin received permission from the Turkish government to take sculptures that had already fallen off the temple and bring them back to England. The lion’s share of the great sculptures by Phidias are now in London.

[14:31] Greece recently has built a museum just down the hill from the Acropolis specifically intended to house these sculptures should the British ever release them.

Dr. Harris: [14:40] Some have argued that Elgin saved the sculptures that would have been further damaged had he not removed them, but what to do about the future is uncertain.

Dr. Zucker: [14:49] At least one theory states that this building was paid for by plundered treasury from the Delian League so there’s a long history of contested ownership.

Dr. Harris: [14:57] As we stand here very high up on the Acropolis overlooking the Aegean Sea, islands beyond, and mountains on this glorious day, I can’t help but imagine standing inside the Parthenon between those columns, which we can’t do today.

Dr. Zucker: [15:14] The site is undergoing tremendous restoration. There are cranes, the scaffolding to maintain the ruin and not let it fall into worse disrepair.

Dr. Harris: [15:23] If we could stand there, what would it feel like?

Dr. Zucker: [15:26] There is this beautiful balance between the theoretical and the physical. The Greeks thought about mathematics as the way that we could understand the divine, and here it is in our world.

Dr. Harris: [15:36] There’s something about the Parthenon that is both an offering to Athena, the protector of Athens, but also something that’s a monument to human beings, to the Athenians, to their brilliance, and by extension, I suppose in the modern era, human spirit generally.

[15:52] [music]