New wars, social change, and the American Dream

Essay by Dr. Kelly Enright

Seven miles of traffic backed up the Santa Ana Freeway on a hot July day in 1955. Families in their vehicles baked in the sun while waiting to arrive at the opening of filmmaker Walt Disney’s new California amusement park. The much-anticipated opening of Disneyland brought a crowd connected by popular culture and eager for respectable middle-class entertainment.

The Disneyland parking lot on opening day, 1955 (University of Southern California, Los Angeles Examiner Photographs Collection, 1920-1961)

The freeway that connected them to the park had only recently been built. Freeways and interstate highways throughout the nation connected people to burgeoning suburbs and the promise of the American dream, a peaceful family life, and home ownership.

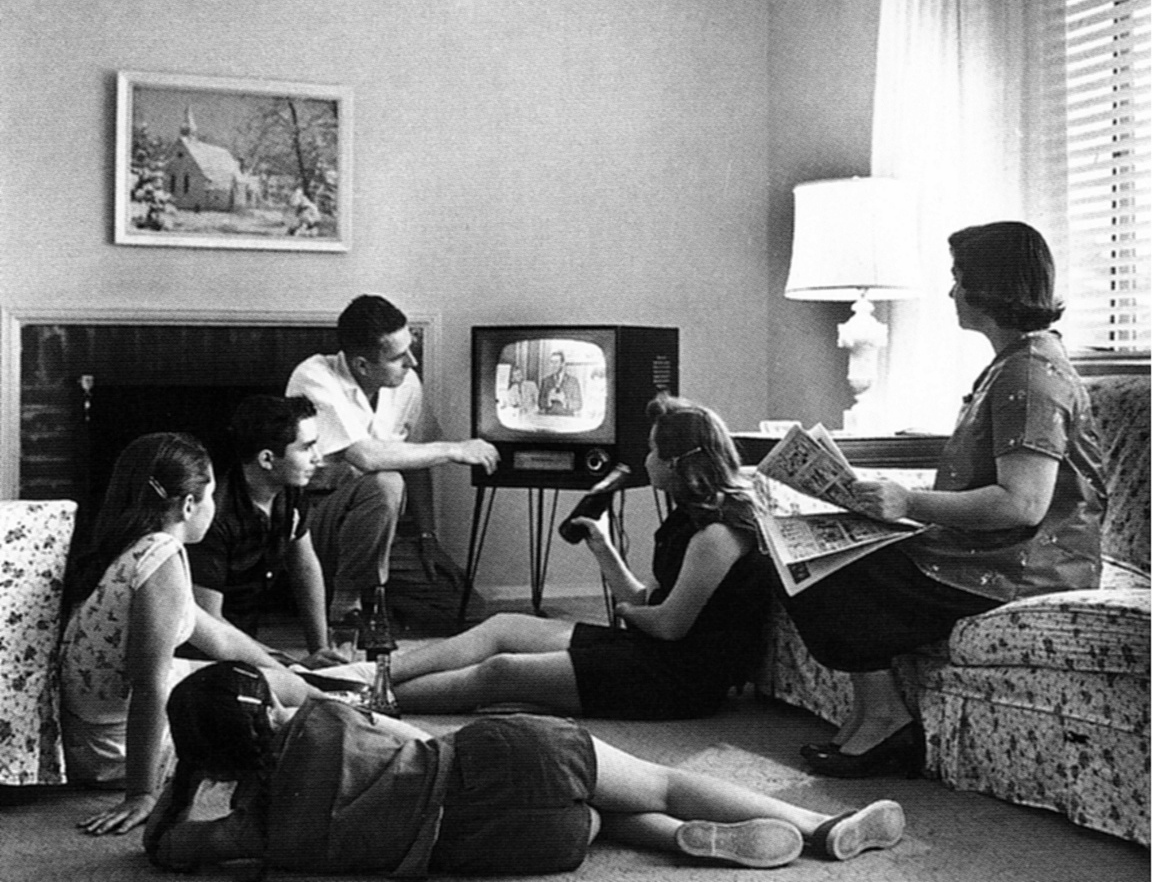

Inside those homes, families watched television programs that packaged the American middle class lifestyle in cheery and gender-stratified roles. This seemingly simple conformist society quickly gave way to conflicts in the 1960s and 70s that unmasked discontents that lurked behind post-war prosperity.

In the summer of 1955, the opening of Disneyland signaled the fictions of the screen come to life. The entire park landscape questioned the division between fantasy and reality, and blurred the lines between history and fairytale.

Disney’s Main Street USA represented nostalgia for an imagined naïve America before the war, while Tomorrowland optimistically cast technology as the road to national contentment. Lost in this land, Americans suspended their disbelief, entertained their children and themselves, and, as the century progressed, escaped their increasingly complex social and political present.

Tomorrowland actors at Disneyland (Disney Parks)

A new war

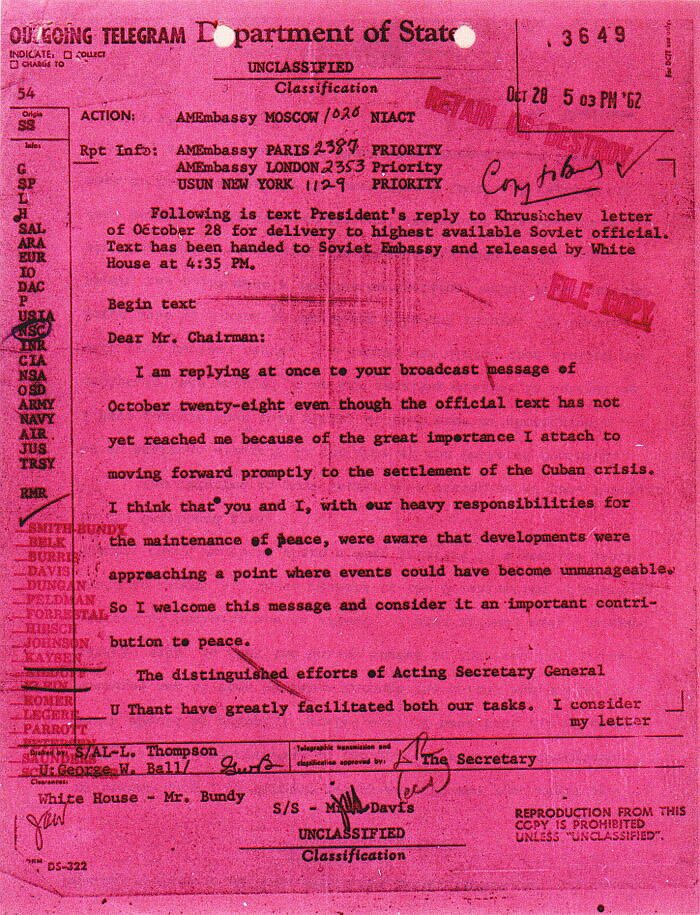

Emerging from the conflict of World War II as a dominant power, the U.S. embroiled itself in a new conflict — the Cold War. With the Marshall Plan, the U.S. helped aid recovery in Western Europe and Asia, but the underlying goal, to stop Communist expansion, led to an arms race with the Soviet Union and culminated, in 1962, in an event that brought the world to the brink of nuclear war — the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Telegram from President Kennedy to Soviet officials on October 28th, 1962 (John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum)

In attempts to stop Russia and China’s communist models from being replicated, the U.S. engaged in wars in both Korea and Vietnam. Fear of communists at home reemerged as well. Unions were investigated for pro-communist leaders beginning in 1947 and, in 1950, Senator Joe McCarthy investigated suspected spies inside the U.S. government using methods widely seen as an abuse of power.

Throughout the 1960s, the space race promoted technology as political prowess. The Soviets launched the first man-made satellite of earth, Sputnik, while the U.S. landed the first man on the moon in 1969. But, with the aftermath of the atomic bomb that had ended the world war, Americans in the mid-twentieth century also questioned technology’s impact upon society and the environment.

A family watches television, c. 1958 (National Archives and Records Administration, public domain)

Cultural changes

Entering the 1950s, elements of the New Deal remained strong with many in support of unions and business regulation. As a result, the post-war middle class grew — as did the population in an unsurpassed “baby boom” that lasted until the 1960s.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower funded an expansive interstate highway system just as affordable cookie-cutter houses popped up in growing suburban neighborhoods. American dreams of home-owning and the accoutrements of middle class life became more accessible to white Americans who increasing fled from cities. In addition, with the Fair Labor Standards Act and the establishment of a regulated 40-hour work week in most industries and paid leisure time, came the motels, and tourist attractions that began to dot the new highway system. Consumer culture depicting this new American lifestyle rapidly spread through television programs and advertisements.

Kodak advertisement showing a family on holiday, Look Magazine, July, 1949 (image: Classic Film, CC BY-NC 2.0)

With young people newly able to enjoy increasing leisure time, a teenage culture thrived. It rebelled against postwar conformity while simultaneously becoming mainstream and commercially potent. Rock and roll music grew in popularity during this era, with the controversial moves of Elvis Presley ringing in the phenomenon.

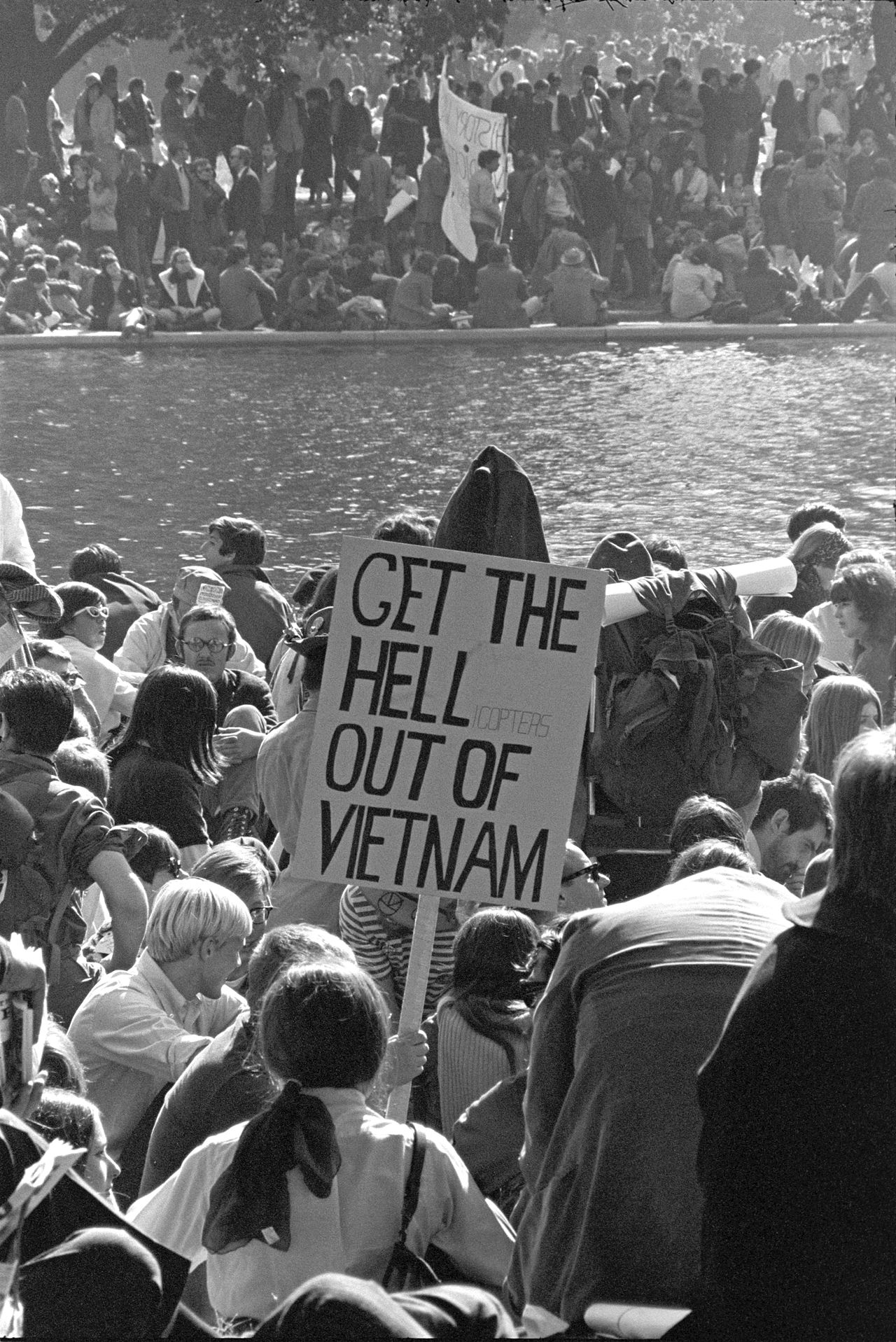

Anti-war protestors, 1967 (Lyndon B. Johnson Library and Museum)

Popular music began to express the feelings, as well as the politics, of the younger generation through performers like Bob Dylan and the Beatles. Hollywood portrayed appealing rebels and “greasers” while the Beat Generation sought isolation from the reach of popular culture and consumerism.

This generation grew to launch protests against unjust politics, racial and gender discrimination, and the Vietnam War. The countercultural movements of the 1960s and 70s also sought to change attitudes about sexuality, homosexuality, reproductive rights, and divorce.

Women who had worked in jobs on the home front while men were fighting World War II, had been pushed back into the domestic realm. In 1963, Betty Friedan expressed the discontent of housewives in the book The Feminine Mystique and helped found the National Organization for Women. She was among the promotors of the Equal Rights Amendment which ultimately failed to pass — leaving the legal protection of equal opportunities for women in the hands of other, narrower federal laws, and piecemeal state regulations.

Women’s Liberation march, Washington, D.C., 1970 (Library of Congress)

With the legalization of contraception and abortion, and the introduction of the Pill, women found they could more easily delay marriage and children to pursue careers. But as the work of the artist Mierle Ukeles makes clear, women continue to struggle in the modern workplace.

The Great Society

When John F. Kennedy was elected president in 1960, he was the youngest to ever serve in that office, and he was the first Catholic to do so. His promise was to build a Great Society that was both democratic and equal.

Before his assassination in 1963, JFK began pushing federal programs aimed at alleviating poverty and dismantling segregation, as well as introducing Medicare, federal financial aid for education, funding for arts, and environmental protections. Though these plans were ultimately implemented under Lyndon B. Johnson, JFK’s celebrity only grew after his death.

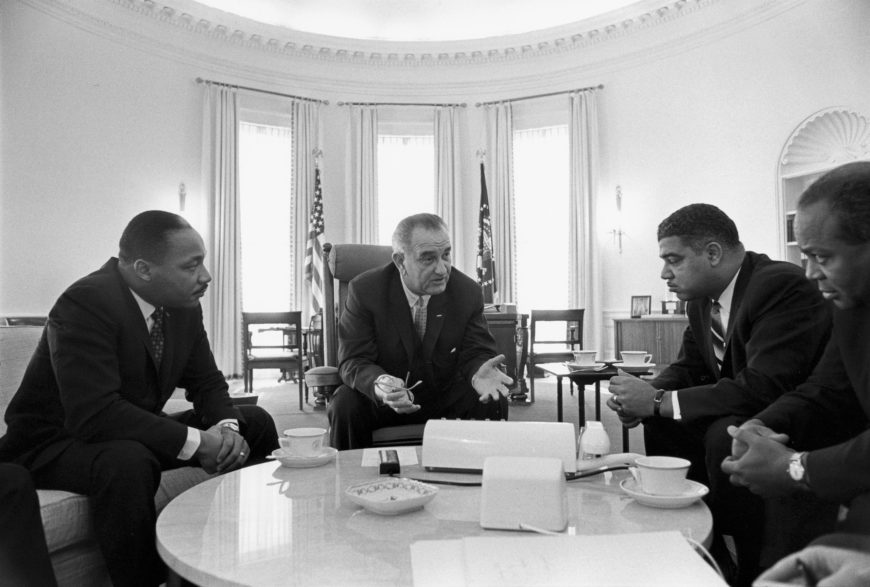

President Lyndon B. Johnson with Civil Rights leaders Martin Luther King, Jr., Whitney Young, and James Farmer, 1964 (Lyndon B. Johnson Library and Museum)

Among the legislation that President Johnson pushed forward were the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, marking major victories for the civil rights movement. The 1950s saw several landmark U.S. Supreme Court decisions that were important moves toward racial equality, but none fully established desegregation. Brown v. Board of Education (1954), for example, ended “separate but equal” but left implementation to the states where there were often long traditions of racial discrimination.

Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C. (Library of Congress)

Many civil rights leaders, such as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., promoted peaceful direct action, such as boycotts and sit-ins, to demonstrate African American resistance to segregation, while other civil rights leaders wished for a more radical course of action. Nonviolent tactics, sought to bring awareness through media coverage and political attention, to the plight of their cause, but even peaceful actions were met with violence and arrests by police.

While African Americans had long fought for equal rights through such actions, the protests of the civil rights movement grew to include women, Native Americans, LGBT, and other marginalized Americans. The momentum of these movements also helped to galvanize protests to the Vietnam War as people questioned the purpose and the expansion of American involvement in Southeast Asia.

Front page of The New York Times, 1 May, 1970

When Richard Nixon took office, he expanded the war beyond Vietnam to the neighboring country of Cambodia, further escalating protests against the war. Demonstrations at Kent State and Jackson State resulted in live fire from the National Guard and police, fueling nationwide protests not just against the war but against the government’s abandonment of the principles of law and order.

A new reality

In 1973, cars backed up along roadways not in anticipation of the fantasies of Disneyland but in long lines at gas stations as the oil crisis limited availability of the commodity that fueled twentieth-century America.

As the 1970s came to an end, the culture war between conservatives, liberals, and the New Left simmered. The liberal decades after the Second World War ended with a swing to conservatism signaled by the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980.

What had begun as a tranquil era of idealism ended with an awareness that inequality and other injustices had undermined the American dream. Throughout the 1970s, many had become uncertain or discontent with their role in society, unsure of future economic prosperity, and confused about the ethical course of the American political system.

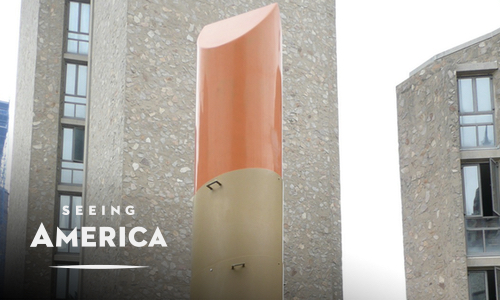

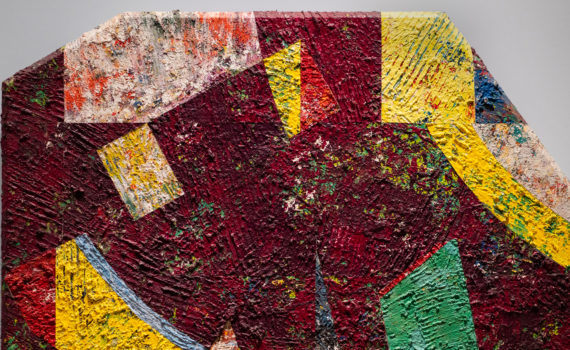

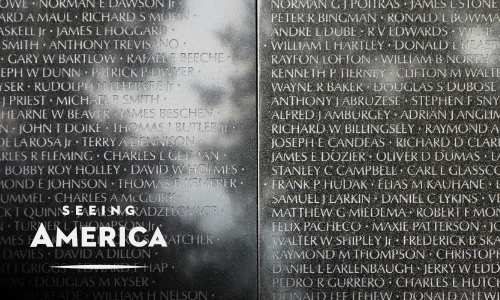

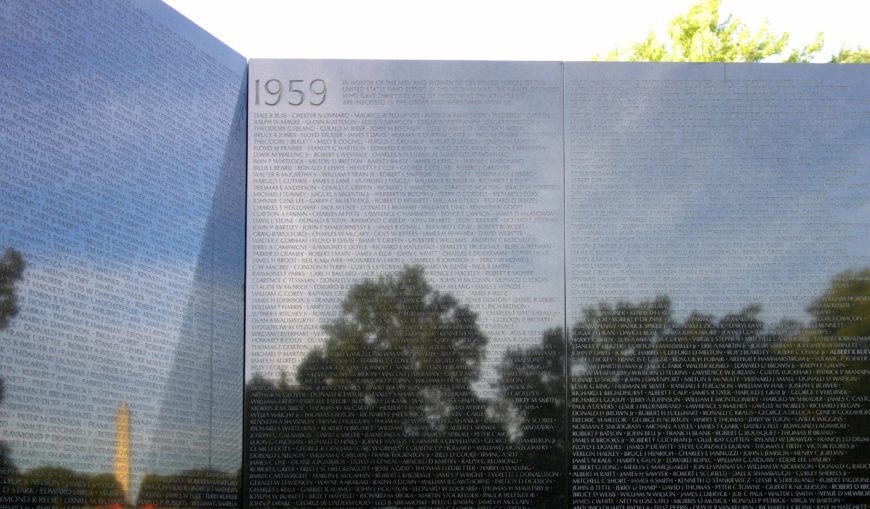

Maya Lin, Vietnam Veterans Memorial (detail), 1982, granite, National Mall, Washington, D.C. (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

But progress had been made. In a blind competition of 1,400 entries, a young Asian American woman won the bid to design the national Vietnam War Memorial. Maya Lin’s design was something entirely new in war memorialization. It honored not generals or leaders or individual faces. Instead, it listed the name of every known individual who had lost their life in the controversial war.

With its abstract design and apolitical approach, the memorial symbolized the need for the nation to move beyond the conflicts of the 1970s, even if the root of those conflicts remained largely unresolved.