Asher B. Durand, Progress (The Advance of Civilization), 1853, oil on canvas, 58 7/16 x 82 1/4 x 4 3/8 inches (Virginia Museum of Fine Arts; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Lush vegetation, broad rivers, rich farmland, spectacular mountains. In the 19th century, the western part of what is now the United States held the imagination of U.S. citizens as a place of almost limitless possibility. This vision of the West’s abundant opportunity is celebrated in Asher B. Durand’s painting Progress—commissioned by a railroad baron (whose own fortunes were tied up with westward expansion). [1]

Train (detail), Asher B. Durand, Progress (The Advance of Civilization), 1853, oil on canvas, 58 7/16 x 82 1/4 x 4 3/8 inches (Virginia Museum of Fine Arts; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In the painting, we see canals, railroads, and steamships crisscross the landscape, and towns, and churches spring up, all bathed in the light of the sun. In the shadowed foreground on the left, a small group of Indigenous Americans, set in a dark primeval forest, look out at the gleaming promise of Euro-American progress. At the lower right, white settlers are shown having built a homestead—beginning the process of taming the wilderness.

Left: Indigenous people look on (detail), right: Settler homestead (detail); Asher B. Durand, Progress (The Advance of Civilization), 1853, oil on canvas, 58 7/16 x 82 1/4 x 4 3/8 inches (Virginia Museum of Fine Arts; photos: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

This was the essence of the once-broadly-held concept of Manifest Destiny: that the United States had a divine, “manifest” (self-evident) mission to create a nation that stretched from the Atlantic to the Pacific, spreading the light of democracy and the word of God.

Divine providence as symbolized by the sun (detail), Asher B. Durand, Progress (The Advance of Civilization), 1853, oil on canvas, 58 7/16 x 82 1/4 x 4 3/8 inches (Virginia Museum of Fine Arts; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Indigenous peoples, slavery, and the politics of geography

Even before the term Manifest Destiny was coined, the British colonists wanted to move west. In fact, they sought independence in part because of their frustration with Britain’s intent to honor its treaties with Indigenous allies (that barred British subjects from settling west of the Appalachian Mountains). [2]

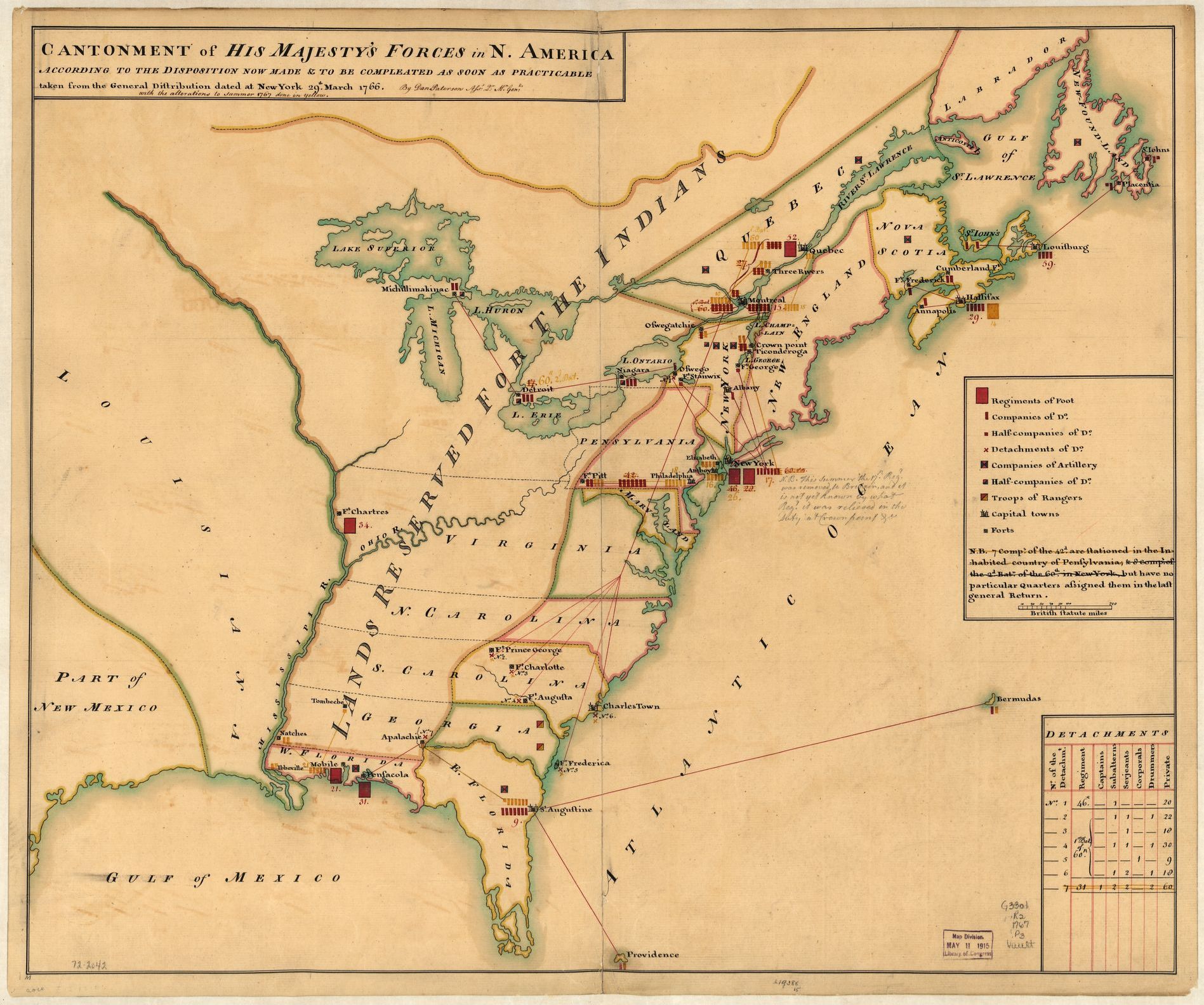

A 1767 map of the placement of British military forces in North America. Daniel Paterson, Cantonment of His Majesty’s forces in N. America according to the disposition now made & to be completed as soon as practicable taken from the general distribution dated at New York, 29th. March, 1767 (Library of Congress)

A map of the placement of British military forces in North America from 1767 directed that lands between the British colonies on the eastern seaboard and the inland French territory of Louisiana were “reserved for the Indians.” Victory in the American Revolution gave citizens of the new United States license, as they saw it, to invade western lands and remove the Indigenous peoples there.

But what kind of nation would it be? At the same time that the United States was laying claim to enormous new territories—from the 1803 Louisiana Purchase to the 1848 Mexican Cession—the citizens of its existing states were becoming increasingly divided by region on the issue of slavery.

Slavery had existed in the 13 British colonies that would become the United States, but during the late 18th and early 19th centuries the geography of slavery began to shift. Northern states gradually outlawed slavery, often citing incompatibility with the principles of freedom and democracy espoused in support of the American Revolution.

Susan Anne Livingston Ridley Sedgwick, miniature portrait of Elizabeth Freeman (Mumbet), 1811, watercolor on ivory, 7.5 cm x 5.5 cm (Massachusetts Historical Society)

As an example, Elizabeth Freeman successfully sued for her own freedom (in the case Brom and Bett v. Ashley, 1781) arguing that the state’s Bill of Rights guaranteed her freedom and equality. As a result, Massachusetts became the only state in the Union to end slavery because it was declared unconstitutional by a court. Here we see Freeman portrayed in watercolor on a precious piece of ivory. She looks directly at the viewer with a gently critical gaze. Her hair, just visible under her bonnet, has turned white, and her age is also expressed through the lines on her face. This fierce advocate for the abolition of slavery appears both alert and riveting.

Southern states, by contrast, passed laws further restricting the lives of enslaved people after the American Revolution. For example, numerous southern states passed anti-literacy laws that made it illegal for enslaved people to read or write (an enslaved person who was literate was perceived as more threatening). These repressive measures were taken just as white citizens became more and more dependent on enslaved people as laborers and as capital. It is important to note, however, that the northern states also profited from slavery. As late as the 1850s, the labor of the enslaved powered profitable northern textile mills and the New York Cotton Exchange. Nevertheless, by the mid-19th century, opinions on slavery in northern states and southern states had largely diverged.

The promise of the “West” crystallized these competing views. In the white imagination, the “West” encompassed any land beyond the Appalachian mountains (not limited to the present-day borders of the United States). White farmers from northern states feared that wealthy slaveholders would dominate the West and limit their opportunities there. Enslavers, on the other hand, feared that if slavery was barred in the West, their profitable system and the culture built upon it would soon wither and die. Neither side spared much thought for the people who already lived on the lands such as Indigenous people, Mexican Americans, or Californios, onto which these white people projected these hopes and fears.

Over the course of the 19th century, westward migration and the establishment of American settlements with and without slavery pushed Indigenous and Hispanic peoples off of their lands, and fueled the flames that would erupt in the Civil War.

Slavery and westward expansion

Who moved west, and why, differed by region. White northerners (who were increasingly less likely to own enslaved people as the 19th century progressed) moved westward to establish small farms. White southerners also moved westward in search of new land that might support ranching or large-scale agriculture—for example, cotton cultivation. Those southerners who owned enslaved people often sent them ahead to clear this new land, and to extend the plantation system westward.

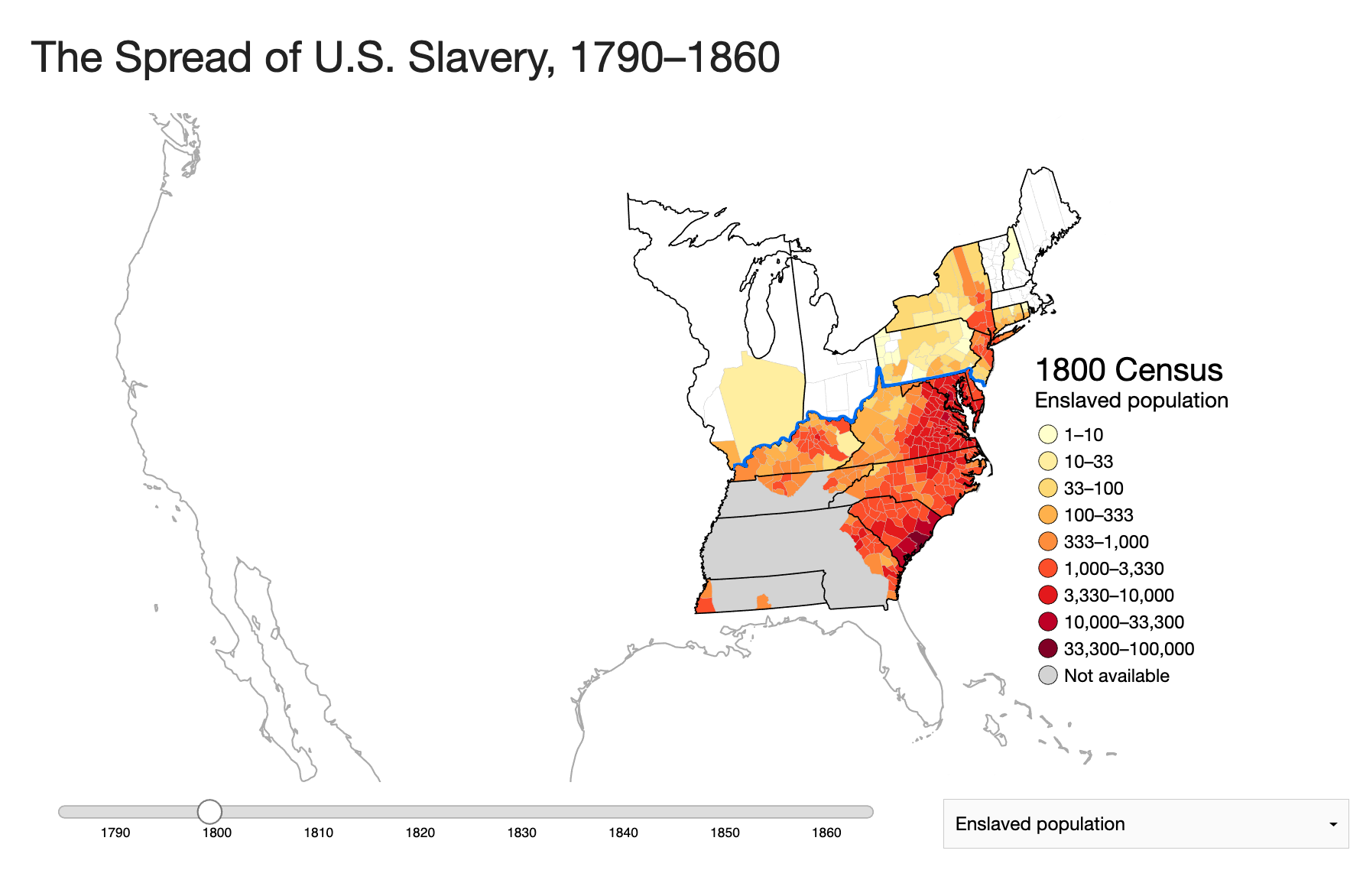

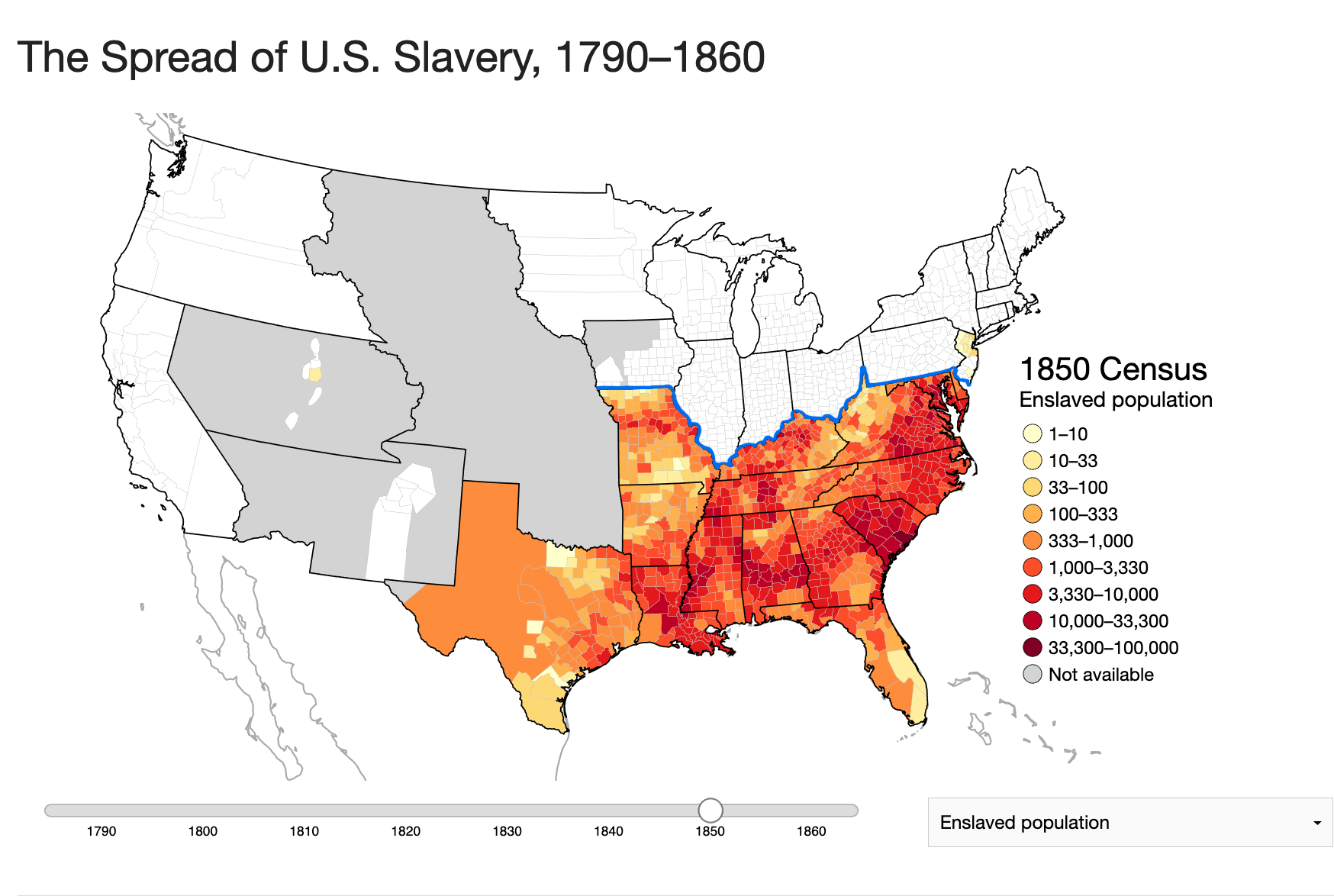

Maps credit: Lincoln Mullen, “The Spread of U.S. Slavery, 1790–1860,” interactive map, doi: 10.5281/zenodo.9825, Minnesota Population Center, National Historical Geographic Information System: Version 2.0 (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, 2011). Note that census data is incomplete and likely underestimates the enslaved population (along with the population as a whole).

The two maps above illustrate how slavery changed over time as the United States expanded westward: in 1800, there was a significant population of enslaved people in northern states (those above the blue line) and an even larger enslaved population concentrated along the coasts of the southern states. By 1850, slavery was nearly gone in northern states (including the new states to their west). In contrast, the number of enslaved people both increased and spread in the southern states (including the new states to their west).

Free states, slave states

The political imperatives of slavery were baked into the very framework of the United States. After much debate, the framers of the Constitution agreed to allow states to count three-fifths of their enslaved population toward their total population, even though enslaved people lacked citizenship rights. This was important because representation (and therefore voting power) in the legislative branch of the U.S. government was tied to the number of states and the size of their populations. New states got equal voting power with existing states in the upper house of the legislature (the Senate), and states with higher populations had more votes in the lower house (the House of Representatives). Therefore the question of whether new states would permit slavery was highly charged as it would permanently alter the balance of power between free and slave states.

With the Louisiana Purchase in 1804, the United States nearly doubled in size. Less than two decades later, and as a result, the question of slavery in states carved out of new territories became one with lasting political consequences. More states where slavery was permitted meant more pro-slavery senators, perhaps eventually enough to control the government and make slavery legal everywhere. The opposite was also true: if abolitionist sentiment grew along with the northern population and the number of free states, anti-slavery politicians might gain control of government and strip enslavers of their valuable human property.

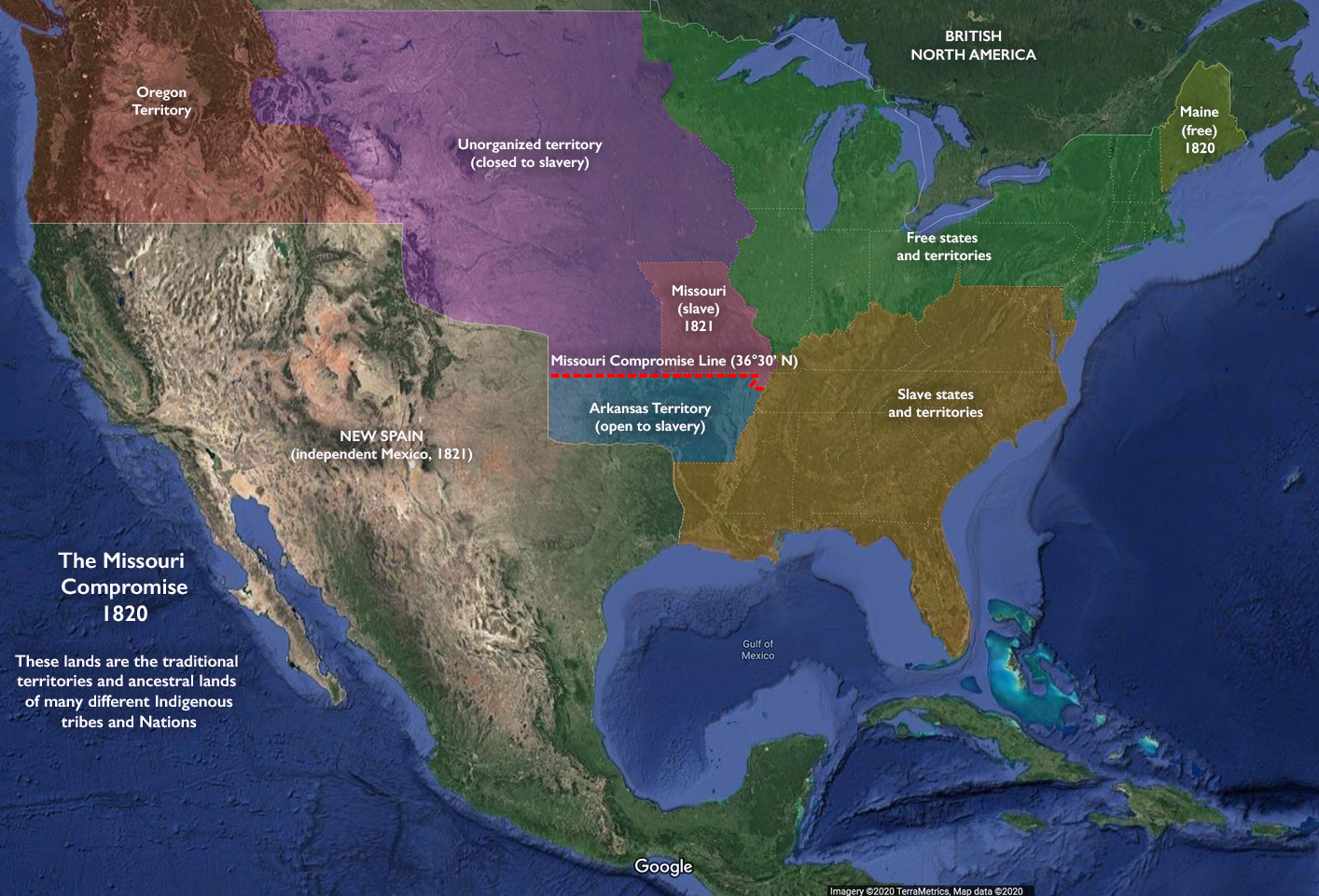

Map depicting U.S. states and territories in 1820. The Missouri Compromise admitted Maine as a free state, and then permitted Missouri to organize as a slave state, drawing a line across Missouri’s southern border above which slavery would not be permitted in the unorganized territory (underlying map © Google)

Expansion, crisis, and war

With so much riding on the balance of power, there were several crisis points in the 19th century as new states joined the Union. The first was the Missouri Crisis of 1819, when the residents of the territory of Missouri (formed on land gained in the Louisiana Purchase) requested an enabling bill from Congress to begin the process of statehood. A House representative from New York proposed an amendment that would provide for gradual emancipation in Missouri, but southern representatives reacted angrily to the amendment, threatening secession. It took months for Congress to work out the “Missouri Compromise”: that Missouri would enter the Union as a slave state at the same time that Maine entered as a free state, and slavery would be banned in the rest of the Louisiana Purchase territory north of Missouri’s southern border.

But the Missouri Compromise did nothing to solve the underlying problem, and slavery continued, with the nation bitterly divided over its future. To avoid repeating the crisis, new “free” and “slave” states were admitted more or less in pairs in the succeeding decades: Arkansas and Michigan, Florida and Iowa. Congress sat on the Republic of Texas’s request for annexation for nearly a decade to avoid stirring up sectional tensions. It was only after the ardent expansionist and slaveholder James K. Polk took office as president in 1845 that the United States moved forward with claiming Texas. The U.S. also provoked a war with Mexico in 1846 in an effort to gain Mexican territory and the valuable Pacific ports of California.

George Caleb Bingham, Country Politician, 1849, oil on canvas, 51.8 x 61cm (de Young Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

As with the Missouri Compromise, a firestorm erupted in Congress early in the Mexican-American War when David Wilmot, an anti-slavery Democrat from Pennsylvania, introduced an amendment to a military appropriations bill in Congress. This “proviso” proposed to outlaw slavery in any territory that might be gained from Mexico in the ongoing war. George Caleb Bingham was a painter, a Whig, and a member of the Missouri House of Representatives. His canvas, Country Politician was first exhibited as Congress debated Wilmot’s amendment. Bingham depicts a politician (at right) earnestly addressing an older voter (at left), perhaps to persuade him to support the Wilmot Proviso. The artist here focuses on the political choices that citizens faced, including slavery and its future.

During the 1850s, disputes over the fate of slavery in the new western territories raged in Congress and among the general public. The Gold Rush in California in 1849 hastened immigration to the West. The most serious political conflicts over slavery, however, took place in the Great Plains region. Violence erupted when the existing ban on slavery north of the Missouri Compromise line (see map above) was overturned in favor of the doctrine of “popular sovereignty,” which allowed territories to decide for themselves whether or not to allow slavery. This resulted from the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which also stripped the Indigenous residents of their land rights and opened the territory to settlers. Thousands of armed pro- and anti-slavery settlers poured into the Kansas Territory to influence whether it would be free or would allow slavery. Dozens died in the skirmishes that followed, a period known as Bleeding Kansas.

Opposition to the Kansas-Nebraska Act brought anti-slavery members of the Democratic and Whig parties together to form a major new national party, the Republican Party, which opposed the extension of slavery into the West. When Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln won the presidential election in November of 1860, slaveholders feared that their enemies had secured the political power to defeat them at last. In December of 1860, slave states in the deep South began to secede in anticipation of potential legislation to limit slavery. The Civil War began shortly thereafter.

What was it about the West that so captivated white Americans that they went so far as to shed blood to determine its future? All sides envisioned using the West’s resources—fertile land for farming and grazing, abundant forests for timbering and trapping, rich mines for extracting mineral wealth—for their own gain.

William S. Jewett, The Promised Land—The Grayson Family, 1850, oil on canvas, 50 3/4 x 64 inches (Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection)

Andrew Jackson Grayson, whose family was among the earliest U.S. settlers to move to California in 1846, commissioned this painting of their arrival in 1850. Grayson dictated many of the painting’s details to the artist, William S. Jewett, including the clothing and the site in the Sierra Nevadas, where he claimed that they had first laid eyes on the plains of California. The painting’s Biblical overtones—its name, The Promised Land, recalling the prophet Moses, and its richly dressed family of three evoking the Holy Family—reinforced the Manifest Destiny notion that God sanctioned white settlement of the West (where a diverse population of Indigenous and Hispanic people already lived). The painting depicts California empty of people, erasing the region’s inhabitants whom white settlers persecuted and murdered as they sought control of the land. Grayson himself joined the fighting in the Mexican-American War (which would wrest California from Mexico), as part of the California Battalion, led by the explorer and army officer John C. Frémont.

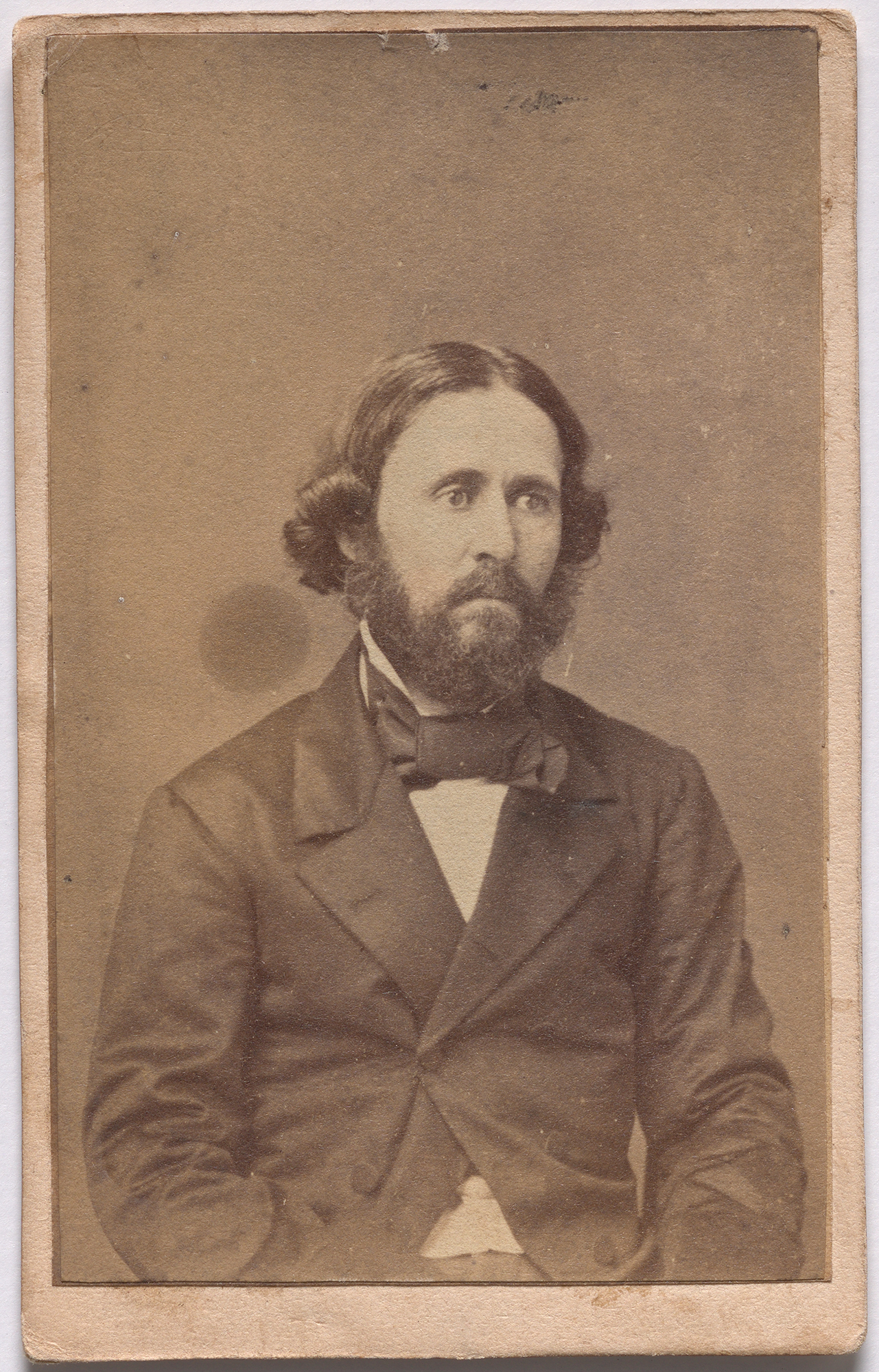

Meade Brothers Studio, John Charles Frémont, c. 1856, photograph, 9.2 x 5.7 cm (National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution)

Frémont and violence against Native Americans

Frémont would become California’s first Senator. He held an anti-slavery position, but also had a near total disregard for Indigenous people and their cultures, typical of white people at this time. He led several massacres against Indigenous people, including the Sacramento River Massacre (1846), in which he and his men killed at least 120 Wintu men, women, and children (with some estimates of the dead as high as 700). Frémont directly supported the ideology of Manifest Destiny—through his violence against the Native populations of California, and by encouraging settlers in California to revolt against the Mexican government. In 1846, whites did in fact briefly establish the California Republic (in a move similar to the Texas Revolution a decade earlier), eventually ceding control of the region to U.S. Army forces. Despite his aggression toward Native Americans and the Spanish, Frémont was a fierce anti-slavery politician, and in 1856, he became the first Republican presidential candidate.

![Solomon Nunes Carvalho, [View of a Cheyenne village at Big Timbers, in present-day Colorado, with four large tipis standing at the edge of a wooded area. Frame with pemmican or hides hanging at the right; two figures, facing camera, standing to the left of center], between 1853 and 1860, daguerreotype (Library of Congress)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/service-pnp-cph-3c10000-3c10000-3c10000-3c10045v-e1643402092706.jpeg)

Solomon Nunes Carvalho, [View of a Cheyenne village at Big Timbers, in present-day Colorado, with four large tipis standing at the edge of a wooded area. Frame with pemmican or hides hanging at the right; two figures, facing camera, standing to the left of center], between 1853 and 1860, daguerreotype (Library of Congress)

Beyond the West: Latin America and the quest for new slave states

Proslavery expansionists also attempted the military takeover (called filibustering) of some Latin American countries, whose warm climates were suitable for plantation agriculture. Some of the regions already had systems of slavery, making them excellent candidates for an expansion of U.S. slavery.

For example, in the early 1850s, U.S. citizen William Walker led an illegal war with Mexico to create independent slaveholding republics, including the Republic of Lower California in what is today northern Mexico. An American jury acquitted Walker for violating the Neutrality Act of 1794, which barred American citizens from waging war against any country at peace with the United States. In 1856, Walker launched an invasion of Nicaragua, and took control of the country for nearly a year before a coalition of Central American armies removed him from office.

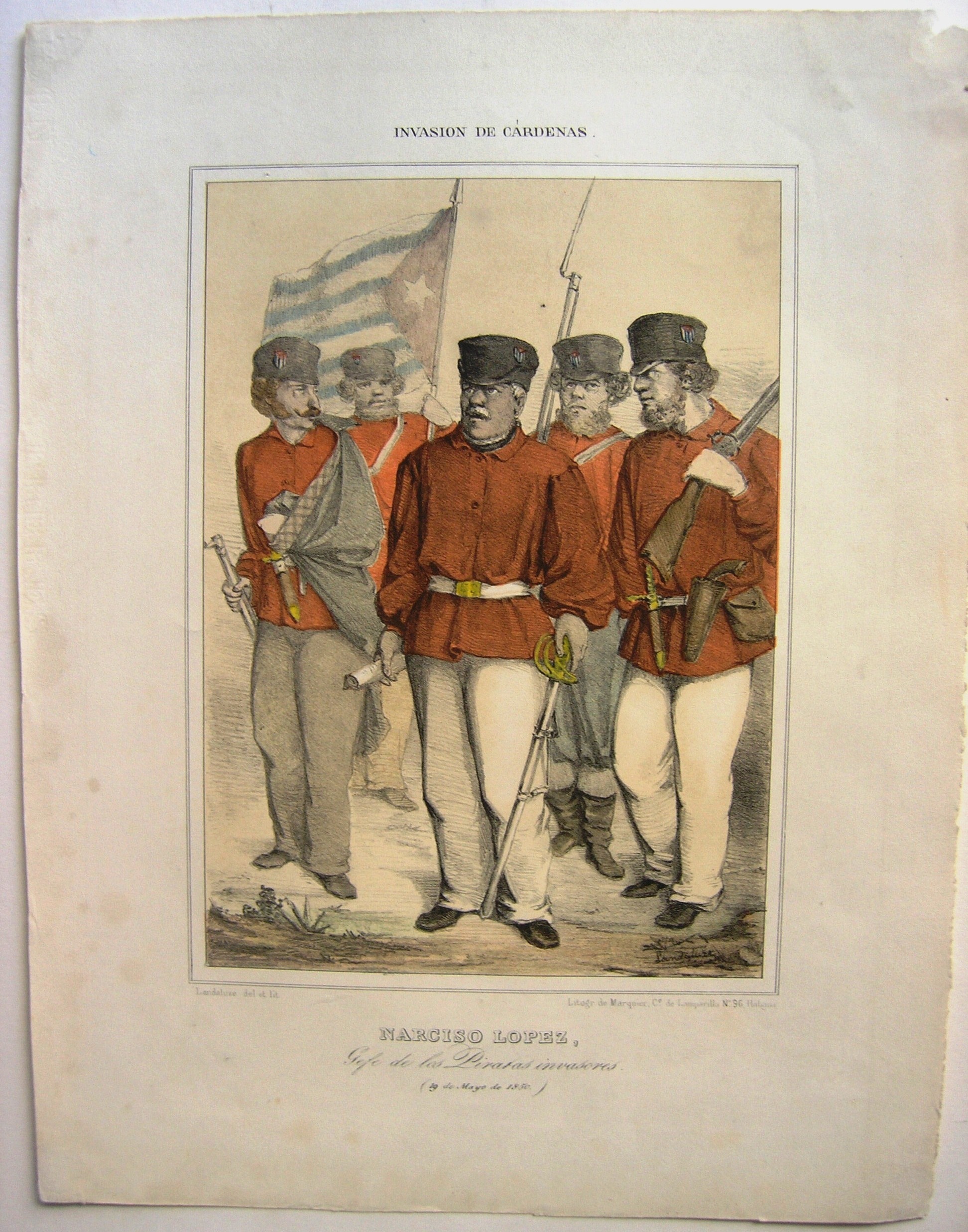

Narciso López, Gefe de los Piratas Invasores (Leader of the Invading Pirates), 19 de Mayo de 1850, 1850; color lithograph by Marq, lithographer; Víctor Patricio de Landaluze, draftsman (The Historic New Orleans Collection). This lithograph was part of a series depicting López’s attempt to invade Cardenás, Cuba, as part of a scheme of U.S. annexation.

Similarly, between 1848 and 1851 Cuban exile Narciso López, who was financed by U.S. sugar growers (an industry reliant on slave labor), organized several filibustering expeditions to Cuba, which was then controlled by Spain. He aimed to expand U.S. sugar production to Cuba, where slavery was legal, and to add Cuba to the U.S. as yet another slave state. In the lithograph above, López is depicted leading a group of armed men in the Cuban town of Cardenás. They are flying a flag that independent Cuba would adopt as its own in 1902. During López’s final Cuban campaign, he was captured and executed along with dozens of U.S. citizens who had attempted to take the island from the Spanish.

The expansionist mindset

Although the stories of the failed states that William Walker and Narciso López pursued may seem like a detour from the story of U.S. westward expansion, they illustrate the breadth of the expansionist mindset. Today, the territorial boundaries of the greater United States (as well as those of the individual states within it) may seem inevitable and fixed, but when U.S. citizens looked beyond their established borders in the mid-19th century, they saw possibility in many directions. There could be many dozens of new states west of the Appalachian Mountains and south of Texas. There could be—and eventually would be—American territories and states on Pacific islands, Caribbean islands, and the far north. The whole western hemisphere might be up for grabs.

With these wild opportunities came fears on both sides. Each new state in the Union meant one side or the other accrued more power in government and more influence on the future of American society. It was only in 1860, when the election of an antislavery president demonstrated that enslavers had lost the game of states for good, that they turned to warfare.

Notes:

[2] This was the Proclamation of 1763.

Additional resources

Learn more about Asher B. Durand at The Met.

See lesson plans about Manifest Destiny at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Amy S. Greenberg, A Wicked War: Polk, Clay, Lincoln, and the 1846 U.S. Invasion of Mexico (New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2012).

Learn more about Solomon Nunes Carvalho’s expedition photographs at the Library of Congress.