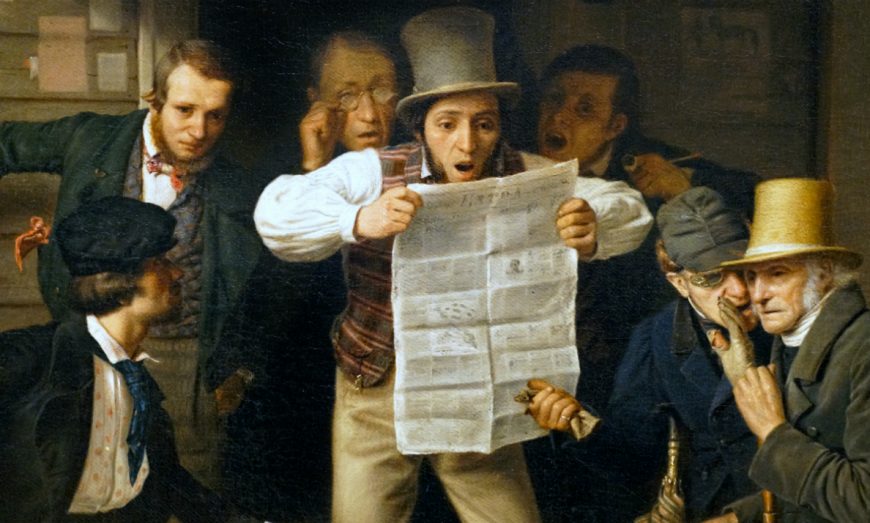

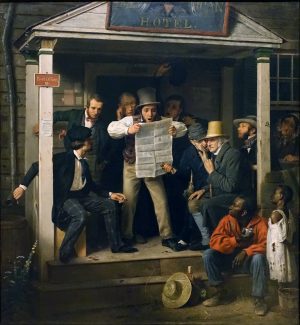

Opinion on the war was with Mexico was divided and Woodville therefore depicted a range of responses among the figures reading the latest news in a Western outpost. Detail, Richard Caton Woodville, War News from Mexico, 1848, oil on canvas, 68.6 × 63.5 cm (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art). Watch the video.

A forgotten war with unforgettable consequences

A tourist visiting the National Mall in Washington, D.C. today is likely to see monuments commemorating American involvement in several foreign wars, including the striking Vietnam Memorial, with its reflective surface naming the war dead, or the squadron of stainless steel soldiers honoring veterans of the Korean War. That same tourist might be surprised to learn that the United States had fought another foreign war whose toll on the American population was greater than either of those conflicts: the Mexican-American War (1846–1848). [1]

Maya Lin, Vietnam Veterans Memorial, 1982, granite, National Mall, Washington, D.C. (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

There is no memorial to the Mexican-American War in Washington, D.C., and only about 30 monuments across the whole of the United States pay tribute to a war in which more than 15,000 American soldiers lost their lives. By comparison, there are at least 13,000 historical markers commemorating the U.S. Civil War. [2] In fact, the Mexican-American War has been overlooked in both U.S. and Mexican popular culture. The war is rarely depicted in film, and no images of the War of Northern Invasion (as the war is named in Mexico) were made by Mexican artists. A war of conquest conducted by a land-hungry U.S. government against ill-supplied Mexican soldiers did not generate much pride for either nation.

Timeline of significant events

Nevertheless, the Mexican-American War had far-reaching consequences for both the United States, Mexico, and the Indigenous peoples whose land both nations claimed. First among these was the cession of about one third of Mexico’s territory to the United States, a landmass of over 338,000,000 acres. Redrawing the border added to American economic prosperity at Mexico’s expense. The war also contributed to the outbreak of later civil wars in both countries: the Civil War in the United States (1861–1865) and the War of Reform in Mexico (1857–1860).

Lastly, the war’s outcome left many residents of the ceded territory worse off than they had been under Mexican rule, which had guaranteed people of African and Indigenous descent some rights and protections. Not only did the U.S. government permit slavery (which had been outlawed in Mexico for years) but the annexation of these lands sent large numbers of white American settlers west, where they displaced and often killed Indigenous people.

Comparing Mexican and American societies before the war

Both the United States and Mexico were young republics that had recently gained independence after centuries of European colonization. The process had been considerably easier for the United States, which had had French aid in defeating Great Britain, as well as bountiful natural resources to fuel its economy. In the early nineteenth century, the people of the United States were awash in patriotism, Protestant religious fervor, and enthusiasm for rapid expansion. Jacksonian Democracy, ushered in by the presidency of Andrew Jackson, extolled the virtues of the “common man,” extending the franchise to all white men regardless of their social standing.

George Caleb Bingham portrayed the Missouri election in which he was running as a candidate for state legislature (he depicts himself at center, seated on the wooden steps). Bingham seems both to celebrate and critique the enthusiastic exercise of mid-nineteenth century U.S. democracy, depicting the white male voters with equal dignity, although he shows some men who are clearly inebriated. George Caleb Bingham, The County Election, 1852, oil on canvas, 38 x 52 in. (96.5 x 132.1 cm) (Saint Louis Art Museum).

But citizenship in the United States became more entwined with constructions around racial difference at the same time it became less tied to class. The “white man’s republic” championed by Jacksonian Democrats categorically excluded women and people of color from the body politic. This was particularly evident in Jackson’s policy of “Indian Removal”: where once white Americans had committed to christianize and assimilate Indigenous people for their own good, many now declared Indigenous people savages who must either be expelled to distant western lands or face extinction.

By contrast, Mexico had won independence after 300 years of Spanish colonization without outside help, but the conflict had left the nation in a difficult economic state, with its mining, industrial, and agricultural capacity significantly reduced. The Mexican government was unstable, with 50 different governments in the 30 years after independence, most installed by military coup. Conservatives wanted to maintain a version of the colonial system that privileged social elites, the army, and the Catholic Church, while Liberals wanted to implement republican reforms.

Although Mexican society did make sharp distinctions of race and class in the years leading up to the war, nonwhites had more political power and social mobility than in the United States. Centuries of racial and cultural mixing between the descendants of Spanish settlers, enslaved Africans, Indigenous inhabitants, and Asian immigrants of the region had created a diverse populace. After independence from Spain, the Mexican government removed racial identifiers from official documents to promote equality in the new republic, and in 1829 abolished slavery altogether.

Cotton, Texas, and Manifest Destiny

Many Americans believed that the key to their prosperity was relentless expansion. The U.S. government had purchased the Louisiana Territory in 1803, and newspaper editors spread the idea that it was the “Manifest Destiny” of the United States to possess North America from the Atlantic to Pacific Ocean. The ideology of Manifest Destiny justified U.S. imperialism by claiming that the nation had a divine mission to spread democracy and Protestant Christianity across the continent.

Expansion was particularly crucial for the cotton planters who dominated the southern United States. Cultivating cotton quickly depleted soil, and plantation owners were eager to obtain more fertile land. They relied on the forced labor of enslaved people of African descent, and sought to expand slavery along with the borders of the American south. Many cotton planters crossed the border into the Mexican territory of Coahuila y Tejas, where they were initially welcomed as a stabilizing force that would help to repel raids from the powerful Comanche (Nʉmʉnʉʉ) nation. But the Mexican government soon grew frustrated with the American settlers, who disregarded the ban on slavery and showed no intention of assimilating into Mexican society.

The war begins

In 1836, American and Mexican residents who wanted to introduce enslaved laborers to the area to farm cotton took advantage of the Mexican government’s tenuous hold on the country’s periphery by declaring Texas an independent republic. The Texians triumphed, despite their storied defeat at The Alamo, a Spanish mission (San Antonio de Valero) that had been converted into a fortress. But the Mexican government did not accept the treaty granting Texas independence since it had been signed under duress. For nearly ten years, the Mexican government considered Texas a rebel territory, while the United States recognized it as a sovereign nation.

In fact, Texians wanted to join the United States and applied for annexation shortly after the rebellion. But the U.S. Congress, unwilling to upset the delicate balance between states that permitted slavery (“slave states”) and states that did not (“free states”), declined to consider the matter. All of that changed when James K. Polk was elected president in 1844. Polk was a Democrat, closely tied to Andrew Jackson, and he favored territorial expansion. Consequently, the United States annexed Texas in 1845 (leading Mexico to sever diplomatic relations), and Polk negotiated with Britain for a portion of the Oregon Territory in 1846.

Polk also sent an envoy to Mexico to offer to purchase California, then coveted for its Pacific ports and fertile farmland, but the Mexican government refused. Finally, in April 1846, Polk sent U.S. soldiers under the command of General Zachary Taylor to disputed territory south of the Nueces River, hoping to provoke conflict.

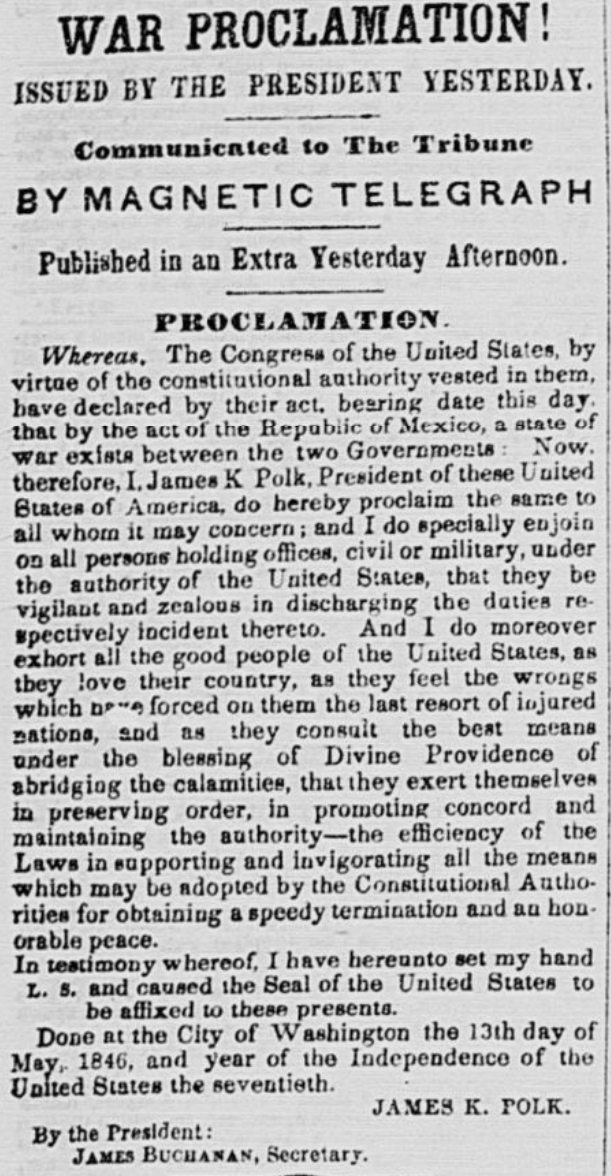

Text of Polk’s war proclamation in the New-York Daily Tribune (Library of Congress).

The progress of the war

Polk’s gamble paid off; after a U.S. patrol marched into the disputed territory, a Mexican cavalry unit attacked, killing 11 American soldiers. When news reached Washington, D.C. two weeks later, Polk went to Congress to ask for a declaration of war, claiming that Mexico had shed “American blood on the American soil.” Many U.S. lawmakers, especially those of the opposition Whig party, were suspicious of Polk’s claims—Abraham Lincoln, then a young Congressman, would later ask the president for evidence of the exact “spot” where the hostilities had begun—but conscious that fighting was already underway, the Whigs ultimately voted to support the war.

Detail of map below, showing land and naval campaigns during the Mexican-American War, including Monterrey and Buena Vista.

General Taylor commanded just one of many American military forces in what would become a two-year-long, multi-front war. In northern Mexico, Taylor fought inland to Monterrey and secured the region for the United States in the Battle of Buena Vista.

Farther north (see map below), the U.S. army captured Santa Fe, in what is now New Mexico, without firing a shot (although Mexican and Indigenous Puebloan residents later rebelled against U.S. occupation in the Taos Revolt). Naval campaigns targeted the west coast of Mexico from Mazatlán to Yerba Buena (present-day San Francisco), and wrested control of the ports and pueblos of California along with several ground units.

Map of land and naval campaigns during the Mexican-American War. The inset depicts General Winfield Scott’s route from Veracruz to Mexico City (map: Kaidor, CC-BY-SA 3.0).

The most devastating campaign, however, was in southeastern Mexico (see inset in map above). In 1847, U.S. General Winfield Scott conveyed a force of more than 13,000 men by sea to Veracruz. He deliberately followed the same path of conquest to Mexico City that Hernán Cortés had taken more than 300 years earlier to the Mexica capital of Tenochtitlan (which became Mexico City). In September 1847, the U.S. army invaded the nation’s capital, Mexico City. Despite months of guerrilla warfare, Mexicans could not expel the occupying army.

In February 1848, the two nations negotiated the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo to end the war. The treaty’s terms gave the United States most of what is now the southwestern United States, including the modern-day states of Texas, California, Utah, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, and portions of Colorado and Wyoming, in exchange for $15 million and the forgiveness of Mexican debts to American citizens. Mexicans who chose to remain in the territory would receive American citizenship.

“A wicked war”

“I do not think there was ever a more wicked war than that waged by the United States on Mexico.” —Ulysses S. Grant, 1879

Ulysses S. Grant, who would go on to command the victorious forces in the Civil War nearly twenty years later, not to mention serve as president of the United States, was a 24-year-old lieutenant during the Mexican-American War. Grant believed that in the Mexican-American War, a stronger nation had unjustly made war on a weaker one. [3] Indeed, the United States government had expected a quick win against an inferior opponent, and the extent of Mexican resistance came as a surprise. Racial and religious prejudice influenced American attitudes toward Mexicans. Officers wrote about the depredations committed by volunteers, who frequently stole from and sometimes killed Mexican civilians.

Most American soldiers and volunteers were Protestants, rife with anti-Catholic prejudice, and they disdained Mexican religiosity as superstition and ignorance. In some cases, American soldiers deliberately defiled churches or religious objects. Their behavior so disgusted German and Irish Catholic volunteers that several hundred switched sides and fought for the Mexicans as the St. Patrick’s Battalion, or San Patricios.

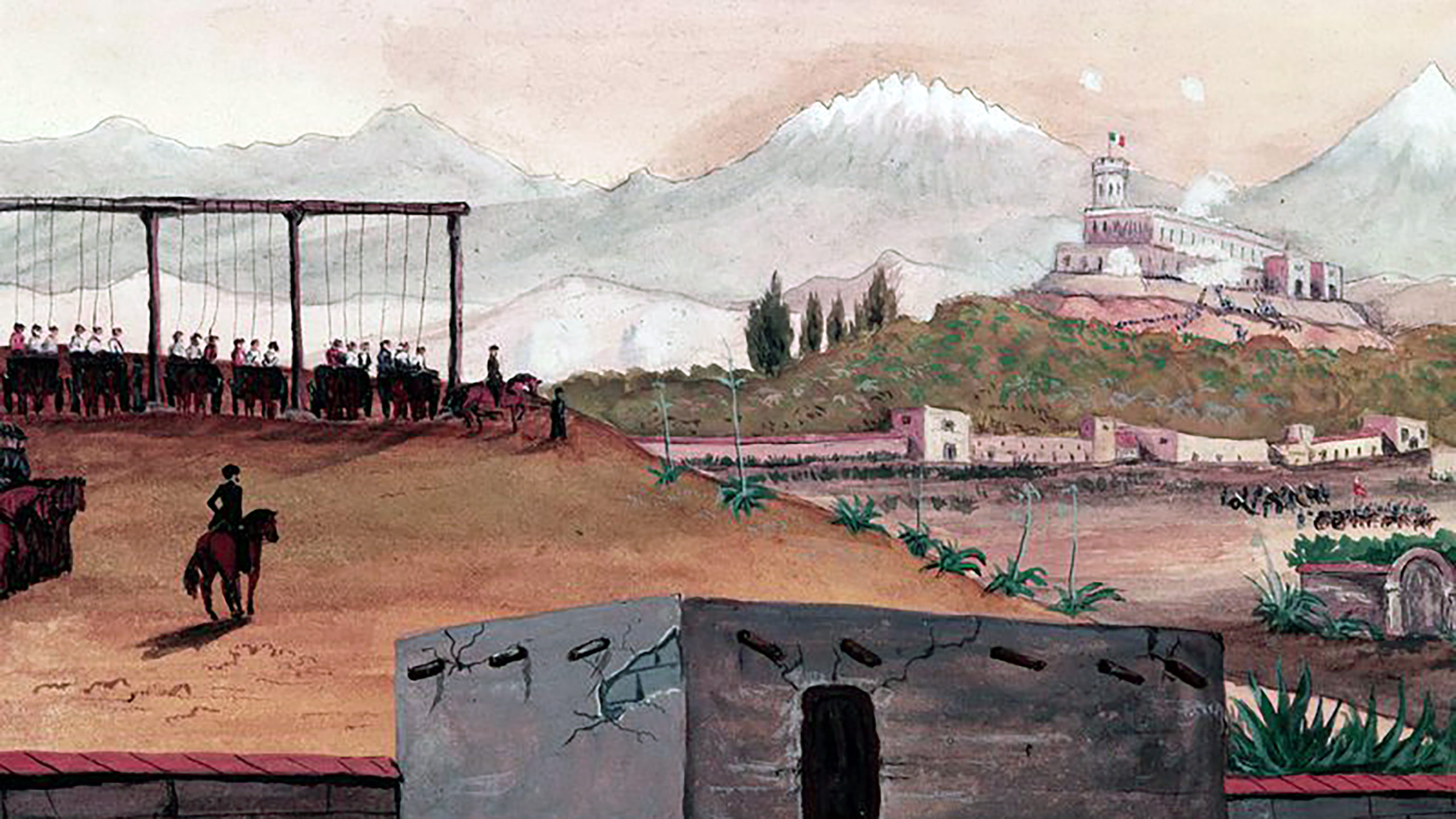

The San Patricios were U.S. soldiers who switched sides to fight with the Mexican army. Many were captured and executed in the battles leading up to the occupation of Mexico City. Samuel Chamberlain, who was a private in the U.S. army during the 1847 mass execution, illustrated the event in his memoirs twenty years later. Chamberlain likely made sketches on site (suggested by the recognizable volcanoes in the Valley of Mexico and Chapultepec Castle in Mexico City at right) and worked them into finished watercolors at a later time. The hanging scene’s distance from the viewer, and the lack of visible emotion with which Chamberlain portrays it, suggests that he saw the San Patricios as traitors. Samuel Chamberlain, Hanging of the San Patricios following the Battle of Chapultepec, c. 1867, watercolor (Smithsonian Magazine).

Unknown photographer, General Wool and staff in the Calle Real, Saltillo, Mexico, c. 1847 (Amon Carter Museum of American Art)

New technologies of communication and representation brought news of the war home to civilians faster and more vividly than ever before. The first photographs of war anywhere in the world emerged from this conflict: a series of 50 daguerreotypes, now housed at the Amon Carter Museum, which were created in 1847 by an unknown photographer in Saltillo, Mexico. Daguerreotypists followed the U.S. troops, taking portraits of officers, landmarks, and grave sites as souvenirs. [4] The Mexican-American War was also the first war in which U.S. journalists accompanied the army as foreign correspondents, and the updates they sent home to newspapers by telegraph generated great interest and patriotism among the public.

Richard Caton Woodville, War News from Mexico, 1848, oil on canvas, 68.6 × 63.5 cm (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas)

But the war and its expansionist aims did not enjoy universal support in the United States. Just three months into the conflict anti-slavery politicians introduced a bill into Congress, the Wilmot Proviso, that would outlaw slavery in any territory that might be gained from Mexico.

In addition, the first anti-war movement in the United States arose in response to the conflict; many northeastern intellectuals protested what they saw as an unprincipled land-grab aimed at increasing the power of slaveholders. Henry David Thoreau, a leading Transcendentalist writer, was jailed for refusing to pay taxes to support the war. His essay on the duty of citizens to refuse to cooperate with immoral government actions, “Civil Disobedience,” inspired the nonviolent resistance tactics of later civil rights leaders, including Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr.

Consequences of the Mexican-American War

The war’s human cost is difficult to quantify. Historians estimate that 25,000 Mexican soldiers died, as well as 15,000 American soldiers. The vast majority of American men died from disease, not battlefield injuries, as the volunteer soldiers failed to implement necessary measures for sanitation. As many had feared, the addition of land suitable for cotton farming meant the extension of slavery, along with the human misery of the enslaved men and women who cleared and farmed the land. White settlers who moved to the west did not respect the rights of the Indigenous people or Mexican-Americans (those who had received U.S. citizenship at the war’s end) living there, often forcibly removing them from their land.

The political and social consequences of the war are easier to see. For Mexico, the defeat demonstrated the weakness of the country. Debates over the proper role of the army and the Catholic Church in politics led to the Reform War, and later the installation of a French emperor in Mexico. For the United States, the acquisition of western lands proved both a blessing and a curse. Their rich resources, including the gold discovered in California just weeks before the end of the war, contributed to growing American economic power. But the addition of new territory upset the fragile balance of power that had kept free and slave states bound together in an uneasy union. In 1861, the tensions over the expansion of slavery into the west led to the U.S. Civil War.

Notes:

- War dead as a percentage of total U.S. population. .057% of the U.S. population died as a result of the Mexican-American War.

- See the Historical Marker Database for estimates.

- For Grant’s quote concerning the “wicked war,” see John Russell Young, Around the World with General Grant (New York: American News, 1879), 2:447–48.

- James Oles, Art and Architecture in Mexico (Thames and Hudson, 2013), 155.

Additional resources:

View the text of the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo at the Library of Congress

See more Mexican-American War daguerreotypes from Google Arts & Culture

Political cartoons and prints relating to the Mexican-American War at the Library of Congress

Samuel Chamberlain’s Mexican-American War watercolors at the San Jacinto Museum