The Alamo, formerly part of Mission San Antonio de Valero, San Antonio, Texas (photo: Daniel Schwen, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Before the Alamo

Few places in the U.S. conjure as many images and legends about heroism and nationhood as the Alamo in San Antonio, Texas. The Alamo is an icon of American identity—like Gettysburg or Pearl Harbor—and as with these equally famous historic sites, our perception of the Alamo is malleable, as are the stories it purports to tell.

The site is firmly rooted in the popular imagination, having been the subject of countless works of literature, film, prints, paintings, cartoons, postcards, and even folklore. Long before it became an emblem of U.S. history though, the Alamo had been a Spanish mission that eventually became a ruin that was “repaired, rebuilt, and redefined.” [1] Yet a single event—the battle of 1836—overshadows the Alamo’s long and complex past. Today, visitors pay reverence to the Texians who died there while fighting the Mexican General Santa Ana—not to the holy Catholic saints who once filled the building’s niches nor to the Tejanos (Mexican settlers from Texas) who also died at the Battle of the Alamo. The current representation of the Alamo as the site of patriotic heroism and brave sacrifice eclipses Spain’s earlier colonial presence and the history of the site’s ruination, reconstruction, and reframing.

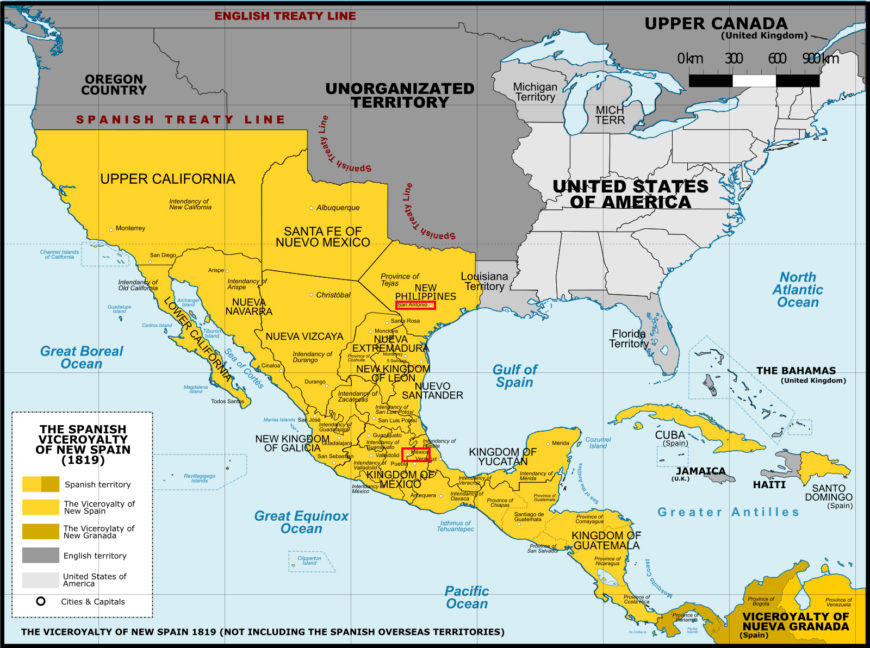

Map of the Viceroyalty of New Spain c. 1800, with Mexico City and San Antonio highlighted with red boxes

Mission San Antonio de Valero

Franciscan missionaries began to establish missions in what is today Texas beginning in the seventeenth century because this area was on the camino real (or royal road) that originated in the viceroyalty of New Spain’s capital, Mexico City. Forty missions originally dotted the Texan landscape, but only 9 survive today. None is more well-known than Mission San Antonio de Valero (which would later become the Alamo), established in 1718 on the west bank of the San Antonio River. Like the initial missionary centers constructed after the waves of conquest after 1521 in central Mexico, the San Antonio de Valero’s purpose was to convert local Indigenous people, including the Payayes, Ypanis, Xaranames, Zanas, and others. Soon after its establishment, the mission was moved across the river (to the east bank) and construction began in 1744 on a church (thought to be made of adobe) that would collapse. Construction eventually began on the stone and mortar structure that partially remains today. Adobe was a more common building material in this area, so the decision to use stone and mortar possibly associated the building with more Europeanized building practices (such as Spanish imperial buildings constructed in other parts of New Spain) and a clear deviation from local building types.

Lower half of the entry on the façade, Alamo/Mission San Antonio de Valero (photo: Noconatom, CC BY-SA 4.0)

An account in 1772 describes the building under construction as having a transept and cross-vaulted roof, complete with a dome. This building was never completed though. Friar Sáenz, who wrote the 1772 account, describes the façade as having scalloped-shell niches with sculptures of saints Dominic and Francis in them, each framed by solomonic (twisting) columns. Dominic and Francis are patron saints of the Franciscan and Dominican orders respectively—and were representatives of broader missionary efforts of the Spanish Crown. He notes the beauty of the façade and its carvings too. Decorative relief carvings also animated the rounded arch entryway on the façade.

Detail of the façade of the Alamo/Mission San Antonio de Valero (photo: David R. Tribble, CC BY-SA 3.0)

On the second level, St. Clare of Assisi and St. Margaret of Cortona (both female Franciscans) were to be carved and inserted into the niches (although descriptions cast doubt as to whether they ever were installed). A sculpture of the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception was intended for the central niche (but was never installed). The façade was originally flanked by two towers that, along with the barrel vault and the dome, collapsed circa 1762. Like most missions, the church was connected to a larger complex with a cloister, atrium, and more—today, only part of the church remains. The famous façade we know today was actually a chapel.

The Spanish conversion efforts involved in the missionary project in Texas, as elsewhere, involved dislocating, transforming, and converting local Indigenous communities, and the iconography of the façade may have played a role in this with its inclusion of saints associated with the evangelizing efforts of the Spanish Crown and religious orders.

An 18th-century retablo from New Spain; it is possible that the retablos that no longer exist looked something like this (albeit probably smaller). Main altar inside Santa Prisca y San Sebastián, gilded wood, plaster, Taxco, Guerrero, Mexico (photo: Javier Castañón, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Elaborate retablos (or altarpieces) once stood inside the mission as well. Unfortunately, they no longer remain and the sculptures once adorning them do not either (or were dispersed elsewhere without records that could tell us where they are now). Written inventories do list the images that once appeared on them. On the main altar, one apparently could have seen the Virgin of Sorrows, Saint Francis, Christ Crucified, John the Evangelist, Saint Clare, and Saint Joseph (among others). The wooden altarpiece was gilded, as was in style at the time, and retablos in churches like Santa Prisca and San Sebastián in Taxco, Mexico give us a sense of what this may have looked like.

Mission San José y San Miguel de Aguayo, founded 1720; restored in the 1930s (photo: Shiva Shenoy, CC BY 2.0)

The remains of the façade point to the classicizing forms employed by the architects of the church, including the rounded arch of the doorway flanked by niches. It is an adaptation of a Roman triumphal arch motif, which had become popular again during the Renaissance. In essence, it looks similar to a Roman triumphal arch in its design, and also had associations with power and conquest. It is interesting to consider this choice and its interpretation today. While such classical language was found at other missions, this was not the en vogue architectural language found in New Spain’s bigger and older cities, or even at other Texas missions (where ultrabaroque designs were preferred). It is possible that this more restrained, classicizing ornament was intended to call to mind visions of the early Church in its simplicity as well as its formation within the boundaries of the Roman Empire. With the initial waves of colonization, friars often modeled themselves and their built environment on the early church because they perceived it as purer and therefore more ideal.

Abandonment and transformation: The mission becomes the Alamo

Mission San Antonio de Valero was abandoned in 1793 when it was secularized—the first of the Texas missions where this occurred. Its altars were removed in 1824 and this is when many of its statues were relocated or lost. Most of the mission’s structures have also been lost. As noted earlier, the Alamo’s iconic façade that today graces tourist trinkets and postcards was actually the chapel attached to the larger mission church.

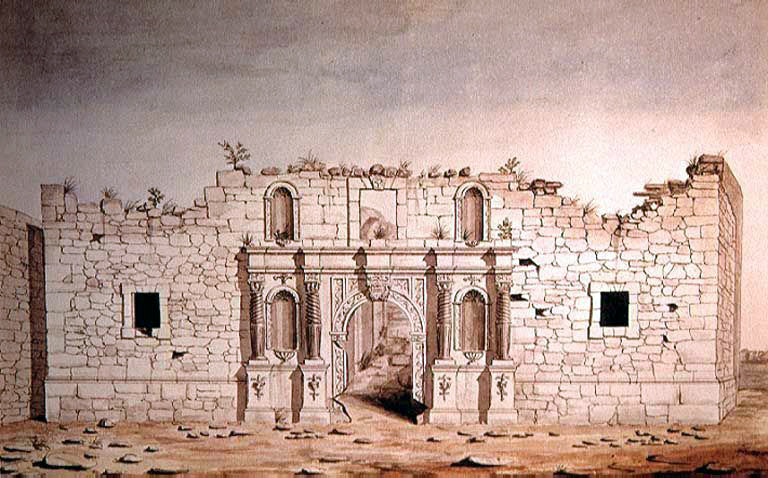

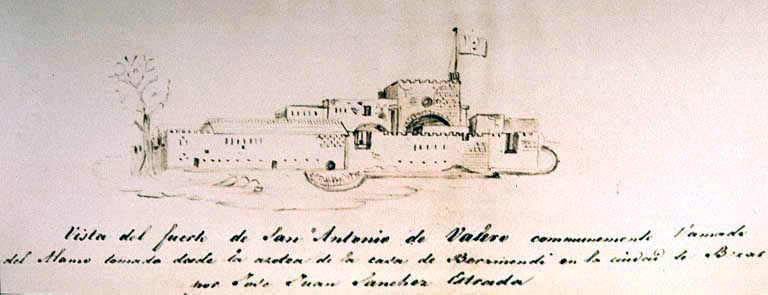

José Juan Sánchez Navarro, earliest known view of the Alamo, ca. 1835–36 (Western Americana Collection, Beinecke Library, Yale University)

The mission served as barracks for the Alamo Company (a military unit that came from Alamo de Parras, a town on the other side of the Rio Grande river, and which gave its name to the building we see today) and for the Mexican army until 1835, when Texians temporarily took the Alamo. It was at this moment that the famous battle involving the Mexican General Santa Ana occurred, in which Mexican troops defeated the Texians who sought independence from Mexico. The Mexican victory was brief; shortly thereafter Mexico would lose the war and Texas in the Mexican-American War. An early view of the Alamo by José Juan Sánchez Navarro shows how the artist envisioned the space as a fortified space, with turrets and tall, thick walls. It does not look like this any longer (if it ever really did).

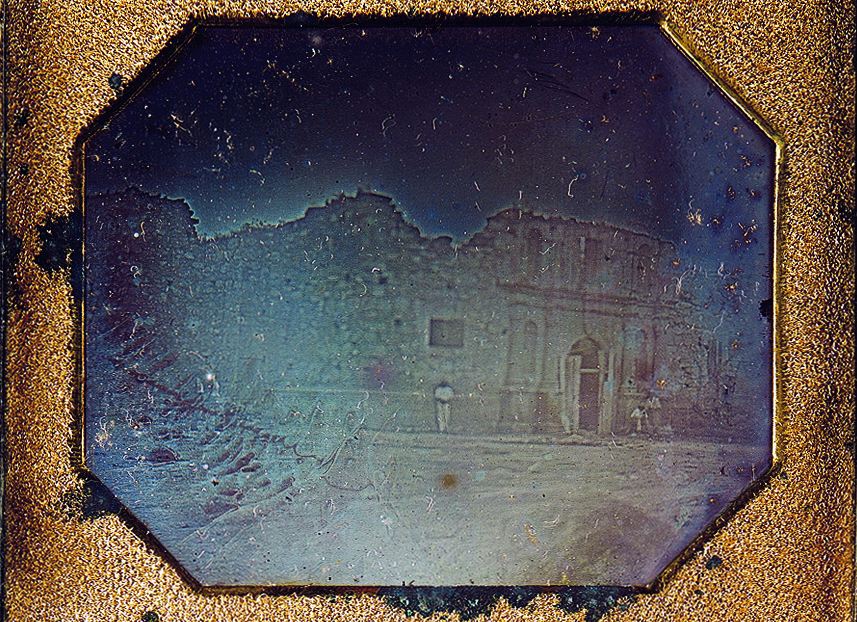

Earliest known photograph taken in Texas, 1849 daguerreotype, photographer unknown (Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin)

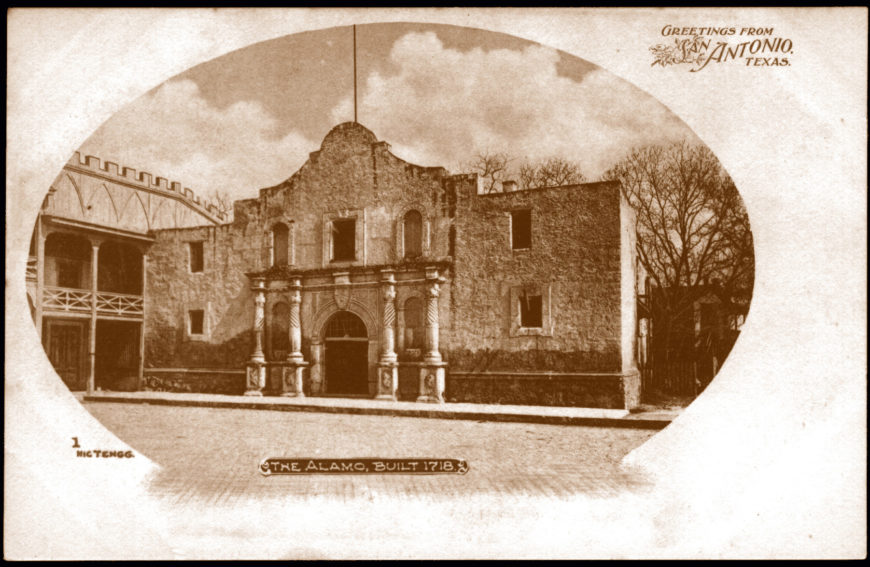

Throughout the nineteenth century, Mission San Antonio de Valero—now known as the Alamo—suffered neglect and vandalism. After the battle of the Alamo in 1836, most of what remained of the façade’s sculptures were gone, and the building was badly damaged, much of it rubble. After Texas was annexed by the U.S. in 1845, the Alamo’s surviving structure was eventually given a roof (the gable was added in 1850), and it functioned as a storage depot and commissary. A daguerreotype from 1849 shows the damage to the chapel’s façade before the gable was added. After the Catholic Church sold the building in 1883, there were plans to transform it into a hotel.

It was not yet the shrine it would come to be in the following century.

Now with the façade restored and the addition of the gable. Alamo buildings in use as Army supply depot, c. 1850–1870 (The San Antonio Light Collection, UT Institute of Texan Cultures)

Restoring the Alamo

Restoration of the Alamo started at the end of the nineteenth century when the Daughters of the Republic of Texas (DRT) took over the care of the building (after controversial discussions regarding responsibility for its caretaking). What people see today is the result of restorations that began in 1915.

Much of what had been added after 1836 was removed, once again altering the site’s appearance and how people understood it. Newly created buildings would also participate in memorializing and historicizing the Alamo. The gift shop was built to look as if it were constructed centuries earlier, but in reality was made in 1937 as a Centennial Museum to honor the hundredth anniversary of Texas independence. It displayed artifacts until the DRT transformed it into a store to sell souvenirs. The Arcade was built in the 1930s as a WPA project to beautify the site and help people find work during the Great Depression. This simulated historical “authenticity” aids in the performance of the primary narrative—the battle of 1836—not the Spanish mission.

The arcades

Even the way that visitors engage with the space has dramatically changed, attesting to the importance of understanding both the site’s physical location and historical context. Where once a large mission structure stood, visitors now only see a remnant that occupies only one-third the original footprint. The Alamo sits in the middle of downtown San Antonio, below towering skyscrapers. The juxtaposition is jarring, although you’d be hard pressed to find commercial images that show the building in its present urban context.

The cultural memories of the mission/the Alamo

Picture depicting he Alamo as a stylish promenade ground. Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, 1854 (DRT Library at the Alamo, San Antonio, TX)

Drawings, prints, paintings, and photographs have participated in creating this cultural memory of the Alamo. Drawings and prints in the mid-nineteenth century use the ruined space as a backdrop for elites in their fine clothing and carriages, in line with other artistic and literary movements that glorified the ruin. History paintings depict the Battle of the Alamo, with the chapel serving as its own character within the story instead of a mere backdrop.

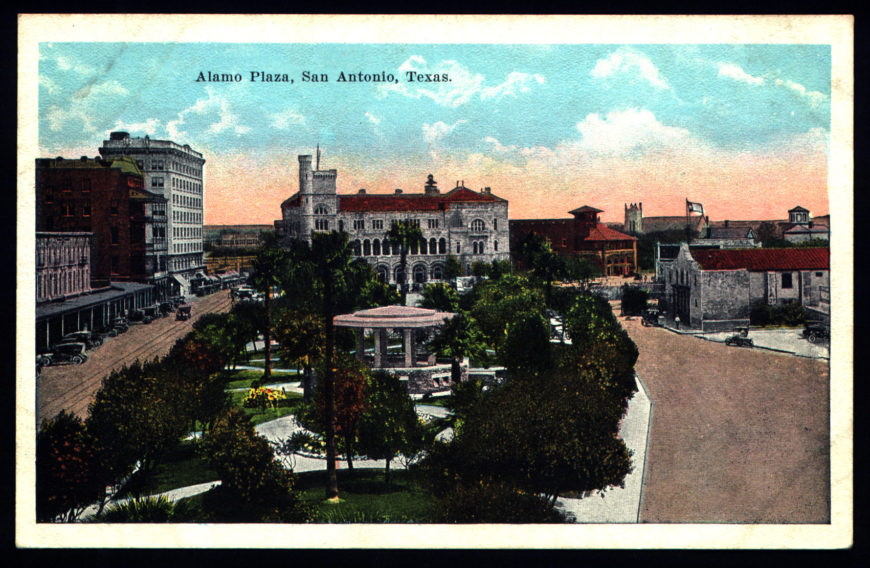

Early twentieth-century postcards often isolate the chapel, with little sense of the city around it gone. The longer history of the space as a mission is often obscured too. In the later twentieth and now in the twenty-first century, Latinx (including Chicanx) artists offer a new lens through which to remember the Alamo, with recent exhibitions such as “The Other Side of the Alamo: Art Against the Myth” in 2018. From César Martínez’s black and white photographs to Daniela Riojas’s digital photographic images, these artists draw attention to the ways this cultural icon signifies painful injustices and racial disparities. They are pushing back against the myth.

The complicated history of this place, a mission, ruin, battleground, emblem of patriotism, symbol of racial disparity, and tourist destination, has added yet one more layer to its story: in 2015, the Alamo became a UNESCO World Heritage Site as part of the San Antonio missions.

Notes:

[1] Donald Langmead, Icons of American Architecture: From the Alamo to the World Trade Center (Greenwood Press, 2009), p. 3

Additional resources

Holly Beachley Brear, Inherit the Alamo: Myth and Ritual at an American Shrine (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010)

James Early, Presidio, mission, and pueblo: Spanish architecture and urbanism in the United States (Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, 2004)

Richard R. Flores, Remembering the Alamo: Memory, Modernity, and the Master Symbol (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2002)

Gloria Fraser Giffords, Sanctuaries of earth, stone, and light: the churches of northern New Spain, 1530–1821 (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2007)

Todd Hansen, , ed. The Alamo Reader: A Study in History (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2003)

Peña, Daniel. “Remember the Alamo (Differently),” Texas Observer (22 Aug 2017)

Jacinto Quirarte, The Art and Architecture of the Texas Missions (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2002)

Ramos, Raul. “The Alamo is a rupture,” Guernica, 19 Feb 2019

Susan Prendergast Schoelwer, Alamo Images: Changing Perceptions of a Texas Experience (Dallas: DeGolyer Library, 1985)

Susan Prendergast Schoelwer, “The Artist’s Alamo: A Reappraisal of Pictorial Evidence, 1836–1850,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly, vol. 91 (April 1988)

Alexandra Minna Stern, “On the Road with Chicana/o History: From Aztlan to the Alamo and Back,” Pacific Historical Review 82, no. 4 (2013), pp. 581–587

Tomas Ybarra-Frausto, “Imagining a more expansive narrative of American Art.” American Art 19, no. 3 (Fall 2015), pp. 9–15