From a live webinar with Dr. Beth Harris. Discussion of copyright, public domain, fair use, and licenses until 16:00.

Disclaimer: We are not lawyers and Smarthistory does not offer legal advice about image use.

Jump to

- How does copyright and public domain apply to works of art?

- Museum overreach and the chilling effect

- Fair use of copyrighted material for teaching and learning

- Licenses for non-commercial use (Creative Commons)

- How to quickly find images that allow for non-commercial use

How does copyright and public domain apply to works of art?

Most basically, copyright lasts for a limited time, and then works enter the public domain, where they are free for use by all. (CAA)

The use of copyrighted works requires permission from the copyright holder except in the case of fair use or if the work has a license that allows use (such as a Creative Commons license).

Note: many publishers require explicit permission from museums or commercial agents (ARS and VAGA) even though these permissions may not be legally required.

In general, there are two levels of copyright to consider:

- The copyright that applies to the work of art

- The copyright that applies to the reproduction (usually a photograph) of the work of art

Copyright that applies to the work of art itself

First, you should find out if the work itself is in the public domain. Though there are some important exceptions to works of art published more than 96 years ago, in general you can follow these guidelines:

If the work was created 95+ years ago, it is likely now in the public domain in the U.S. (This does not necessarily apply worldwide.) This means that all creative work that was initially published or released before January 1, 1927 has entered the public domain and has no copyright protection as of January 1, 2022.

If the work was created less than 95 years ago, you will need to assess what type of image rights apply to the work itself. This varies. You can usually find this information on the webpage of the institution that owns the work.

Copyright that applies to the reproduction of the work of art

Here, you will need to consider whether the work pictured is two-dimensional (a drawing, painting, print, photograph, etc.) or three-dimensional (a sculpture, monument, building, etc.). Different legal standards apply to reproductions of two- and three-dimensional works.

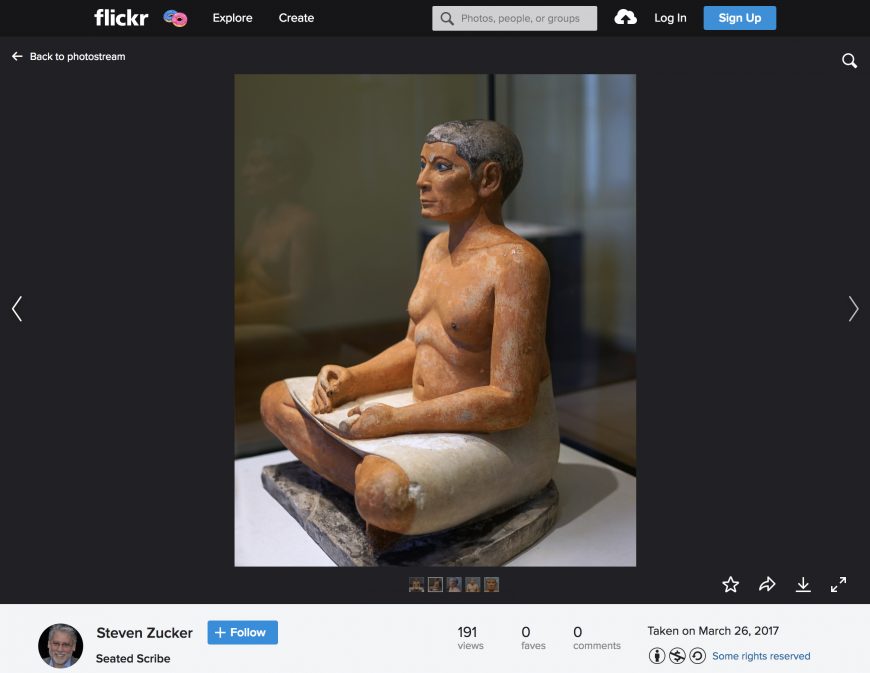

Although the Seated Scribe is out of copyright, many images of it are still copyrighted. This photo from Steven Zucker’s Flickr account is listed “Some rights reserved” and carries a Creative Commons license (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) that allows for it to be used for non-commercial purposes as long as it is attributed and shared with the same license. (Seated Scribe, c. 2500 B.C.E., c. 4th Dynasty, Old Kingdom, painted limestone, 53.7 x 44 x 35 cm, The Louvre, photo by Dr. Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

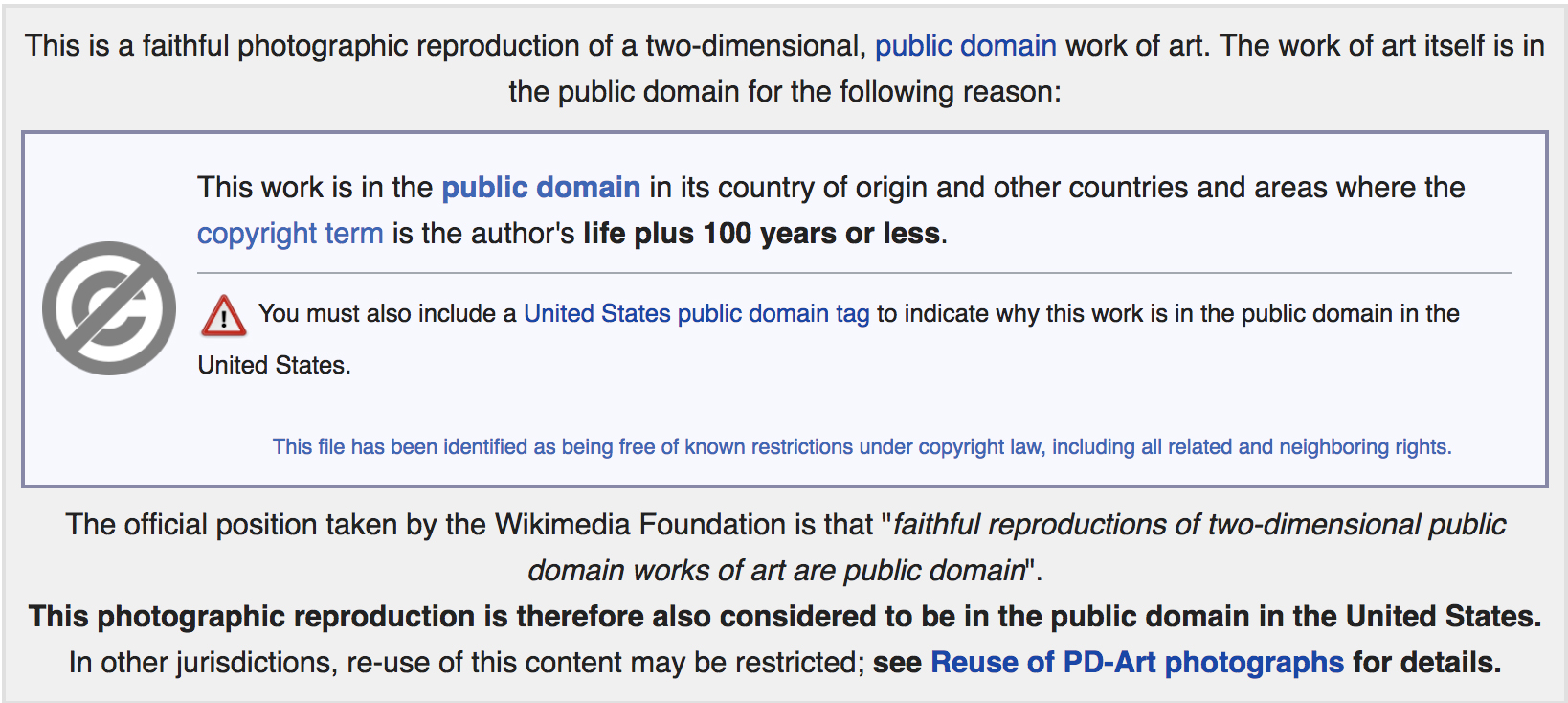

Photographs of two-dimensional works of art in the public domain are generally free to use. Thanks to the decision in the Bridgeman case (widely accepted though not law), a photograph that is a faithful reproduction of a two-dimensional work in the public domain cannot be copyrighted (though copyright is often asserted by museums and other institutions). This is called copyright overreach. In other words, copyright requires novel invention, which is not the case with a faithful reproduction.

Photographs of three-dimensional works of art, no matter whether the work depicted is in the public domain or not, can be copyrighted. To find an image you can use without securing copyright permission, you will need to search for an image that is public domain or licensed for reuse. You can search in Creative Commons, in Google images (using “tools”), or you can use an advanced search in Flickr (see below for more on this).

Museum overreach and the chilling effect

Sometimes museums claim copyright on photographs of works of art that are in the public domain (this is referred to by some as “overreach“). When institutions attach copyright notices to public domain works, the legal language, even if unenforceable in court, chills the public’s use of these scans for far-ranging educational, artistic, and commercial purposes. (Pittman)

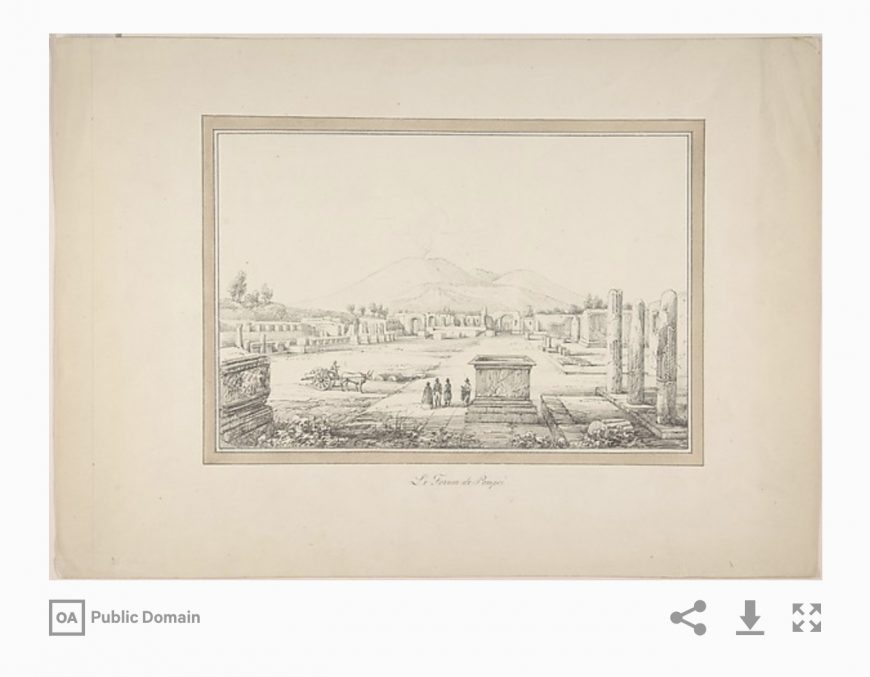

This 19th-century print from The Metropolitan Museum of Art is clearly labeled on their website as “public domain,” and they provide a link to download a high-resolution version of the image. (View of Pompeii, 19th century, pen and black and gray ink, 25.7 x 34.5 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Fair use of copyrighted material for teaching and learning

Here’s what the CAA guidelines say about fair use of copyrighted material for teaching and learning:

The right to make fair use of copyrighted materials is a key tool for the visual arts community, although its members may not always choose to take advantage of it. They may still seek copyright permissions, for instance, to maintain relationships, to reward someone deemed deserving, or to obtain access to material needed for their purposes. But, in certain other cases they may choose instead to employ fair use of copyrighted material in order to accomplish their professional goals. (CAA)

Copyright protects artworks of all kinds, audiovisual materials, photographs, and texts (among other things) against unauthorized use by others, but it is subject to a number of exceptions designed to assure space for future creativity. Of these, fair use is the most important and the most flexible. (CAA)

Teachers in the visual arts may invoke fair use in using copyrighted works of various kinds to support formal instruction in a range of settings, as well as for uses that extend such teaching and for reference collections that support it, subject to certain limitations. (CAA)

See the CAA guidelines here for specific examples of those limitations (teaching and writing).

Licenses for non-commercial use (including Creative Commons)

Museums are increasingly including image rights directly on the webpages where works are displayed. If the page you are looking at does not include this information, refer to the general guidelines available on the institution’s website (usually under “Rights and Reproductions”).

A Flickr license as it appears on the photo page. The icons shown correspond to aspects of the CC license (BY-NC-SA in this case). Clicking on “Some rights reserved” brings you to the corresponding CC license page with a full explanation.

On sites such as Wikimedia Commons and Flickr, licenses are clearly displayed at the bottom of the page. These generally follow the Creative Commons (or CC) licensing format. However, it is very important to understand that images published online may not be labeled with an accurate license.

There are several components to CC licenses:

- BY: short for “byline,” meaning you must credit the author of the image

- NC: “non-commercial,” meaning that the image can’t be used for commercial purposes

- SA: “share alike,” meaning you need to openly license the work you create using the image in question in the same way that the image itself is licensed

- ND: “no derivatives,” meaning the image can’t be edited (color changed, cropped)

- 2.0, 3.0, etc.: usually the license is followed by a version number, referring to the version of Creative Commons licensing under which it was released

Tip: When using a CC-licensed image, it is common practice to display the license alongside the credit. It is also nice to provide a link to the original image source. For example:

| Caravaggio, The Calling of St. Matthew, c. 1599-1600, oil on canvas, (Contarelli Chapel, San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome) photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 <https://flic.kr/p/FV2RkF> |

How do I quickly find images that allow for non-commercial use?

Note: These tools are useful, but keep in mind that sometimes people put a restrictive license on something in the public domain, or they put an open license on images they have no right to—so reading through the guidelines linked above will help you make good decisions.

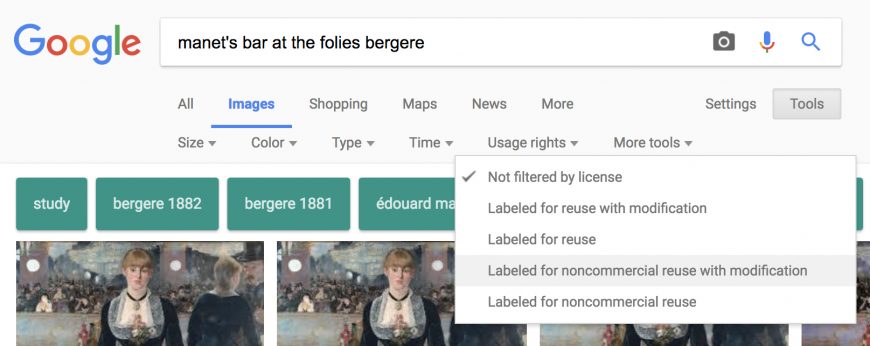

When searching in Google Images, you can select “Tools” on the right-hand side of the menu, then select an option that fits your needs from the “Usage rights” menu.

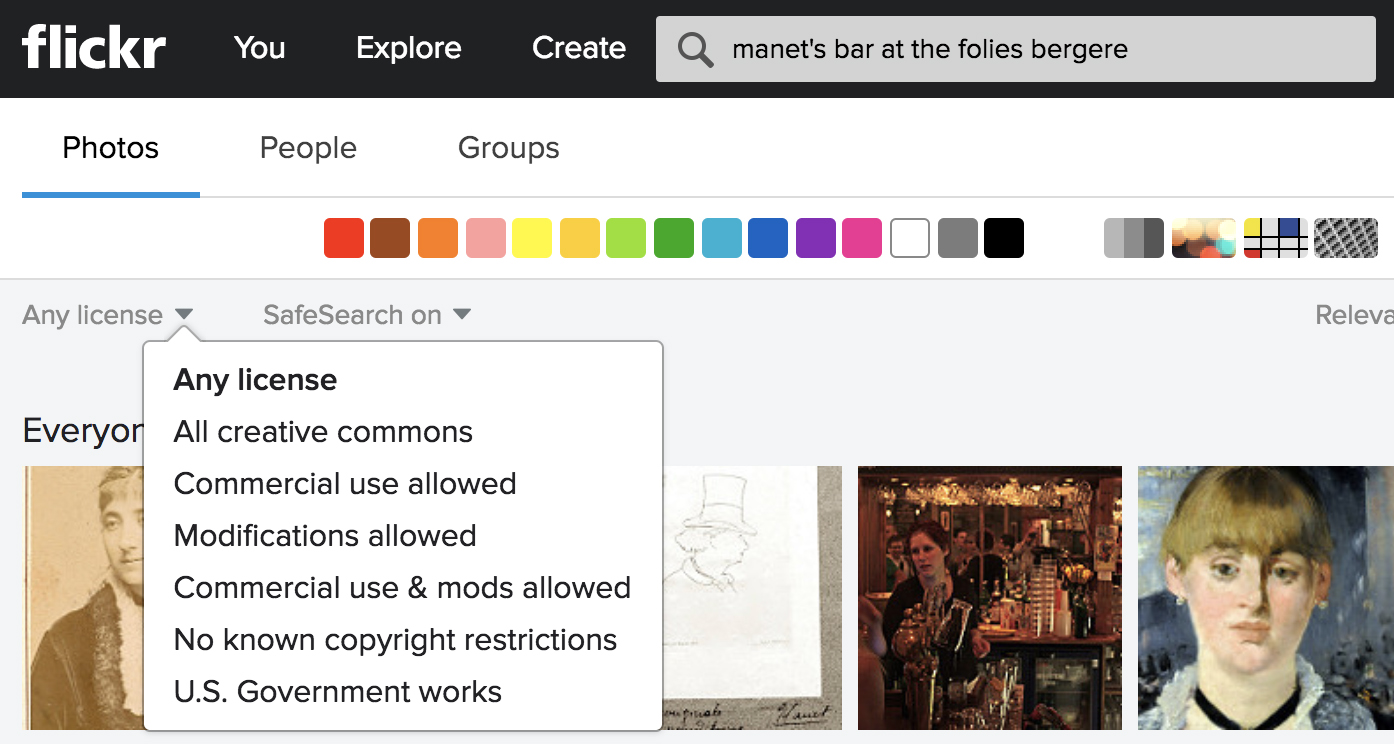

On Flickr, select the licensing drop-down menu at the far left, and choose the option that fits your needs. The license for any Flickr image is displayed at the bottom of the page on the right. Clicking on the license icons will display the full license on the Creative Commons webpage.

For an image on Wikimedia Commons, you can find the license displayed below the image and author information on its file page.

How do I cite image sources?

Here is how we do it at Smarthistory:

For a work in the public domain:

Plate with a king hunting rams, Sasanian Iran, 5th–6th century C.E., silver with mercury gilding and niello inlay; 21.9 cm diameter (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

For a CC-licensed work:

Augustus of Primaporta, 1st century C.E., marble, 2.03 meters high (Vatican Museums) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

For a work in copyright:

Kiki Smith, Lying with the Wolf, 2001, ink and pencil on paper 88 x 73″ (Centre Pompidou, Paris) © Kiki Smith

Learn more about searching for high-quality images next.

Additional resources:

Chart outlining different levels of copyright and public domain per U.S. law.

Kenneth D. Crews, “Museum Policies and Art Images: Conflicting Objectives and Copyright Overreaching” (July 1, 2012), Fordham Intellectual Property, Media & Entertainment Law Journal, Vol. 22, p. 795, 2012.

“Museum Image Fees: A call to Arms” by Bendor Grosvenor

The College Art Association’s Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts