1980s New York was tragic, gritty, and electrified by artists who brought their art into the street.

1980–today

1980s New York was tragic, gritty, and electrified by artists who brought their art into the street.

1980–today

Osorio’s art explores the experience of being Puerto Rican in New York City.

Art historian Gregory Salter considers Freud’s paintings of queer and marginalized bodies in the age of Section 28, the early years of HIV/AIDS, and preoccupations about class and gender.

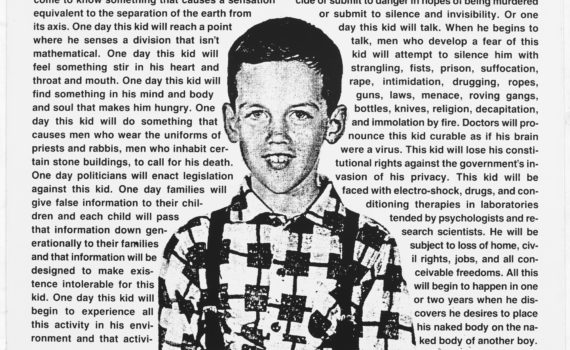

Having the young Wojnarowicz’s face disseminated as a visible queer child was a potent political symbol.

Pepón Osorio's installation illuminates the experience of a father and son separated by incarceration.

Teraoka draws on Japan's brilliant history of art and kabuki theatre to creating beauty from heart-rending tragedy.

Haring’s subway drawings were born from his desire to create art that was accessible for everyone.

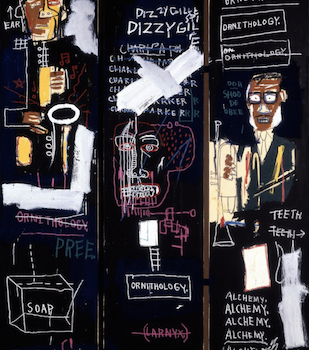

Basquiat appropriated wildly—and creatively—from Old Masters, Picasso, anatomical textbooks, and even jazz.

Gonzalez-Torres evokes absent bodies in his works, which bring gay identity and the AIDS crisis into public view.