For much of the Middle Ages dead cows were the main ingredient for books. What was frolicking in the meadow one month, may have been a page in a Bible the next.

c. 330–1300 C.E.

For much of the Middle Ages dead cows were the main ingredient for books. What was frolicking in the meadow one month, may have been a page in a Bible the next.

c. 330–1300 C.E.

We're adding new content all the time!

Dr. Ilana Tahan explores the illumination of Jewish biblical manuscripts, looking at the religious grounds for artistic expression in the Bible, and the differences in styles between manuscripts produced in the Near East and those in Europe

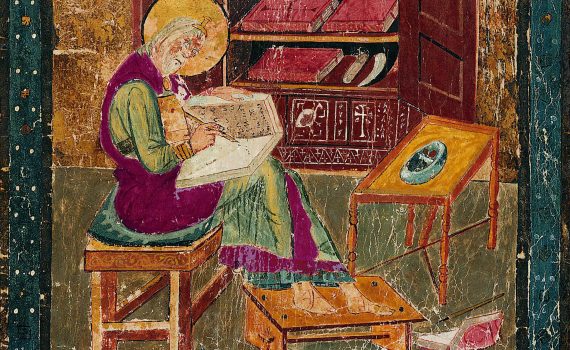

Dr. Kathleen Doyle introduces the characteristics and evolution of medieval biblical illumination, discussing the various functions of images in biblical texts, together with the use of different materials, calligraphic embellishments and stylistic influences.

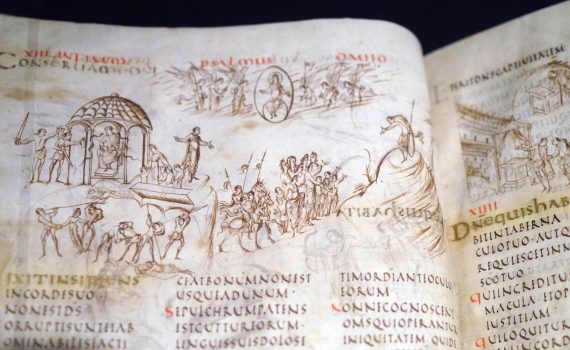

Expressive, emotional, and energetic, the Utrecht Psalter is not what you expect in a book written 1200 years ago.

One of the oldest surviving bibles was made in England but has clear visual ties to traditions from the ancient Mediterranean.

From scraping skin and cutting quills to painting and bookbinding, making a manuscript is a long, complex process.

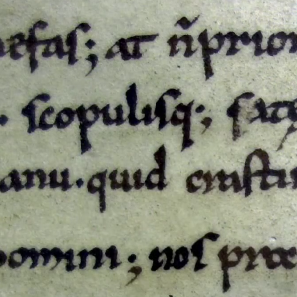

Angular or rounded? Medieval script reveals not only what the author wrote, but when and where the book was made.

Go on, judge a book by its sound. The thinner the parchment, the higher the pitch—and the price.

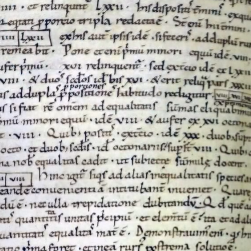

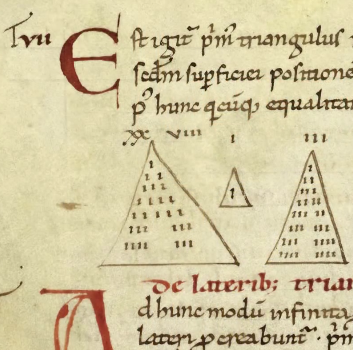

This 1000-year-old math primer is nothing fancy, but it took months for a scribe to make.

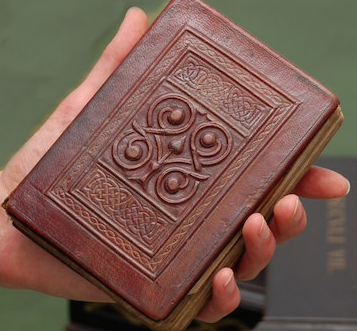

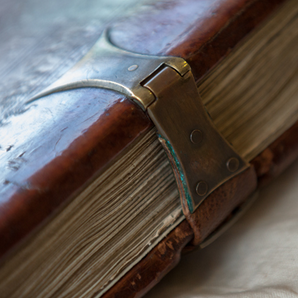

Animal skin lent a durable writing surface to medieval scribes. When tanned and tooled, it also protected books.

Is that a body, or a book? Arms, hands, feet, skulls—all can feature in the anatomy of a medieval manuscript.

Medieval libraries hid a forest in their shelves—wood boards, covered and clasped, protected precious parchment.