Using a varied collection of Hebrew manuscripts, Dr Ilana Tahan explores the illumination of Jewish biblical manuscripts, looking at the religious grounds for artistic expression in the Bible, and the differences in styles between manuscripts produced in the Near East and those in Europe.

Books have historically been cherished possessions in Judaism and as such adorned and beautified with decorations and pictures. Increasing their visual appeal would also have enhanced their value to their owners, especially if they were made of parchment and were written by professional scribes.

The majority of extant Hebrew manuscripts are from the medieval period. Commissioned and owned by affluent patrons, medieval Hebrew illuminated manuscripts were considered important status symbols and art objects in their own right. Proudly displayed and carefully looked after, these splendid books were parted with only in times of hardship.

Does Judaism allow images in its sacred texts?

The inclusion of imagery in Hebrew manuscripts begs two fundamental questions. First, can figurative painting be reconciled with the injunction in the second biblical commandment, which explicitly forbids it?

Thou shalt not make unto thee a graven image nor any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth; thou shalt not bow down thyself unto them, nor serve them. (Exodus 20. 4–5)

With regard to sacred texts a strict ban on any decoration still applies to the copying of a Torah scroll. But further to these, the answer lies in the biblical passage itself: imagery is not permissible if used in idol worshipping. Accordingly, not all forms of artistic expression are forbidden in Jewish law. In general, rabbinic authorities permitted, albeit reluctantly, two-dimensional figurative representations, but three-dimensional objects, such as sculptures, were strictly prohibited.

As to the second question – is Judaism congenial to art? – it has been a long-held view that Jews considered art, especially figurative art, objectionable, but this seems to be unfounded. Indeed, as far back as biblical times it appears that artistic endeavour was, in fact, much appreciated. The biblical text in which God instructs Moses how to adorn and decorate the holy Tabernacle and its furnishings, is definitely a case in point (Exodus 25).

Over time, but especially in the medieval period, rabbis and sages who may have been initially averse to artistic forms began to see art as a means of enriching spirituality rather than an impediment to it. They interpreted the verse ‘This is my God and I will praise Him; my father’s God and I will exalt Him’ (Exodus 15. 2) as an exhortation to glorify the Lord through visual splendour. Thus, the concept of hidur mitsvah (beautification of the commandment) became the underlying justification for adorning and embellishing ceremonial artefacts, manuscripts of sacred and religious texts and other objects employed in Jewish rituals. Worshipping and venerating the Creator through visual beauty would bring one closer to His divine mercy and His commandments. In his Sefer Ma‘aseh Efod (‘The Story of Efodi’) the Spanish-Jewish philosopher Profiat Duran (d. 1414) explains how art can inspire and stimulate holiness and learning:

Study should always be in beautiful books, pleasant for their beauty and the splendour of their scripts and parchments, with elegant ornament and covers … It is also obligatory and appropriate to enhance the books of God and to direct oneself to their beauty, splendour and loveliness. Just as God wished to adorn the place of His Sanctuary with gold, silver and precious stones, so is this appropriate for His holy books, especially for the book that is ‘His Sanctuary’.

During the Middle Ages the art of the book became the centre of all artistic creativity for Jewish communities in the Near East and Europe. Adorning and decorating their Bibles, liturgies and legal codes became one of the most meaningful ways in which to express their belief in the Creator and the written word. Living in a medieval non-Jewish environment, Jewish scribes and artists were often influenced by the contemporary artistic trends of the countries in which they lived. Consequently, two important traditions of Hebrew illuminated manuscripts can be distinguished – one showing the influence of the Muslim artistic style prevailing in the Near East, and the other revealing a close affinity with the styles of illumination in Christian Europe.

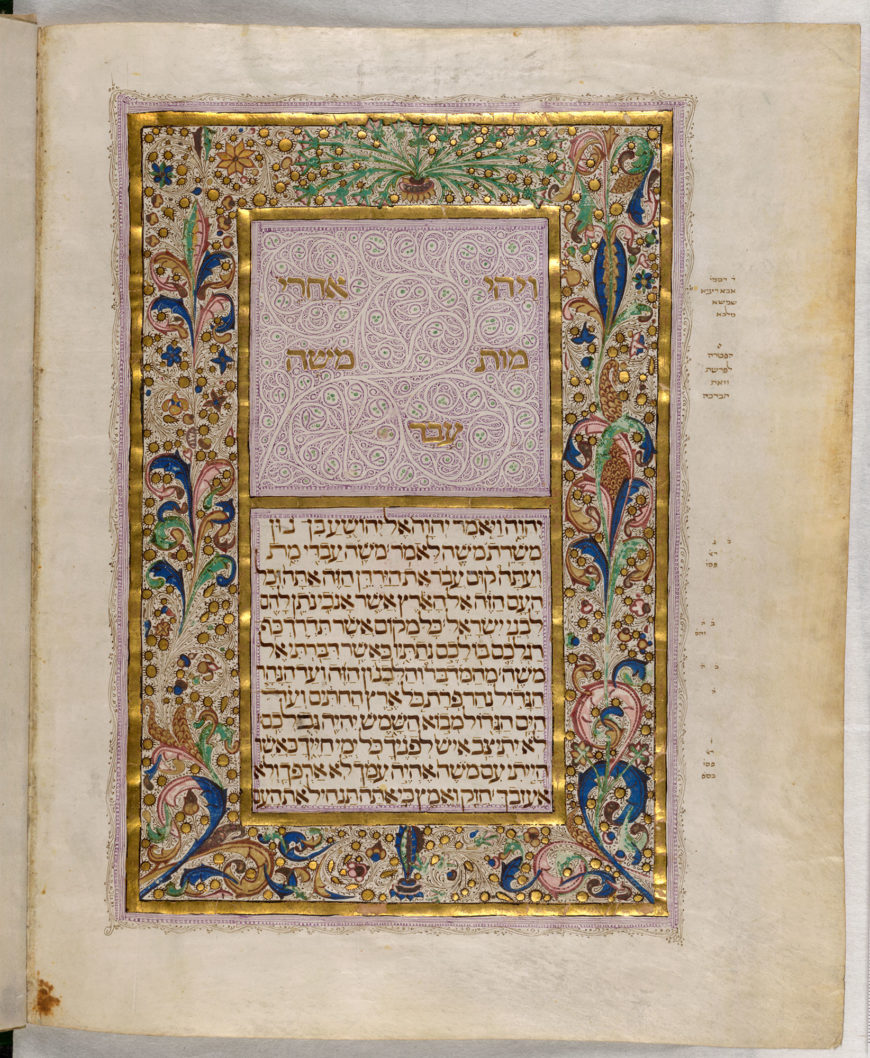

The Lisbon Bible is the most accomplished dated codex of the Portuguese school of medieval Hebrew illumination. Its three volumes comprise all twenty-four books of the Hebrew Bible. Completed in 1482, the Lisbon Bible is a testimony to the rich cultural life the Portuguese Jews experienced prior to the expulsion and forced conversions of 1496. Shemu’el ben Shemu’el ibn Musa (scribe), The Lisbon Bible, 1483, parchment, 21 x 14 cm (The British Library)

Artists, scribes and scripts

Although a Jewish scribe had the crucial role of overseeing the execution of the entire manuscript, unless he was also an artist he would normally have entrusted the decorations to professional illuminators. In some medieval Hebrew manuscripts the illuminations were in fact executed by non-Jewish artisans, which clearly testifies to cross-cultural ties between Jewish scribes and Christian illuminators.

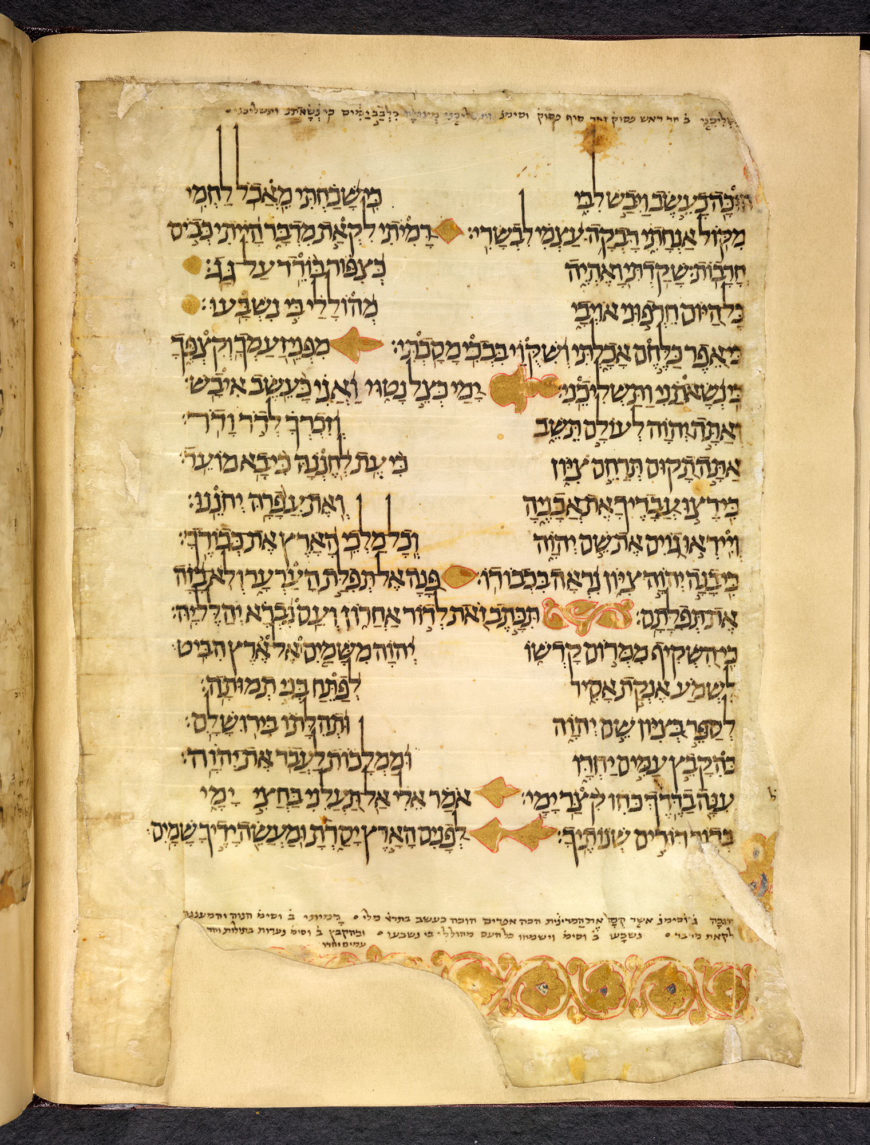

In Hebrew manuscript ornamentation the script itself is undoubtedly the most significant component. At every step Jewish scribes emphasise the power of words through the letters of the Hebrew alphabet. Jewish copyists strove to enhance the beauty of the Hebrew script through a diversity of techniques: one cannot but marvel at the perfect evenness of Sephardi letters in the Spanish King’s Bible, and the beautifully tapered Ashkenazi characters of the Duke of Sussex’s German Pentateuch.

![Ya῾aḳov ben Yosef of Ripoll [scribe], Bible (the 'King's Bible'), with vowel-points and accents, 1384–85, parchment, 33.5 x 27 cm (The British Library)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Kings-Bible-Kings_MS_1_f031r-870x1155.jpeg)

A 14th-century Hebrew Bible, produced in Solsona, Catalonia, northeast Spain. Ya῾aḳov ben Yosef of Ripoll [scribe], Bible (the ‘King’s Bible’), with vowel-points and accents, 1384–85, parchment, 33.5 x 27 cm (The British Library)

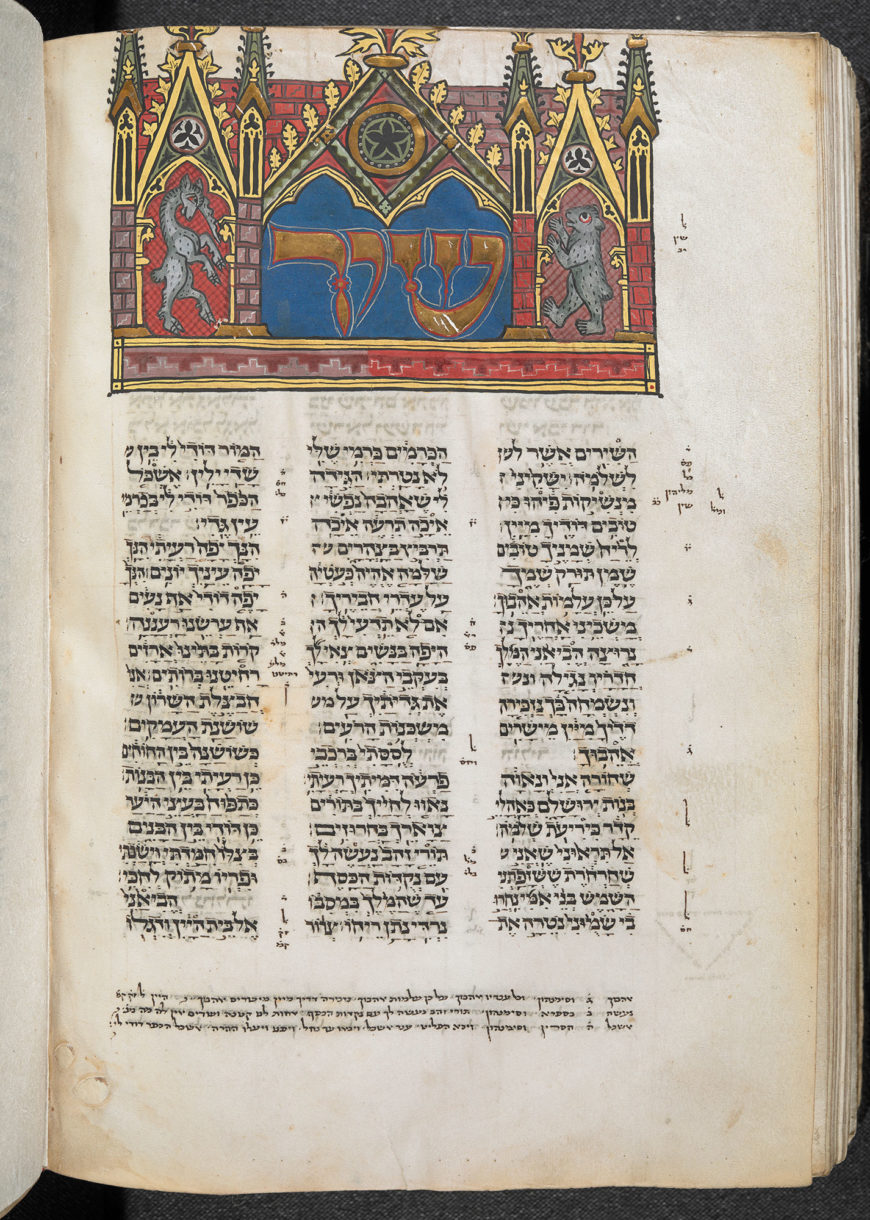

The Duke of Sussex’s German Pentateuch is a fine example of the South German style of illumination. Hayyim, Torah: Pentateuch (aka the ‘Duke of Sussex’s German Pentateuch’), 1300–1324, parchment, 23 x 16 cm (The British Library)

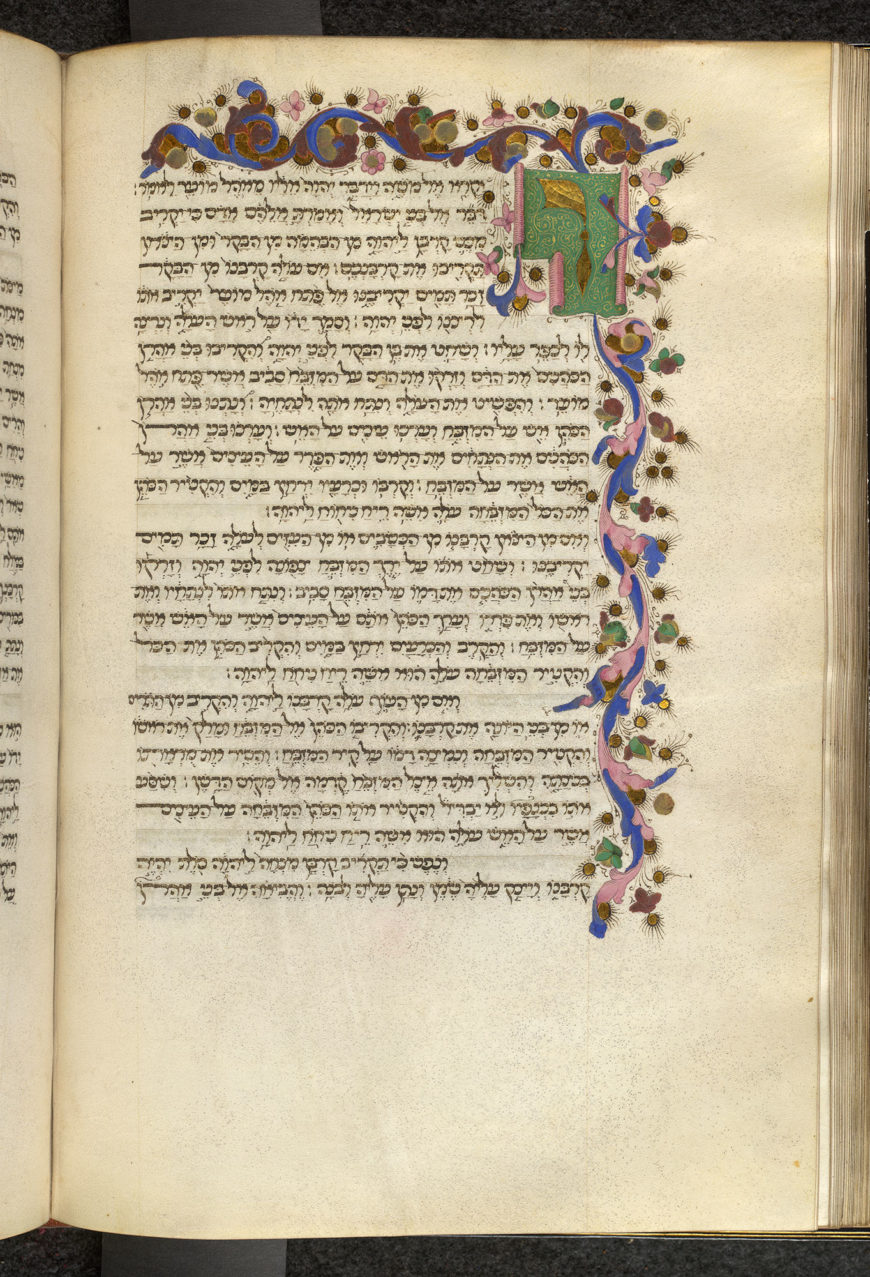

Visual impact also comes from the decorations that invariably grace the incipits (opening pages) of many a Hebrew manuscript. Since the Hebrew alphabet lacks upper-case characters, Jewish scribes customarily decorated the first words of text rather than individual letters. Only seldom, in an attempt to emulate practices employed by their Christian counterparts, did Jewish scribes embellish first letters.

A 15th-century Pentateuch featuring illuminated letters, which are rare in Hebrew manuscripts. Yitsḥaḳ ben ῾Ovadyah ben Daṿid of Forli (Gaio di Servadio), Pentateuch, c. 1441–1467, parchment, 22 x 22.5 cm (The British Library)

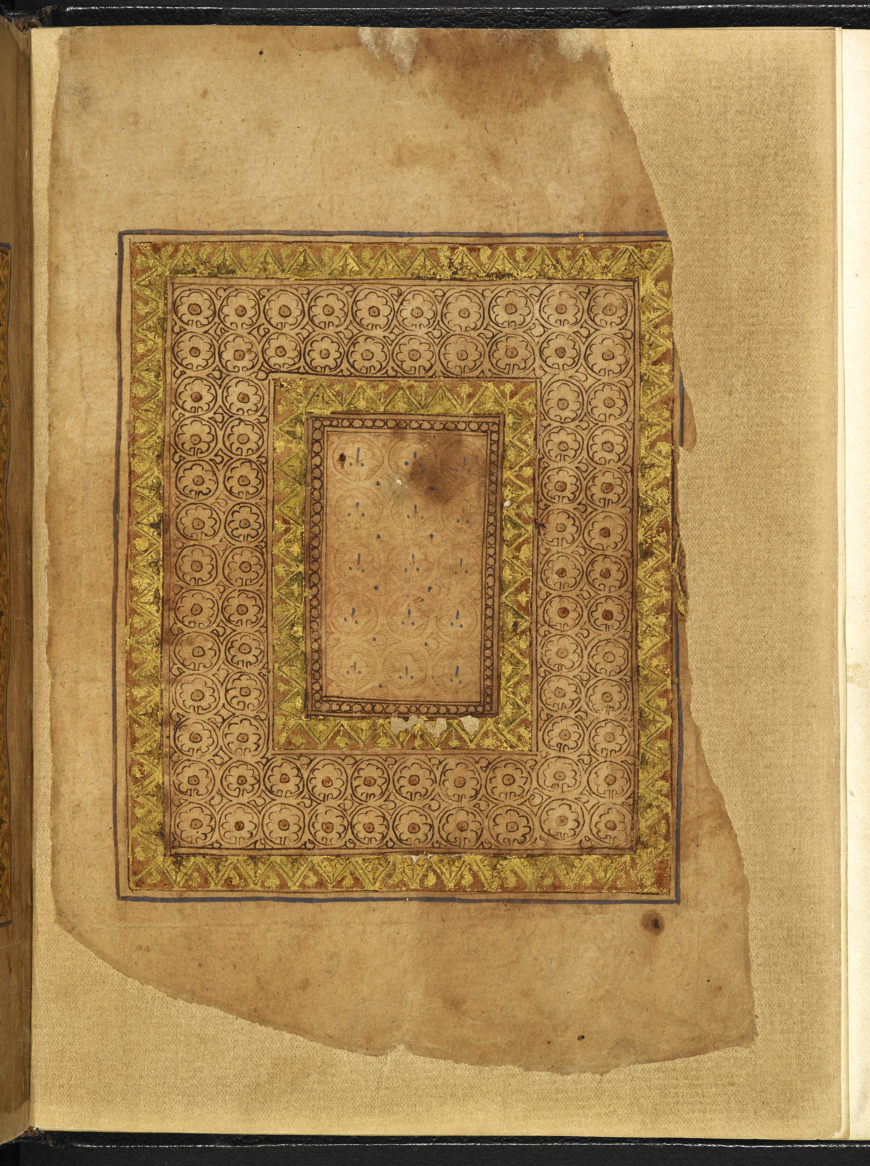

Islamic abstract influence

The earliest decorated Hebrew manuscripts were produced between the 9th and 12th centuries in the Islamic Near East, mainly in Egypt and Palestine. These were largely biblical codices, which shared many artistic and stylistic features with contemporary Qur’ans. Owing to these marked ornamental similarities, it has been suggested that these Bibles may have been written for the Karaites, a Jewish sect founded in the 8th century CE, who nurtured a close kinship to Muslim culture. For an example of this, see the striking Karaite Exodus with Islamic-style carpet pages and Hebrew text transcribed in Arabic characters.

Islam’s symbolic approach had a profound and lasting impact on Hebrew manuscripts created in Muslim lands. Like Qur’ans, early Hebrew Bibles are entirely devoid of human and animal imagery, and their ornamentation is overtly functional. Elements emphasised in Qur’anic art are adapted to the Jewish manuscript context, as illustrated, for instance, in the First Gaster Bible.

Karaite Book of Exodus: Fragments from Exodus, estimated 10th century C.E., 9 x 7 inches (The British Library)

Islam’s symbolic approach had a profound and lasting impact on Hebrew manuscripts created in Muslim lands. Like Qur’ans, early Hebrew Bibles are entirely devoid of human and animal imagery, and their ornamentation is overtly functional. Elements emphasised in Qur’anic art are adapted to the Jewish manuscript context, as illustrated, for instance, in the First Gaster Bible.

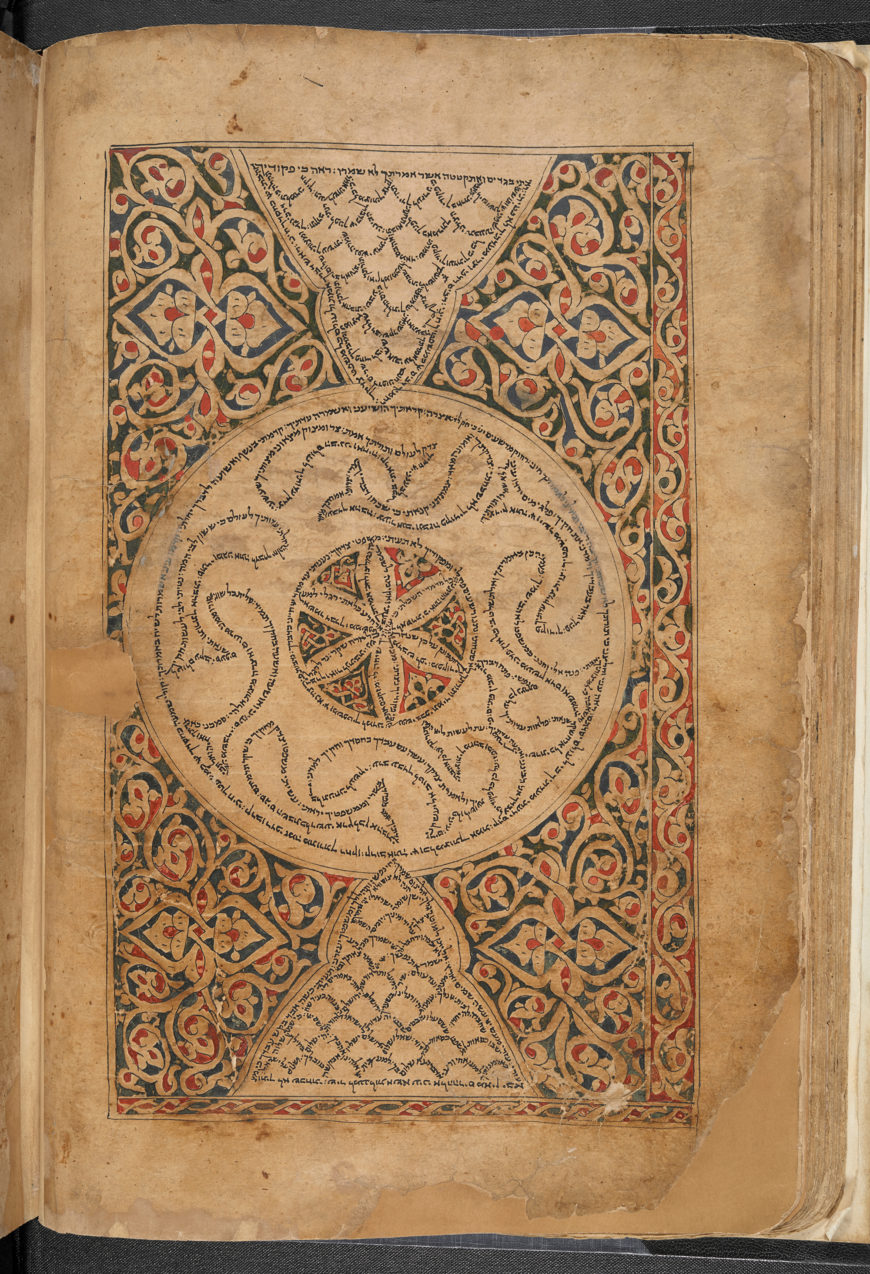

The First Gaster Bible is also a very good example of manuscript illumination from the Islamic East. It contains an abundance of gold embellishments executed in Islamic style. Biblical fragments (‘First Gaster Bible’) with masorah magna and parva, 10th century, parchment, 33 x 26 cm (The British Library)

During the 14th century an important school of Hebrew manuscript painting developed in Yemen, reaching its pinnacle in the second half of the 15th century. Surviving manuscripts from the latter period, such as the famous Sana’a Pentateuch, present a skillful blend of Jewish artistic elements and adapted Islamic motifs. In particular, this manuscript incorporates micrography, which is the weaving of minuscule lettering into abstract, geometric and figurative designs, in this case a fish design.

The San’a Pentateuch is famed for its superb carpet pages, with stylised representations of mountains and fish swimming in the sea, outlined in scriptural micrography. The text used to create the micrographic shapes was taken from the Book of Psalms. The San’a Pentateuch, 1469, parchment, 40 x 28 cm (The British Library)

Unique to Jewish art, this scribal practice started around the 9th century in Egypt and Palestine, before it gradually spread to Europe and Yemen; it still continues to this day. Initially, Jewish scribes employed text from the Masorah (body of rules on the reading, writing and intonation of the biblical text) to devise micrographic patterns, but over time they began relying on other sources, a particular favourite being the Book of Psalms. Although human depictions are banned and the decoration is rooted in functionality, the incorporation of micrographic patterns creating outlines represents a departure from the stern anti-figurative attitude.

Western Christian influence

In Western Christendom the illumination of Hebrew books began around the 13th century, continuing until the close of the 15th century. Throughout this period schools of Hebrew manuscript painting were established in Ashkenaz (the Hebrew name for an area that covers England, northern France and Germany), in Sepharad (Hebrew for Spain, also covering Portugal) and in Italy.

The Sephardi manuscript legacy mirrors the cross-cultural ties between Jews, Christians and Muslims in the centuries leading up to the Jewish expulsion from the region. Peculiar to the decoration of Spanish Hebrew Bibles is the absence of narrative elements and human imagery, and an apparent predilection for Islamic artistic forms. This is surprising as they mostly emanate from areas within Spain where Muslim dominance had ended long before. Some scholars maintain that the Islamic component in Spanish Bibles is an obvious expression of the prolonged Jewish-Arab cultural interaction in Muslim Spain, and of the eagerness among the Sephardi elite to keep alive the Judaeo-Islamic heritage. This coexistence, known as the Golden Age of Spanish Jewry, lasted over 400 hundred years (c. 8th to 12th century).

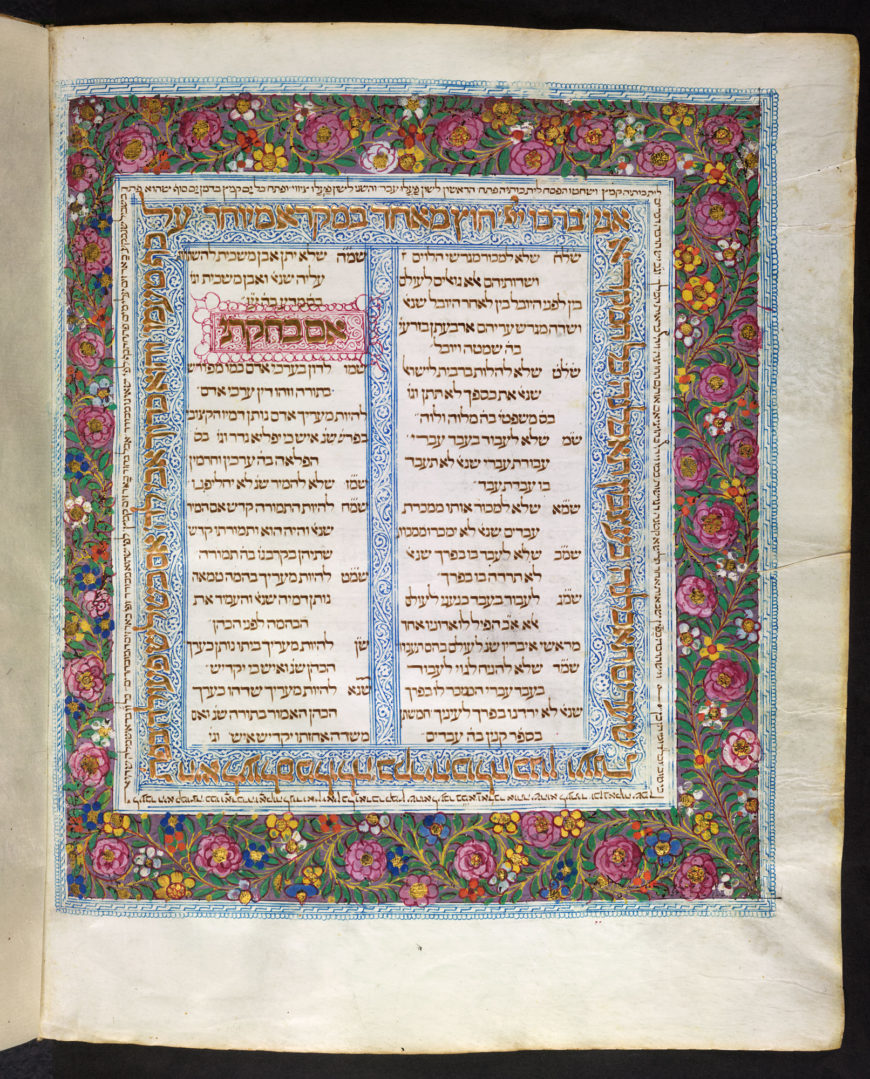

The complete absence of narrative illustrations in the Hebrew painted codices from Portugal is amply compensated for by their unrivalled opulence and refinement. Their displays of floral and faunal motifs, laced with intricate filigree pen work and burnished gold script, attests to the highest level of craftsmanship. The iconic Lisbon Bible is a perfect example of such artistry.

Shemu’el ben Shemu’el ibn Musa (scribe), The Lisbon Bible, 1483, parchment, 21 x 14 cm (The British Library)

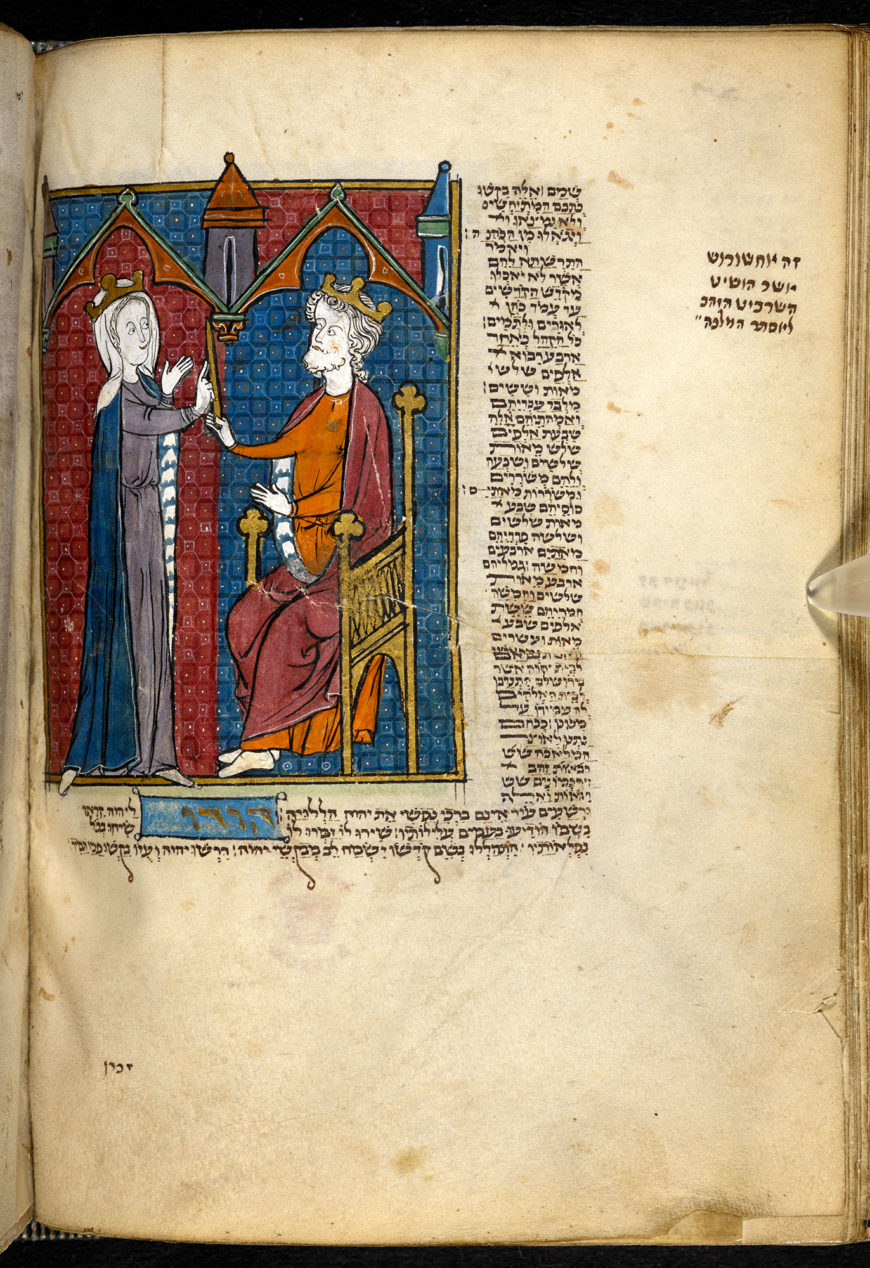

Hebrew painted manuscripts originating in France, Germany and Italy show great similarities in decoration to contemporary Christian manuscripts from the same region. Their style and methods of production were profoundly affected by the artistic currents in the host cultures. Thus manuscripts from Ashkenaz tend to follow the Gothic styles fashionable in France and Germany during the 13th and 14th centuries. Remarkable specimens include the exquisitely wrought North French Hebrew Miscellany, with numerous stunning biblical illustrations.

Full-page miniature of Ahasverus handing over the golden scepter to Esther in an architectural frame (Esther 8. 4). The caption reads: ‘This is Ahasverus held out the golden sceptre toward Esther, the queen‘. Isaac ben Joseph of Corbeil (author), Mosheh ben ‘Ezra (author), Eliyahu Menaḥem ha-Zaḳen (author), Binyamin (scribe), Miscellany of biblical and other texts (‘The Northern French Miscellany’), 1278–1324 C.E., parchment, 16 x 12 cm (The British Library)

Apart from exquisitely embellished Jewish biblical texts, the British Library’s uniquely varied collection of Hebrew manuscripts contains striking and beautifully illuminated examples of European medieval Passover liturgies, codes of law and philosophical works, as well as lavishly decorated and illustrated marriage contracts, Esther scrolls and liturgical texts that were produced in Europe, the Near East and Asia, between the 16th and 19th centuries.

Written by Ilana Antoinette Tahan

Ilana Antoinette Tahan, M.Phil., OBE has been educated at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, Israel, and at the Aston University, Birmingham, UK where she was awarded the Master of Philosophy degree. Ilana joined the British Library as Hebraica Curator in 1989. In 2002 she became Head of the Hebrew Section in charge of one of the finest Hebraic collections in the UK, comprising some 3,000 Hebrew manuscripts, ca. 7,000 Genizah manuscript fragments, and over 70,000 printed books. Since 2010 Ilana has been Lead Curator of Hebrew and Christian Orient Studies. In addition to being responsible for the significant British Library’s Hebraic collections, she also manages the Library’s Christian Orient collections which include the Armenian, Coptic, Ethiopian, Georgian and Syriac holdings. In 2009 Ilana was awarded the Order of the British Empire for services to scholarship. Some of Ilana’s important publications include: Hebrew manuscripts: the power of script and image, (London: the British Library, 2007) and Sacred: books of the Three Faiths Judaism, Christianity, Islam, edited by John Reeve … Catalogue contributions by : Colin F. Baker, Kathleen Doyle, Scot McKendrick, Vrej Nersessian, Ilana Tahan (London: the British Library, 2007).

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

Originally published by The British Library.