Illuminated manuscripts offer some of the best evidence for our understanding of Christian artistic interpretations of the Bible. Through them we can begin to appreciate the value placed on such art. Only significant investment of resources – hours of labour and significant expenditure – made such works possible. Each manuscript, by definition, was made by hand (Latin manu scriptus: ‘written by hand’), and each illumination required the dedicated work of a highly skilled person, or persons. Each incurred significant cost in materials and the time spent on its production. No wonder, then, that so many illuminated manuscripts of the Bible were treasured in their day for more than their material value, and gained the status of gifts worthy of saints and kings.

Decorative and illuminated calligraphy is present in the sacred texts of several religions, but among the Abrahamic faiths only Christian scripture is also illustrated extensively in grand copies. Within the Jewish tradition, figurative imagery is limited to certain books and biblical commentaries (never the Torah). This is based on a strict interpretation of the Second Commandment against graven images or likenesses (Exodus 20.4). However, in both Western and Eastern Christendom almost any type of decoration is possible, whether individual narrative images in letters, literal or allegorical illustration, or story-telling biblical picture books where text is minimal.

For over a thousand years, and throughout the Christian world, scribes and artists embellished and illustrated biblical manuscripts in order to adorn and elaborate the sacred text. The most sumptuous works that they produced are now described as ‘illuminated’, meaning that they are enhanced by the application of gold or silver and painted or drawn decoration. In the early medieval period, most scribes and illuminators were monks or clerics. In the later Middle Ages, these activities were taken over, generally, by commercial lay scribes and artists. Many artists worked collaboratively in loose associations or partnerships in major towns and cities such as London, Paris, Utrecht, Rome and Bruges. From documentary evidence it is clear that many of these artists worked in a variety of media, but it is almost exclusively their painting in books that survives and gives us a glimpse into the great artistry of the Middle Ages.

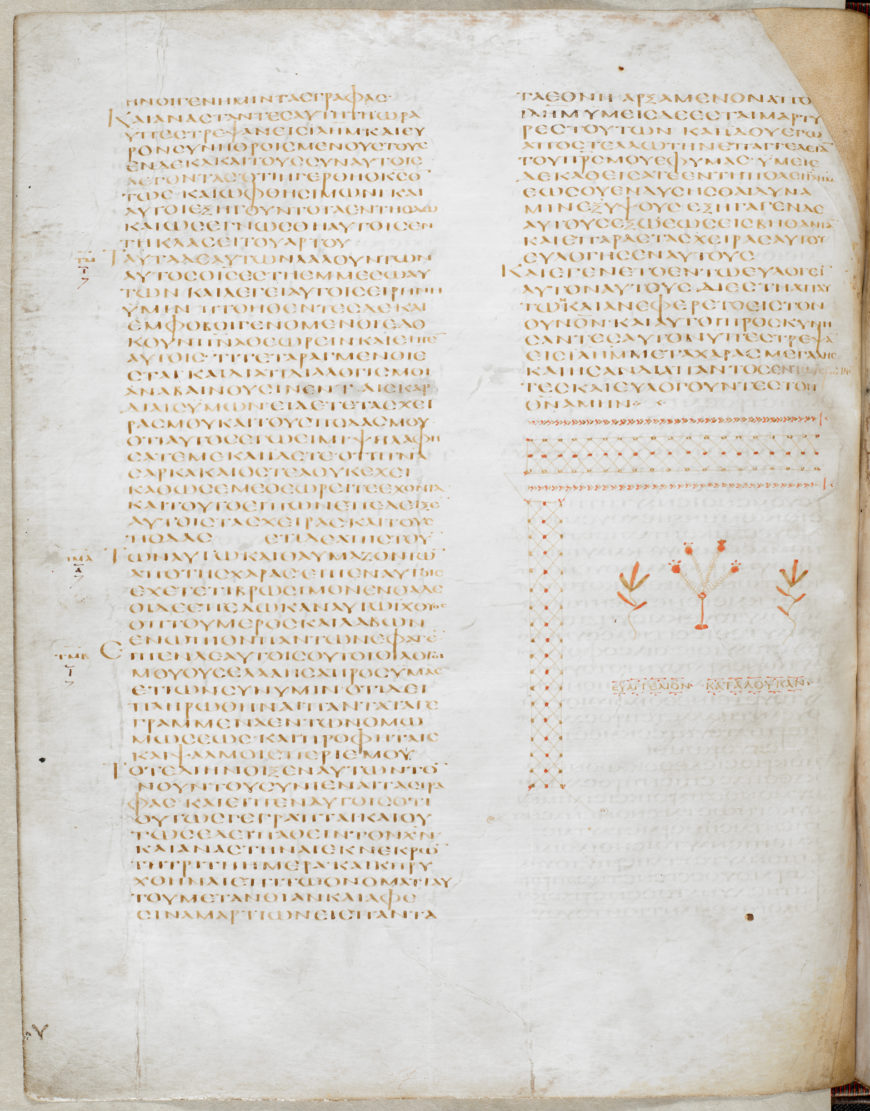

A decorative panel, or ‘endpiece’, following the Gospel of St Luke in the Codex Alexandrinus. Codex Alexandrinus (Gregory-Aland 02), Bible in four volumes: Volume 4 (New Testament), 5th century, parchment codex, 32 x 28 cm (The British Library)

The justification for the use of images

Illumination of Christian Bibles seems to have been taken place from an early date. The first decoration occurs in the earliest surviving complete copy of the entire canon: Codex Alexandrinus, dating from the 5th century. In this Greek Bible, the decorative panels at the end of each book (‘endpieces’) include stylised botanical images as well as other forms, such as a chalice, a Eucharistic symbol.

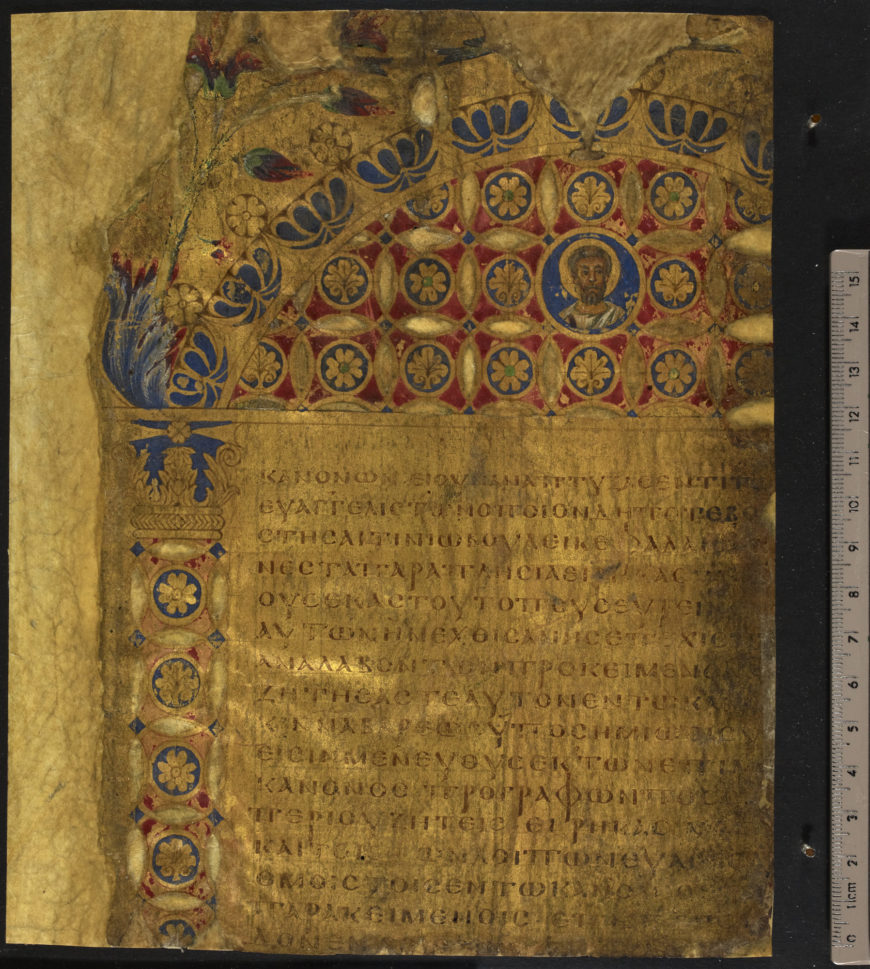

Golden Canon Tables, 6th or 7th century (The British Library)

The Golden Canon Tables were painted around the time that Pope Gregory the Great (c. 540–604) famously chastised the bishop of Marseilles for destroying images of saints in his church. Indeed, St Gregory actively encouraged the use of images, equating pictures with books for the illiterate to ‘read’. Perhaps this argument could be used to explain the illustrated manuscripts made for patrons who may not have been entirely comfortable in Latin, such as the Harley Bible moralisée, with its hundreds of images. When justifying the incorporation of images in Bibles, biblical commentaries and devotional and liturgical works, St Gregory further elucidated the distinction between ‘adoring a picture and learning from its story what is to be adored’.

In the East, however, the point was more contentious. In 726 the Byzantine emperor Leo III the Isarian (r. 717–741) issued an edict declaring all images to be idols and ordering their destruction in what is now known as the Iconoclast (literally, ‘image-breakers’) Controversy. After periods when this policy was temporarily relaxed or reversed, it came to an end formally in 842, with the accession of Empress Theodora (r. 842–856), who restored the use of icons, or images, to be venerated. This event is still celebrated as the Feast of Orthodoxy in the Eastern Church on the first Sunday in Lent. The justification for the reintroduction of images was set out in the Second Council of Nicaea in 787, which declared that:

Also [we declare] that one may render to them [icons] the veneration of honour; not the true worship of our faith, which is due only to the divine nature, but the same kind of veneration as is offered to the form of the precious and life-giving cross, to the holy gospels, and to the other holy dedicated items.[1]

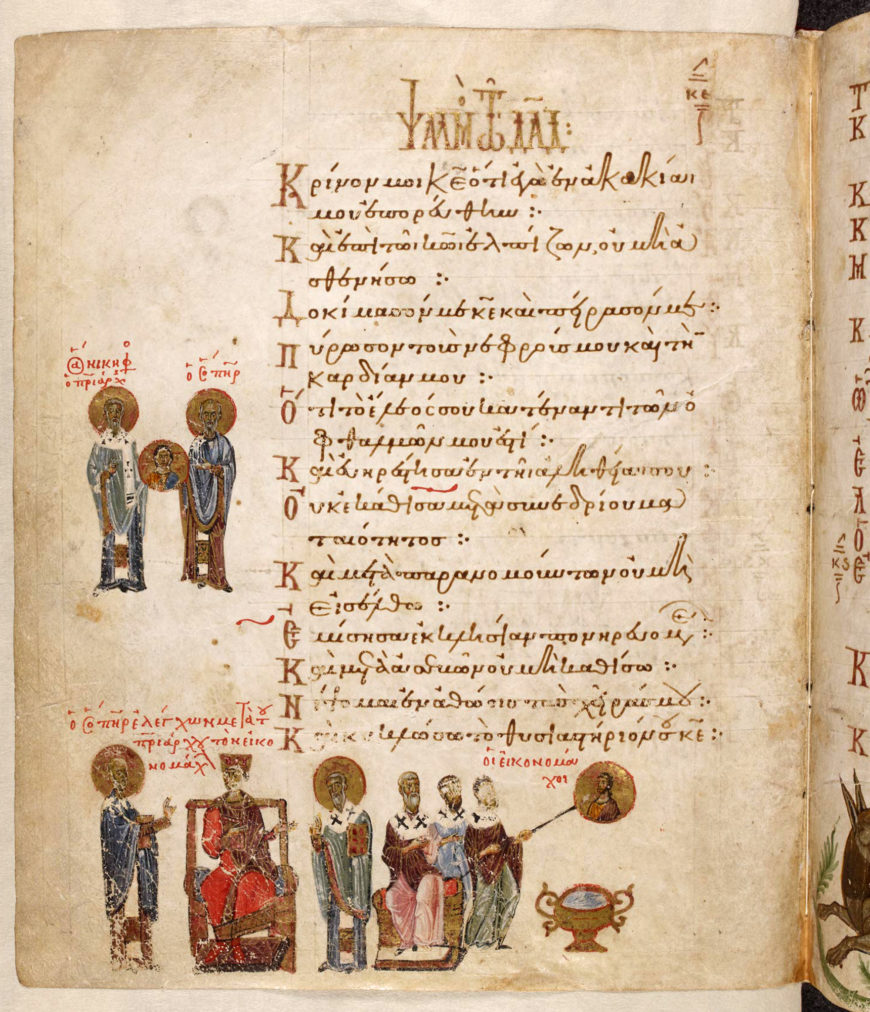

The iconoclasts are represented in a marginal illustration in the Theodore Psalter. Theodore of Caesarea, Theodore Psalter, 1066, Constantinople, parchment, 23 x 22 cm (The British Library)

The elaborately illuminated Theodore Psalter exemplifies the quality of illuminated biblical books created in the Eastern capital following these events. It even includes portraits of the important figures in the debate in its marginal commentaries.

The use of precious metals in Bibles

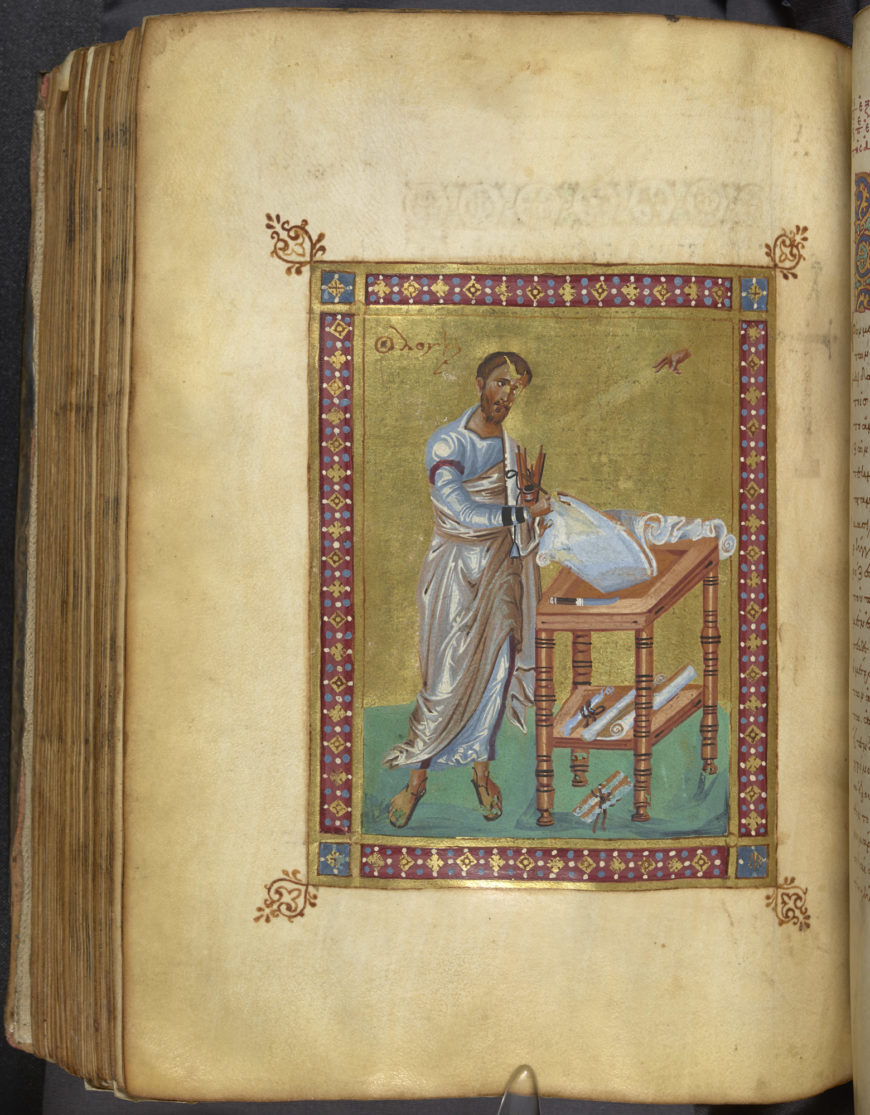

In the most luxurious codices, the biblical text is enhanced further through the use of gold ink or gold leaf. In most manuscripts, gold appears more frequently as gold leaf, typically affixed to a gum and burnished with a polished stone or animal tooth. The result, as seen in the background and details of the illuminated Bibles from the Carolingian period onwards, is spectacular – these images are untarnished, and still shine, centuries after they were made. In a Christian context, the use of precious materials underlines the importance of the text itself. The gold backgrounds create a heavenly setting and place the figures in a spiritual context. Shimmering backgrounds to Evangelist and other author portraits in both Byzantine and Western manuscripts emphasise the divine inspiration of their texts.

A portrait of St Mark, painted on a gold background, in the Burney Gospels. Kokkinobaphos Master (illustrator), Burney Gospels, 10th–12th centuries, parchment, 22 x 17 cm (The British Library)

Stylised calligraphy in biblical illumination

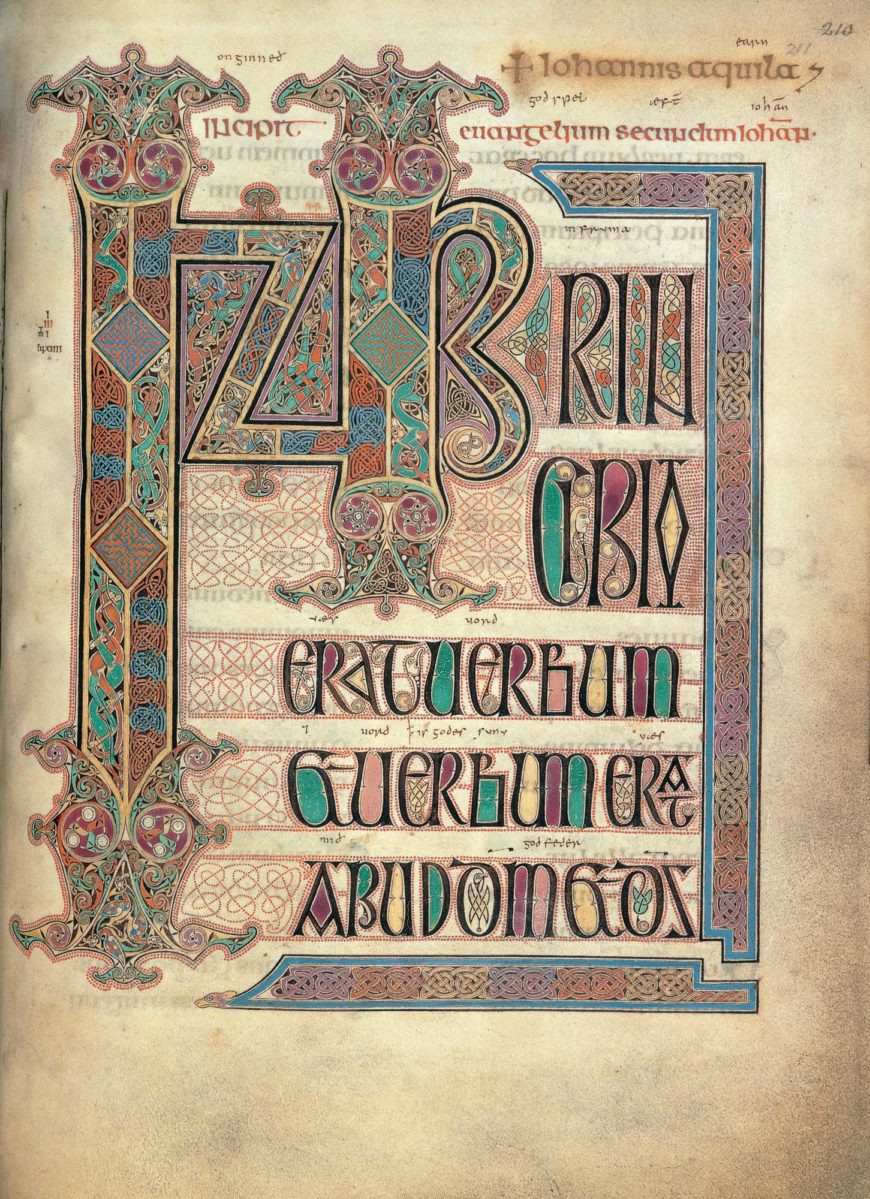

One of the most striking aspects of Bible decoration is the use of stylised calligraphy in different forms to ornament the text, whereby individual letters, and sometimes entire words, become elements of design. In many Latin manuscripts, the initial letter of each biblical book is enlarged and elaborated, often including decorative panels and shapes. An extreme example of this elaboration occurs in the justly famous Lindisfarne Gospels. Here the first words of each Gospel and of St Jerome’s letters are expanded to fill much of the page, and are intricately decorated with complex patterns.

An intricately decorated incipit page, showing the first words of the Gospel of St John, from the Lindisfarne Gospels. The Lindisfarne Gospels, c. 700, parchment, 36.5 x 27.5 cm (The British Library)

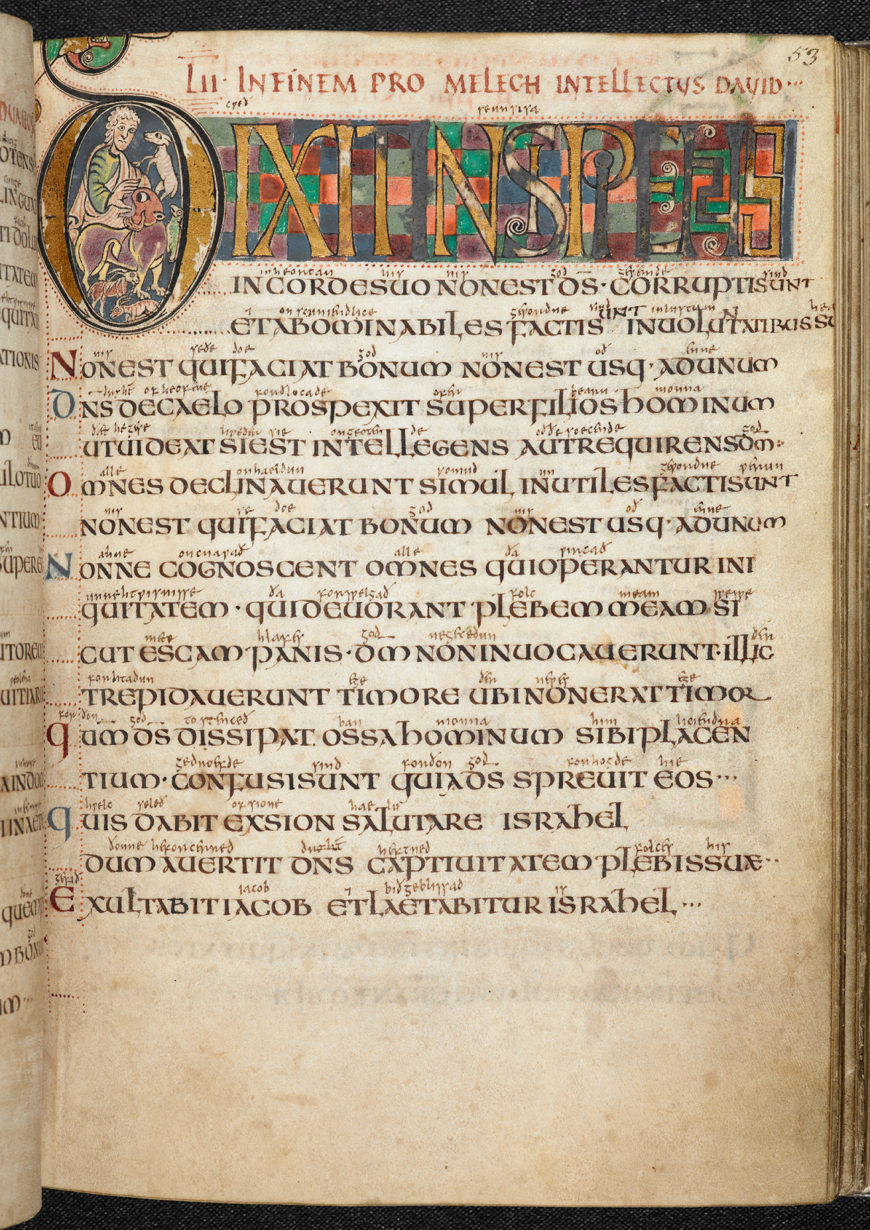

Historiated initials

In addition to calligraphic embellishment, initial letters of words could be ‘historiated’, or decorated with illustrations reflecting or commenting on the story of the text. These commonly occurred at the beginning of biblical books or important psalm divisions. The first example of this in the West occurs in the 8th-century Vespasian Psalter made in Kent, in which depictions of animals are placed between letters and depictions of David are set within the form of the letter itself. The historiated initial quickly became a customary feature of luxury biblical codices for the following 800 years, evident in the 12th-century Winchester Psalter and the 15th-century Great Bible.

A historiated initial D representing David as a shepherd, rescuing a lamb from a lion at the beginning of Psalm 38, from the Vespasian Psalter. Psalter (‘The Vespasian Psalter’), 2nd quarter of the 8th century–mid-9th century (The British Library)

Stylistic influences on biblical paintings

Stylistically, the paintings in Bibles draw on the heritage of the ancient world of Greece and Rome. This is particularly noticeable in the sophisticated painting in the early Christian period, now known from the remains of luxury codices such as the Golden Canon Tables and the Cotton Genesis. In content, too, both the Eastern and Western Church adopted the traditional Antique author portrait to preface the Gospels with Evangelists portraits. In many portraits, the Evangelists were dressed in stylised classical robes. Typically the Evangelists are depicted in the act of writing out their text, holding pens and knives to make corrections, as noted earlier, and often with legible initial words in their open volumes.

A portrait of St Luke. Guest-Coutts New Testament, mid-10th century, parchment, 29 x 20.5 cm (The British Library)

Narrative sequences

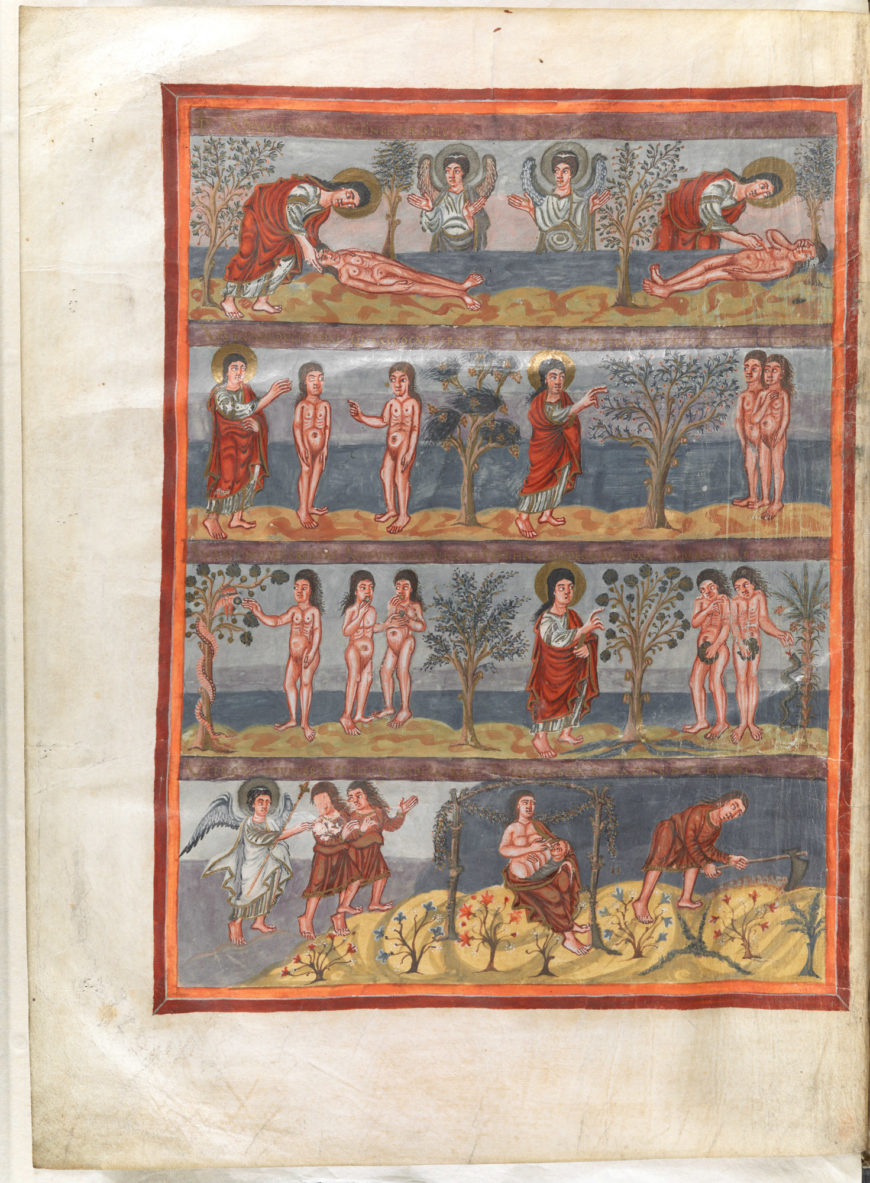

Throughout Christendom other more extensive and exegetical, or narrative, sequences of illustration were employed in Bibles. The massive Carolingian Moutier-Grandval Bible, for example, includes full-page illustrations of events related in Genesis and Exodus, but also more complicated visual commentaries of the relationship between the Old and New Testaments.

A full-page illustration of the Creation of Adam and Eve and the Fall, preceding the Book of Genesis in the Moutier-Grandval Bible. Bible (The ‘Moutier-Grandval Bible’), c. 830–840, parchment (The British Library)

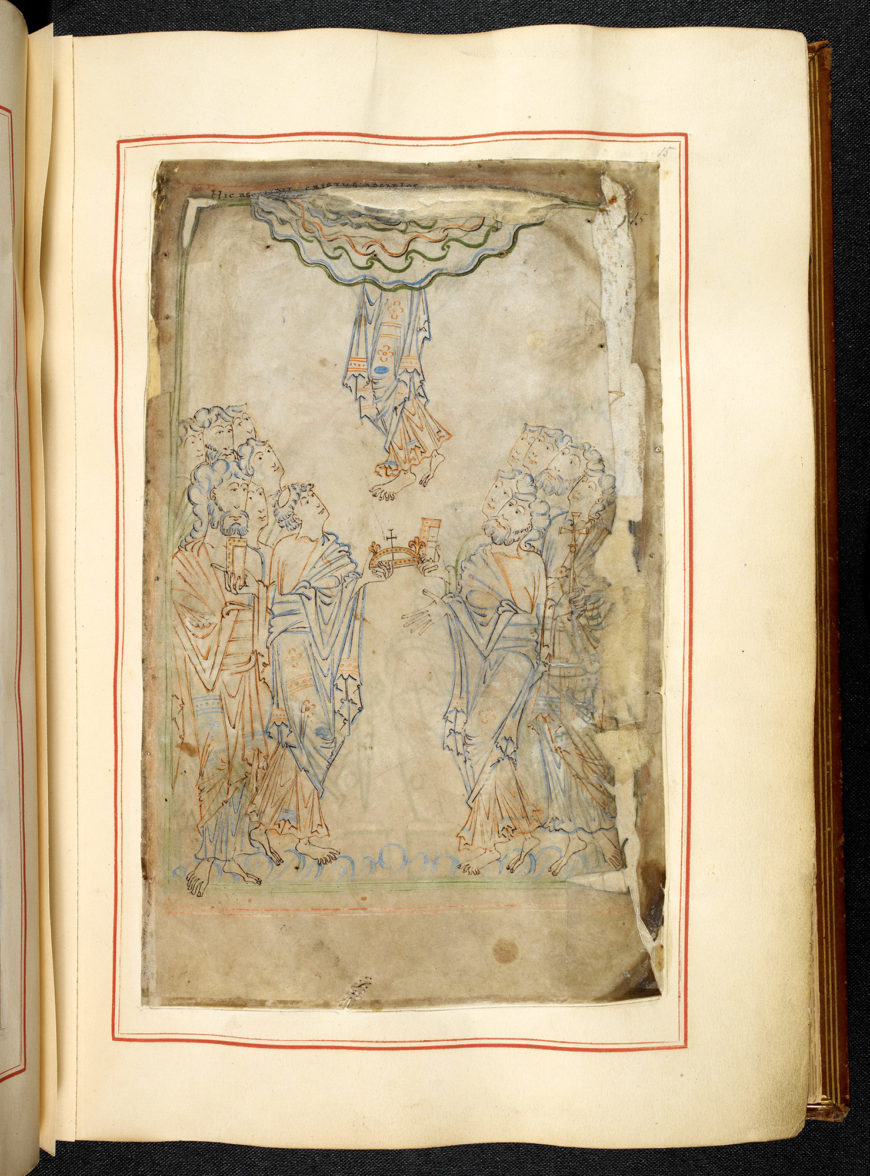

Sometimes these cycles of illumination were incorporated into the body of the text, as in the 13th-century Gospel Lectionary made in Mosul, which includes an extended narrative comprising scenes from the life of Christ. More typically, the illustrations precede the text, as in illustrated psalters where images of Christ’s life and Passion precede the psalms. There they provide an additional devotional context and focus, and emphasise their prophetic nature. The first extensive cycle of prefatory images appeared in the West in the Tiberius Psalter, made in Winchester in the 11th century.

Psalter (the ‘Tiberius Psalter’), 2nd or 3rd quarter of the 11th century (The British Library)

Their use became widespread in luxury psalters throughout the Western Christian world. Another beautiful example is the Winchester Psalter from 12th-century England. Both volumes are reminders that books and other liturgical or devotional objects such as icons, chalices and pyxes were portable, and as a result had a wide circulation, as princely gifts and prized personal devotional possessions.

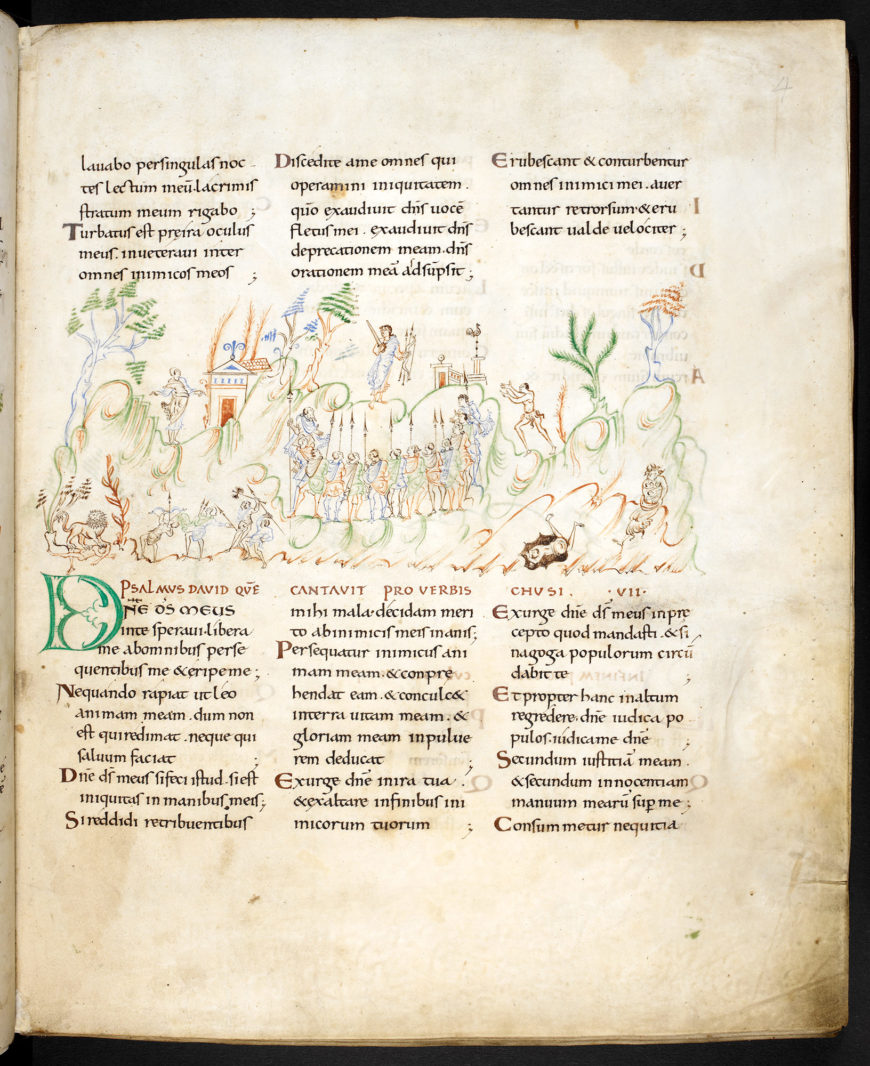

Another approach to illustration is taken in the Harley Psalter, a copy of a famous Carolingian manuscript, in which the accompanying pictures correspond directly to the verses of the Psalms, translating them virtually phrase-by-phrase into visual form.

The Harley Psalter includes over 100 coloured line drawings, illustrating the Psalms. Psalter (the ‘Harley Psalter’), c. 1000, parchment, 38 x 31 cm (The British Library)

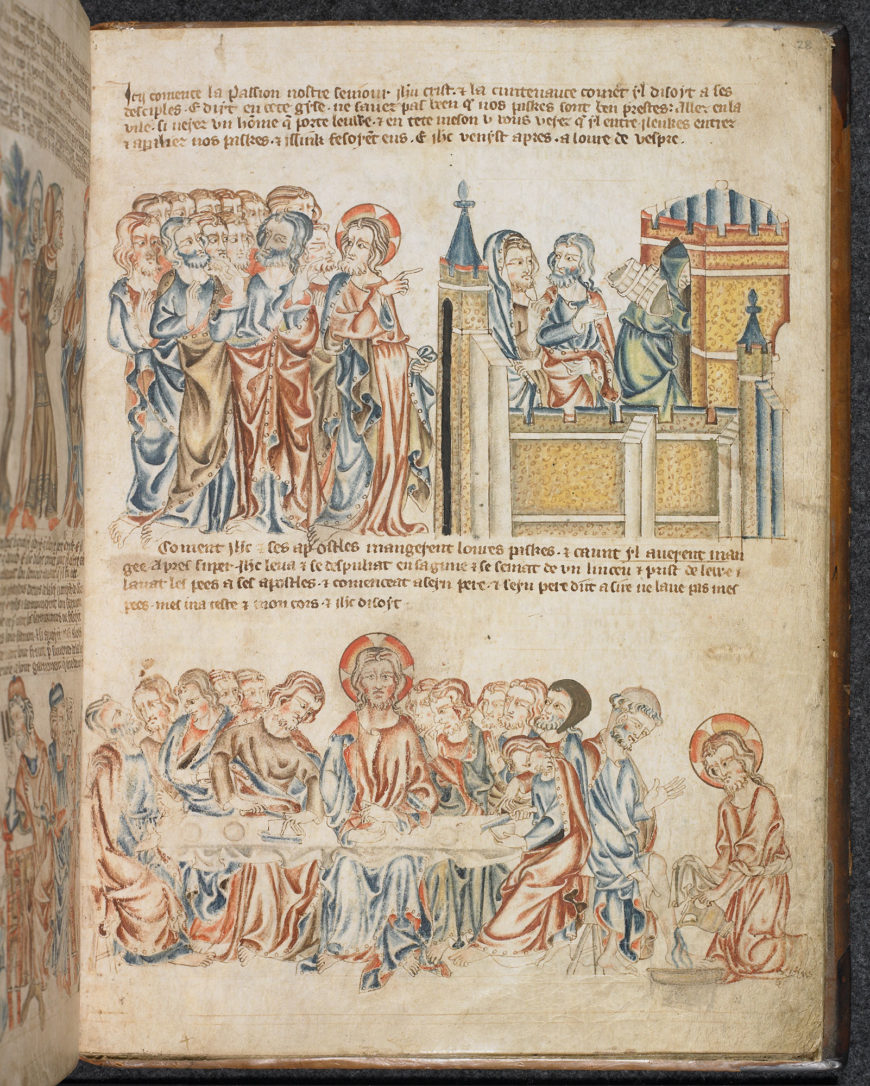

The Last Supper, in Bible (the ‘Holkham Bible Picture Book’), c. 1327–1335, parchment, 28.5 x 21 cm (The British Library)

In other books, probably designed for a lay readership, images dominate, with the biblical text paraphrased or providing captions for biblical picture books. In an important early example, the Old English Hexateuch, the vivid images fill most or all of its pages, accompanied by the earliest surviving translation into English of some parts of the Old Testament. By the 14th century another English example, the Holkham Bible Picture Book, included captions in French. Other 14th- and 15th-century Bibles with more extensive biblical or paraphrased text also appeared in the vernacular.

Written by Dr. Kathleen Doyle

Dr Kathleen Doyle is the Lead Curator of Illuminated Manuscripts at the British Library. She received her PhD in Medieval Art History from the Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London, where her thesis focussed on 12th-century Cistercian manuscripts and the use of images in monastic art. Her latest publications are with Charlotte Denoël, Medieval Illumination: Manuscript Art in England and France 700–1200 (2018), also available in French, and with Scot McKendrick, The Art of the Bible: Illuminated Manuscripts from the Medieval World (2016), which has been translated into Dutch, French, German and Italian.

Dr Doyle was the co-curator, with Dr Scot McKendrick, of the AHRC-funded exhibition, Royal Manuscripts: The Genius of Illumination, and the Lead Investigator for the Royal Manuscripts follow-on project, editing with Dr McKendrick the volume 1000 Years of Royal Books and Manuscripts (2013).

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

Originally published by The British Library.