Yuan dynasty (1279–1368): an introduction

Read Now >Chapter 30

Art under the Mongols

Introduction to the Yuan Dynasty

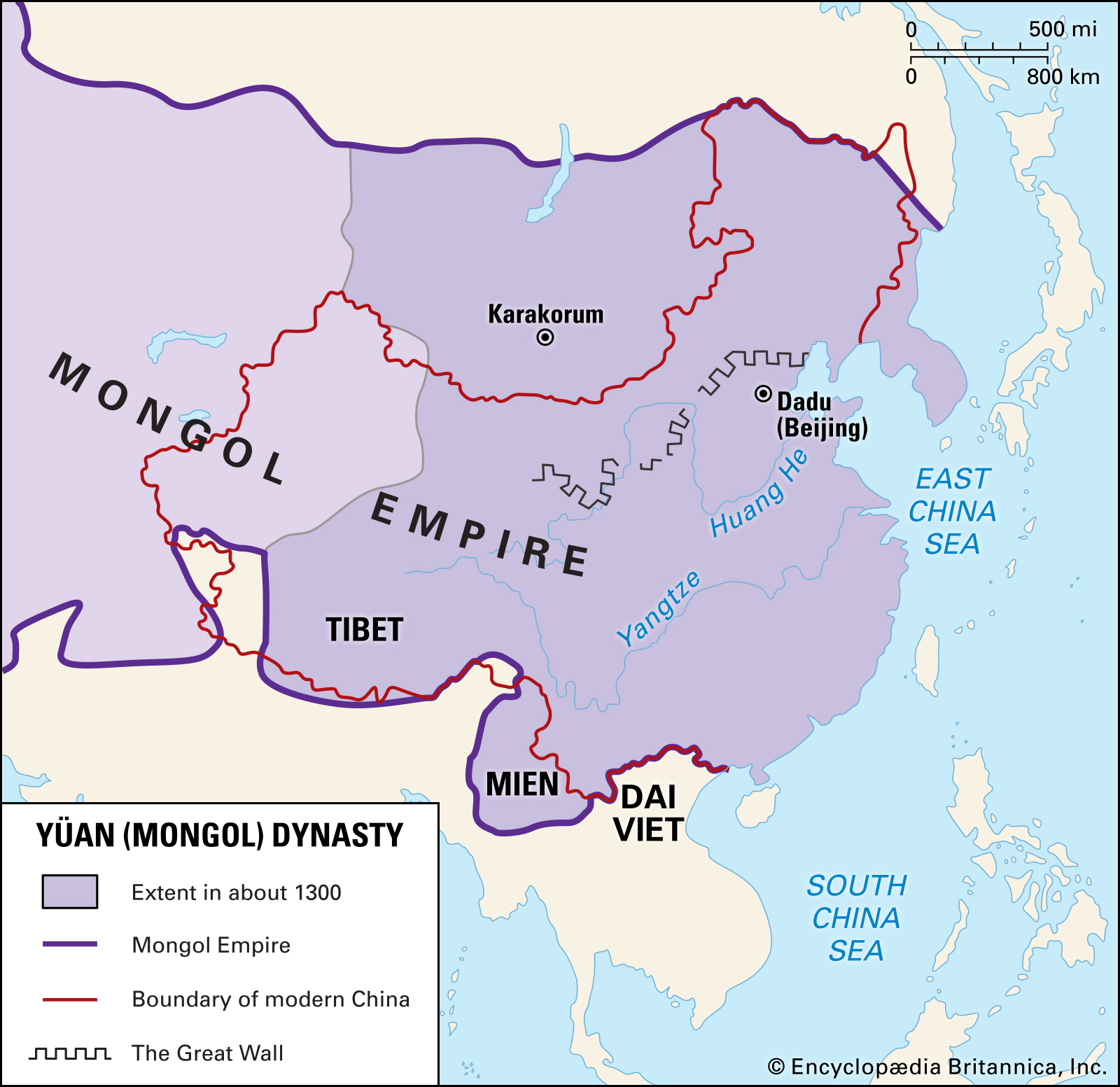

Map of the extent of the Mongol Empire (underlying map © Google)

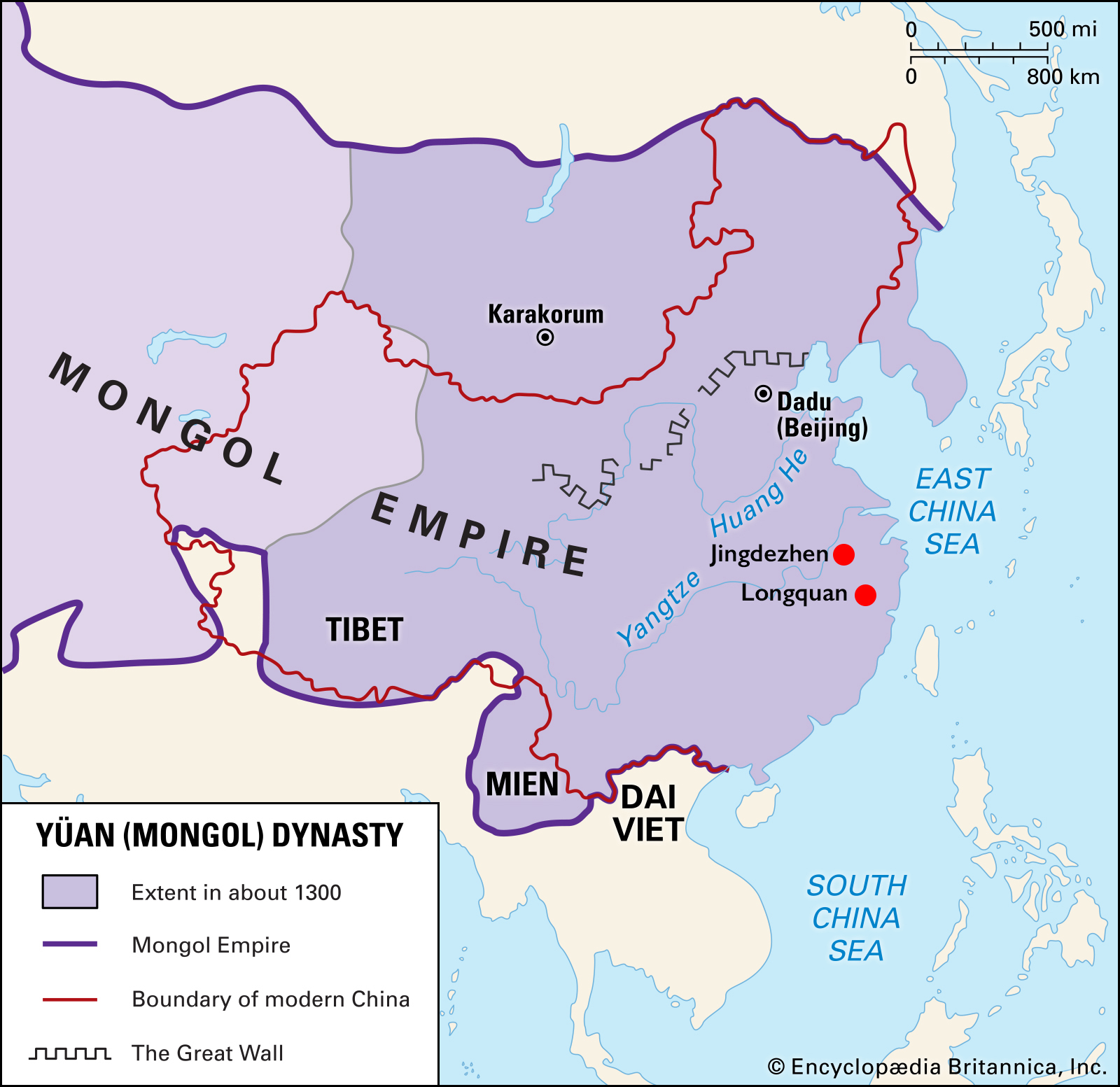

In the 13th century, Genghis Khan, leader and founder of the Mongol nation, was on a quest to conquer the entire Eurasian continent, with an eye on taking China from the non-Chinese Jurchens who occupied north China (and portions of the Yellow River) and from the Southern Song dynasty that ruled over south China. In 1215, Genghis Khan’s fierce and disciplined armies captured Beijing from the Jurchen invaders. However, Genghis Khan did not live to see the ultimate defeat and capture of Southern Song dynasty China. It was only under his grandson Kublai Khan’s leadership that the Yuan dynasty was founded in 1260. Then, in 1279, the Chinese Southern Song dynasty capital at Hangzhou fell to the Mongols, forming the largest empire in world history spanning some 9 million square miles from the Sea of Japan (East Sea) to the Mediterranean. Kublai Khan moved the capital of the Mongol Empire from Karakorum in Central Asia to Shangdu in Inner Mongolia before relocating to Dàdū 大都 in modern day Beijing.

Map of the Yuan Dynasty

After the move of the capital to Dadu, Kublai Khan restructured the class system in China according to ethnicity, placing Mongols and other favored foreigners at the top and Northern and Southern Chinese at the bottom. This change placed the largest ethnic group in China, the Han, in the lowest position. He also temporarily abolished the civil service examination system, a competitive examination system in place since 650 C.E. that was used to recruit officials for public service based on their merit rather than on their personal connections. Kublai appointed people to office and preferred foreigners over the Chinese. This disenfranchised educated Chinese men who used the examination system as a means of upward mobility in society. Many educated Chinese, who had the means to do so, withdrew from society and referred to themselves as yímín 遺民 or “leftover subjects” of the Song dynasty.

Dish with design of mandarin fish, Yuan dynasty, mid 14th century, Jingdezhen ware, porcelain with cobalt pigment under colorless glaze, China, Jiangxi province, Jingdezhen, 8 × 45.5 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, F1971.3)

Despite the social upheaval after the Mongol invasion and the fall of the Southern Song dynasty, the arts flourished during the Yuan dynasty. For example, this period saw significant developments in ink painting as a form of personal self-expression and self-cultivation, as well as in underglaze decorated porcelain. Trade networks across the vast Mongol empire also created unique opportunities for the cross-cultural exchange of ideas, technologies, and artistic styles.

Read an overview

/1 Completed

Painting

When the Mongols invaded China and took over the Song court, they abolished the Imperial Academy of Painting (established during the Northern Song dynasty under Emperor Huizong). Instead, Kublai Khan and his successors appointed and organized skilled artisans into new court agencies responsible for the arts and manufacture of imperial objects. Unsurprisingly, during Kublai’s reign, these agencies were overseen by a foreigner, the Nepali artist Anige. Anige was responsible for the construction and design of many Buddhist stupas, temples, paintings and sculpture under Kublai, who had a deep interest in Buddhism.

Left: Attributed to Nepali artist Anige, Portrait of Kublai Khan, album leaf, Yuan dynasty, 1294, colors and ink on silk, 59.4 x 47 cm (National Palace Museum in Taibei); right: Attributed to Nepali artist Anige, Portrait of Chabi, wife of Kublai Khan, album leaf, colors and ink on silk, Yuan dynasty, 1294, 61.5 x 48 cm (National Palace Museum in Taibei)

Scholar Anning Jing argues that Anige painted the posthumous portraits of Kublai Khan and his wife Chabi because the portraits are painted in a blend of Chinese and Nepali artistic styles. The artist combined traditional Chinese styles of imperial portraiture, which the Mongols valued as a visual means to legitimize their rule as the successors of Han Chinese emperors, with the Himalayan technique of highlighting (seen especially in the highlights on the gemstones in the portrait of Chabi). [1]

Read an essay about painting

Portrait of Chabi: This portrait offers a glimpse into the crucial role played by court dress in the consolidation of Mongol rule across Eurasia.

Read Now >/1 Completed

Attributed to Cheng Qi (傳)程棨 (active mid- to late 13th century), formerly attributed to Liu Songnian (傳)劉松年 (c. 1150–after 1225), Tilling Rice, after Lou Shou, Yuan dynasty, mid- to late 13th century, Ink and color on paper, China, 32.7 x 1049.8 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, F1954.21)

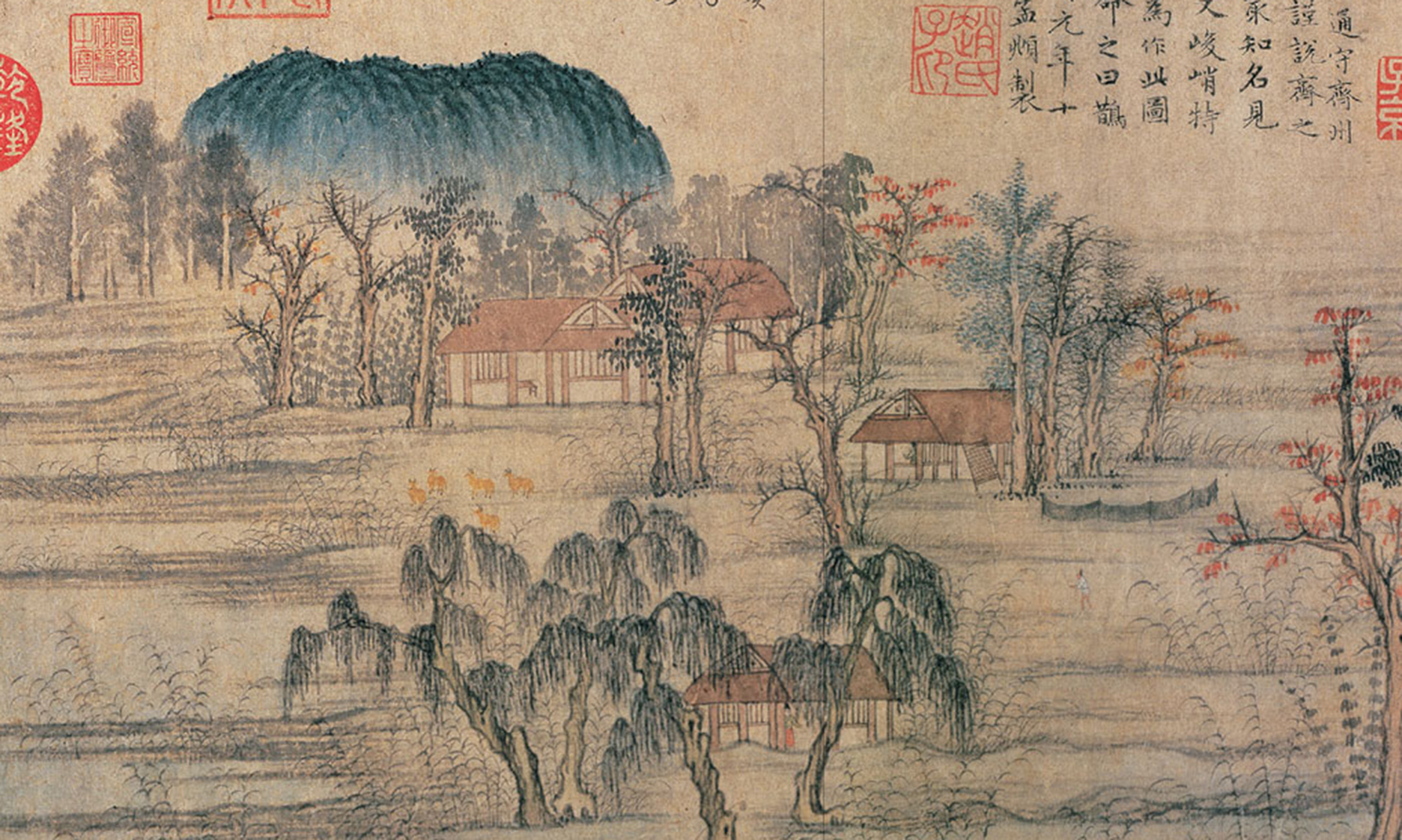

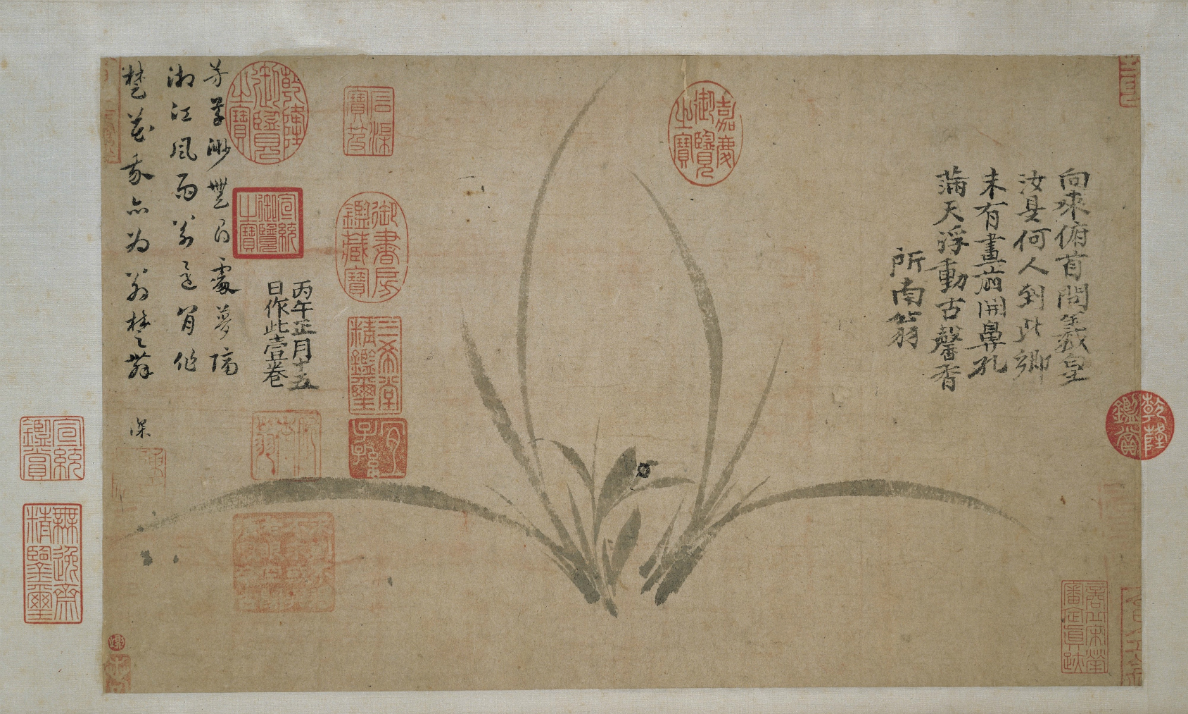

Looking to the past

During the Yuan dynasty, many Han Chinese painters, who were also well-educated scholars and would otherwise have taken the civil service examination, withdrew from society, declaring their loyalty to the fallen Song dynasty. These painters, many of them literati (scholar-amateur) painters, used ink and brush to express their dissatisfaction with Mongol rule. This was often done covertly by reflecting on artistic styles of the past, especially from periods in Chinese history ruled by Han Chinese; or through the depiction of symbolic subject matter, such as bamboo and orchids; or through the copying of symbolic genres of painting, such as the genre of Pictures of Tilling and Weaving, that recalled more stable and prosperous times in Chinese history.

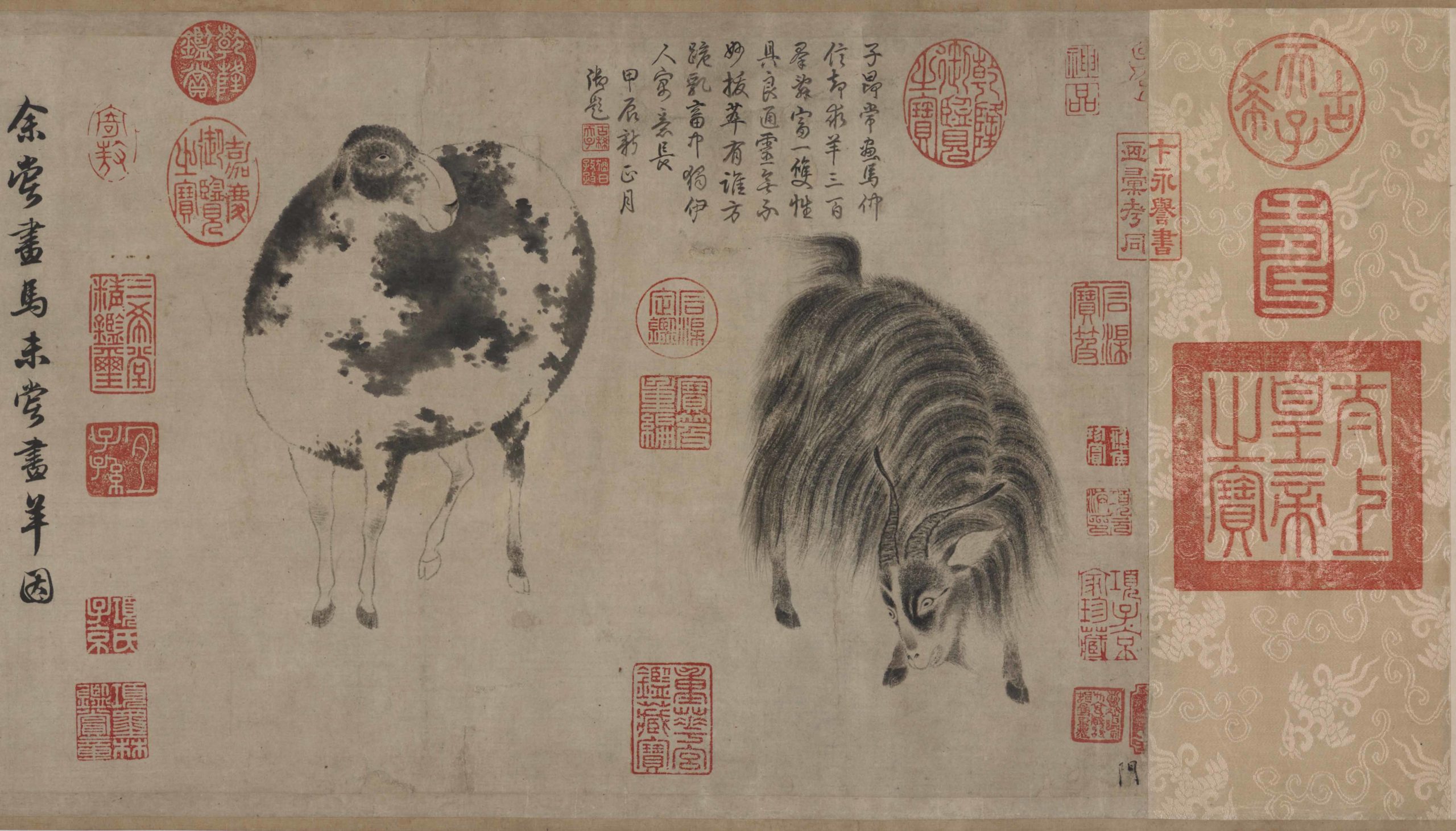

Zhao Mengfu 趙孟頫 (1254–1322), Sheep and Goat (detail), Yuan dynasty, c. 1300, ink on paper, China, 25.2 x 48.7 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, F1931.4)

This section introduces five early Yuan painters, who lived through the fall of the Song dynasty and used painting to respond to the dramatic loss of stability with the transition to a non-Chinese Mongol ruled government. One painter, Zhao Mengfu, accepted an invitation to work at the court of Kublai Khan in the Ministry of War, and was considered to be a traitor in the eyes of Song loyalists. However, like many of his loyalist contemporaries, Zhao found solace in painting. How did each of these artists use the past to express dissatisfaction with the present?

Read about paintings that look to the past

Zhao Mengfu, Autumn Colors on the Que and Hua Mountains: Zhao’s experience as an official of the Yuan dynasty provided him with opportunities to go back and forth between the South and the North.

Read Now >

Attributed to Cheng Qi, Tilling Rice, after Lou Shou: This scroll was copied during the Yuan dynasty when the genre as a symbol for political stability and economic prosperity was probably needed the most.

Read Now >

Qian Xuan, Young Nobleman on Horseback: The artist of this handscroll revived past styles of painting to remind him of China’s glorious past.

Read Now >

Zheng Sixiao, Ink Orchid: Zheng’s painting evoked his sentiments at a tumultuous time in Chinese history.

Read Now >

Xie Chufang, Fascination of Nature: The handscroll symbolizes the beauty and brightness of the natural world to cover up the confusion and disorder caused by the fight for survival.

Read Now >/5 Completed

The reclusive life in painting

Later, the late Ming dynasty (1368–1644) literati painter and art critic Dong Qichang designated Huang Gongwang, Ni Zan, Wu Zhen, and Wang Meng as the Four Great Masters of Yuan painting, making them among the most highly revered painters of later Ming and Qing literati. Their influence was so impactful that contemporary artists like Xu Bing have continued to take inspiration from their work.

“The Remaining Mountain,” Huang Gongwang, Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains (detail), 1350, handscroll, ink on paper, 31.8 x 51.4 cm (Zhejiang Provincial Museum, Hangzhou)

Huang Gongwang

Huang Gongwang, a scholar official who eventually retired to become a rustic Daoist in the mountains, is best known for his monochrome ink landscape painting Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains, a handscroll painting over 22 feet long that took between three and four years to complete because of Huang’s characteristic methodology of only painting when he felt inspired. Huang is known for the spontaneity of his brushwork, which later artists of the Ming and Qing dynasties tried to attain through extensive copying of Huang’s landscapes. In Dwelling the Fuchun Mountains, Huang draws contrasts between wet and dry brushstrokes, and light and dark ink tones, which help guide the viewer’s eyes through deep layers of space. What terms can we use to describe Huang’s methods and techniques? How is a handscroll meant to be viewed?

Read about Huang Gongwang

Huang Gongwang, Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains: Huang’s influence on later generations of literati painters was enormous.

Read Now >/1 Completed

Wu Zhen

Although well educated, the painter Wu Zhen was a recluse who never pursued public service. He chose instead to live a humble life practicing divination (fortune telling) and selling his ink paintings to earn a living. Wu Zhen was known for his paintings of bamboo, a symbol of resilience (bamboo is known to bend but not to break), as well as scenes of fishermen drifting lazily down placid rivers. During the Yuan period, fishing was a metaphor for the reclusive life, where one could escape the harsh realities of human society and life under Mongol rule. How does Wu Zhen convey a sense of solitude and ease in his long handscroll Fishermen, after Jing Hao?

Read about Wu Zhen

Wu Zhen, Fishermen, after Jing Hao: Scholar hermits as fishermen boating on a river is one of Wu’s favorite painting themes.

Read Now >/1 Completed

Ni Zan

The artist Ni Zan lived in relative comfort as a wealthy, well-educated landowner in south China. He avoided public service and instead devoted himself to intellectual and artistic pursuits, which included amassing a personal collection of paintings, calligraphy, and antiquities. In the 1330s, Ni Zan and his family lost their wealth and property due to the oppressive taxes that the Mongol government placed on wealthy Han families. Eventually, after peasant revolts in south China further disrupted his life, he and his family moved onto a houseboat where they wandered waterways for 20 years. Of all the painters of the Yuan dynasty, Ni Zan is one of the most self-expressive.

Ni Zan, Rongxi Studio, 1372, Yuan dynasty, anging scroll, ink on paper, 74.7 x 35.5 cm (National Palace Museum, Taipei)

The sparse landscapes he painted later in life, like the ink painting Rongxi Studio, are plain and unpeopled, symbolic of his isolation and disengagement from society. They are executed with sketchy, dry brushwork, with a formulaic composition of land and trees (and sometimes a pavilion) in the foreground, water (rendered by blank paper) in the midground, and mountains in the background. Ni Zan’s simple, minimalist style can also be seen in his bamboo paintings, where his underlying motivation of self-expression is apparent in his calligraphic strokes.

Read about Ni Zan

Ni Zan, A Branch of Bamboo: Small in scale, it is ideal for the artist to express his thoughts and to take the viewer into an intimate and spiritual realm.

Read Now >/1 Completed

Wang Meng

The artist Wang Meng was the grandson of the early Yuan painter Zhao Mengfu. Following in his grandfather’s footsteps, Wang Meng served as an official in a minor post. However, when the rebel group known as the Red Turbans took control of the Jiangnan region of China where Wang Meng lived, he chose to withdraw from society rather than join the peasant rebellion. After the Yuan dynasty fell in 1368, he reemerged and took another official post. Unfortunately, he was eventually imprisoned by the paranoid and anti-intellectual first emperor of the Ming dynasty, Emperor Hongwu (Zhu Yuanzhang), who charged many intellectuals with sedition and had them executed.

Wang Meng, Forest Chamber Grotto at Juqu, 14th century, Yuan dynasty, ink and colors on paper, 68.7 x 42.5 cm (National Palace Museum, Taipei)

Where Ni Zan’s paintings are sparse, Wang Meng’s are filled with densely packed brushstrokes. In Forest Grotto at Juqu, Wang Meng depicts a secluded grotto scene. The rocky face of the grotto is composed of dynamic twists and ambiguous turns, conveying a sense of unease. Small timber cabins are tucked into the landscape, their accesses hidden from the viewer, but with robed scholars seated comfortably within.

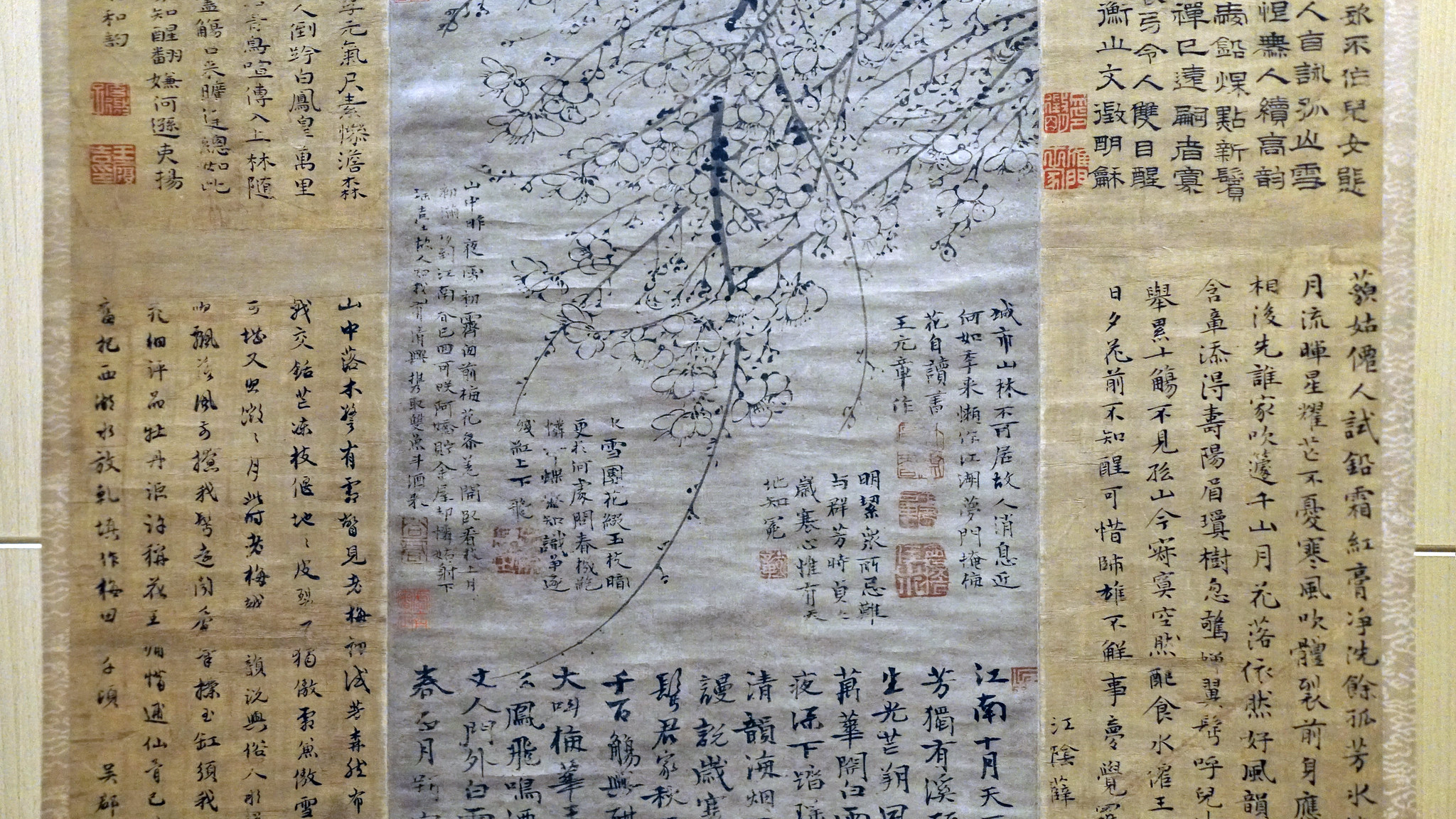

Perseverance in Painting

Beyond Dong Qichang’s Four Great Masters of the Yuan, there were many literati painters who made important contributions to the field of ink painting through their own specializations. One such artist is Wang Mian who devoted his life to painting plum blossoms after failing to achieve a career in public service. He made a living selling his ink plum paintings, as plum blossoms were a popular motif during the Yuan dynasty. One of the “Four Gentlemen,” plum blossoms symbolized resiliency and perseverance in times of adversity.

Watch a video about Wang Mian

Wang Mian, Plum Blossoms in Ink: The flowering plum blossom became a symbol of perseverance in times of adversity.

Read Now >/1 Completed

Decorative Arts

Map of the Longquan kilns in Zhejiang and the Jingdezhen kilns in Jiangxi

The production of ceramics continued to thrive under Yuan supervision. Ceramic production for both domestic consumption and export abroad was mainly concentrated at the Longquan kilns in Zhejiang and the Jingdezhen kilns in Jiangxi. The technique of underglaze painted decoration was revived in copper red, derived from copper-oxide, and cobalt blue, sourced from present-day Iran.

Bottle with Peonies, mid-14th century (Yuan dynasty), porcelain painted with copper red under transparent glaze (Jingdezhen ware), 24.1 x 12.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Underglaze blue-and-white porcelains were especially popular with export markets in the Near East. Underglaze painted ceramics were durable and painted decoration could be adapted to the tastes of the consumer, whether made as a dedication to a Daoist temple in China, for the use of Zen Buddhist monks in Japan, or for Muslim consumers in West Asia. Demand for underglaze blue-and-white porcelain abroad was stimulated by the open trade routes and the global connections of the vast Mongol empire.

Watch a video about porcelain in the Yuan dynasty

/1 Completed

Confluence of Cultures

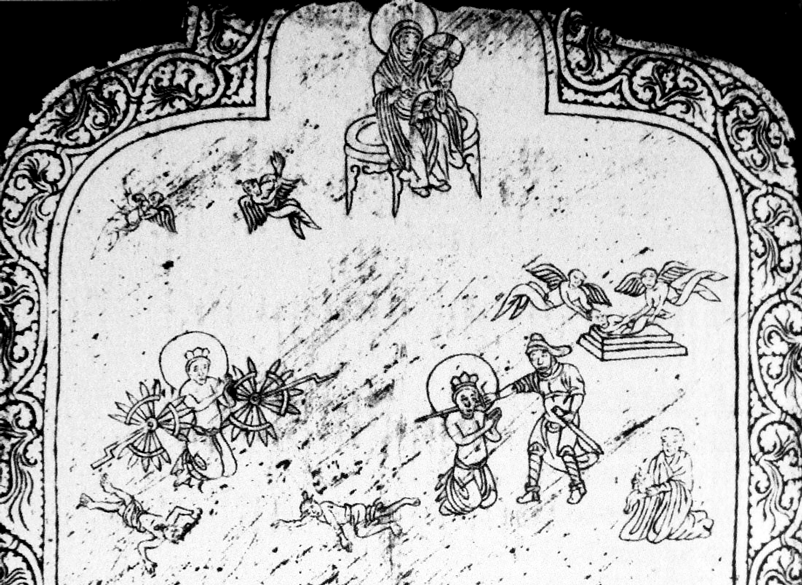

Caterina Vilioni’s Tombstone, 1342, stone (Yangzhou Museum)

During the Yuan dynasty, travelers from abroad took advantage of the network of trade routes across Eurasia. Along with the Venetian merchant Marco Polo who arrived at the Mongol court around 1275 and stayed for 16 or 17 years, there is evidence that many Europeans lived in China during the Yuan dynasty. Tombstones like the one belonging to Caterina Vilioni, a Christian immigrant from Italy who settled permanently in China in the thirteenth century, give us important insight into religious plurality and tolerance in Yuan dynasty China. How does the narrative scene depicted on Caterina Vilioni’s tombstone show the confluence of Chinese and European artistic styles and subject matter?

Read about cultural confluence in the Yuan dynasty

Caterina Vilioni’s tomb in Yangzhou: Caterina Vilioni’s tombstone offers invaluable insight to the presence of Christian and especially of European women in thirteenth-century China.

Read Now >/1 Completed

In the arts, the Yuan dynasty is a period in Chinese history marked by self-reflection and exploration in a time of social upheaval under the new Mongol regime. Chinese painters used ink and brush to express complicated emotions over the present situation and nostalgia for better times. At the same time, the international connections of the Mongol regime prompted a new engagement with foreign ideas and tastes, both in the demand for Chinese porcelain abroad and in the confluence of cultures domestically.

Notes:

[1] Anning Jing, “The Portraits of Khubilai Khan and Chabi by Anige (1245-1306), a Nepali Artist at the Yuan Court,” Artibus Asiae 54, no. 1/2 (1994): pp. 40–86.

Key questions to guide your reading

How did the Mongol conquest of China impact Chinese society and the arts?

What was the function of ink painting during the Yuan dynasty? What themes were important in Yuan dynasty painting and why?

How did the Mongol conquest of China impact trade and the production of ceramics during the Yuan dynasty?

How did the Mongol conquest of China stimulate cross-cultural exchange?

Jump down to Terms to KnowHow did the Mongol conquest of China impact Chinese society and the arts?

What was the function of ink painting during the Yuan dynasty? What themes were important in Yuan dynasty painting and why?

How did the Mongol conquest of China impact trade and the production of ceramics during the Yuan dynasty?

How did the Mongol conquest of China stimulate cross-cultural exchange?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

literati

self-cultivation

yimin

Four Gentlemen

porcelain

underglaze

Learn more

Check out contemporary artist Xu Bing’s Background Story: Landscape After Huang Gongwang

Barnhart, Richard M. et al. Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997).

Jing, Anning. “The Portraits of Khubilai Khan and Chabi by Anige (1245-1306), a Nepali Artist at the Yuan Court.” Artibus Asiae 54, no. 1/2 (1994): 40-86.