The first step—soaking the seeds. Attributed to Cheng Qi (傳)程棨 (active mid- to late 13th century), formerly attributed to Liu Songnian (傳)劉松年 (c. 1150–after 1225), Tilling Rice, after Lou Shou (detail), Yuan dynasty, mid- to late 13th century, ink and color on paper, China, 32.7 x 1049.8 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, F1954.21)

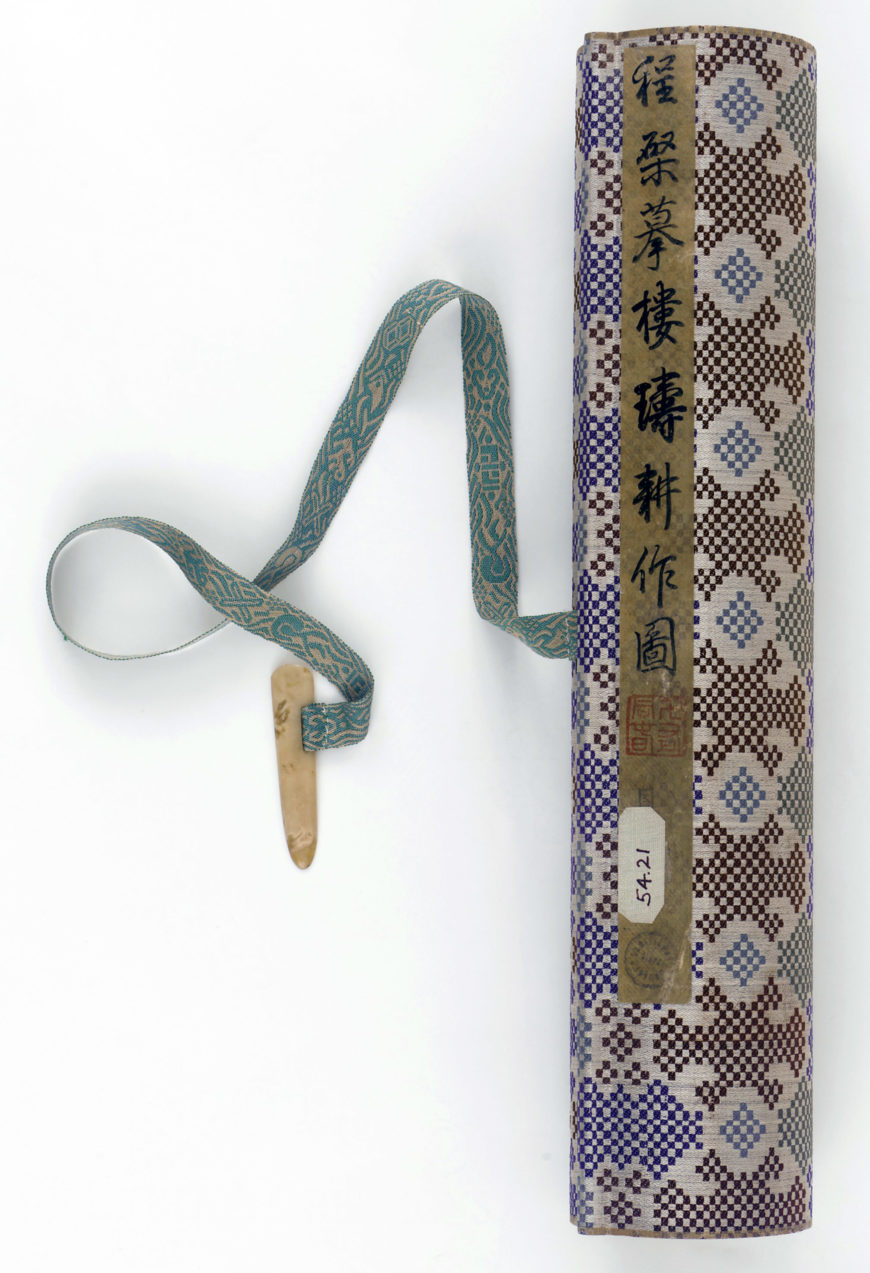

This handscroll is almost thirty-five feet long. It illustrates the twenty-one steps of producing rice. For each section you unroll, you will see an image and an accompanying poem describing one of the steps.

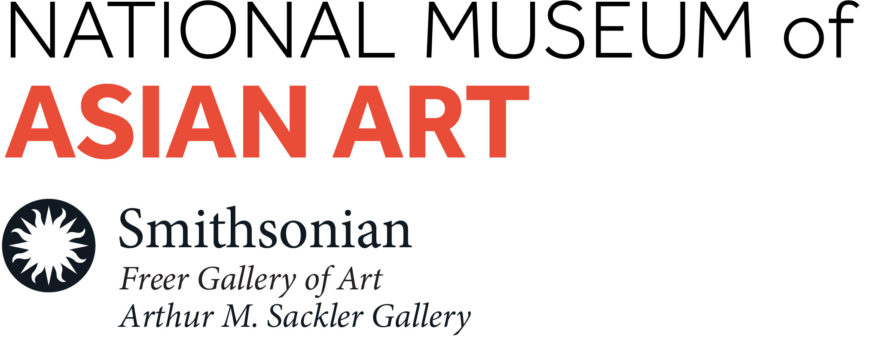

Steps two and three—plowing and raking (from right to left). Attributed to Cheng Qi (傳)程棨 (active mid- to late 13th century), formerly attributed to Liu Songnian (傳)劉松年 (c. 1150–after 1225), Tilling Rice, after Lou Shou (detail), Yuan dynasty, mid- to late 13th century, ink and color on paper, China, 32.7 x 1049.8 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, F1954.21)

The steps are, from right to left, soaking the seeds, plowing, raking, harrowing, rolling, sowing, fertilizing, uprooting the seedlings, transplanting, first weeding, second weeding, third weeding, irrigating, harvesting, stacking, threshing, winnowing, hulling, grinding, sifting, and storing in the granary. Mainly for illustrative purposes, the images are made lively by delightful details.

Step seventeen—winnowing. It includes a detail of a woman breastfeeding her baby as her other child outstretches his arms to her. Attributed to Cheng Qi (傳)程棨 (active mid- to late 13th century) Formerly attributed to Liu Songnian (傳)劉松年 (c. 1150–after 1225), Tilling Rice, after Lou Shou (detail), Yuan dynasty, mid- to late 13th century, ink and color on paper, China, 32.7 x 1049.8 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, F1954.21)

For example, in the winnowing section, a young mom is breastfeeding her baby while her elder boy craves for her attention. The accompanying poems are written in decorative seal script, an ancient writing style now only used for decorative engraving or seals. Smaller characters in standard script, the typeface for most modern printed materials, are added at the side for easier reading. A second poem appears with each section, composed and inscribed by the Qianlong emperor (reigned 1735–96) hundreds of years after the artwork was created.

Attributed to Cheng Qi (傳)程棨 (active mid- to late 13th century), formerly attributed to Liu Songnian (傳)劉松年 (c. 1150–after 1225), Tilling Rice, after Lou Shou, Yuan dynasty, mid- to late 13th century, ink and color on paper, China, 32.7 x 1049.8 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, F1954.21)

This painting shows the work that is required in rice cultivation throughout the seasons. Traditionally, a painting of growing rice is paired with another in a similar format that is dedicated to the production of silk. This genre of painting is known as Pictures of Tilling and Weaving, which were first created during the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279) by an official named Lou Shou. Together, they depict two of the most important activities basic to the livelihood of the Chinese people since early times. The ruling class of succeeding dynasties considered the set to have significant public value: they depicted the ideal of a well-ordered society under well-balanced imperial rule. Emperors repeatedly commissioned copies of the genre. This particular scroll was copied during the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368) when the genre as a symbol for political stability and economic prosperity was probably needed the most.

The handscroll rolled up. Attributed to Cheng Qi (傳)程棨 (active mid- to late 13th century) Formerly attributed to Liu Songnian (傳)劉松年 (c. 1150–after 1225), Tilling Rice, after Lou Shou (detail), Yuan dynasty, mid- to late 13th century, ink and color on paper, China, 32.7 x 1049.8 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, F1954.21)

The Qianlong emperor greatly prized his copy of this scroll. Not only did he compose a second set of twenty-one poems and inscribe them directly on the images, he also wrote two frontispieces introducing and praising the painting. Furthermore, he impressed sixty-two collector seals over the length of the scroll, asserting his approval and ownership. The Qianlong emperor certainly recognized this painting genre’s value in maintaining a thriving state.

- Choose one image in the handscroll and describe what is happening in the image with as much detail as possible. What can you understand from the image about that step in the rice cultivation process? What questions does the image raise for you, and what further information would you like to know about how rice is grown and harvested?

- This handscroll has multiple functions, such as being a beautiful art object, a practical instruction manual for cultivating rice, and an example of a political philosophy. Choose one of these functions and explain why you believe it is the most important, or the one the artist primarily intended, and explain your reasoning.

- Research the importance of rice in Chinese culture in the past and present. Compare and contrast rice-based and wheat-based cultures you have studied in world history. What environmental or social factors determine the primary food that a society eats?