Nara period: an introduction

Read Now >Chapter 45

The four seasons in the arts of Japan

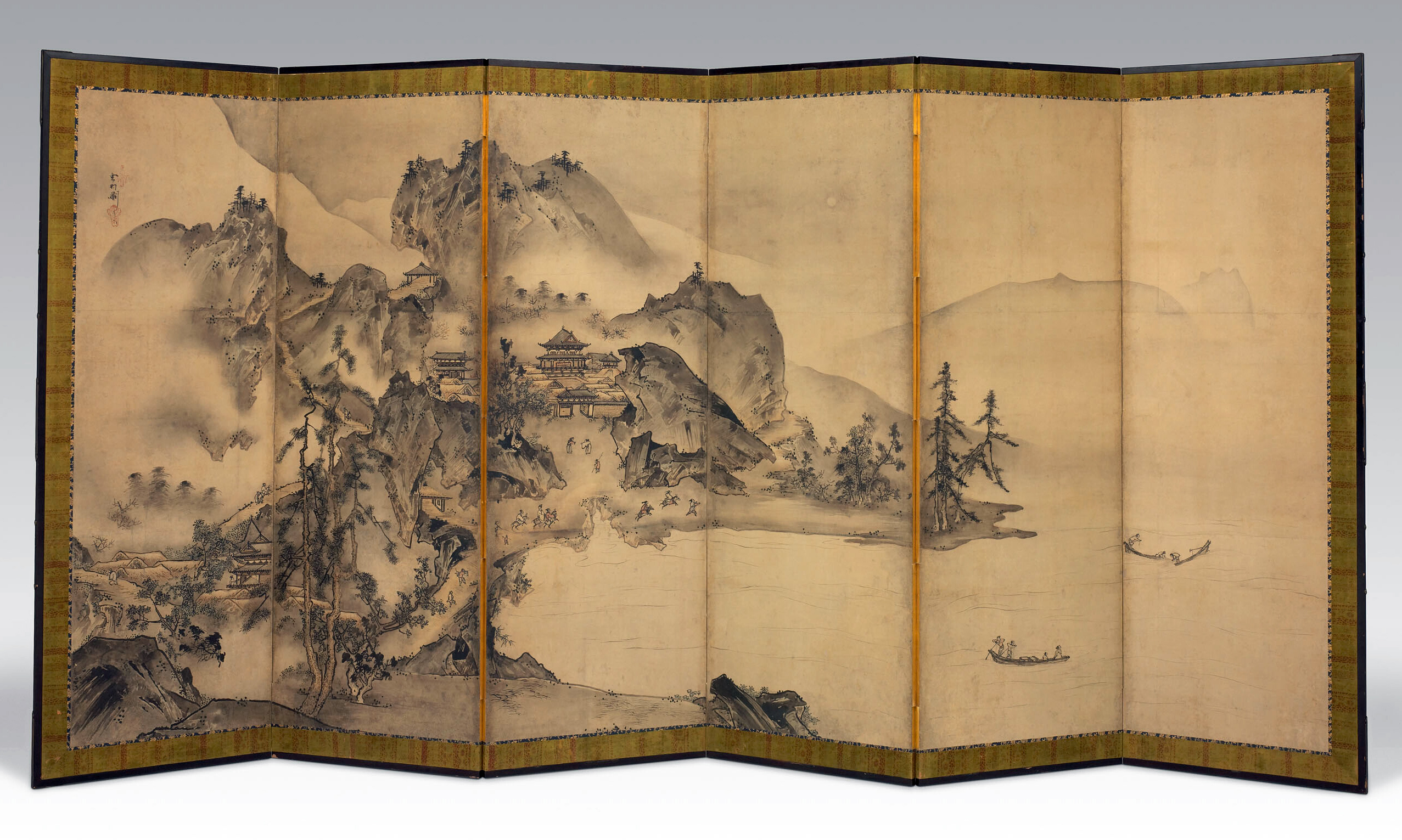

Sesson Shukei, Landscape of the Four Seasons, c. 1560, six-panel screen (one of a pair); ink and light colors on paper, 156.5 cm × 337 cm (Art Institute of Chicago)

Even when looking closely at this painted folding screen by Sesson Shukei, one barely notices the first plum blossoms of spring blooming on trees that dot the landscape on the right side. As we move to the far left, we can see a snow-covered mountain that suggests deep winter. Throughout the landscape, people are engaged in day-to-day activities, fishing, walking, and riding horses, yet all of these activities are shown occurring over the course of four seasons. Paintings like Shukei’s—that envision a single landscape transformed through the four seasons—is a distinctly Japanese artistic phenomenon.

Sake Ewer (Hisage) with Chrysanthemums and Paulownia Crests in Alternating Fields, early 17th century (Momoyama period), lacquered wood with gold hiramaki-e and e-nashiji (“pear-skin picture”) on black ground, Japan, 25.4 cm x 25.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Japanese artists have also taken other approaches to visualizing nature and the four seasons, with some only hinting at the ephemerality of the seasons. A seventeenth-century lacquerware ewer, for instance, pairs chrysanthemums (that bloom in summer) and paulownia (that bloom in spring). Visual references to the changing seasons may also be shown subtly—a single branch of a tree might show a few budding blossoms, the lightest dust of snow, or mists obscuring our view of it.

Regardless of the different ways artists have chosen to visualize seasonal transformation, one thing is clear: nature and the seasons have played a vital role as a source of inspiration and subject matter in the arts of Japan for thousands of years. Interest in the rhythm of the four seasons specifically is one of the oldest and most enduring topics in Japanese poetry, painting and calligraphy, ceramics and lacquerware, and many other forms of craftsmanship and artistic expression. Seasons have stood for the endless cycles of nature, the impermanence of each season as it gives way to the next, and the spiritual and social calendar of season-specific rituals and festivals that articulate the year. Poets have even developed entire anthologies that focused on nature and the seasons, and used them as a way to explore the passage of time and human emotion.

Interest in nature and the ephemerality of the four seasons was also tied to different religious belief systems in Japan, including Shintō (a religion native to Japan) and Buddhism (introduced to Japan in the 6th century). Both demonstrate an interest in the changing seasons and how this affects nature, as well as the ways that the divine could manifest itself in the landscape. In Shintō, deities are believed to live in springs, rivers, trees, and mountains, imbuing nature with divinity, and of course these natural features changed with each passing month. For Buddhists, the fleeting nature of the seasons was also a reminder of change and the transience of things—an important concept in Buddhism. Shintō and Buddhist beliefs would become intertwined in Japan, and paintings such as Shukei’s folding screen and lacquerware objects such as the sake ewer above can encompass a wide set of ideas about nature, beauty, and the cycle of the seasons.

This chapter explores the representation and evocation of the four seasons in Japanese arts across periods and mediums (though primarily in painting), through the lens of religious belief systems, sociocultural practices, and related literary and artistic traditions.

The four seasons through Shintō and Buddhist lenses

Izumo Taisha (Izumo Grand Shrine), considered the oldest Shintō shrine in Japan, dedicated to Okuninushi, the creator of the land of Japan per Shintō beliefs. Izumotaisha Grand Shrine entrance, Japan (photo: Raita Futo, CC BY 2.0)

Shintō

Nature is central to Shintō, a set of beliefs and practices that developed in Japan sometime around the late 1st century B.C.E. In Shintō, everything is believed to be held together by a network of connections—nature and people, animate and inanimate things, and material and spiritual elements. They all communicate within the same field of existence. Deities (kami) inhabit objects and natural elements, and people pay their respects to them, honoring them with ceremonies and worshipping outdoors at important sites. Ritual leaders also aided communities by acting as intermediaries with the kami, helping to bring rain and grow food. Harmony with the kami—and so nature—remains central to Shintō belief.

Although the date of its initial construction is not known (the shrine was probably rebuilt multiple times), the current structure dates from 1744. Izumo Taisha (“the grand shrine of Izumo”), considered the oldest Shintō shrine in Japan, dedicated to Okuninushi, the creator of the land of Japan per Shintō beliefs. General view of the Izumotaisha Grand Shrine, current buildings date to 1744, Japan (photo: CC0 1.0)

Shrines were also built to appease, honor, and otherwise communicate with deities. For example, the Izumotaisha is one of the oldest Shintō shrines in Japan, dedicated to Okuninushi-no-Kami, the deity believed to have built Japan. Shintō shrines like this one were typically built in nature, often on mountains or deep within a forest. They are often built of wood, and so with time have to be remade, as the wood decays with age—yet another reminder of the passage of time and the transformation of nature. A shrine like Izumotaisha helped to mark a place as sacred, and would have reminded anyone approaching it to pay their respects.

Map showing Buddhism spreading to Japan, with some important centers marked (underlying map © Google)

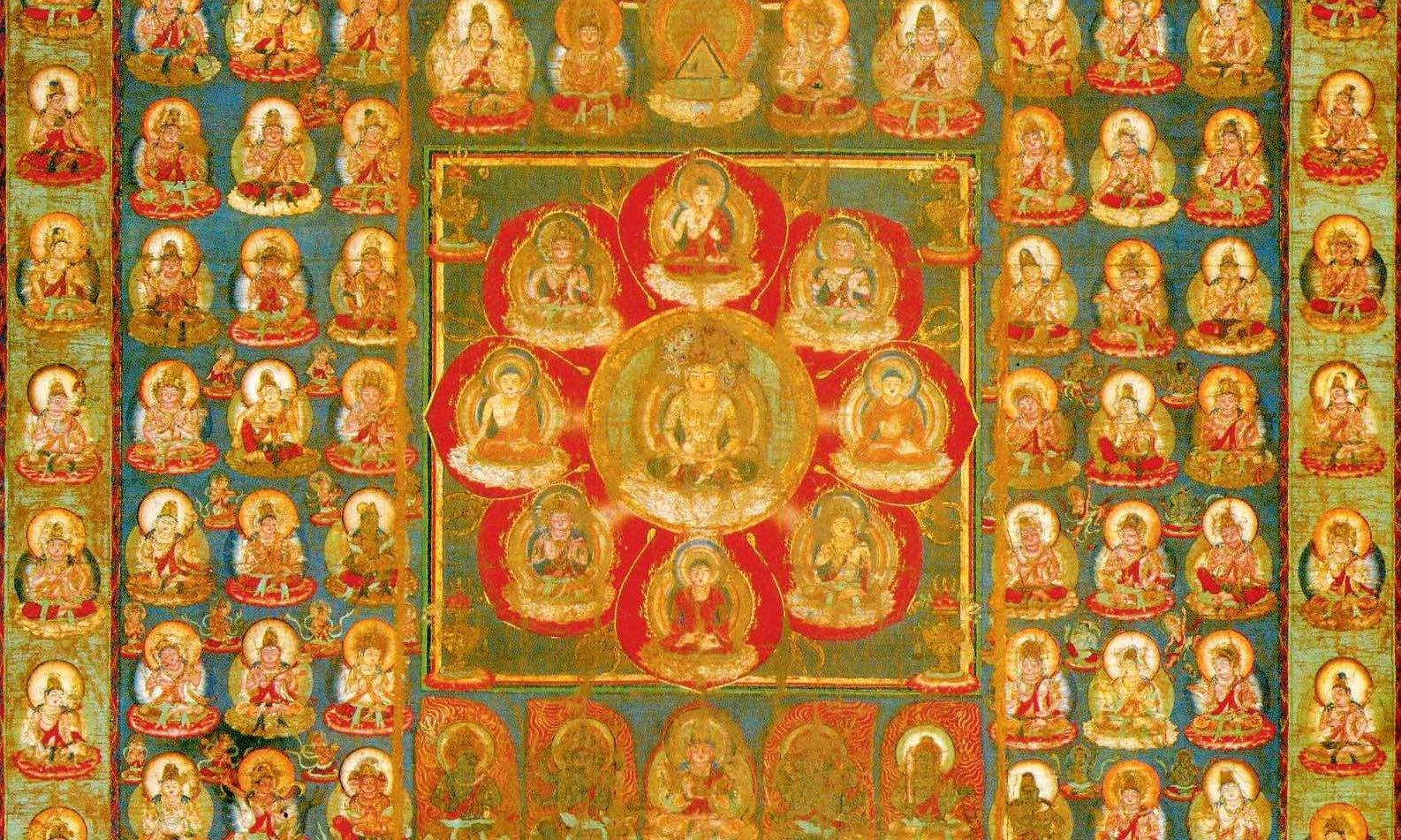

Buddhism

Beginning in the 6th century C.E., Buddhism arrived in Japan, after making its way from India via Central Asia, China, and Korea. As Buddhism was adopted and adapted to Japanese culture, it gradually influenced and altered existing Japanese beliefs and practices, including those about nature and the seasons. Buddhism was woven together with Shintō, leading to a dynamic process of cross-pollination referred to as Shinbutsu shūgō (the syncretism of Shintō and Buddhism).

Daibutsuden (Great Buddha Hall), Todai-ji, 743, rebuilt c. 1700, Nara, Japan (photo: CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The influence of Buddhism grew at Japan’s imperial court and spread throughout the country through imperial patronage, solidifying a bond between the religious and the secular.

When it was completed in the 740s, during the Nara period, the Buddhist temple of Tōdaiji epitomized the prominence of Buddhism as the largest building project to date in Japan. Beyond its expression of the new importance of Buddhism as a religion in Japan, the very way it was built relates to the deeply rooted importance of nature in Buddhist thought: built in wood, it was closely linked to the natural environment and to the longer history of wooden structures in Japan and among other Buddhist places.

Read essays about Buddhism in Japan

Tōdai-ji: When completed in the 740s, it was the largest wooden building project ever on Japanese soil and its creation reflects the complex intermingling of Buddhism and politics in early Japan.

Read Now >/2 Completed

Permanence and Impermanence

Since the 6th century, representations of the four seasons have often embodied the intersection of nature, Shintō, and Buddhism. The cycle of the four seasons expresses a sense of both permanence—as their cycle is seemingly endless, year after year—and impermanence—as each season waxes and wanes, giving way to the next. The coexistence of permanence and impermanence, so perfectly illustrated by the cycle of the seasons, connects both to the importance of nature in Shintō and to the ephemeral nature of life on Earth in Buddhist thought.

Kano Motonobu, Birds and Flowers of the Four Seasons, 16th century, pair of folding screens, ink, color, and gold on paper, 162.4 × 360.2 cm each (Hakutsuru Fine Art Museum, Kobe)

These notions were expressed and communicated in the arts, especially in poetry and painting, which were themselves often paired. In Japan, paintings depicting the seasons are known as shiki-e (literally, “painting of the four seasons”). The seasons were depicted in a wide range of mediums—from folding screens to handscrolls. Kano Motonobu’s folding screens, for example, include birds and flowers associated with each of the four seasons, and would have possibly sparked conversation about the cycle of time as they divided a room for a wealthy patron.

In the style of Kano Motonobu, this painting applies the fusion of Japanese and Chinese thematic and stylistic elements to the pictorial tradition of the four seasons. Birds and Flowers of the Four Seasons, late 16th century, one half of a pair of six-panel folding screens, ink, color, gold, and gold leaf on paper, 160.7 × 360.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Developments in the Heian period

In Japan, paintings depicting the seasons flourished during the Heian period (794–1185 C.E.)—an important period for literature and the arts. Later artists and poets would find inspiration in the arts and literature produced during the Heian period, as this chapter discusses below.

A scene from Azumaya, detail of a scroll showing The Tale of Genji, c. 1130, handscroll fragment (Tokugawa Museum, Nagoya, Japan)

During the Heian period, images nature, including of the four seasons, began to be called yamato-e, meaning “Japanese painting.” Yamato-e was understood as “Japanese” as opposed to “Chinese” or otherwise “foreign.” Yamato-e typically had bold colors and the use of gold leaf. Importantly, the pictorial tradition of the four seasons in Japan also allows us to see the fusion of Japanese and Chinese thematic and stylistic elements in painting over time. By the Nara period (710–794 C.E.), Tang-dynasty Chinese culture exerted a strong influence on Japanese culture, and the lavish Tang style was intertwined with Buddhist devotional art. Chinese models in art and literature heavily influenced Japan. Beginning in the 9th century, people in Japan began to desire something distinct, and, as a result, art and forms that were regarded as Japanese were clearly distinguished from those that were Chinese.

Yamato-e subject matter included landscapes, scenes from literary texts such as The Tale of Genji or The Tales of Ise, and people engaged in seasonal activities, events, and festivals. For example, in a fragment from a 12th-century handscroll depicting scenes from The Tale of Genji, we see a brightly colored scene of women in a Japanese imperial setting. They are surrounded by hanging and sliding panels that are adorned with scenes of natural features of Japan that are affected by the changing seasons, such as low hills and blossoming trees. The screens shown in the handscroll function as actual folding screens do: they divided space and helped to bring nature indoors.

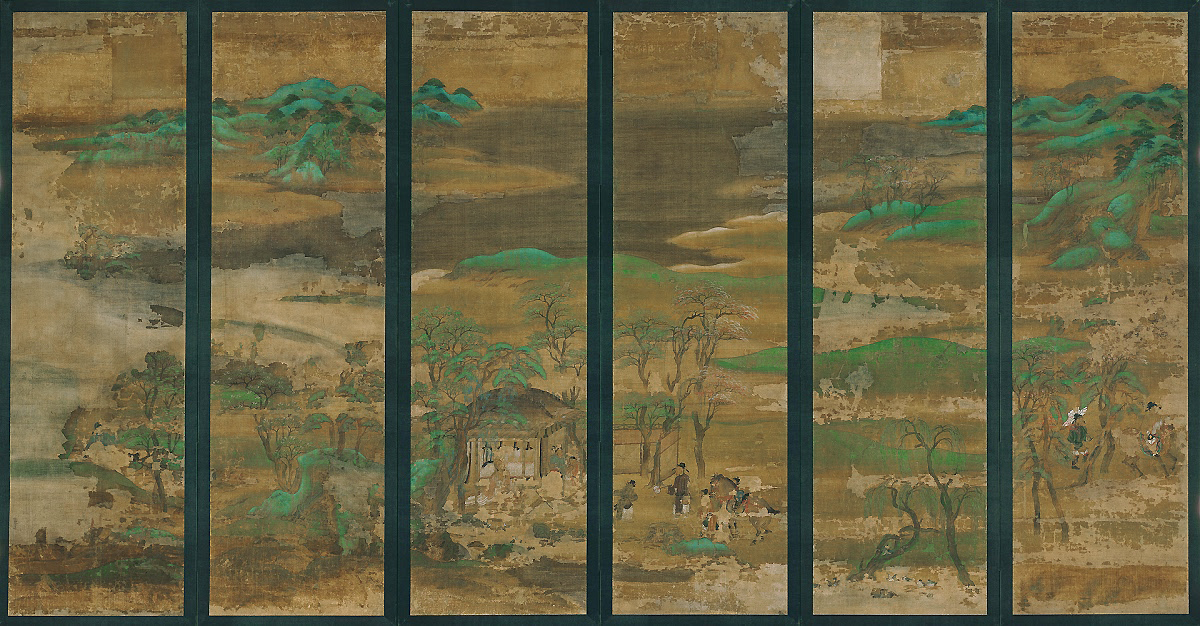

An example of kara-e. Senzui Byōbu (Landscape Screen), 11th century, ink and color on silk (Kyoto National Museum)

While the yamato-e paintings like the scene from the Tale of Genji draw on Japanese landscape elements, other artworks show the clear influence of Chinese landscape painting traditions. Kara-e, literally meaning “Tang painting,” is a term applied to paintings reflective of themes imported from China. First applied to Chinese Tang-dynasty (618–907 C.E.) paintings imported into Japan, kara-e came to characterize Japanese paintings modeled on Chinese paintings. Rather than look to what they saw around them, some Japanese artists depicted imagined landscapes of China as well as illustrations of Chinese tales and literary themes—such as we see in the Senzui Byōbu (Landscape Screen) above. It shows a Chinese poet living as a hermit in a landscape.

Left: An example of kara-e. Detail of Senzui Byōbu (Landscape Screen), 11th century, ink and color on silk (Kyoto National Museum); right: An example of blue-green landscape painting from China. Emperor Minghuang’s Journey to Shu, attributed to Li Zhaodao, Tang Dynasty (618–907), ink and color on silk, 55.9 x 81 cm (National Palace Museum, Taipei)

Kara-e also reflected an interpretation of Chinese painting techniques; the Senzui Byōbu, for instance, looks similar to Tang Dynasty blue-green landscape paintings that included bright mineral colors and fine-lined details. Still, the landscape itself looks Japanese, with low hills and flowering spring blossoms.

In the style of Kano Motonobu, this painting applies the fusion of Japanese and Chinese thematic and stylistic elements to the pictorial tradition of the four seasons. Paintings like Birds and Flowers of the Four Seasons also combine the painting of the four seasons with another prominent genre in Japanese art, the kachōga or bird-and-flower painting. Birds and Flowers of the Four Seasons, late 16th century, one half of a pair of six-panel folding screens, ink, color, gold, and gold leaf on paper, 160.7 × 360.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Over the centuries, paintings of the four seasons began to integrate both yamato-e and kara-e characteristics. In Birds and Flowers of the Four Seasons, a late 16th-century painting in the style of the artist Kano Motonobu, the yamato-e elements—bold colors and the use of gold leaf—are combined with kara-e elements—a dynamic composition featuring Chinese motifs such as pines and cranes.

Discussion Activity: Compare Birds and Flowers of the Four Seasons (shown earlier) to a representation of the four seasons by Tosa Mitsunobu, Kano Motonobu’s father-in-law, to identify different visual treatments of the four seasons.

Here: Tosa Mitsunobu (attribution), Bamboo in the Four Seasons, late 15th–early 16th century (Muromachi period), pair of six-panel screens; ink, color, gold leaf on paper, 157 × 360 cm each (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

In the arts of Japan, the contrast between concepts such as permanence and impermanence has been explored in other ways as well. For example, artists and sculptors have paired natural elements that are affected by the seasons, such as plants, with elements that are unchanging, such as rocks.

A blossoming tree, subject to seasonal changes, serves as backdrop to the seasonal arrangement of rocks and sand in the temple’s garden. Rock garden, Ryōanji, Kyoto, Japan (photo: Vincent Briccoli, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The dry landscape gardens found in Zen Buddhist monasteries are a fitting example. In the garden design of Zen Buddhist temples such as Ryōan-ji, vegetation subject to seasonal changes contrasts with the sand and rocks, impervious to seasonal changes. The dry rock garden is also a microcosm of nature—the rocks are like mountains, the gravel is water, and the moss and surrounding shrubs are the grass, trees, and flowers. The pairing of elements that change with those that do not was intended to encourage contemplation and meditation among Zen Buddhist monks.

Read an essay and watch a video about Ryōan-ji

Ryōan-ji (Peaceful Dragon Temple): The garden is the one of the most famous examples of a rock garden—a form which developed with the efflorescence of Zen Buddhism in medieval Japan.

Read Now >/1 Completed

Rituals and festivals of the seasons

Various festivals and rituals animated the activities and imagination of communities around Japan in response to the cycle of the seasons, the lunar and agrarian calendars, and Shintō beliefs. Evoked in poetry and drama and depicted in various forms of visual representation, these festivals and rituals have become major motifs in Japanese arts and culture, and are intimately linked to the seasons in which they take place.

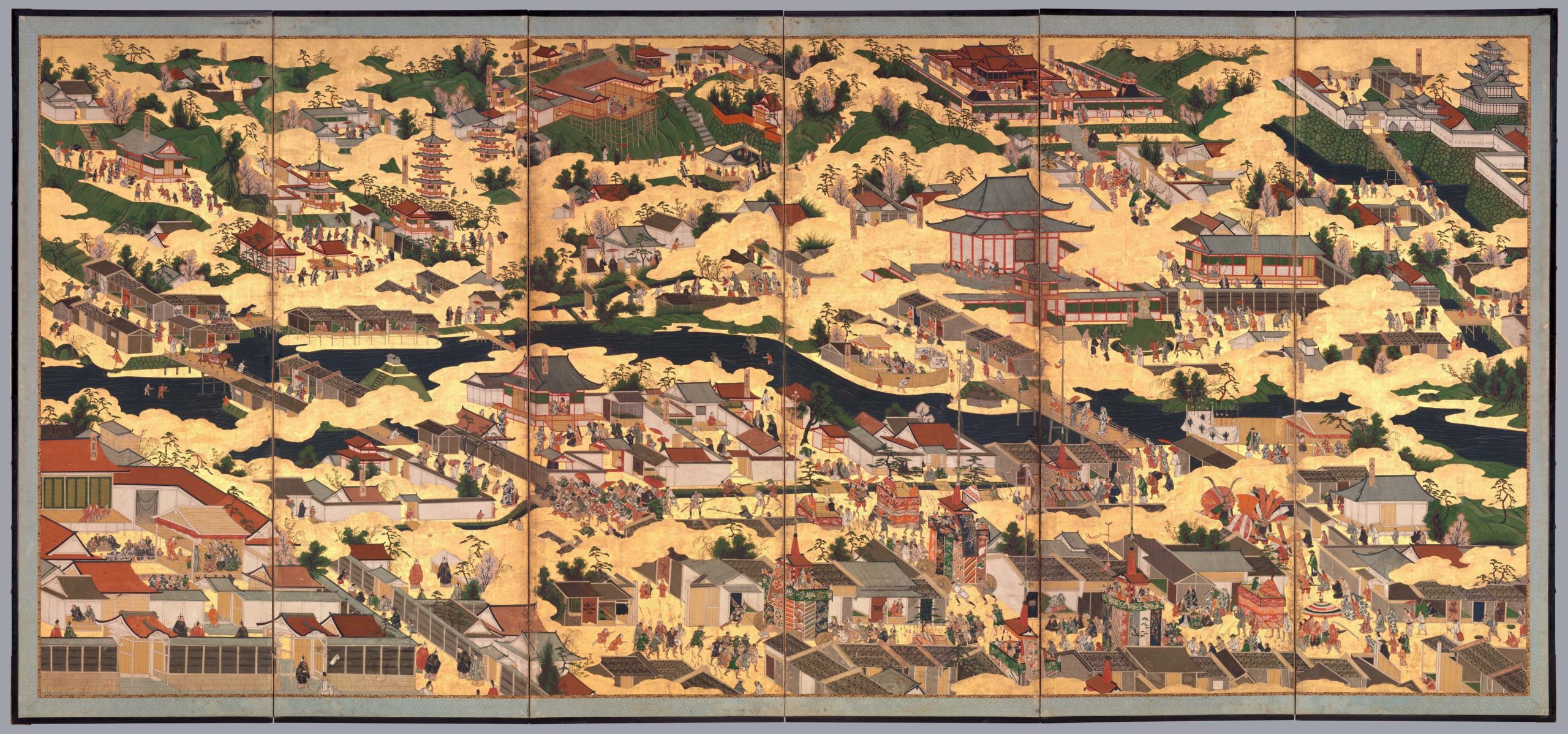

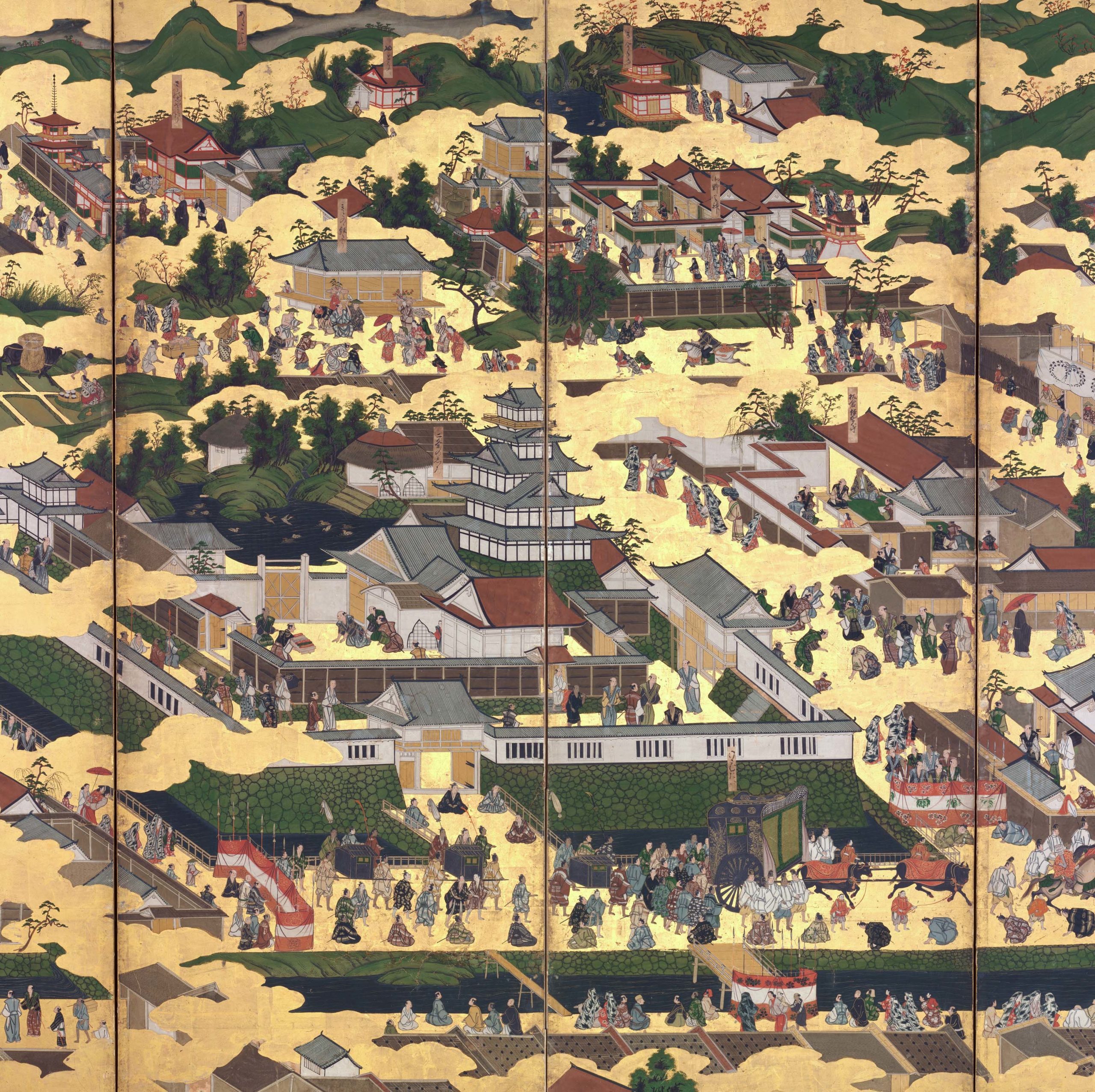

The four seasons inform this map-like depiction of Kyoto. Scenes in and around the Capital, 17th century (Edo period), right panel of a pair of six-panel folding screens; ink, color, gold, and gold leaf on paper, each: 156.1 × 352.2 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

A genre of painting known as rakuchū rakugai zu, literally “scenes in and around the capital,” depicts the former capital city of Kyoto in intricate compositions, typically on folding screens or sliding panels. It combines a high vantage point that lends the paintings a map-like structure with an extremely detailed, anecdotal rendition of buildings, people, and activities. Dating largely to the 16th through the 18th centuries, these paintings provide a valuable glimpse into how the seasons informed daily life.

A pair of screens from the 17th century, titled Scenes in and around the Capital, offer a panoramic view of the Kamo river and hundreds of people in an urban setting framed by hills and suburbs. Noticeable on the left screen is the Nijō castle, built in 1603 and the residence of Japan’s first shōgun, Tokugawa Ieyasu. The seasons add a temporal dimension to these paintings and are paired, according to ancient East Asian customs for auspicious site configurations, with the four cardinal directions: winter in the north, spring in the east, summer in the east, and autumn in the west. [1] On the far right of the screen, we see the summer Gion festival occurring in the streets.

Detail of left panel showing the Nijō Castle, Scenes in and around the Capital, 17th century (Edo period), one of a pair of six-panel folding screens; ink, color, gold, and gold leaf on paper, each: 156.1 x 352.2 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art). Scenes in and around the Capital also combines two subgenres: meisho-e (paintings of famous places) and tsukinami-e (paintings of seasonal events). It focuses on Kyoto (an element of meisho-e), and the detailed representation of season-specific events and activities (an element of tsukinami-e) are combined in a dynamic composition governed by the temporal logic and cultural significance of the four seasons.

Unlike other paintings focused more on the landscape’s transformation during the seasons, here the focus is on monuments that were the settings for seasonal events. Still, temporally, geographically, and culturally, the four seasons are an integral part of these paintings’ compositional structure, sense of movement, and detailed cross-section of life in the city.

The seasons as literary and cultural references

As genres continued to change and mature, certain combinations of places and seasons became increasingly popular in both literature and the visual arts (for example, the Gion festival in Kyoto in the summer or cherry blossom viewing at Mount Yoshino in the spring). Painters created a visual vocabulary that included references to poems, plays, and other literary works that evoked these places and seasons. The vocabulary was so frequently employed and well known for artists and their patrons that it became a codified system of cultural references, especially during the Edo period.

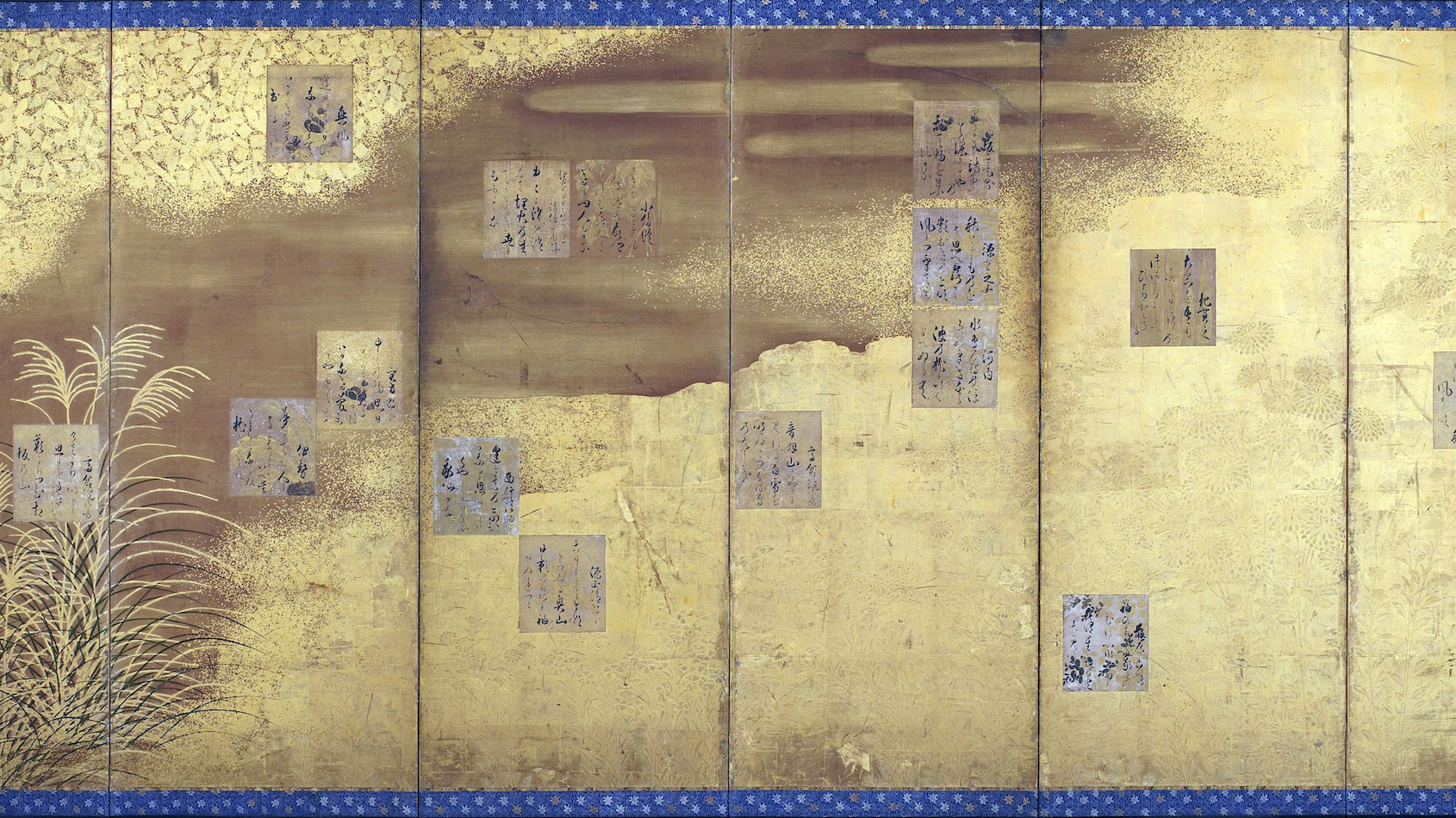

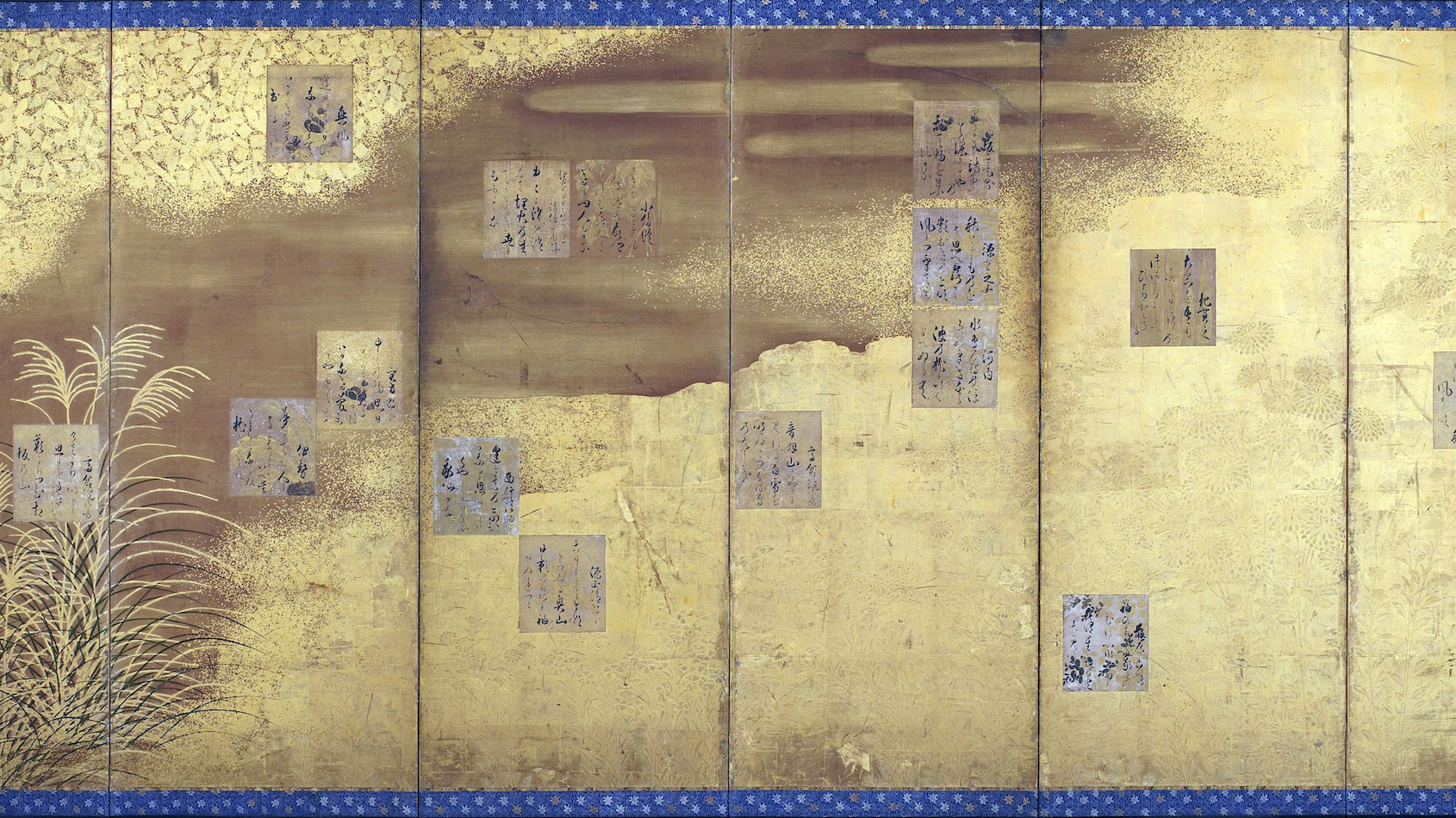

Hon’ami Kōetsu, folding screens mounted with poems from the anthology, Shin kokinshu, Edo period, c. 1624–37, ink, color, and gold on paper, Japan, 168.2 x 375.7 cm and 168.2 x 377.2 cm (Freer Gallery of Art)

During the Edo period, artists like Tawaraya Sōtatsu and Hon’ami Kōetsu depicted places and seasons by emulating the earlier Heian-period tradition of elegant lines, refined colors (such as the image from The Tale of Genji), and illustrations of Japanese tales and poems. They also infused the yamato-e style with a bold and elegant aesthetic, characterized by contrasting lines, shapes, and colors; diverse patterns arranged in rhythmic compositions; and delicately depicted natural elements paired with inscribed poetry, itself rendered in highly expressive calligraphic styles.

Detail, Hon’ami Kōetsu, folding screens mounted with poems from the anthology, Shin kokinshu, Edo period, c. 1624–37, ink, color, and gold on paper, Japan, 168.2 x 375.7 cm and 168.2 x 377.2 cm (Freer Gallery of Art)

In a folding screen with poems inscribed by Kōetsu, the seasons are depicted in two ways: through the flowers and grasses of the four seasons, such as spring peonies, and through the seasonal references embedded in the poems inscribed on the 36 cards embedded across the screens. The 36 poem cards evoke the tradition of the 36 immortal poets (venerated poets, past and present, who also focused on nature and the seasons) and other poetic and artistic series that include 36 elements, such as 36 views of Mount Fuji. Appreciating the meaning of the 36 poem cards and their referencing of the 36 immortal poets was only possible for those who knew of these cultural traditions and practices and were conversant in their myriad evocations.

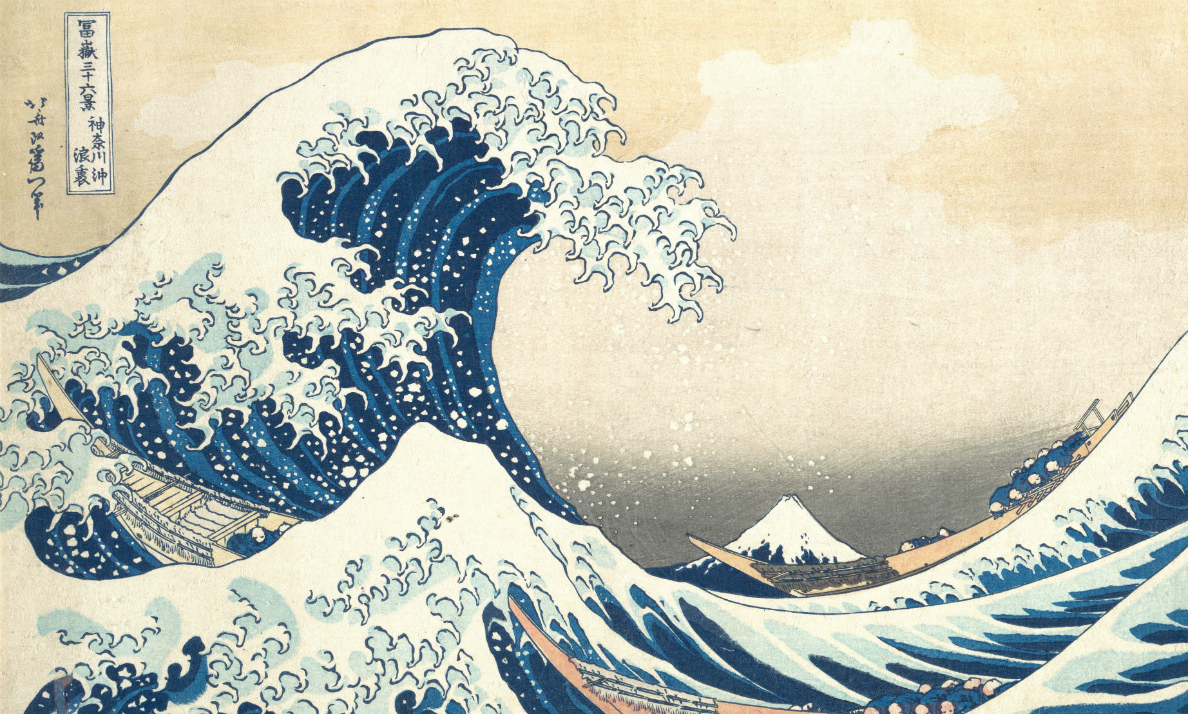

Katsushika Hokusai, Under the Wave off Kanagawa (Kanagawa oki nami ura), also known as The Great Wave, from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku sanjūrokkei), c. 1830–32, polychrome woodblock print, and ink and color on paper, 25.7 x 37.9 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

During the Edo period, it became common to develop print series that focus on one motif (such as a mountain) viewed in different seasons and under different weather conditions or times of day, and often paired with various human activities. For example, Katsushika Hokusai’s series of 36 views of Mount Fuji (produced between 1830 and 1832, with multiple impressions now in various museums and collections around the world), the visually and thematically unifying motif is Mount Fuji. Each image pairs the mountain with elements such as trees, waves, and boats to render it in the context of the four seasons and especially in relation to the human activities and events connected to the seasons. Hokusai’s Under the Wave off Kanagawa is part of his 36-view series depicting Mt. Fuji. Based on the garments that the figures in the boats are wearing, it most likely depicts Mt. Fuji in the spring. [2]

Ogata Kōrin, Red and White Plum Blossoms, Edo period, 18th century, pair of folding screens, color and gold leaf on paper, 156 x 172.2 cm each, National Treasure (MOA Museum in Atami, Japan)

Harkening back to the works of the artists Sōtatsu and Kōetsu, Ogata Kōrin’s Red and White Plum Blossoms exemplifies another way that Japanese artists began to focus on nature and the seasons. Assertive in both composition and color, the painting celebrates spring and exhibits the skill range of the artist. It is an example of the Rinpa style and demonstrates the ways in which an artist might focus on just one season.

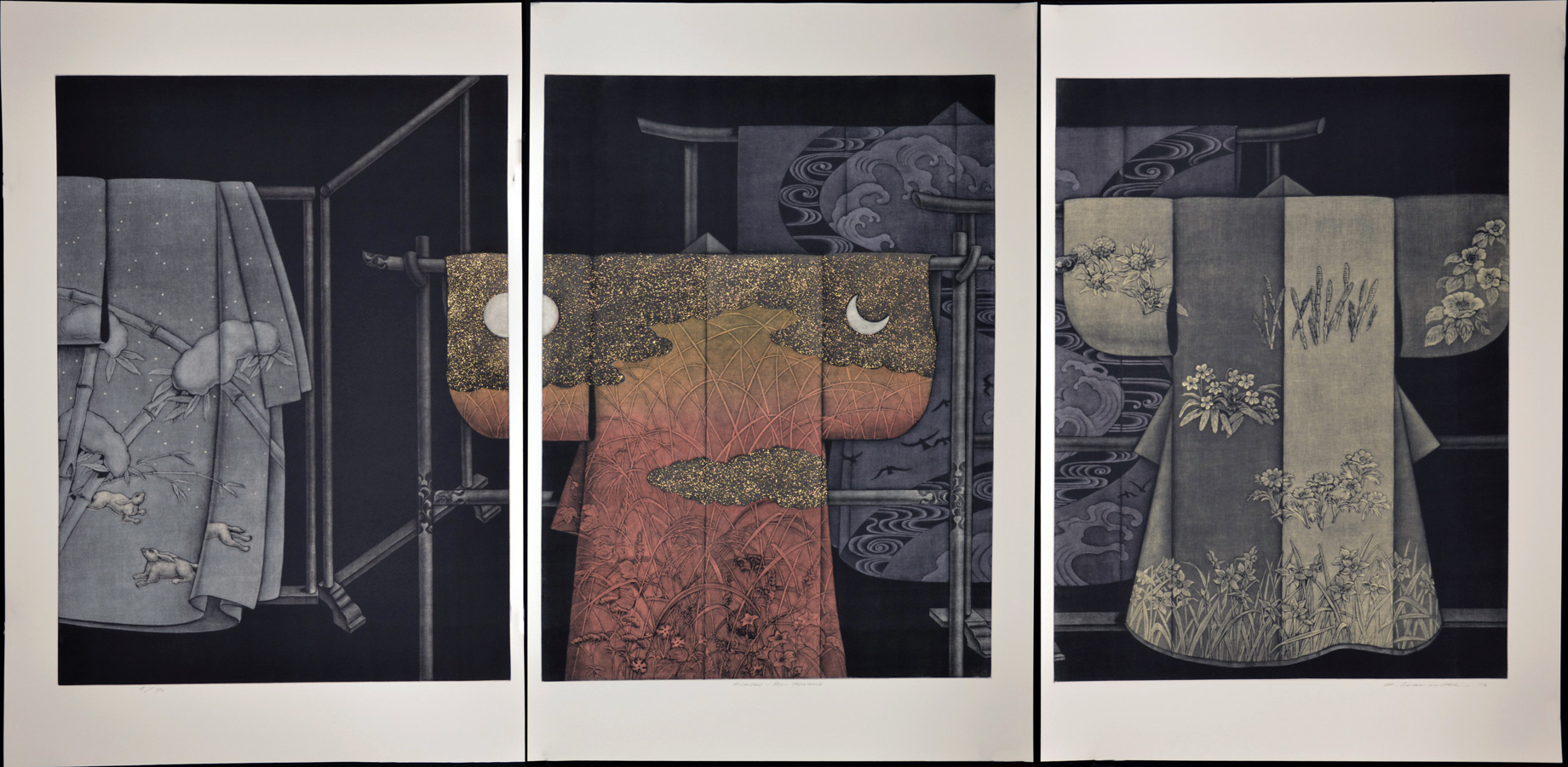

Hamanishi Katsunori, Kimono–Four Seasons, 2012 (Hesei period), triptych of mezzotint sheets, Japan, sheet (each): 75.2 x 53.3 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art) © Hamanishi Katsunori

Even today, references to the seasons remain a staple of artistic tradition in the arts of Japan. For example, in Kimono-Four Seasons (2012), Hamanishi Katsunori uses the mezzotint technique to depict the four seasons through classical pairings of natural elements embedded as decorative motifs on kimonos: winter (hares and snow-laden bamboo), spring (flowers), summer (birds flying over water), and autumn (grasses and the moon). Like Hamanishi, many contemporary artists evoke the four seasons in their works to establish a connection with, and to comment on, the central role of the seasons as markers of permanence, impermanence, spirituality, and classical Heian heritage in Japan’s cultural history.

Watch videos and read essays about the seasons as literary and cultural references

Hon’ami Kōetsu, Folding Screen mounted with poems: Two folding screens from Edo Japan show a lavish golden garden and 36 poem cards by the famous calligrapher Hon’ami Kōetsu.

Read Now >

Hokusai, Under the Wave off Kanagawa (The Great Wave): All of the images in the series feature a glimpse of the mountain, but as you can see from this example, Mount Fuji does not always dominate the frame.

Read Now >

Ogata Kōrin, Red and White Plum Blossoms: Combining metallic curls with mottled color, Kôrin’s screens capture the pulsing vitality of early spring.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Key questions to guide your reading

What role have nature and the four seasons played in the arts of Japan over the centuries?

What impact did Shintō and Buddhism have on representations of the four seasons in the arts of Japan?

What are the different genres and themes that feature season-specific elements?

Jump down to Terms to KnowWhat role have nature and the four seasons played in the arts of Japan over the centuries?

What impact did Shintō and Buddhism have on representations of the four seasons in the arts of Japan?

What are the different genres and themes that feature season-specific elements?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

Shintō

Buddhism

shiki-e

yamato-e

kara-e

dry rock garden

Rinpa style

Learn more

Julyan Cartwright and Hisami Nakamura, “What kind of a wave is Hokusai’s Great wave off Kanagawa?” in Notes & Records of the Royal Society 63, no. 2 (2009)

Matthew McKelway, Capitalscapes: Folding Screens and Political Imagination in Late Medieval Kyoto (United Kingdom: University of Hawai’i Press, 2006)

Seasonal Imagery in Japanese Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Haruo Shirane, Japan and the Culture of the Four Seasons: Nature, Literature, and the Arts (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012)