Heian period (794–1185 C.E.): Courtly refinement and poetic expression

During the Heian period, the new capital, Heian or Heian-kyō, was the city known today as Kyoto. There a lavish culture of refinement and poetic subtlety developed, and it would have a lasting influence on Japanese arts. The approximately four centuries that comprise the Heian period can be divided into three sub-periods, each of which contributed major stylistic developments to this culture of courtly refinement. The sub-periods are known as Jōgan, Fujiwara, and Insei.

The so-called Jōgan sub-period, spanning the reigns of two emperors during the second half of the 9th century, was rich in architectural and sculptural projects, largely spurred by the emergence and development of the two branches of Japanese esoteric Buddhism. Two Buddhist monks, Saichō and Kūkai (also known as Kobo Daishi), traveled to China on study missions and, upon their respective returns to Japan, went on to found the two Japanese schools of esoteric Buddhism: Tendai, established by Saichō, and Shingon, established by Kūkai.

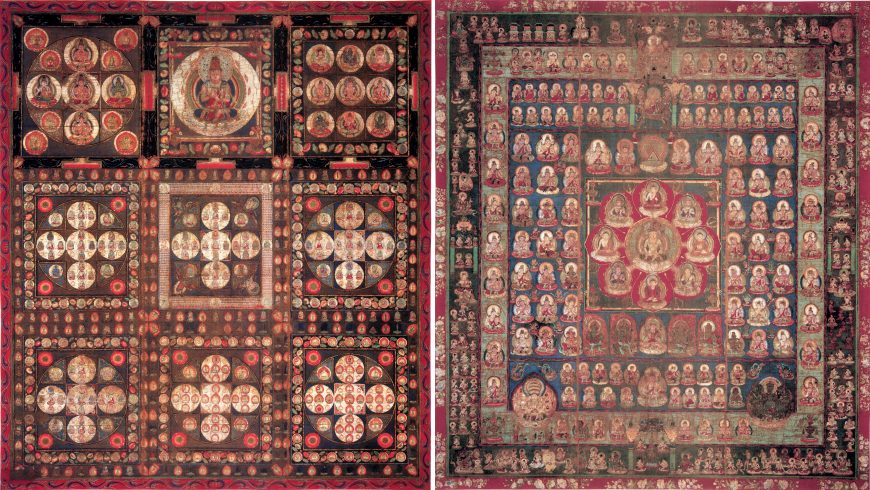

Ryōkai mandala 両界曼荼羅 (“the mandala of the two worlds”). Left: Kongōkai mandala 金剛界曼荼羅 (diamond realm mandala); right: Taizōkai mandala 胎蔵界曼荼羅 (womb realm mandala), 9th century, color on silk, 183 x 154 cm (Tōji, Kyoto, image: adapted from Wikimedia Commons)

In Esoteric Buddhist ritual, the Womb realm mandala is hung on the East wall, while the Diamond realm mandala is hung on the West wall. The mandalas face each other.

Among the many ideas and objects that they had brought back from China was the Mandala of the Two Worlds, a pair of mandalas that represent the central devotional image of Japan’s schools of esoteric Buddhism. Comprised of the “Womb World Mandala” (mandala of principle) and the “Diamond World Mandala” (mandala of wisdom), the Mandala of the Two Worlds was first assembled as a pair by Kūkai’s teacher in China. One such pair, still housed in Kūkai’s temple in Kyoto (Tōji, the “eastern temple”) represented a blueprint for countless mandalas made in Japan over the centuries.

It is believed that the consequential trip to China of Saichō and Kūkai was enabled by a member of the Fujiwara, the family that gives the name of one of the Heian sub-periods. The influence of the Fujiwara clan was paramount in the Japanese political and artistic world of the 9th and 10th centuries. Their power was bolstered by the ever-growing shōen system and ensured by their control of the imperial line, as Fujiwara daughters were married to imperial heirs.

Phoenix Hall/ Hōōdō 鳳凰堂 (Byōdō-in, Uji, Japan, image: Kansai Odyssey)

Phoenix statue on roof of Phoenix Hall, replaced in 1968 (image: Byōdō-in)

One of the only surviving structures from the Fujiwara period, the Phoenix Hall of the Byōdō-in (a Buddhist temple in Uji, outside Kyoto) is one of Japan’s most valuable cultural assets, with a fascinating, multi-layered story. The Phoenix Hall derives its name from the statues of phoenixes—auspicious mythological birds in East Asian cultures—on its roof.

Completed in 1053, the Phoenix Hall was sponsored by a member of the Fujiwara family—Fujiwara no Yorimichi—a pious believer in yet another type of Buddhism, known as Pure Land. This occurred at a time when many imperial villas like the Byōdō-in were converted into Buddhist temples. Having spread to Japan through the efforts of the monk Hōnen, the Pure Land School of Buddhism taught that enlightenment could be achieved by invoking the name of Amida, the Buddha of infinite light. Practitioners engage in the ritualistic invocation of Amida’s name—the nenbutsu 念仏—hoping to be reborn in Amida’s Pure Land, or the Western Paradise, where they can continue their journey towards enlightenment undisturbed.

Jōchō, Amida, 1053, gilded wood (Byōdō-in, Uji, Japan, image: Byōdō-in)

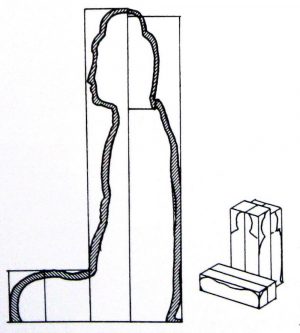

Yosegi-zukuri 寄木造 technique. Different parts of the sculpture are independently carved from multiple wood blocks, then joined (image adapted from: kanagawa-bunkaken)

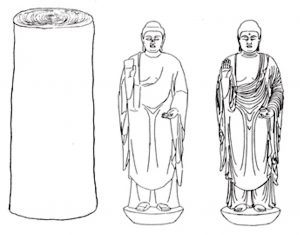

Ichiboku-zukuri 一本造 technique. Left to right: block of wood; sculpture carved in rough form out of the wood block; fine details are further carved (image adapted from: Nara National Museum)

The Amida sculpture in the Phoenix Hall at Byōdō-in is the only work still extant by Jōchō, an influential sculptor who was awarded remarkable distinctions, worked on various commissions from the Fujiwara family, and organized fellow sculptors into a guild. Jōchō’s Amida at Byōdō-in reflects the sculptor’s yosegi-zukuri 寄木造 technique, in which the sculpture is formed from multiple joined pieces of wood. This technique was different from the ichiboku-zukuri 一本造 technique, according to which the sculpture is carved out of a single block of wood.

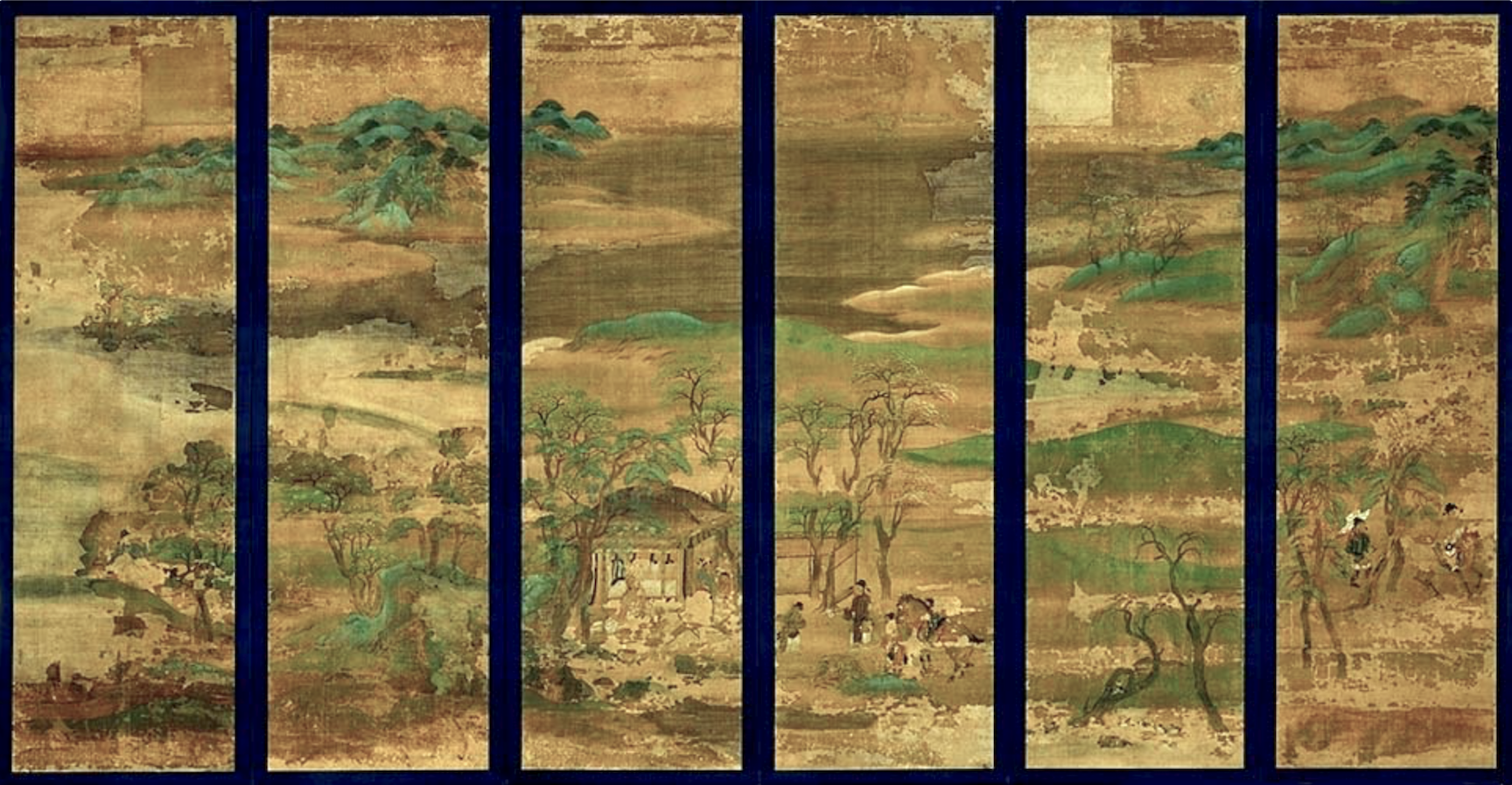

During the Heian period, the style known as yamato-e (大和絵 or 倭絵) is born. Understood as “Japanese” as opposed to “Chinese” or otherwise “foreign,” yamato-e encompasses a wide range of technical and formal characteristics but refers to specific formats—folding screens (byōbu 屏風) and room partitions (shōji 障子)—and specific choices of subject matter—landscapes with recognizably Japanese features and illustrations of Japanese poetry, history, mythology, and folklore.

One of the earliest examples of Heian-period yamato-e landscape painting. Senzui byōbu 山水屏風 (lit. “folding screen(s) with (imagery of) mountains and waters), six-fold screen, 11th century, color on silk, 146.4 x 42.7 cm, designated National Treasure (Kyoto National Museum)

Detached segment of illustrated scroll of the Tale of Genji, 12th century, opaque colors on paper (Tokyo National Museum)

A favorite subject for late-Heian-period yamato-e was the Tale of Genji (Genji monogatari 源氏物語), written in the first years of the 11th century and attributed to a lady-in-waiting at the imperial court, Murasaki Shikibu. A complex novel that focuses on the romantic interests and entanglements of the prince Genji and his entourage, the Tale also provides a fascinating entryway into Heian-period court life, complete with the aesthetic principles and practices that resided at its core.

The earliest illustrations of the Tale came in handscroll format. Surviving fragments exemplify the yamato-e mode of narrative painting: illustrations by episode interspersed with passages of text; roofless buildings, multiple viewpoints (typically both frontal and from above), and schematic renditions of faces ( hikime kagihana 引目鈎鼻, literally translated as “drawn-line eyes, hook-shaped nose.”)

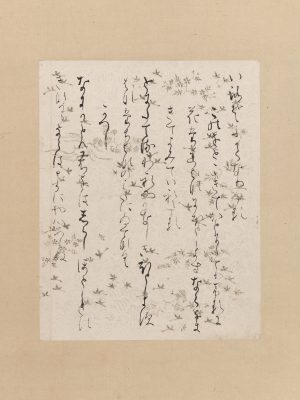

“Lady Ise Collection”, poetry calligraphy, early 12th century, book page mounted as hanging scroll, ink on decorated paper (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

A brief review of the Heian period cannot be complete without mention of the development of Japanese poetry, waka in particular. Waka was an integral part of the Tale of Genji, and Murasaki Shikibu came to be known as one of the 6 immortal poets (all of whom were from the Heian period).

Permeating the spirit of Heian-period Japanese poetry and the imagery it inspired was a heightened sense of refinement, expressed in elegant verse, stylized visual motifs, precious materials, and embellished surfaces.

The Insei rule—the third and last of the Heian sub-periods —refers, literally, to the imperial practice of ruling from within a (monastery) compound. During Insei, cloistered emperors had a higher degree of political control. It was during this period that a sense of aesthetic and ethical congruence developed, according to which the beautiful and the good are intrinsically interconnected.

Additional resources:

For information on other periods in the arts of Japan, see the longer introductory essays here:

A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Jomon to Heian periods

A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Kamakura to Azuchi-Momoyama periods

A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Edo period

A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Meiji to Reiwa periods

JAANUS, an online dictionary of terms of Japanese arts and architecture

e-Museum, database of artifacts designated in Japan as national treasures and important cultural properties

On Japan in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Richard Bowring, Peter Kornicki, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Japan (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993)