[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:05] We’ve made our way up the steep hillside on the north end of Kyoto, and we’ve entered into the temple complex of Ryōan-ji.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:13] When we entered the temple, we were asked to take off our shoes. We’re in a spiritual space, but also one that tourists are making their way through. The complex consists of many temples, and shrines, and places of meditation for the monks who lived here.

[0:30] This is specifically a place related to Zen Buddhism. The most famous place within is the rock garden, and that’s where we’re standing now.

Dr. Zucker: [0:39] You can see the garden as a distillation of the ideas of Zen Buddhism, and of the highly refined sense of Japanese aesthetics. This is such a refined space. We see an enclosed courtyard filled with light-gray stones, with a series of moss islands from which rocks protrude.

Dr. Harris: [0:57] When we think of a garden, we think of flowers. We might think of a water feature, the informality of an English garden, the rigid geometry of a French garden, but a Zen garden is to encourage meditation. In fact, the word “zen” means “meditation.”

Dr. Zucker: [1:14] The central idea of Buddhism is cultivating oneself, of reaching enlightenment. A garden is an attempt to cultivate nature, to bring out its essential qualities.

Dr. Harris: [1:25] For Buddha, the world was a place of suffering, and desire was the cause of suffering. The goal is to transcend that suffering, to transcend the cycle of rebirth, of samsara. In Zen Buddhism, the path is sudden enlightenment that comes through meditation.

Dr. Zucker: [1:42] Nature is looked at carefully: its innate qualities, its imperfection, its inherent forms, and that becomes the starting point. The idea is not to erase nature and make something that’s perfect. The idea is to examine something, to understand its qualities, and then to enhance them.

Dr. Harris: [2:00] Finding beauty in what is worn, what is aged. When we look around the edges of the rock garden of this enclosure, we see a wall that hasn’t been recently painted, it’s worn.

Dr. Zucker: [2:12] That creates this atmospheric quality that makes the entire garden reminiscent of a Japanese painting, where the rocks function as mountains, and the two-dimensional wall functions as an atmospheric space.

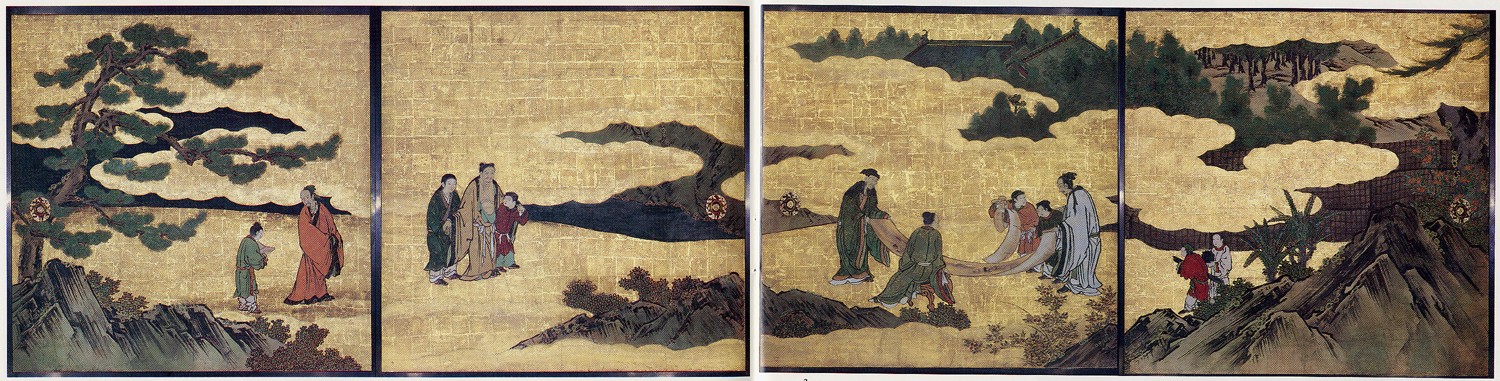

[2:25] In the study area for the abbot that is just adjacent to the garden, there are paintings that show rocky crags emerging out of a sea of mist. It’s a perfect reflection of the garden itself.

Dr. Harris: [2:35] It’s more beautiful in a Japanese aesthetic to not see a perfect view of the mountain on a perfectly clear day, but rather for the mountain to be obscured by the mist. There’s an opening for interpretation, for the suggestive, for…

Dr. Zucker: [2:52] Surprise.

Dr. Harris: [2:53] …for things that are half there, half hidden. And as we move through the garden, our view shifts, the numbers of rocks that we see shift. That idea of never seeing the whole, but the appreciation for the incomplete, is here.

Dr. Zucker: [3:08] The pebbles have been raked into a very deliberate pattern, one that emphasizes the horizontal. It slows our eyes down. Ovoid shapes frame each of the individual islands, the waves of the sea.

Dr. Harris: [3:20] The analogy of water. It also suggests to me, in its sparseness, when the stuff of the world came to being out of nothingness.

Dr. Zucker: [3:30] This is a garden that’s meant to incite enlightenment that could come to you at any moment. That, even on this cloudy, slightly rainy day, the garden is bright and feels dry.

[3:40] But just immediately to its right is a densely forested rectangle, slightly smaller than the rock garden. It is completely carpeted with green moss, and it’s such a relief for the eye.

Dr. Harris: [3:53] This is all about our eye, awakening our eyes, asking us to look, asking us to pay attention. The very act of paying attention takes us out of our everyday lives and takes us to a place of heightened awareness, of standing apart from things. And in that way, helping to prepare the path for enlightenment.

[4:16] [music]

Gate, Ryōanji (Peaceful Dragon Temple), Kyoto, Japan (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Ryōanji thrived as a great Zen center for the cultural activities of the elite from the late sixteenth through the first half of the seventeenth century under the patronage of the Hosokawa family. When visitors pass through the main gate, they encounter the Mirror Pond (Kyōyōchi) on the left with a scenic view of surrounding mountains.

Dry rock garden, study and grounds, Ryōanji (Peaceful Dragon Temple), Kyoto, Japan (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Dry Landscape Garden (karesansui) in Ryōanji

Muqi Fachang, Returning sails off a distant shore (from Eight Views of the Xiao and Xiang Rivers), 13th century, handscroll cut and remounted as eight hanging scrolls, ink on paper, 103.6 x 32.3 cm (Kyoto National Museum)

The garden may have been inspired by aspects of both Japanese and Chinese culture. For instance, Shinto, an indigenous religion of Japan, focuses on the worship of deities in nature. Also, Zen Buddhism, which is derived from Chan Buddhism in China, emphasizes meditation as a path toward enlightenment. Medieval Chinese landscape paintings associated with this sect of Buddhism often displayed a sparse, monochromatic style that reflected a spontaneous approach to enlightenment. Together, these concepts promoted the aesthetic values of rustic simplicity, spontaneity, and truth to materials that came to characterize Zen art. Today, the sea of gravel, rocks, and moss of the rock garden and the earthy tones of the clay walls contrast with the blossoming foliage beyond—evoking stillness and contemplation suitable for meditation.

Dry rock garden, Ryōanji (Peaceful Dragon Temple), Kyoto, Japan (image: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

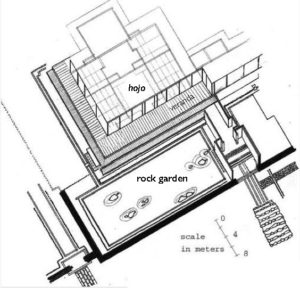

Like other Japanese rock gardens, the Ryōanji garden presents stones surrounded by raked white gravel with minimal use of plants. Fifteen rocks of different sizes are carefully arranged in groups amidst the raked pebbles covering a 250-square-meter rectangle of ground. The stones are carefully arranged so that one can only see no more than fourteen of the fifteen at once from any angle. Staring from the largest group on the far left, a visitor’s eyes rhythmically move through the garden from the front to the rear and back, and then from the front to the right upper corner.

Hōjō, Ryōanji (Peaceful Dragon Temple), Kyoto, Japan (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Date? Creator?

Ryōanji (Peaceful Dragon Temple), dry rock garden, study and grounds, Kyoto, Japan (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The meaning of the garden

Kyōyōchi (Mirror-Shaped Pond), Ryōanji (Peaceful Dragon Temple), Kyoto, Japan (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Art and architecture in Ryōanji

Appreciation of Painting, from a set of the “Four Accomplishments,” Kano school, Momoyama period, c. 1606, four of eight panels mounted on sliding-door panels, ink, color, gold and gold leaf on paper, 182.9 × 731.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Ryōanji and Zen culture in the modern era

Recent scholars criticize the romanticized notion of Zen art and culture as a symbol of Japanese aesthetic—pointing out that this interpretation is largely a product of the twentieth century, fueled by growing nationalism in Japan. Furthermore, Zen Buddhism was disseminated in the West and filtered through modernist artists, who were fascinated by the minimalistic perspectives and abstracted forms of Japanese rock gardens. Whatever the skepticism one reserves for existing assumptions about the Zen garden and culture, no one can deny the cultural and historical significance of Ryōanji and its rock garden.